Some fans consider it the best album the Rolling Stones ever made, but they are in the minority. Many more have opined, since its release on December 8, 1967, that Their Satanic Majesties Request is a disaster, alternately described as an embarrassment, rubbish or, perhaps most pointedly, a blatant rip-off of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—conceptually, musically, even visually.

Some fans consider it the best album the Rolling Stones ever made, but they are in the minority. Many more have opined, since its release on December 8, 1967, that Their Satanic Majesties Request is a disaster, alternately described as an embarrassment, rubbish or, perhaps most pointedly, a blatant rip-off of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—conceptually, musically, even visually.

Then there are those whose verdict falls somewhere in between, including the band members.

Keith Richards reportedly called the album—the Stones’ sixth in the U.K., eighth in America—”a load of crap.” Mick Jagger has said that its songs are “not very good.” Bill Wyman, the former Stones bassist, has gone on record as complaining that the album was recorded chaotically, with members of the band coming and going from the recording studio at will, sometimes accompanied by large entourages—and that the results show it. The band’s manager and producer, Andrew Loog Oldham, was so fed up with what was happening that he walked out on the Stones, never to return. They produced the album themselves.

Only drummer Charlie Watts seemed to have a good time. “The sessions were a lot of fun because you could do anything. It was so druggy—acid and all that,” the late Watts once said.

Despite all of that, someone must have liked it: The LP reached #3 in the U.K. and #2 on the U.S. Billboard album chart, the same ranking achieved by its two predecessors, 1966’s Aftermath and early ’67’s Between the Buttons. And it did better than the album that came after it in 1968, the highly regarded Beggars Banquet, which peaked at #5 in America.

After a couple of decades of slagging the album, or wishing it could simply disappear from their discography, the Stones cautiously embraced parts of it. adding two songs from the album—“2000 Light Years From Home” and “She’s a Rainbow”—to tour setlists, in 1989-90 and 1997-98, respectively.

In order to understand why the album garnered such mixed reviews among even the most ardent Stones fans, it’s imperative to take into account the time and circumstances in which it was made. Although the Stones began laying down tracks for their new album in early 1967, by the time they finished it that fall, much had changed both in rock music itself and the culture that nurtured it. The experimental sound of what was already being called psychedelic music, or acid-rock, was in full bloom: New names like the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Doors, the Mothers of Invention and Pink Floyd had seemingly appeared out of nowhere, expanding rock’s boundaries beyond anything that might have been conceived of a few years earlier.

It was all moving at a lightning pace. The new rock music of 1966 had, for the most part, been characterized by an aggressive, tougher approach than the recent folk-rock that rose in ’65 had presented; some bands simultaneously began stretching out instrumentally and lyrically, applying new technologies and conceptual ideas conjured from a plethora of sources. They were fortunate to enjoy an unprecedented level of creative liberty from their record companies and the concert promoters who were booking them into ballrooms and college gymnasiums: The iron-fisted hand of corporate overlords had begun loosening—the suits didn’t understand what these young longhairs were doing, but they knew it was making them money, and that was the name of the game.

At the forefront, not surprisingly, were the Beatles, who had released their masterpiece Revolver in 1966 and followed it in June ’67 with Sgt. Pepper’s, arguably the most popular—and to many, the most groundbreaking—rock album of all time. Even the Beach Boys, previously considered by many to be an unhip teenybopper band, had turned out a stunning work of art that would influence the Beatles and countless others, Pet Sounds. The Stones, like all of their contemporaries, were riding that wave: growth, progress, evolution—it was vital to a band’s survival. No one could hope to stay alive in 1967 if they sounded the way they did even in ’65. Bands that had dominated the AM radio airwaves in the mid-’60s with short, accessible pop hits—both Americans (Lovin’ Spoonful, Turtles, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Monkees) and British (Yardbirds, Animals, Who)—were moving into more expansive musical areas. At the same time, a new wave of FM radio stations was emerging, eager to give the new music air time. Nothing in rock was standing still.

Between the Buttons had been a killer Stones album filled with great—if not always classic—material (“Miss Amanda Jones,” “All Sold Out,” the country-influenced “Connection”), which had undeniably taken them in new directions, decidedly away from their blues and R&B roots. For its followup, it was necessary to take yet another giant leap, but how far could they go? They were anxious to find out.

