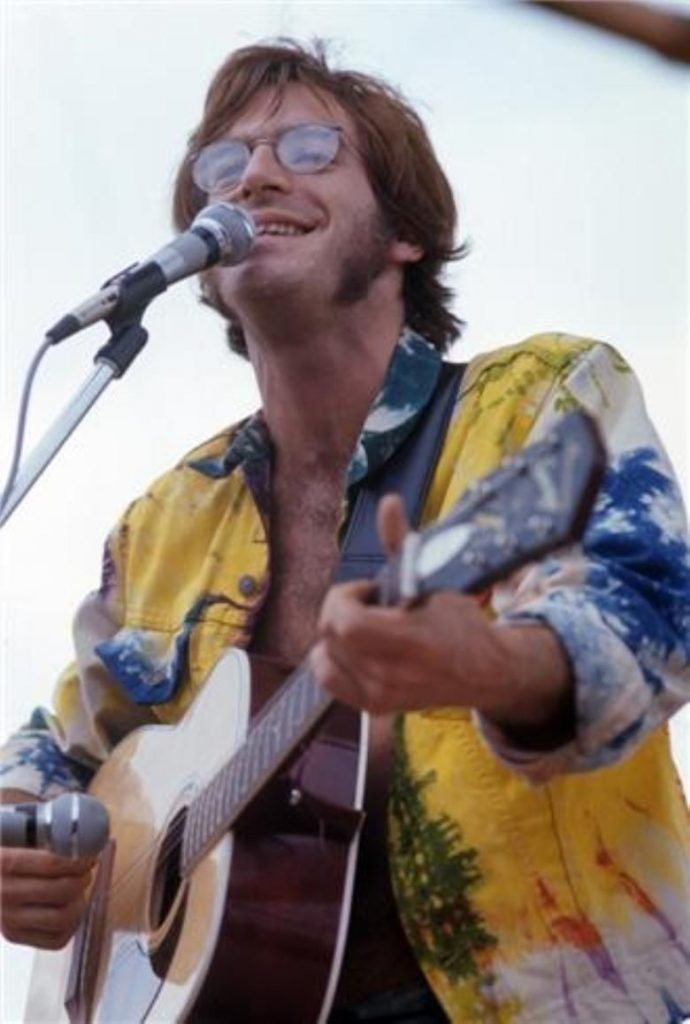

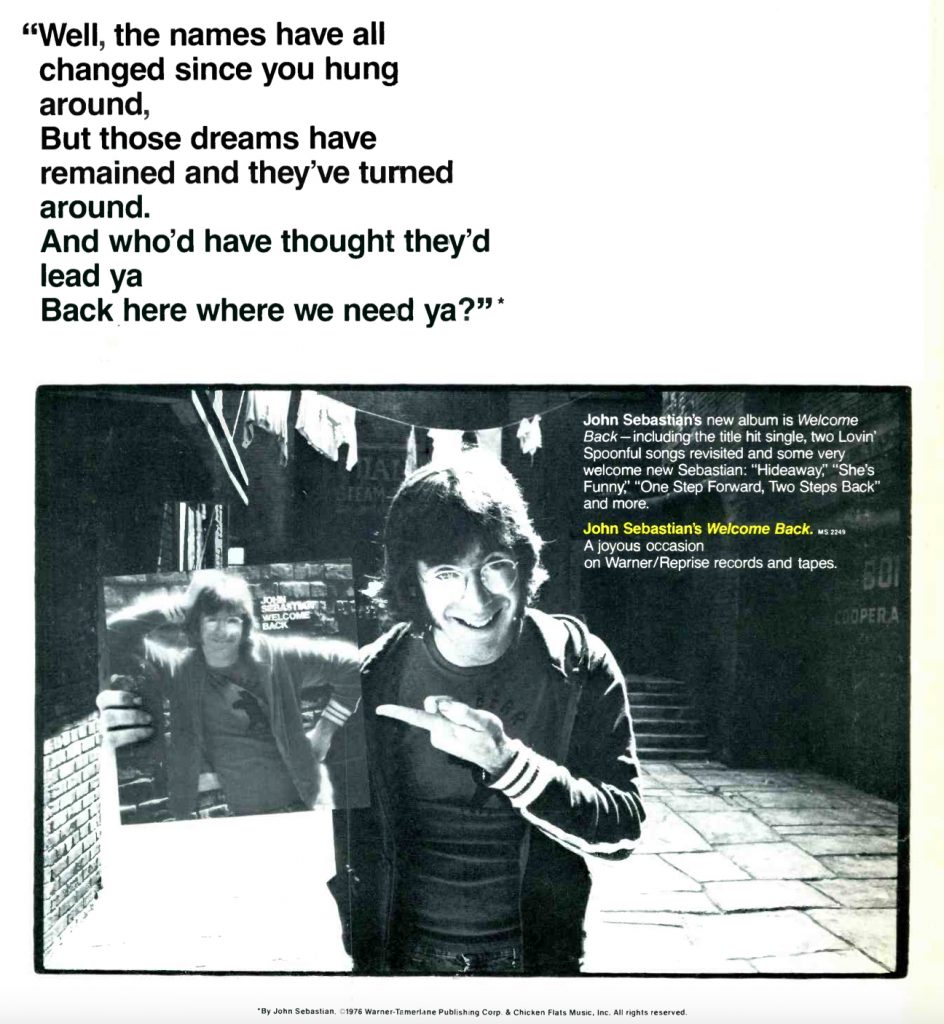

[This interview first appeared on Best Classic Bands in December 2021.] Although John Sebastian has always included songs from his time with The Lovin’ Spoonful in his solo sets—he even played two of the band’s tunes at Woodstock in 1969—for the most part he has resisted re-recording them. The former lead singer and chief songwriter of the Spoonful—Sebastian on guitar, harmonica, autoharp and vocals; Zal Yanovsky on lead guitar; Steve Boone on bass and Joe Butler on drums—has always felt that those original versions were definitive and didn’t need to be revisited on record.

