“Nancy brought the brand into present time, and enhanced its originator, a rare feat indeed. Normally the offspring tarnish; Nancy moved it forward. Lee Hazlewood laid his very soul upon the singer.” –Former Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham

The archival label Light in the Attic has released the first official reissue of Nancy & Lee, the 1968 duets album from Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood. Released on May 20, 2022, this definitive edition features newly remastered audio by the Grammy-nominated engineer John Baldwin and an array of exclusive content, including a new interview with Sinatra, never-before-seen photos and two bonus tracks from the album sessions: an ethereal cover of the Kinks’ “Tired of Waiting for You” and an uptempo version of “Love Is Strange” (first made famous by Mickey and Sylvia in 1956).

When Nancy, the eldest daughter of Frank Sinatra, first met Hazlewood in 1965, she was a demure, 25-year-old divorcée, who was struggling to find her place as an artist amid the changing musical landscape. At the urging of her label, she was introduced to the Oklahoma-born songwriter, who had found success working with guitarist Duane Eddy. While Sinatra and Hazlewood hailed from vastly different worlds, they were about to embark on a partnership that would change the course of their lives. Just months after meeting, Sinatra scored her first #1 hit with “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.” Written and produced by Hazlewood, the song became Sinatra’s signature tune, transforming her into a confident and commanding feminist icon.

Initially, Hazlewood maintained a behind-the-scenes role with Sinatra, enlisting arranger and composer Billy Strange, as well as other members of the Wrecking Crew (the famed Los Angeles session musicians) for the singer’s best-selling 1966 debut LP, Boots. But when they returned to the studio later that year for Sinatra’s sophomore effort, How Does That Grab You?, Hazlewood joined the singer for a duet of his song, “Sand.” Over the next year, as Sinatra’s star rose, the artists continued to collaborate in the vocal booth, finding success with “Summer Wine,” “Lady Bird” and the cinematic “Some Velvet Morning” (all penned by Hazlewood). In 1967, just months after Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash scored a country hit with “Jackson,” Sinatra and Hazlewood released a pop version of the offbeat song, landing in the top 10 across Europe and peaking at #14 in the U.S.

