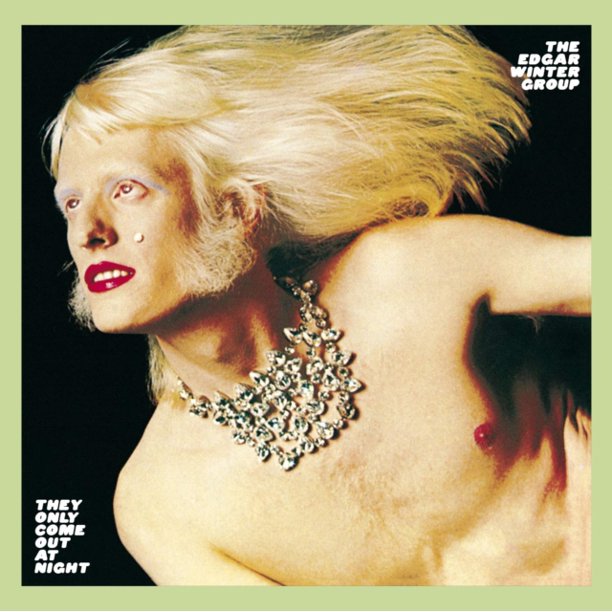

It’s fair to say that with his album, They Only Come Out at Night, released in November 1972, Edgar Winter created a monster. Not only was the album’s lead single the instrumental “Frankenstein” (which received its own RIAA gold certification, amidst the album’s platinum certification), but it spawned two other hit singles as well: “Free Ride” and “Hangin’ Around.” And FM rock radio delved several tracks deeper.

It’s fair to say that with his album, They Only Come Out at Night, released in November 1972, Edgar Winter created a monster. Not only was the album’s lead single the instrumental “Frankenstein” (which received its own RIAA gold certification, amidst the album’s platinum certification), but it spawned two other hit singles as well: “Free Ride” and “Hangin’ Around.” And FM rock radio delved several tracks deeper.

How did Winter, who’d recorded two musically adventurous if far less commercially successful albums with Entrance (self-produced, and featuring brother Johnny Winter and his band on its cover of “Tobacco Road”) and Edgar Winter’s White Trash (produced by Rick Derringer, featuring Johnny, plus horn and string sections), find his breakthrough vehicle a year later?

Turns out it took a village.

Edgar Winter, whose Grammy Award-winning 2022 release is titled Brother Johnny—a tribute to his late bluesman brother—felt he first needed to demonstrate his artistry with 1970’s Entrance.

Related: More about the Brother Johnny tribute album

“I was thinking specifically and most especially about Clive Davis in the making of this album,” Winter said. “I had never had a particular desire to become famous or sell a lot of records. I was more interested in jazz, blues and classical rather than pop music.

“I’d explained the experimental nature of Entrance to Clive, and my vision and desire to expand and broaden musical horizons through the fusion of musical forms not usually played or heard together. Clive believed in me as an artist and encouraged me to follow my dream. If not for his artistic understanding and support, that first album might never have been made. And that beginning, along with Clive’s trust, inspired my evolution as an artist to develop, moving on to other things I might otherwise never have explored or discovered.

“I felt the record company (and Clive in particular) had supported me faithfully, giving me generous advances which I doubted would ever have been fully recouped unless I came up with a really big album. So, for the first time in my career, I decided to dedicate myself to making a really successful album.

“I knew that in order to do this, I would have to form a completely different kind of group,” he concluded. “I never expressed any of this to Clive directly at the time, so he may well be surprised to hear it. I just did it!”

Indeed it was. They Only Come Out at Night proved a wellspring of pop singles: “Free Ride,” “Hangin’ Around,” “We All Had a Real Good Time” and a song that might have crossed over country, “Round & Round.” (That’s producer and longtime collaborator Rick Derringer on pedal steel guitar, giving the song its Poco-esque groove.)

Indeed it was. They Only Come Out at Night proved a wellspring of pop singles: “Free Ride,” “Hangin’ Around,” “We All Had a Real Good Time” and a song that might have crossed over country, “Round & Round.” (That’s producer and longtime collaborator Rick Derringer on pedal steel guitar, giving the song its Poco-esque groove.)