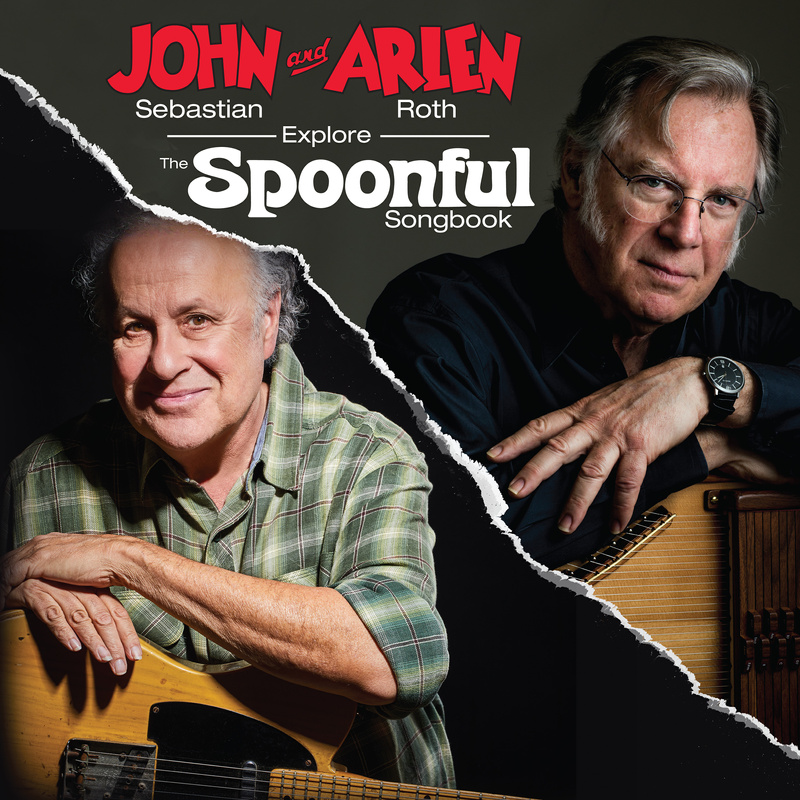

That all changed in 2021 with the release of John Sebastian and Arlen Roth Explore the Spoonful Songbook, featuring Sebastian and guitarist extraordinaire Roth rearranging 13 of the best known Spoonful tunes along with one (“Stories We Could Tell”) from the singer-songwriter’s post-Spoonful solo career. The album includes both vocal renditions—some featuring Sebastian alone and others with guest vocalists Geoff and Maria Muldaur, the MonaLisa Twins and Lexie Roth (daughter of Arlen)—and a handful of instrumental renditions. Both major Spoonful hits—“Do You Believe in Magic,” “Daydream,” “Nashville Cats,” “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?,” etc.—and deeper album cuts are newly interpreted on the album to stunning effect. Sebastian and Roth are joined on the recording by bassist Ira Coleman and drummer Eric Parker, with John’s son Benson Sebastian supplying percussion.

Sebastian—who wrote and sang all of the band’s hits from its inception in 1965 until he left in the spring of ’68—and Roth have known each other for some 35 years and their interaction on these classic songs is natural and inspired. The music is instantly familiar while simultaneously sounding fresh. In a 2021 phone chat, Sebastian, born March 17, 1944, spoke with Best Classic Bands about the making of Explore the Spoonful Songbook as well as the background of several of the tunes on the album, and key events in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame-inducted Lovin’ Spoonful’s career.

Best Classic Bands: In the liner notes for your new album, you say that it was Arlen Roth’s idea to redo songs from the Spoonful catalog. Did he have to convince you, or were you receptive to that suggestion?

John Sebastian: I had, in all previous situations, avoided trying to recapture the magic of one or another of those big hits. But our friendship was based around sitting around playing for no purpose at all. I did at first kind of go, “God, how would we do that?” Because I am very aware of how badly you could bomb being 77 and trying to do the stuff you did when you were 20. It is kinda goofy. But really, the allure was that Arlen and I do have certain instincts together as a result of being accompanists, as well as the guy under the spotlight. That was a real advantage. As soon as we started playing the tunes, I realized how thoroughly Arlen had taken in Zal Yanovsky. That was kind of a surprise. He’d play a lick and I’d go, “Is that his?” And he’d say, “Yes, John, that is.”

Zal’s style was so wide-ranging that it has to be a lot of work to assimilate all of that.

Arlen says that what Zal had going was this combination of a bluesy approach and a country approach. It’s almost pianistic.

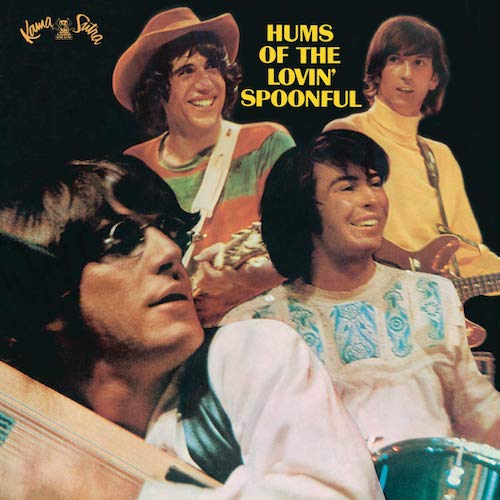

If you listen to some of the tunes on the Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful album, for example “Coconut Grove,” “Nashville Cats” and “4 Eyes,” which run consecutively, it doesn’t even sound like the same guy playing guitar from tune to tune.