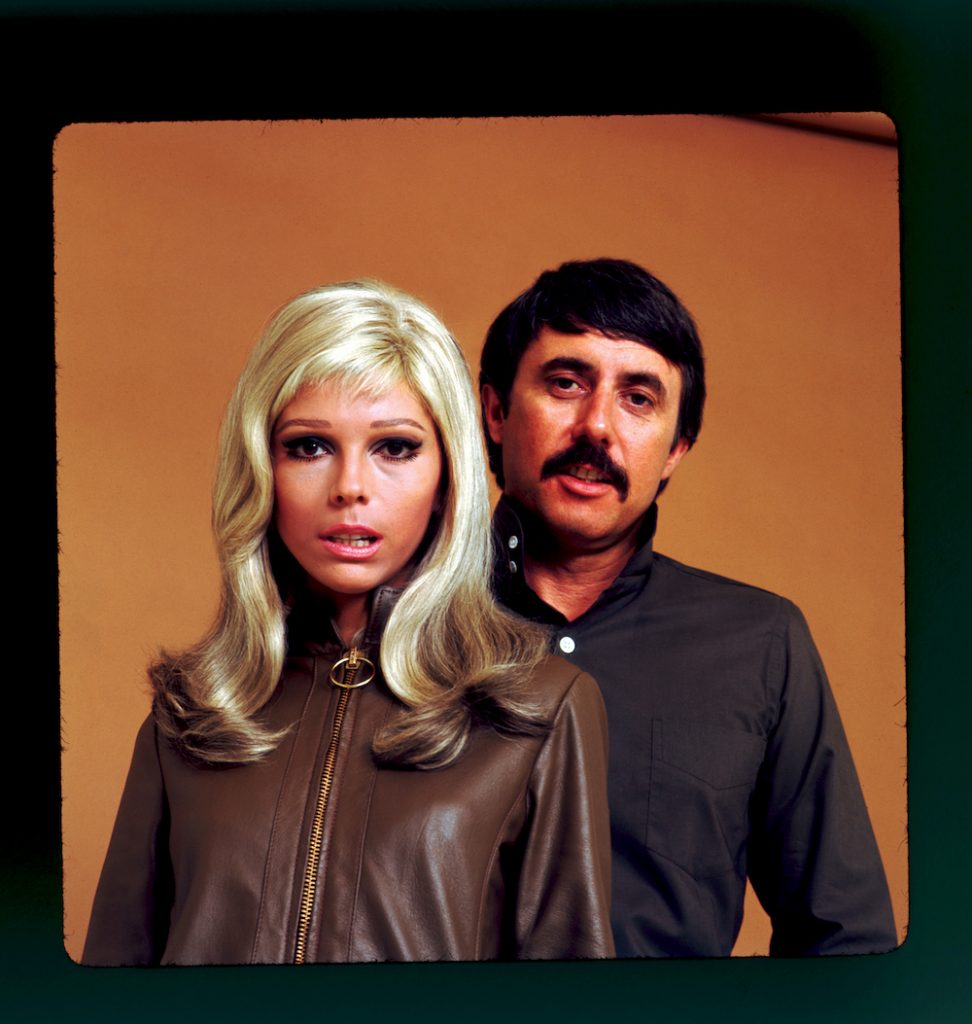

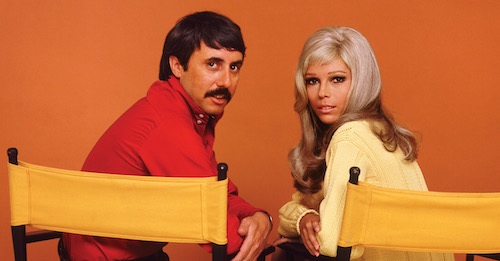

Recalling her duets with Hazlewood, Sinatra says, “We used to call it Beauty and the Beast! Voices with no blend.” Indeed, no one could have predicted that these two contrasting voices (and personalities) would work together quite so well. Praising the duo’s “sonic alchemy,” Hunter Lea writes, “Rarely in music has there been such an unlikely collaboration: Nancy, the sassy and sweet songstress contrasted by Lee, the gruff, psychedelic cowboy. A harmonic partnership that defies conventional logic yet yields so much beauty.”

Recalling her duets with Hazlewood, Sinatra says, “We used to call it Beauty and the Beast! Voices with no blend.” Indeed, no one could have predicted that these two contrasting voices (and personalities) would work together quite so well. Praising the duo’s “sonic alchemy,” Hunter Lea writes, “Rarely in music has there been such an unlikely collaboration: Nancy, the sassy and sweet songstress contrasted by Lee, the gruff, psychedelic cowboy. A harmonic partnership that defies conventional logic yet yields so much beauty.”

Before long, it seemed only natural for the artists to release an entire album together. In addition to compiling their recent duets (many of which appeared on Sinatra’s solo LPs), the duo recorded several new covers and Hazlewood originals. Billy Strange and the Wrecking Crew provided lush orchestral arrangements, as the two artists performed a range of material, including folk, pop and country songs, with a twist of psychedelia.

