Can you name an American singer-songwriter born in a small town in 1941, who started out in the traditional folk idiom in the early ’60s, found fame in the big city, began writing his own material, “went electric,” settled into what is today called Americana and is still going strong?

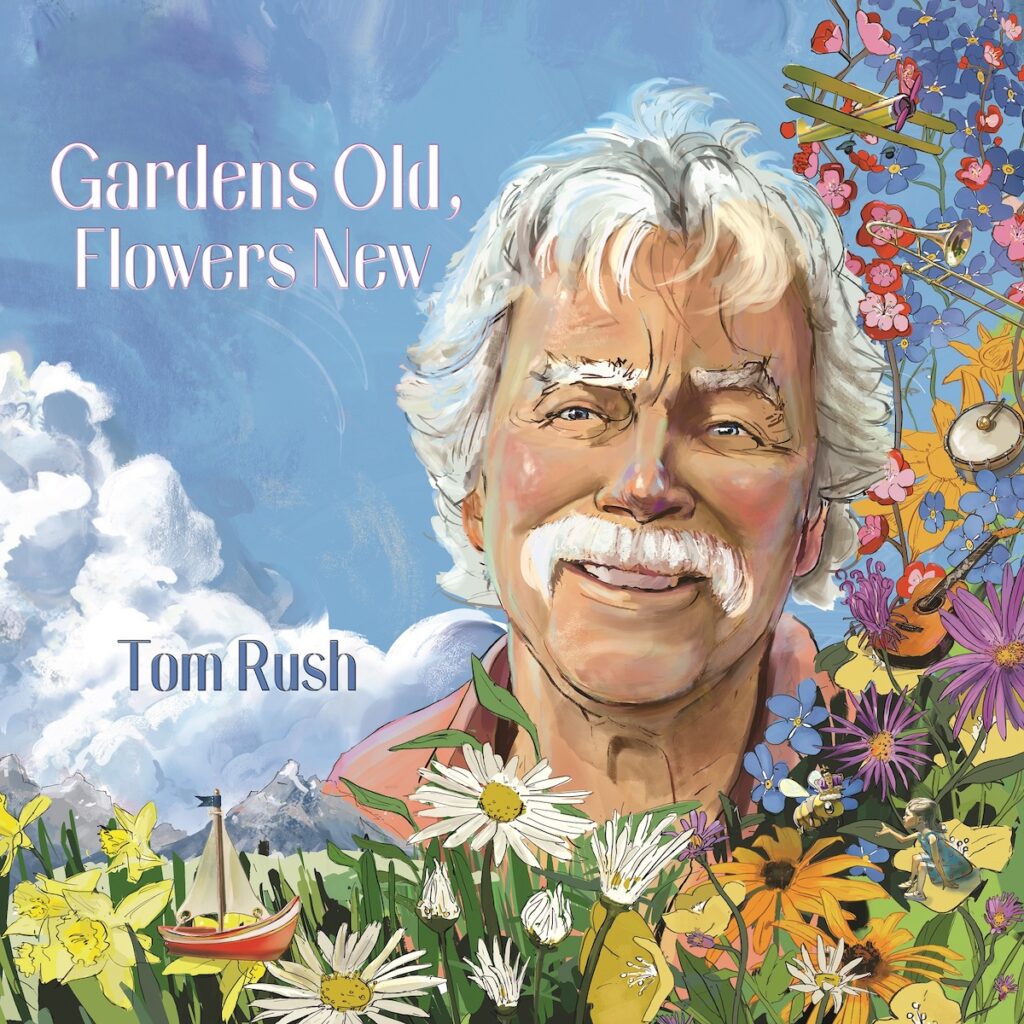

Of course you can! His name is Tom Rush, and he has a brand new album that’s the equal of any he made for Prestige, Elektra and Columbia in the formative part of his career. It’s titled Gardens Old, Flowers New, produced by Matt Nakoa, a young multitasker who’d never heard of Tom Rush before he was hired to play keyboards for a concert by the latter in Boston 10 years ago. Nakoa not only produced the new recording, but served as Rush’s primary accompanist. “If this was 50 years ago, he would be playing stadiums. He’s an amazing talent,” says Rush. “He’s a fucking genius. That’s the technical term.”

Rush says he prefers recording in the old-school manner: musicians and singers creating the music together in the same room simultaneously, rather than piecing it together with individual parts emailed in from far and wide. Thus, 2024’s Gardens Old, Flowers New was recorded in an old barn in Connecticut. “I like a studio,” Rush says. “And I like other people to be responsible for all the tech stuff. I learned a while ago that I’m good at it, but you can’t, at least I can’t, wear two hats at once. I can’t be the engineer and the artist. It’s left brain, right brain. The left brain really gets in the way of doing the creative stuff, in my personal experience. This old barn was turned into a very up-to-date studio, which I enjoyed. And there were some bedrooms upstairs, so we didn’t have to go check into a hotel every night. It was very cool.”

The songs for the album, Rush says, were largely finished before he began working on it. He hadn’t been thinking about assembling them into an album, but once that notion germinated, he knew it was time to make a new statement. All of the tunes on Gardens Old, Flowers New were written by Rush, with one, “Glory Road,” dating back to 1973. Another, “Gimme Some of It,” is based on a traditional blues called “Custard Pie,” with new lyrics by Rush.

