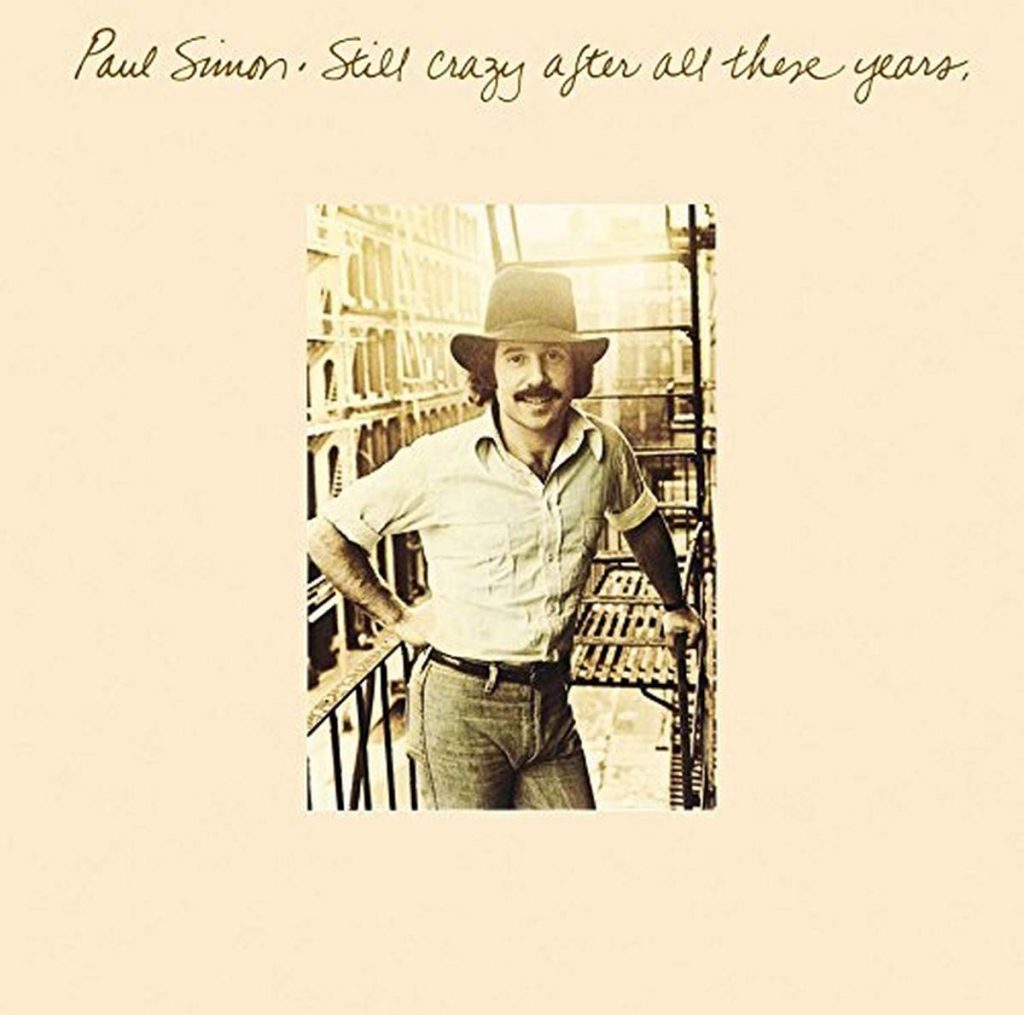

On his third solo album after parting ways with Art Garfunkel, Paul Simon further distanced his songcraft from the folk-rock framework the pair had established. Simon had already explored elements of rock, gospel and world music, but with Still Crazy After All These Years he pursued a broader synthesis that heightened additional pre-rock American pop and jazz elements. Released in mid-October 1975, the set was more sophisticated yet also more emotionally candid than previous work, warmed by self-effacing humor.

On his third solo album after parting ways with Art Garfunkel, Paul Simon further distanced his songcraft from the folk-rock framework the pair had established. Simon had already explored elements of rock, gospel and world music, but with Still Crazy After All These Years he pursued a broader synthesis that heightened additional pre-rock American pop and jazz elements. Released in mid-October 1975, the set was more sophisticated yet also more emotionally candid than previous work, warmed by self-effacing humor.

Beneath that polished craftsmanship, Simon transmuted personal sorrow into the most elegant and richly detailed music he had made up to that point. Despite a mantel full of Grammys and platinum awards garnered with Simon and Garfunkel and his post-duo sets, he was struggling with depression detected as his first marriage foundered. Years later, he would trace the album’s title song to a broken moment when he felt overwhelmed by sadness, summarized by Robert Hilburn in his 2018 biography of Simon: “How, after all his success, could he feel so bad? Suddenly, a phrase came to him that would summarize his feelings. Ironically, the phrase, born in sorrow, would be the title of a song [and album] embraced by millions as an upbeat expression of survival.”