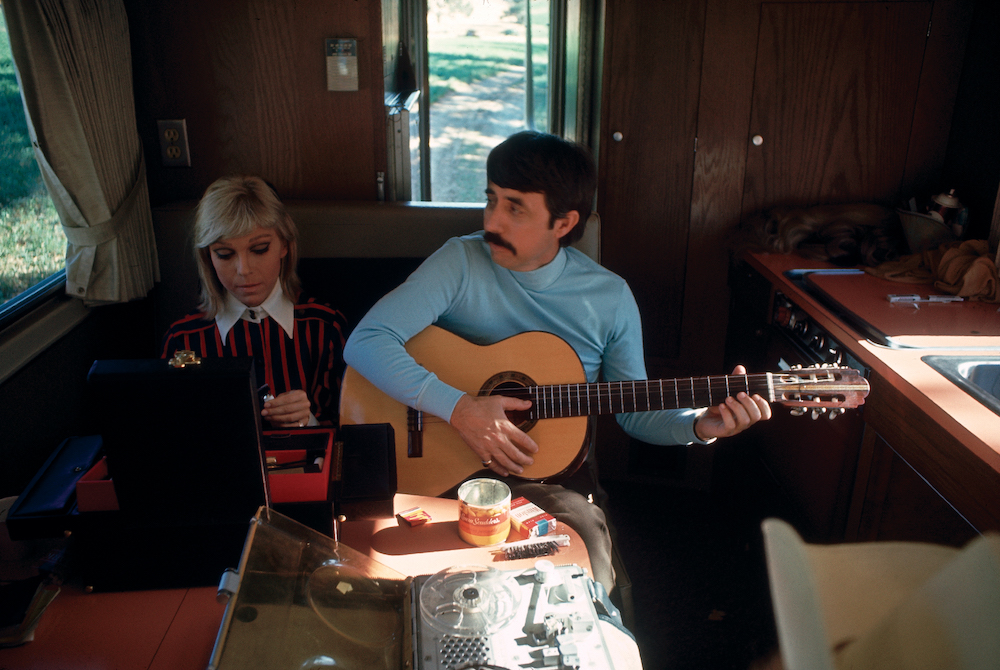

Throughout the album, a palpable chemistry can be heard between Sinatra and Hazlewood, from the frisky banter on “Greenwich Village Folk Song Salesman” to the tongue-in-cheek delivery of ”I’ve Been Down So Long (It Looks Up To Me).” But the artists also reveal their softer sides, particularly in the romantic balladry of “Sand.” Their languid rendition of “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” meanwhile, is downright erotic, despite the lyrics. But, as Sinatra asserts, her decades-long relationship with Hazlewood was always platonic. “We had sort of a love/hate relationship,” she explains. “Maybe it was a sexual tension because we never had any kind of affair. I don’t know exactly what it was, but it worked.”

That je ne sais quoi certainly did work. Upon its release in the spring of 1968, Nancy & Lee became a critical and commercial hit on both sides of the Atlantic, peaking at #13 on the Billboard 200 and #17 in the U.K. By 1970, the album was certified gold by the RIAA. Over the decades, however, the appeal of Nancy & Lee has only grown, while the album has amassed an enduring cult status that few titles achieve. Multiple generations of artists, including Sonic Youth, Lana Del Rey and the Jesus and Mary Chain, have cited Nancy & Lee as an influence.

Sinatra, born June 8, 1940, reflects fondly on her time with Hazlewood, who died in 2007 at age 78. “The most fun was when there were two mics in the studio, and Lee was on one and I was on one,” she recalls. When asked about the lasting appeal of Nancy & Lee, the artist credits much of its success to her partner. “Lee has a following that continues to this day. He’s beloved; people love him all over the world.”

In 2021, this author interviewed Nancy Sinatra about her work with Hazlewood and her career in general.

Best Classic Bands: What did you learn from watching recording artists like your father, Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr.?

Nancy Sinatra: I think we learn from everything as we go along. Just about anyone will tell you that the phrasing is solely dependent on the song and the lyrics, at least it should be, although I know there are people who just sing on the beat no matter what. It’s a shame they don’t experiment a little bit. I don’t think I copied anybody. I didn’t like my early [1961-1964 Reprise] records and my “Nancy Nice Lady Voice” and the records [produced by Tutti Camarata and Don Costa]. It wasn’t really me. And then I was very eager to make the change later that Barton [Barton Lee Hazlewood was his full name] was asking for after [producer] Jimmy Bowen suggested Barton. I was going to be dropped from the label.

In 1965 you employed a new lower voice register in your recordings like “Boots.”

It was up to the song. The songs were so different and we were experimenting with songs that were recorded by men and I was very fond of changing lyrics around, like [the Beatles’] “Run For Your Life” and songs like that. I felt, in those days, having a girl—not a woman—sing them was just better.