If Winter, born Dec. 28, 1946, had a secret weapon in creating They Only Come Out at Night, it was singer and multi-instrumentalist Dan Hartman, then 21 years old, who became a pop and disco hitmaker in his own right in the later ’70s an early ’80s. Hartman wrote or co-wrote the album’s hits (save for “Frankenstein” which was a Winter composition).

Watch Edgar perform “Free Ride” with Ringo Starr and His All-Starr Band

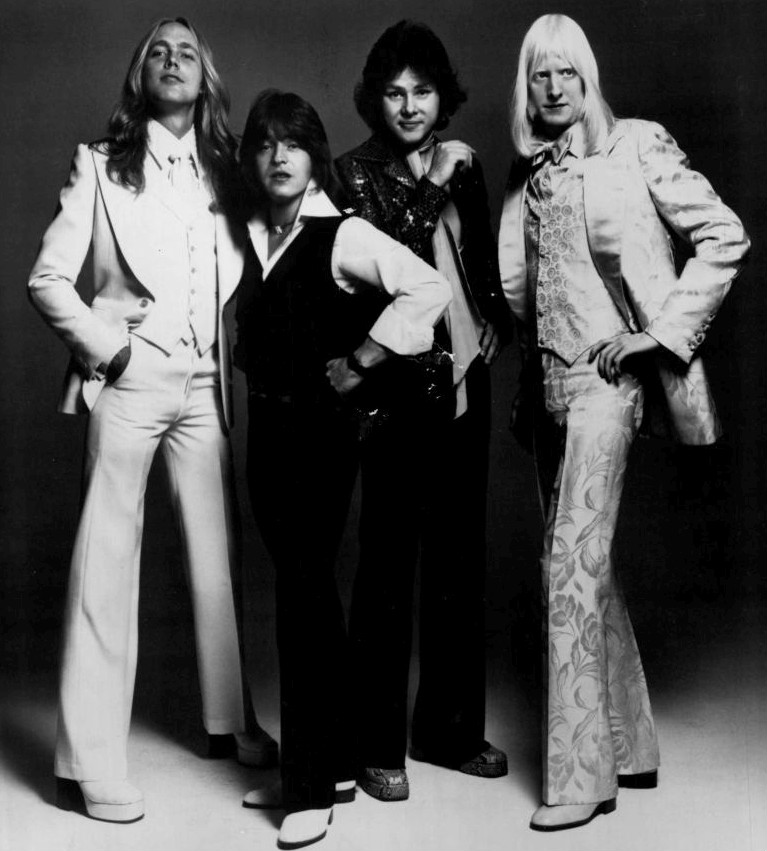

“Given my intention to make an album with mass appeal, I determined to assemble the quintessential All-American rock band,” Winter said. “I wanted to find members who were not only great musicians, but who could write, sing and play. I knew image would be important, so I had to have guys with the right look, stage presence and charisma who could contribute to the overall direction of the band. They didn’t have to already be stars, but they had to have star quality and potential. In short, a real ‘super band!’

“This effort turned into an all-out massive talent search. I remember listening to hundreds of demo tapes over a period of months. Then one day I played this tape from a guy named Dan Hartman from Harrisburg, Pa., and I instantaneously knew I had a major band member and collaborator.

“We flew Dan up to New York, and within an hour of playing together, I knew this was the beginning of the band. I heard Dan play guitar (his main instrument) bass, piano and drums. He not only played them, but played them well. Dan had a real pop-rock radio voice, and could also sing soulful R&B. And, perhaps most importantly, he was a truly great songwriter. Absolutely perfect! I couldn’t have asked for anything more.”

Watch the Edgar Winter Group perform “Tobacco Road” live in 1972

The other key ingredient in the album’s sound was San Francisco-bred guitarist Ronnie Montrose, whose namesake hard-rock band recorded into the later ’70s and ’80s. He also recorded several solo albums.