That is the biggest victory, always, for me. In our era, there was the idea of when that new single comes out, we don’t want anybody to know who it is. But the weird thing was, immediately, the DJ would say, “Here they are with that great Spoonful sound.” We’re mashing our foreheads going, “Come on!”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful

Even the difference between the biggest singles—“Do You Believe in Magic,” “Daydream” and “Summer in the City”—is so vast.

Even the difference between the biggest singles—“Do You Believe in Magic,” “Daydream” and “Summer in the City”—is so vast.

And it was a moment when following up was so much a part of pop music that everybody had something that sounded like the last single.

You do use other musicians on this album. Did you consider making it all acoustic with just the two of you?

We just went with what seemed appropriate for the individual tune. Something like “Jug Band Music” sounds kinda odd without a little bump to it.

You’ve mentioned doing the basic tracks in the studio together and then you and Arlen going off on your own to do overdubs separately. What was it like to record like that?

That was by necessity. It was a very natural way for us to proceed. I think we would have done that COVID or no COVID. I was shaking my head with our engineer [and producer], Chris Andersen. Arlen would send us five different takes and they’d all be really good.

Curiously, there’s one really big Spoonful hit that’s not on the album, “Summer in the City.” Why didn’t you do that one?

We tried it and we almost kept it. “Summer in the City” was the only track that, when we were all finished, we said, “The original is still the greatest.” We’re playing well, we’re not doing bad stuff, but it isn’t that marvelous thing. In many cases, I felt like we were touching on that quality on a few of the other well-known songs.

There are some instrumentals on the album. Why did you decide to do some of the songs that way?

Originally, we were going to do an entire album of instrumental versions of the Spoonful hits. But a song like “Jug Band Music” is funny, so if you don’t have the words, it isn’t that fun. That was one. And then “Stories We Could Tell,” Maria Muldaur blew into town [and sang on it], and was so cool.

Some of the guests on this record make it a family affair.

Yes, indeed. [My son] Benson jumped in there on cajon, because there were some situations that really [didn’t require] actual drums, and that is where Ben’s strong suit is. He was working on cajon and he has lots of interesting crap to play that aren’t drums. It was perfect for the project. And then [vocalist] Lexie Roth is her own story. She heard the instrumental version of “Didn’t Want to Have to Do It” and said, “Please, please, please. You’ve got to give me a shot at singing this song. I love this song.” So we said OK. She really sang that great.

The MonaLisa Twins sing on four songs. Who are they?

Mona and Lisa Wagner are twins, and their father is probably the most notable producer in Austria. He figured out that his two daughters were sneaking in [to his studio] after bedtime and making records. The way that the twins thing happened was somebody had sent me a track of theirs, doing “Daydream,” the two of them, one ukulele and one guitar. And it was great. It was adorable. This is when they were probably 16 or 18. My little compliment got back to them and then they wrote to me saying, “Hey, we’d love it if you’d play a little harmonica on this album we’re working on now.” So I did and then another six months went by and they called and said, “Now we’re doing the video for this and we’re having trouble imagining it without you. Could we talk you into coming to Manchester?”

Watch Sebastian sing “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?” with the MonaLisa Twins

You recently played a jug band gig in Bearsville, New York, with Steve Boone as part of the band. What was it like playing with Steve again?

Well, the Spoonful didn’t do anything the way everybody else did. And one of the things they didn’t do was to break up. Everybody wants it to be that me and Yanovsky were at odds, but the fact is he was coming up to hang out with me and play a Stratocaster, and then go to the races, because he liked the horses. So he’d be in Saratoga, not that far away. We were actually seeing each other within four to six months of the breakup. And then also, by 1970, I had been engaged to play the Isle of Wight [festival in the U.K.]. So I go to the Isle of Wight. I do the set, and it goes off well and the audience wants more. I notice Zal, who has has come as Kris Kristofferson’s accompanist. I finish my encore, I go off. I go to talk to Zal and I say, “We could do ‘Make Up Your Mind’ or we could do ‘Jug Band Music.’” We had a second encore that we did together. That’s just by way of explaining the Spoonful breakup. It was painful, I don’t deny any of that, but it was a thing that we did very unconventionally.