Where Simon’s previous album, 1973’s Grammy-winning There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, had kicked off with a spry acoustic guitar motif for the energetic nostalgia of “Kodachrome,” its successor opened with a pensive keyboard figure played by Barry Beckett on Fender Rhodes, setting up Simon’s reflection on a chance encounter with an ex-lover the night before. Against a gentle waltz cadence, he recounts the conversation, a few beers, then a casual parting before concluding he’s “still crazy after all these years.” The title phrase and a second self-effacing verse convey an aural shrug, only to pivot as Bob James’ spacious orchestration swells toward a new key for a striking bridge betraying deeper feelings:

“Four in the morning

Crapped out

Yawning

Longing my life away

I’ll never worry

Why should I

It’s all gonna fade…”

A flurry of strings and staccato flutes follows before a second modulation as Michael Brecker’s soaring tenor saxophone wordlessly projects unresolved yearning. The arrangement’s strategic key changes and classic pop palette of keyboard, reeds and strings measure just how much he had expanded his musical horizons beyond the basic guitar vocabulary of his earlier recordings. Classical guitar lessons followed by tutelage in jazz harmonies with double bassist Chuck Israels and vocal technique with David Soren Collyer had carried Simon’s music further beyond earlier folk and Brill Building pop, enabling him to create an evergreen that warranted comparison with the “great American songbook” of mid-20th century songwriters.

Watch Paul Simon perform the title track live in NYC’s Central Park in 1991

His enhanced harmonic toolkit informs a more intimate small ensemble setting for another meditation on failed relationships, “I Do It for Your Love,” a lambent reflection on a marriage and its demise that reaches the sad, concise conclusion that “love emerges, and it disappears.” A languid Brazilian influence becomes explicit with the accordion and falsetto vocalese of guest Sivuca, anticipating Simon’s deeper immersion into Brazilian music on The Rhythm of the Saints 15 years later.

Co-producer Phil Ramone, to whom he had turned for Rhymin’ Simon, proved an ideal ally to nurture Simon’s involvement with New York’s first-call jazz and studio musicians, several of whom would become fixtures of Simon’s touring bands. Also returning were the members of the Muscle Shoals rhythm section, including Beckett, bassist David Hood, drummer Roger Hawkins and guitarist Pete Carr, who had buoyed key tracks on Rhymin’ Simon.

The New York cohort aces what became the album’s biggest single and Simon’s only #1 chart hit, “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” propelled by drummer Steve Gadd’s minimalist, martial riff on snare and cymbal, accenting Simon’s sly pillow talk with a new romantic partner. The song’s playful rhyming scheme baits its hooks with backing vocals from Phoebe Snow, Patti Austin and Valerie Simpson. Simon ascribed the rhyming gambit to a game played with his son, Harper, but it’s tempting to hear Simon’s “50 Ways…” as an inversion of Chicago blues and R&B muse Willie Dixon’s bawdy, bragging 1953 single, “29 Ways,” despite little evidence that a pubescent Simon ever heard Dixon’s track back in Queens.

Snow earns a vocal spotlight on another single candidate, “Gone at Last,” which revisits the gospel fervor that had powered “Loves Me Like a Rock” on the previous album. Simon and Ramone first envisioned a Latin-tinged duet with Bette Midler before recasting the arrangement for Snow to trade lissome vocals with Simon against the call-and-response of the Jessy Dixon Singers.

Simon’s success sustained him in the front rank of the singer-songwriters that had emerged as key figures in ’70s pop and rock, yet his legacy in Simon and Garfunkel still cast a long shadow with its run of multi-platinum hit albums, cresting with Bridge Over Troubled Water, which racked up 25 million albums sold globally, and a greatest hits package that would reach platinum 14 times over. While tensions remained following their break, Simon offered him a new song for Garfunkel’s second solo album, suggesting material already gathered for the set was too soft.

Garfunkel loved the melody but was reportedly taken aback by the dark lyrics to what became “My Little Town,” a bitter travelogue through a blighted suburb capped by the remorseless chorus, “Nothing but the dead and dying back in my little town.” For his part, Simon claimed the goal was to provide something “nasty” enough to add edge, insisting, “It’s not the story of our little town, Kew Garden Hills,” the Queens neighborhood where they had first met.

Columbia Records was predictably elated at the prospect of a new Simon and Garfunkel song and inevitably hoped it was a precursor to a formal reunion after Garfunkel graciously agree to share the track, which would appear on both albums. “My Little Town” would reach #1 on Billboard’s Adult Contemporary chart and peak at #9 on the Hot 100, but the old grievances that had divided the two men would never fully resolve, limiting reunions to their historic 1981 Central Park concert and 2003’s “Old Friends” reunion tour.

Related: Our Album Rewind of There Goes Rhymin’ Simon

Still Crazy After All These Years, meanwhile, would prove to be the only Paul Simon solo album to reach #1 in the Billboard album chart, although failing to reach the platinum rung attained by his previous album. Nonetheless, Simon’s ongoing track record with the Recording Academy was sustained by Grammys for Album of the Year and Best Male Pop Vocal Performance.

Watch Simon & Garfunkel perform My Little Town” live during their 2003 “Old Friends” tour

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

1 Comment

Simon on SNL doing “Still Crazy…” is classic.