Winter explained: “Dan’s main instrument had always been guitar, but I’d already seen Ronnie Montrose with both Van Morrison and Boz Scaggs. Dan loved pop music and there was a kind of youthful innocence about him—and his music. Ronnie, on the other hand, was a real rocker, and had the kind of wild, almost rebellious, bad boy image I thought would be perfect for the guitar spot. Bands are all about chemistry, so I thought this contrast would be the perfect combination, and man, it was!

“We played for a while with two guitars, Randy Joe Hobbs (from the McCoys) on bass, and Johnny B. (from Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels) on drums. However, I was eventually able to convince Dan to switch over to bass for what I considered the good of the band. To me a five-piece band is just a little unfocused; you tend to lose track of who’s who. Four is just the right balance and perfect number. Everybody is easily identifiable and retains their own individuality, personality and identity.

It was Montrose who brought in drummer Chuck Ruff. “It was at this time (as we were already changing the band) that Ronnie spoke up, recommending Chuck Ruff to try out as the permanent drummer. They had played in s band together, and Ronnie seemed absolutely certain he would be the right guy. Johnny B was (and is) a great drummer. He still comes out to see us whenever we’re in Detroit, but at that time he just didn’t seem quite sure exactly what he wanted to do.

“I had grown to know and trust Ronnie well enough to realize he wouldn’t be making this suggestion if there weren’t really something to it. So we flew Chuck out to meet and hear him play. As soon as Chuck walked in I thought, man, this guy’s got the look! Tall, long, blonde, curly hair—strong chin, handsome features. I knew the girls were gonna go crazy for him!

“Then he sat down at the drums, and it was magic. Ronnie broke into one of those grungy, driving, speed-demon, power riffs, and we just started to jam. At first, I was lost in the music, immersed, enthralled. Then I looked over at Chuck, and couldn’t believe my eyes. The groove was there, intense and solid. He was a really good drummer, no doubt. But he looked phenomenal.

“I’d never seen anyone with so much love and passion for the instrument. His demeanor and attitude behind the kit was nothing short of electrifying. Chuck played the drums with his whole body, every fiber of his being. When he shook his hair, even it seemed to dance with the music.”

“At that moment,” Winter continued, “I knew this was the band! Ronnie’s power-driven high-energy guitar presence, leaps and Townshend-like windmill arm motions; Dan’s great pop sensibility, songwriting, radio voice and gritty rock vocal ability; I, with my totally unique look, multi-instrumental presentation, stratospheric, screaming, gymnastic vocal style; and Chuck’s awe-inspiring energy and persona at the drums. This was a band people would not only love to hear, but would be dying to see!”

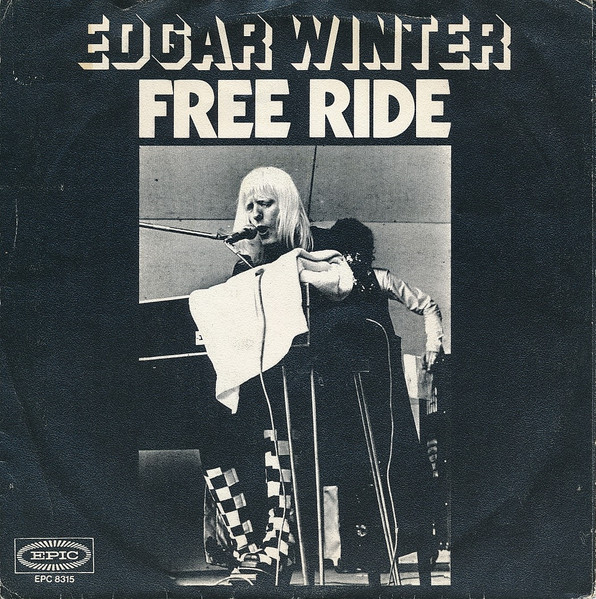

So during August and September 1972, the newly formed Edgar Winter Group went into New York’s Hit Factory and Sterling Sound studios. Rick Derringer produced while contributing slide and pedal steel guitars; Bill Szymczyk (later a production star in his own right) served as engineer. For the hit single “Free Ride,” Randy Jo Hobbs, who worked with both Winter brothers, made a guest appearance on bass, with Detroit Wheel Johnny Badanjek on drums.