Related: Bill Wyman on the Stones’ early days

At least some of that decision, however, would have to be left to fate and the influences they, like most rock musicians at the time, were soaking up. LSD had become a huge presence within the rock community by the so-called Summer of Love of ’67, and much of the new music being produced owed its very existence to the impact the drug had upon the musicians. The Beatles had certainly indulged, and Sgt. Pepper was as much an acid-informed album as any of the day—for many, it was the consummate psychedelic creation.

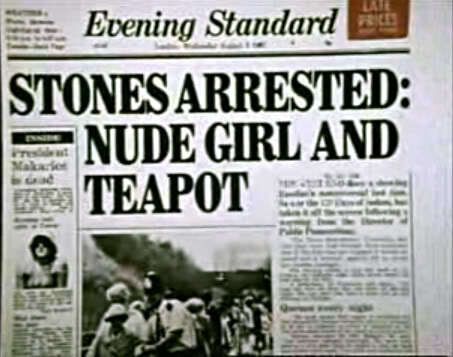

The Stones, too, enjoyed the powerful concoctions of the chemists, perhaps a bit too publicly: On Feb. 12, 1967, during a party at Richards’ Redlands estate, a squad of some 18 police officers descended, informed that drugs—no way!—were being used on the premises. Richards, along with Jagger, Mick’s singer girlfriend Marianne Faithfull and others, were paraded in front of newspaper photographers, who had a field day with the raid, particularly enthralled by Faithfull’s attire—which is to say none, save for a fur rug. It was only after the party that Jagger and Richards—who were allegedly tripping on acid at the time of the constables’ visit—were arrested for drug possession, but the event set into motion a series of circumstances, legal and otherwise, that would paint much of the Stones’ 1967 with a dark hue. By the time the two Stones’ cases were decided in the early summer—small fines and jail sentences that were handily dismissed—the future of the Rolling Stones was in disarray.

The Stones, too, enjoyed the powerful concoctions of the chemists, perhaps a bit too publicly: On Feb. 12, 1967, during a party at Richards’ Redlands estate, a squad of some 18 police officers descended, informed that drugs—no way!—were being used on the premises. Richards, along with Jagger, Mick’s singer girlfriend Marianne Faithfull and others, were paraded in front of newspaper photographers, who had a field day with the raid, particularly enthralled by Faithfull’s attire—which is to say none, save for a fur rug. It was only after the party that Jagger and Richards—who were allegedly tripping on acid at the time of the constables’ visit—were arrested for drug possession, but the event set into motion a series of circumstances, legal and otherwise, that would paint much of the Stones’ 1967 with a dark hue. By the time the two Stones’ cases were decided in the early summer—small fines and jail sentences that were handily dismissed—the future of the Rolling Stones was in disarray.

Still, there was music to be made, the first of it a non-LP single with two new Jagger-Richards compositions, “We Love You” and “Dandelion.” The former song opens with the sound of a jail door closing, a not-very-subtle reminder of the recent troubles. Featuring the core Stones lineup of Jagger, Richards, Wyman, Brian Jones (playing a Mellotron) and Charlie Watts, the single also included freelance pianist Nicky Hopkins (whose rollicking intro to “We Love You” gave the song its forward thrust). It is said that John Lennon and Paul McCartney are on background vocals on that track as well. The single fared well in the U.K. and some other countries but underperformed in the U.S., with “Dandelion” reaching #14 and “We Love You” stalling at #50.

Both of those songs, produced by Oldham, pushed the Stones firmly into the psychedelic arena and tempered any shock that might have accompanied the release of Their Satanic Majesties Request later that year. By the time the LP did arrive, few close followers of the Stones would have been taken by total surprise: This was the kind of music bands were making in late 1967, and a group as cutting edge as the Rolling Stones was not about to offer up a rerun of “Satisfaction.”

Nonetheless, the initial response to Satanic was certainly mixed. Some of its tracks were pure Rolling Stones; others, not so much. The album, recorded at London’s Olympic Studio, opens with “Sing This All Together,” which, as its title implies, is a good-time plea for everyone to come along for the psychedelic ride of a lifetime: “Why don’t we sing this song all together/Open our heads let the pictures come/And if we close all our eyes together, then we will see where we all come from,” goes the chorus, the tune loping along at a medium tempo, Jones coloring it all with Mellotron and saxophone. (Jones, in fact, stays away from his guitar throughout the album, preferring instead to display his versatility on an arsenal of instruments including vibraphone, organ, Theremin and dulcimer.) Nicky Hopkins, as he did on the summer single, joins the band on piano for this track and all but a few others.