You have always said you knew “Boots” was going to be a smash, and Chuck Berghoffer’s seductive opening bass line was a crucial aspect of the recording.

I absolutely knew it was going to be a hit. The “Boots” bass line is unique and special; you know what the song is the minute you hear that bass. That was Barton’s idea. He played it on the guitar, which is hard to do, because the guitar has frets. It’s s a quartertone line and you can’t play quartertone with a fretted instrument. And Chuck’s upright bass, he was able to slide down that intro. Yes, that was Barton’s doing, too. He wanted that from Chuck. I thought the bass was the star of that record.

You had a teacher/student relationship with Lee Hazlewood. Tell me about the pre-production period when you first heard and reviewed material he would present, which he often wrote.

Well, since every recording begins with the song, mostly Barton and Billy would come over to my house. “We’ve got a new song. We want to come over and work it out.” The process was quite simple because they pretty much had it set in their heads before they played a song for me. Lee was such a fine producer and he knew where a horn line was gonna go. And he pretty much knew what the horn line was gonna be. “Arkansas Coal” and “Paris Summer” are two of my favorites. “Down From Dover,” a Dolly Parton song. We were very serious. I mean we were very serious.

And then there were duets, where you really complement each other.

I don’t think there’s been anybody else who has captured that, any other duo. I really don’t.

There was a sexual tension but you weren’t romantically involved with Lee.

It was acting, good acting. Yeah, we did have a chemistry and we capitalized on it. I trusted him. One of the essential parts of recording in those days was the tape reverb, which for people who don’t know is a way of creating a kind of compounded echo chamber. Now I guess there are ways to create the analog sound digitally, but when we were making all those hit records, there was a reel-to-reel tape machine in the booth spinning constantly during sessions. I don’t know how to explain it technically, but it added depth and it was an honesty that digital doesn’t have. It’s like when you record live and the room sounds are happening and the chairs are creaking and people are breathing, that sort of thing. It just makes a difference in the way the recordings sound. When I was doing records later on in my life, I had to really scrounge around to get that sound.

Related: Read more about the making of “These Boots Are Made for Walkin'”

Billy Strange arranged and played guitar on “Boots” and he did the instrumental arrangement for your duet with your father on “Something Stupid.” How did he enter your life?

Lee brought Billy over to my mom’s house after my divorce [from singer/actor Tommy Sands]. Lee dictated to Billy what he wanted to hear on the “Boots” single. Billy understood. He was just learning how to arrange. He started pretty much strictly with country and then California rock. His guitar playing was extraordinary. He’s made some wonderful albums over the years. Unfortunately, they got buried somewhere along the way. Billy bled that guitar. His soul and pain and joy came out through that instrument.

Tell me about recording with the musicians known as the Wrecking Crew.

They were absolutely breathtaking to watch. You’d come into a studio and sometimes you’d have written charts, but most of the time you would have chord sheets and they would create almost everything. The arrangements grew as time went on and of course when they worked with my dad or Dean, people like that, they had charts to read. Glen [Campbell] could never read. He listened to the run-throughs and he was so quick he picked up immediately what he had to do and it was without a hitch.

You have said that you also knew immediately that “Somethin’ Stupid” was going to be a hit single. How did that song become part of your repertoire?

Carson Parks, who helped write it, already had a record of it out, with a woman [Gaile Foote] singing. Sarge Weiss [aka Irving Weiss], a song plugger, found that recording and he played it for my dad. He said, “I think this is a great song for you and Nancy.” And my dad said, “Get it to Nancy and if she likes it we’ll do it.” And I loved it, of course, from the guitar intro. Once again it is that hook in the intro in the song that grabs me, like the descending bass line in “Boots.” We brought in the key rhythm players at the end of one of the [Antonio Carlos] Jobim sessions my dad had.”

Watch Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood on The Ed Sullivan Show, singing “Storybook Children”

1 Comment

Loved the Jackson song from the first time I heard int in the 1960s.