Does it bother you that Steve and Joe Butler have been performing as the Lovin’ Spoonful for many years now?

I don’t know what else you do if you’ve done what we did. I can’t attest to the quality or anything. I’ve never seen the show. [People ask] “Are you and Steve getting along?” I say, “We’re joined at the hip.”

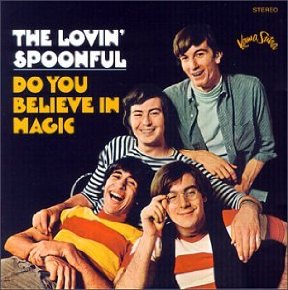

I want to ask you about a few of the Spoonful songs that you remake on the new album. We have to start with “Do You Believe in Magic.” Did you know when you recorded that song that it was a hit?

I want to ask you about a few of the Spoonful songs that you remake on the new album. We have to start with “Do You Believe in Magic.” Did you know when you recorded that song that it was a hit?

Yes. I can’t do false modesty in the case of “Do You Believe in Magic.” And, by the way, I was still saying, “This is a huge hit,” when we had been turned down with the record by every record company in New York City.

How did you end up on Kama Sutra Records?

They were there! (laughs) That happened because we had already signed a publishing deal, being idiots, with [Charles] Koppelman and [Don] Rubin. Their office was down the hall from what was developing as Kama Sutra Records. It was still just a subsidiary of MGM. But I have to say that [label founder] Artie Ripp, a famous ripper in that era, was really the first guy to say, “This is huge.”

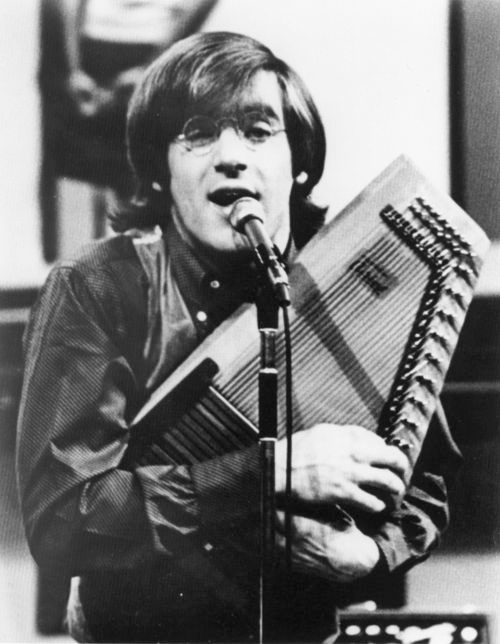

When you played some of your first TV shows with the band, you were playing an autoharp, an instrument mostly associated with folk and country. I think most rock fans probably had never seen one before you showed up with it. How did you come to play that instrument and how did you incorporate that into a rock and roll band?

That all started because I was, for five summers, working as a counselor at a really great New Hampshire music camp. I was playing mostly guitar and there were two sisters who were very knowledgeable about folk music, because one of the sisters’ best friend was Mimi Baez [Fariña], whose sister was Joan. I had really been concentrating on the Duane Eddy songbook.

Watch the Spoonful perform “Darlin’ Be Home Soon” on The Ed Sullivan Show

The Spoonful were sort of the house band at the Night Owl Café in Greenwich Village. What are your most prominent memories of that scene in the mid-’60s?