Jagger’s voice, on both that lead number and the one that follows, “Citadel,” is in fine form. He seems as comfortable within this looser format as he does on the band’s early, more structured singles. “Citadel” is one of the album’s true gems: Richards’ angular electric guitar lines contrast seamlessly with the Eastern flavor of the melody (again, Jones’ Mellotron). What the song is about is anyone’s guess, but the poetry of Jagger’s lyrics (“In the streets are many walls/Hear the peasants come and crawl/You can hear their lovers call/Candy and taffy, hope we both are well/Please come see me in the citadel”) meshes beautifully with what the band is molding behind him.

“In Another Land,” the third song on the album’s original first side, is where things start to go into, well, another land. Written by bassist Wyman—and the only lead ever sung by him on a Stones album—it’s almost comically fluffy at first. Was this a put-on or for real? Were the Rolling Stones, rock’s baddest of badasses, really opening a song with the lines “In another land, where the breeze and the trees and flowers were blue/I stood and held your hand”? Why, yes, they were! But was Wyman being serious? The first verse ends with “Then I awoke/Was this some kind of joke/Much to my surprise, I opened my eyes,” so you be the judge. Adding to the weirdness factor, in the stereo mix, the song was recorded with Wyman’s vocal in one channel and the instruments largely in the other, with a fluttery reverb on the voice that was likely intended to give it a psychedelic twinge but instead makes it sound amateurishly recorded. Ronnie Lane and Steve Marriott of the Small Faces, who’d been recording in another studio in the facility, contribute background voices but even they can’t keep it from floating away on a cloud of marshmallow. Inexplicably issued as the first single from the album, “In Another Land” went nowhere near the charts.

Things pick up quickly with “2000 Man,” the first of two songs on the album whose title begins with that number. (How far away the year 2000 seemed in 1967!) With Richards playing both acoustic and electric guitars, Jones on the electric dulcimer and Hopkins filling in tastefully on piano, Jagger gives a mostly reserved performance on future-shock verses like “Well my wife still respects me, I really misused her/I am having an affair with the random computer,” then revs it up in the chorus: “Oh daddy, proud of your planet/Oh mummy, proud of your sun,” repeated perhaps a few too many times.

“Sing This All Together (See What Happens),” which ends the album’s original first side, isn’t so much a reprise of the opener as an eight-minute excursion into psychedelic experimentation unlike anything the Stones had done before (even the 11-plus-minute “Going Home” jam on Aftermath). It starts with an out-of-nowhere cough (followed soon after by a voice asking, “Where’s that joint?”), gives Jones about 20 seconds of Mellotron time, then heads directly into several minutes of spacing out, some of it quite aimless, other parts kind of engaging. With all sort of percussion, Jones playing the vibes and everyone else apparently just bashing along on whatever the studio had on hand, it proved that the Stones could improvise just like those emerging California bands, but suggested that they might not want to.

Flipping the album over, side two begins with “She’s a Rainbow,” a song that surely served to give credence to the idea that the Stones were attempting to fashion their own Sgt. Pepper. About 20 seconds of a carnival barker shouting unintelligibly gives way to a stunning Hopkins piano lead and, soon enough, the fully rockin’ Stones—and Jagger’s best vocal on the set. He sings: “Have you seen her all in gold/Like a queen in days of old?/She shoots colors all around, like a sunset going down/Have you seen a lady fairer?” Whether the chorus—“She comes in colors everywhere, she combs her hair, she’s like a rainbow”—is meant to be a double entendre is for the individual to determine, but in any case it’s one of the highlights of Satanic, and the only track from it to score as a single, reaching #25 in Billboard.

(Trivia note: The song’s string arrangement was created by one John Paul Jones, who would emerge a couple of years later as the bass player for some obscure little band called Led Zeppelin.)

“The Lantern,” the next track, is a pretty semi-ballad whose instrumentation is largely, again, given its coloring by Brian Jones, playing organ, horns and bells on the track, and by Hopkins, who keeps things moving at a clip. With full psychedelic effects given extra weight, and Richards trying out contrasting fuzzy and flighty tones on his guitars, the recording takes on a nearly baroque sensitivity. Jagger, too, takes advantage of the freeness, pushing the limits of his range as he gives body to words like “Free from the spell of fright, your cloak it is a spirit shroud/You’ll wake me in my sleeping hours, like a cloud/So, please, carry the lantern high.”