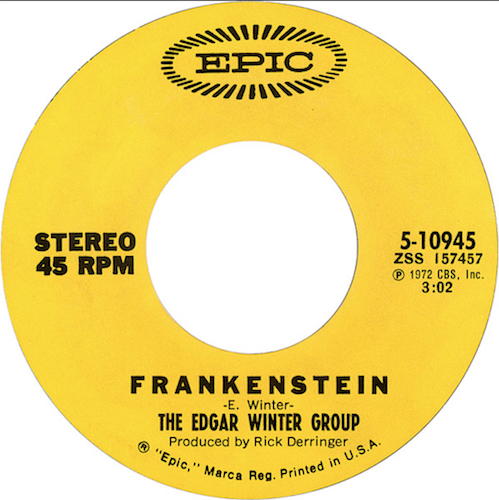

As for the 900-pound monster in the room, “Frankenstein” was based on a riff that Edgar and Johnny played in the ’60s. The song, released as a single on Feb. 21, 1973, actually made it all the way to #1 in the nation, almost unheard of for an instrumental! Here’s how it all happened.

As for the 900-pound monster in the room, “Frankenstein” was based on a riff that Edgar and Johnny played in the ’60s. The song, released as a single on Feb. 21, 1973, actually made it all the way to #1 in the nation, almost unheard of for an instrumental! Here’s how it all happened.

“As you may know, my first concert experience was playing with my brother Johnny and his blues trio,” Edgar reflected. “Back then, I considered myself more of an instrumentalist than a singer. And since I played a lot of instruments, I thought it would be cool to come up with a song that featured me on several different ones (organ, sax and drums). And so it was that I wrote the infamous riff which became the ‘head’ of the monster that still stalks the world today.” (In jazz, the introductory statement or melody is referred to as the ‘head,” he explained.)

“Johnny used to do the first half of the set with the blues trio, and then he would say, ‘And now, I wanna bring on my little brother, Edgar.’ It was really cool in the beginning, because no one knew who I was, or that Johnny even had a brother. It was like…oh my God, people couldn’t believe it! So, I would come on, sing ‘Tell The Truth’ (a Ray Charles song) with Johnny, do ‘Tobacco Road’ (which started the vocal-guitar duel trade-offs), and then do ‘The Double Drum Song’ (which eventually became “Frankenstein”). What a show!

“So ‘The Double Drum Song’ became the first song I ever wrote and played live without it ever having been recorded! We played it all over the world; and then it was gone and forgotten, Until…the advent of the synthesizer! I had just formed the Edgar Winter Group, discovered the synthesizer, and gotten the idea of ‘wearing’ the keyboard with a strap. So, I started looking for a song I could use to feature the synthesizer as a lead instrument. And then I had an inspiration…wow! I’ll bet that riff to the old double drum song would really sound great with that reinforced sub-sonic synth bottom! And it did!”

“With the inspiration of the synthesizer,” he added, “I really went to work: first designing and creating totally new sounds, then writing various different sections to display each one, and finally fitting them together into an all new contemporary musical context. I decided to replace the drums with timbales for the percussion sections. This eliminated the problem of two drum kits on stage, and actually made it more interesting. We finally worked it up into a killer showpiece—no pun intended—and started playing it live. The response was incredible; it was a showstopper! In fact, it was so powerful; it just had to close the show, as it does to this very day.

“All this, however, was yet only the beginning. The song still had no name; we had just started calling it ‘The Instrumental,’ and I never had any intention of recording it. You might ask, how could you not intend to record such an interesting and exciting song? The answer is simple. Back in those days there were two kinds of songs: live songs and recording songs, and this was definitely a live song. Radio wouldn’t play anything over four minutes, and this thing was over 15. Also, I believed the real direction of the Edgar Winter Group lay in the co-writing between Dan Hartman and myself. I saw ‘Free Ride’ as the potential big hit.