That was tremendously exciting and a wonderful preparation for what was to come. I did a Judy Collins session, her version of [Eric Andersen’s] “Thirsty Boots.” A guy came in and he says, “Hey, we’re doing this thing at the Playhouse Café. Me and my partner, [singer-songwriter] Fred Neil, are playing there and you ought to play a little harmonica with us.” That was Vince Martin. I go down to the Playhouse, and I’m being slightly scrutinized, skeptically, by Mr. Neil. They play a few tunes and then I play along for a couple of tunes, and Fred’s starting to warm up a little bit. He is having some kind of problem with his 12-string guitar. I just stick out my hand and say, “Give it to me.” The reason is that what I do all day during that era is work at this little Italian classical guitar factory. So they find out that I can tune these instruments quite well. Fred strummed a D chord and gave me a little surreptitious look like, well, OK. That was the beginning of a relationship that became much more serious when Paul Rothchild began recording Martin and Neil for their album Tear Down the Walls and then a year or so later when Fred Neil made Bleecker and MacDougal. Those two projects had me on harmonica, Felix Pappalardi on bass and Peter Childs on guitar.

You were playing mostly on folk sessions before the Spoonful. Was it difficult to make the transition to rock and roll?

No. People think that I was a folkie or something. To me, guitar playing got exciting when I was trying to learn the intro to [Buddy Holly’s] “That’ll Be the Day.” And I was immersed in the Duane Eddy songbook. Also, I was playing guitar for five winters at a prep school in New Jersey, where there was a doo-wop group. They quickly realized that they could improve their sound if they had a guitar player and I became their guitar player. So, really, the stuff that I was into in the winters was trying to play in a dance band so that I could go to girls’ schools, because that’s the only way that boys’ school guys got to see girls, at these dances. I could do more dances if I could continue to play than if I could dance.

What is the story behind “Daydream”?

Originally it was me entertaining myself, trying to sound like Geoff Muldaur, one of the great vocalists of that moment. “Daydream” was tremendously influenced by the Jim Kweskin Jug Band and Muldaur’s vocals. I’ll let you in on a little secret, which is that we played that tune until we had, I think, 26 takes. What was happening was at one time or another, there’d be a little out-of-phase-ness about it. So we finished the day and [producer] Eric Jacobsen said, “Well, that was great. I’ll see you tomorrow. So long.” Yanovsky and I are looking at each other because we know we didn’t get it. We had some sections where it was real smooth, but we didn’t get it all the way through. So I go out the door, and as I’m leaving. I look back at Jacobsen and I make a gesture, like “Get out the [razor] blade [to edit the tape].” And what he did was erase one verse that wasn’t marvelous and add a verse that was. The way we disguised it was by adding things like Yanovsky’s little [sings the song’s repeating riff]. And Steve Boone, somewhere in about the third verse, plays this piano… I added the harmonica, which was really derivative of “Deep Purple” [the 1963 hit by Nino Tempo and April Stevens]. And there it is, a daydream kind of thing.

What was Eric Jacobsen like as a producer?

Eric Jacobsen is one of the great undiscovered geniuses of his era in the medium that he was working in, which started with three tracks, went to four tracks, and eventually, of course, got to eight tracks. We were trying to compete with Beatles. What can go wrong? Jacobsen and I had begun talking about a kind of Lovin’ Spoonful idea before Zally and I had begun hanging out. He introduced me to [folk singer-songwriter] Tim Hardin. I was in a fifth-floor apartment and Eric Jacobsen took the apartment next door. I mean, this stuff you can’t plan on purpose. We would meet in the hallway every now and then, and I’d say stuff like, “Man, that guy you’re playing, that’s cool.” Then one afternoon he comes home and he’s kinda dejected. I open my door. He says, “So, John, tell me what you really think about this vocalist [Hardin] you’ve been listening to through the wall.” I said, “He’s the greatest song stylist since Elvis.” Jacobsen flipped. He said, “That’s what I’ve been, saying.” One night there’s a knock on the door and I open it up and it’s Tim and he’s looking kind of intense. He says, “I know you’re gonna be playing with me tomorrow.” I said, “That’s right.” He said, “Well, there’s something that you don’t know.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Tomorrow you’re gonna play better than you’ve ever played in your life. And you know why you’re going to play better?” “No, man.” “It’s because you’re going to be playing with me.” He turns around and walks away. And so the next day, I damn well did play better than I ever played in my life. That actually came out, I believe, as Tim Hardin 4.