“Gomper” is one of the least memorable tracks on Satanic. Despite some creative journeying into Eastern modes (was Jones already checking out those Pipes of Pan at Joujouka?), not unlike Pepper’s “Within You, Without You,” the song doesn’t go much of anywhere. Jones’ use of recorder and electric dulcimer makes for some unusual textures—unusual, that is for a Rolling Stones album—and Watts’ switching from his kit to the tablas is a rare treat, but ultimately it’s easily forgotten.

“2000 Light Years From Home,” one of the songs (along with “…Rainbow”) that they would later acknowledge by adding it to their live setlist, is another story. This one manages to get its psych on while still summoning the power one expects from a Stones number. With a young Eddie Kramer, an engineer/producer then making his name with the likes of Hendrix, playing the percussion instrument the claves, Jones bringing his Mellotron center stage, Richards going for a roomful of guitar sounds and the rhythm section particularly on fire, the song would just as easily have been a good fit on Between the Buttons but stands as a centerpiece of this album. Jagger, again, seems quite comfortable with lyrics of a less earthy nature than he’s used to: “Bell flight fourteen you now can land/Seen you on Aldebaran, safe on the green desert sand/It’s so very lonely, you’re two thousand light years from home.”

Then, to wrap things up, there’s “On With the Show,” a little slice of oddball psyche-vaudeville-delia that would seem to exist for the sheer purpose of rivaling the role played by the reprise of the title track on Pepper. With more carnival-like chatter leading the way, Jagger soon grabs hold of the nearest megaphone, letting us all know that he wishes it were he who had sung “Winchester Cathedral.” It’s a cheerful little trifle, admittedly, but also rather limp: “You’re all such lovely people dancing gaily round the floor/But if you have to fight, please take your trouble out the door/For now I say with sorrow, until this time tomorrow/We’ll bid you all a fond adieu/On with the show, good health to you.”

And to you as well, Sir Mick.

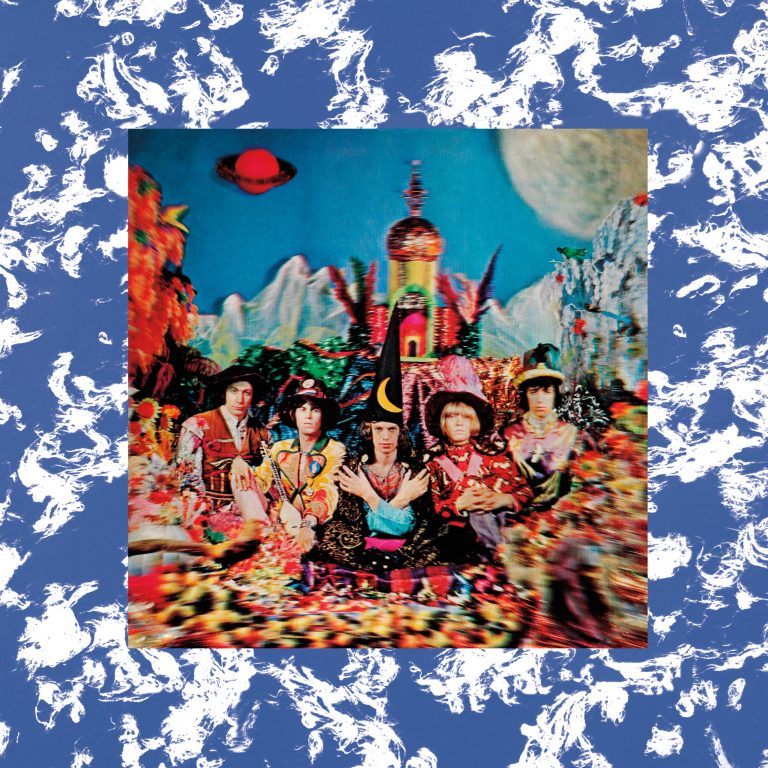

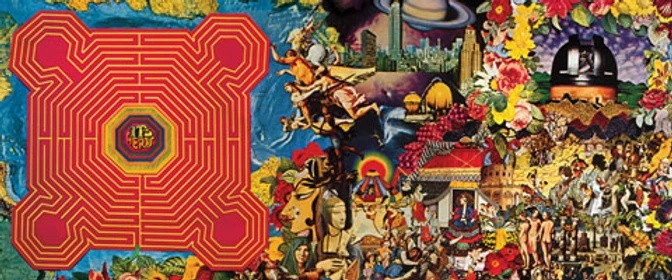

Regardless of how one felt about the 45 minutes of music comprising Their Satantic Majesties Request (whose title was a play on the phrase appearing inside of a British passport, “Her Britannic Majesties Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Requests and Requires…”), there was, at least, the album cover to look at. It was quite cool, most rock fans immediately concluded, even if it was—however one considered the music—pretty obviously an attempt to mimic what the Beatles had done with Sgt. Pepper. Just as the Beatles had commissioned a colossal, eye-popping collage featuring the band in its Pepper finery, surrounded by all manner of foliage, assorted knick-knacks and a host of history’s and the contemporary world’s most notable, notorious and in some cases obscure figures, the Stones went 3-D with theirs.