“Recording was a different process back in the ’70s. Groups frequently went in with just a few songs, and actually wrote and created the album in the studio. Consequently, when any jamming was going on, tape was always rolling. The instrumental was one of our favorites to warm up with, so there were several super-long versions of it on tape. Our album (which was itself still untitled) was almost completed. We were just sitting around talking one night when Rick [Derringer] said something like, ‘Why don’t we try mixing that live song, the instrumental?’ Bill [Szymczyk] really liked the thing and thought it would be really fun to mix. I thought it was kind of a crazy Idea, but I like crazy ideas, and I loved the song. So I said, ‘Sure! Why not?’

“The only real problem was its extreme length. Back in those days, the only way to edit a song was to physically cut the master tape into pieces, rearrange them and put them back together with splicing tape, a sort of musical jigsaw puzzle with recording tape. This seemed like a great excuse to get even more blasted than usual and have a kind of (finishing the album editing party) to wind things up. It’s a painstakingly methodical and laborious task (much like cutting a diamond). One mistake, and you’re done! I can still remember the tape all over the control room; spilling over the console, folded up on the sofa, draped over the backs of chairs: it was everywhere!

“It was so confusing; we couldn’t figure out how to put the thing back together. Somebody said, ‘Well, I know this is the main body on the couch; and I think the head’s over there.’ Finally, we got it all back together; and man, it sounded cool! Let’s hear that again! So we hit rewind. Chuck Ruff was sitting by the tape machine. He looked mesmerized, almost in a hypnotic trance, just watching all those edits spin by. And then, Chuck mumbled the immortal words: ‘Wow, man, It’s like Frankenstein.’ We all looked at each other. That’s it! The name of the song… ‘Frankenstein’! “

The song has been covered by artists as diverse as Phish, They Might Be Giants, thrash metal band Overkill and even British I.R.S. Records band Doctor and the Medics, who wrote lyrics for the track.

In addition to “Frankenstein,” Winter is most fond of “Free Ride.”

“Every time I perform it, I think of Dan, his amazing talent, and how much fun we had writing and playing together.”

Fifty years after They Only Come Out at Night, Edgar Winter remains active, having released his tribute to Johnny. Sadly, there were three casualties along the way: Dan Hartman died on March 22, 1994, from complications of HIV. Ronnie Montrose died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, reportedly battling both depression and prostate cancer, on March 3, 2012. Chuck Ruff, who went on to play with Sammy Hagar in later years, died October 14, 2011, following a long illness.

In closing, Winter has a kernel of wisdom for upcoming musicians: “Just play the music you most love and have real fun playing. That will communicate, and people will feel it. I think that’s why ‘Frankenstein’ worked so well. We were just having fun. There are lots of people who will tell you what’s commercial and what you ought to play. But just follow your heart and you can’t go wrong.”

Bonus Video: Watch Edgar and brother Johnny Winter perform “Frankenstein” live

4 Comments

Back in the 70’s Edgar and Johnny both played Burlington Vt. a bunch. I think they were living in Montreal? It was always a great show and one of the reasons I have this incessant ringing in my ears. Will somebody answer the damn phone? Haha.

Edgar had Clive in his corner, but also Steve Paul for management. Steve was a giant, and worked as hard for his artists as any manager during that period. Steve managed Dan Hartman and Rick Derringer (and Johnny Winter) as well, so the Edgar Winter Group kept it in the family. RIP Steve Paul

I was lucky enough to see both Johnny and Edgar perform live at a place who’s claim to fame was that it had the world’s longest bar.

The acoustics in that venue were second to none. The long ARP synth segment to “Frankenstein” echoed throughout the room in a manner that was mind-blowing.

My love for Johnny and Edgar’s music goes incredibly deep. No one I knew even acknowledged knowing about these two incredible musicians. But I followed their musical careers faithfully and bought all of their albums.

Didn’t someone in the band (I’m thinking Dan) buy a space suit (that cost 50k) for one of the EWG tours in the 70s?