Let’s talk about “Nashville Cats.” There’s a really big mistake in that song and you know what it is. [Author’s note: Sebastian sings about a “yellow Sun record from Nashville,” but the legendary Sun Records label was based in Memphis.]

I do know. (laughs) It’s because I was stupid.

I thought maybe you were taking some poetic license.

No, but reality gave me a little poetic license, because Sun Records did, only a few years later, have a presence in Nashville. But yes, we know that it was Memphis. And remember, again, I’m writing stuff to mainly entertain Yanovsky very often, in some of these goofy songs, and “Nashville Cats” was really one of those.

It’s safe to say there are more than 1,352 guitar pickers there now.

Most assuredly, but there’s a Nashville nerd who went and researched, in 1966, how many guitar players were in the Nashville union. And he said, “You know, you were only two or three hundred off.” I mean, that’s close enough. The song totally happened because the Spoonful played Nashville and we’re all excited and we feel like we kind of did OK. We’re kind of feeling self-congratulatory. We’re gonna go have a beer at the local Holiday Inn basement. We go in there and get beers when this guy shows up with a Telecaster and this crappy old amp. He sits down on the amp. There’s no stage. He starts playing and it’s incredible what comes out. It’s this Chet Atkins thing that starts going jazzy; it’s what I would term hillbilly jazz. Yanovsky and I are gobsmacked. We end up back in the hotel room—we ‘re sharing hotel rooms—and we both are saying, “How is it that this guy that doesn’t even have a stage can take us to town, and just kill it, in 20 minutes?” So, anyway, that was why the song got written a few weeks later, in beautiful Quogue, Long Island.

In between “Magic” and “Nashville Cats,” the second single was “You Didn’t Have to Be So Nice.” Any stories there?

That came about in a very happy way. We were playing what was pretty much a strip club in San Francisco called Mother’s. Steve Boone showed up in my hotel room and said, “I got a thing. It’s not a song, it’s just a thing.” He plays me this “thing” and it’s the core of “You Didn’t Have to Be So Nice.” I said, “Steven, let’s sit here for 15 minutes and we’ll have the song finished.” It really did go like that. It was very, very fast. When he would come up with something, you couldn’t get it out of your head.

What about “Rain on the Roof”?

That tune came out in California. I was out there with my first wife and I think it was probably one of the rare rains that happened there.

From the same album, Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful, “Darlin’ Companion” is a great example of the Spoonful doing country music.

“Darlin’ Companion” has a special place in my heart because Johnny Cash and June [Carter Cash] did it [on the At San Quentin album]. That was just to be in the game, in a slightly country and western way.

Being a New Yorker, how did you first hear country music?

I lived on the 15th floor, and about 10:30 at night, [Nashville radio station] WSM started to come in pretty well. That was my first exposure. I really had a lot to learn when it comes to country. I was so immersed [in blues] and I just wanted to be Lightnin’ Hopkins. That was all I cared about from 15 to 18.

I think most fans would say that the Hums album was the band’s artistic peak. Would you agree?

I think most fans would say that the Hums album was the band’s artistic peak. Would you agree?

I think it’s just that we were starting to have a work pattern, that we were beginning to know what each guy’s job was. It sounds dumb, but you can play for a while before you really know that. [On the new album] I’m always just playing the thing, whatever it is, and Arlen is doing the coolest stuff. That certainly has been a recurring pattern in my life.

Another song you re-do on the album with Arlen is “Jug Band Music.” You were in a jug band yourself before the Spoonful. Why do you think jug bands became something of a phenomenon during the folk revival era of the early ’60s?