In fact, the Stones even used photographer Michael Cooper for their portrait, who had done the Pepper cover. Decked out in ultra-colorful ’67 duds, including very groovy hats, the group also trucked in loads of flowers, and threw in a couple of planets, a mountain and a castle and—not that hard to find if you look for a few seconds—the faces of the four Beatles (who had paid homage to the Stones on the Pepper cover, on which a doll wears a shirt proclaiming “Welcome the Rolling Stones”). That assembled, they had it had it shot with a rare 3D camera. The so-called lenticular image allowed the viewer to see the photos “move” when the cover was tilted. A wild and trippy collage was spread across the inside of the gatefold album cover, outmaneuvering the Beatles, who had merely placed the album’s lyrics and another photo inside of theirs.

Watch the Stones perform “2000 Light Years From Home” at Glastonbury in 2013

Was Their Satanic Majesties Request a failed experiment? That’s a good question, and one that each listener must answer. It is certainly unique within their canon—the Stones never made another psychedelic album, that much is for sure. Whether they quickly realized it just wasn’t for them or they got caught up in other trending waves, they returned in 1968 with Beggars Banquet, a much earthier, back-to-basics effort. No one with a pair of ears could possibly compare this one to the Beatles’ White Album (starkly adorned album covers aside).

If anything, Beggars Banquet paralleled another development, taking off in America, that found artists like Bob Dylan, the Byrds and the Band eschewing the excesses of kaleidoscopic psychedelia and looking toward country and rootsy blues music for inspiration. Of course, Beggars Banquet did include incendiary tracks like “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Street Fighting Man” alongside its more chill “Stray Cat Blues,” “No Expectations” and “Salt of the Earth,” and no one else was going there quite the way they were–yet.

Related: Our Album Rewind of the Stones’ Let It Bleed

If, for a few minutes, the Rolling Stones truly had been trying to out-Beatle the Beatles, they didn’t stay in that place very long. And, of course, while their pals were packing it in by 1970, the Stones were, in some ways, just getting started. Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main St., anyone?

Watch the Stones perform “She’s a Rainbow” in Paris in 2017

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

7 Comments

I always loved this psychedelic album. It has a lot of hidden gems on it. You have 2000 man, She’s a Rainbow, 2000 Light Years From Home, Citadel and the Gomper. Brian Jones influences are all over this album. The original album cover was in 3D which made this album even more psychedelic. I have the original album still sealed.

love this album maybe my favorite stones album. maybe if you consider in another land an acid trip. it opened his eyes when he awoke. saw the world differently. not a goof at all

It has two classic tracks: She’s A Rainbow and 2000 Light Years From Home. Two good tracks: Citadel and 2000 Man. Unlike many others i have always liked Bill Wyman’s In Another Land. Others should have been throw away in the studio’s dustbin!

Selected gems alongside a load of garbage.

We Love You and 2000 Light Years are the two timeless classics.

2000 Light Years is extremely precious for having Brian and Keith playing together so well, Brian on lead with mellotron, Keith supporting w rhythm guitar riffing.

It was like.

Sargent Peppers-Strawberry fields acid.

Satanic Majesties-Brown acid.

I liked SMR when it was released but like you said, what they did after that was just so much better. Not a bad album though.

I absolutely love this album! Perfect for its time!

By all accounts “Pepper” and “Majesties” were recorded concurrently in separate locations. The Beatles being the more focused group, got theirs out first.

“Focus” being the operative word, “Pepper” succeeds (unless you’re Richard Goldstein) as a cohesive work, while “Majesties” is your typical Stones LP – a few great songs, and the rest . . .

I remember playing pinball in my local bowling alley in the late 60s. And one of the songs that was always on the music system was “2000 Light Years from Home”. Apparently, London issued a jukebox EP of “Majesties”. Always been one of my favorite Stones songs.