What happened was the Jim Kweskin Jug Band. We were all highly entertained by the Kweskin band and Peter Stampfel and Steve Weber, the Holy Modal Rounders. I stuff them slightly in the same pocket somehow. I think having [Kweskin’s 1965 Jug Band Music] album come out, having the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music album come out, and having the Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians album, those things were all combining to kind of give us New York guys exposure to some of these styles. I had to go to summer camp to hear [bluegrass pioneers] Flatt and Scruggs. Their first album [Foggy Mountain Jamboree] was a stunner. I was kind of taking the stuff in as it came at me. [Spoonful] songs like “Lovin’ You” are also heavily based on [bluesman Mississippi] John Hurt, who I sat at the feet of many an evening at the Gaslight Café. He began to ask me to play with him. He’d heard me play with Tom Rush.

There’s one song on the new record that was not originally a Spoonful song but a solo tune of yours, “Stories We Could Tell,” a duet with Maria Muldaur. It was covered by the Everly Brothers back in 1972. Do you know how the song found its way to them?

Paul Rothchild comes over to my house one day and says, “Look, I’ve just been asked to produce the Everly Brothers. I know of their personal problem, and I’m trying to make a setting that would not remind them of the old days.” He’s saying this in my little house in L.A., in Laurel Canyon. He says, “We’re thinking of bringing the tape machine over here and recording in your house.” I said, “I get to hear the Everly Brothers in my house?” And to me, the oddest thing was that Paul had me playing a big [Gibson] J-45 guitar in the style of Don Everly. I don’t know why it wasn’t Don, but I did get to do a tape with Don on one side and Phil on the other, and me in the middle with an acoustic guitar. That was a moment when I really had to fight to stay level.

The story of the 1966 drug bust [of Yanovsky and Boone] that eventually led to the demise of the original Spoonful is pretty well known, with Zal being the first to exit. Do you regret that the original lineup ended when it did, or was it time for you to move on anyway?

The story of the 1966 drug bust [of Yanovsky and Boone] that eventually led to the demise of the original Spoonful is pretty well known, with Zal being the first to exit. Do you regret that the original lineup ended when it did, or was it time for you to move on anyway?

I bet you we could have had a few years if not for the combination of the boys getting busted and reporters jumping on it and going into a virtue signaling state. Everybody wanted to make sure that everybody knew how uncool they thought the Spoonful was. What we’re talking about is $280 worth of pot. What was never documented was the tremendous effort that we made to get the guy [who sold the band members marijuana] off. We had hired a very important lawyer but the gentleman in question wanted to have his own lawyer, who wanted to make pot legal. That went badly for him. It was an unfortunate set of circumstances and yes, it broke my heart.

Wasn’t the band basically over when Zally went back to Canada, even though it continued for a while with Jerry Yester on guitar?

Absolutely. There was reason to continue and it was just a very difficult period we all had to live through. I’m getting chastised but I’m in Los Angeles when this whole thing is going down in San Francisco. Truth be told, they were probably buying the pot for me because they were more [into] drinking, not quite so much pot.

You have so many great stories. When are you going to write a memoir?

Never gonna write one. First of all, I’m too dyslexic. I’m good with two and a half minutes, three minutes. Then my attention starts to drift. I don’t want to do that. Also, it’s going to sound like an apology. It’s bad territory for me.

What did you think of Steve Boone’s memoir?

I was glad he wrote it. I had very little qualm with anything he said, believe me. I wanted Steven to be able to tell his story because that’s what never got told.

Sebastian’s recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

4 Comments

I’m surprised they left out the punchline to the amazing guitar player they saw with the Telecaster. Supposedly it was a young Danny Gatton

I had a feeling that’s who it was, but John couldn’t remember the name so I didn’t push it.

I LOVE this interview Jeff; you asked all the big Q’s I’d have asked (save for John’s CSNY affiliation/Deja vu harp), but great stuff! TY

I second John’s appreciation for your interview, Jeff. But I have to ask, as Gatton was a local Maryland legend, what would he have been doing in Nashville back then, and would he even have been old enough?