“They seemed to flow from one to another,” says Rush of the album tracks. “The third from the last song, ‘To See My Baby Smile,’ is about breaking up with my wife. And that’s pretty sad. But then the next one [“Won’t Be Back at All”] is a little bit cheerier and the last song on the album, called ‘I Quit,’ is kind of upbeat. Everybody seems to have a different favorite, which I guess is a good thing.”

The album title was chosen, says Rush, because that phrase turns up in two different songs on the album. “It’s kind of coincidental,” Rush says. “Matt made the point that I’m not a spring chicken. I’m the old garden and I’m coming up with new flowers.”

Watch Rush and Matt Nakoa perform “Glory Road,” a song from Gardens Old, Flowers New

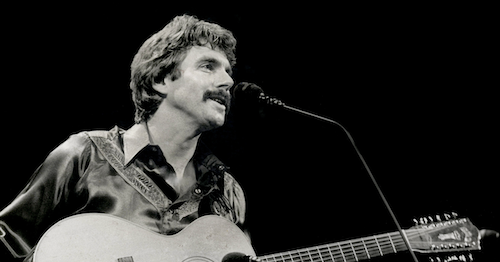

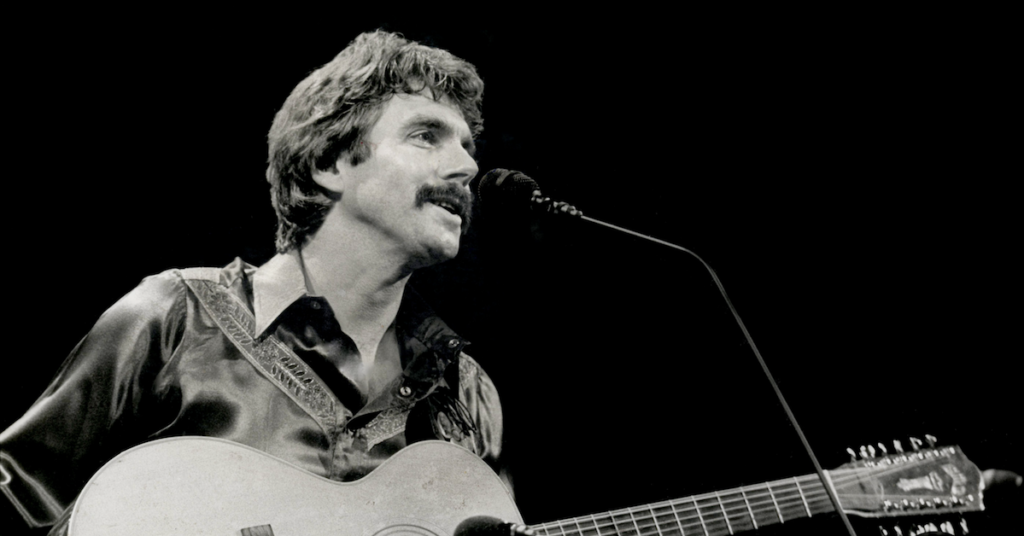

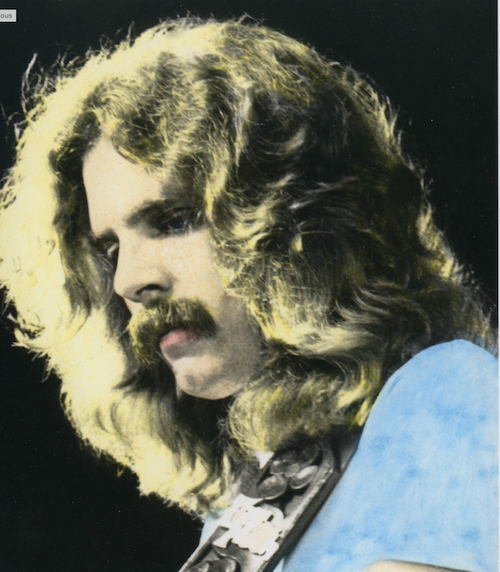

Tom Rush, originally from New Hampshire, has been making music since his teens and early twenties, semi-professionally at first as he attended Harvard University. He released his debut album, a live set called Tom Rush at the Unicorn, in 1962, and has followed that up with nearly 20 more studio and live albums, releasing new music in every decade except the ’90s. His ’60s albums for Elektra Records—a self-titled 1965 effort, 1966’s Take a Little Walk With Me and ’68’s The Circle Game—are considered classics of the genre. The latter is noteworthy for its songs written by Joni Mitchell (including “Urge for Going,” which became a staple of Rush’s repertoire, along with the title track), James Taylor and Jackson Browne before most listeners had heard of any of them. That same album included “No Regrets,” perhaps the song most closely associated with Rush.

“I was accused by Rolling Stone of ushering in the singer-songwriter era,” Rush says with a laugh. “I wasn’t trying to usher in anything. I just wanted to meet girls!”

Moving to Columbia Records in the early ’70s, Rush enjoyed more widespread popularity with albums like Wrong End of the Rainbow, Merrimack County and Ladies Love Outlaws. Since then he’s recorded for independent labels, including Appleseed Recordings, his current home—Gardens Old, Flowers New is his third title for that label.

Best Classic Bands spoke with Tom Rush about his lengthy career—even that time he opened for Alice Cooper…

Best Classic Bands: How has your songwriting process changed over the years?

Tom Rush: I don’t know that it really has. For me, songs have always just kind of happened. In the best of worlds, I sit down first thing in the morning with my guitar, before I’m fully awake, and strum away and try not to really think about anything. I try to catch any ideas before they drift away again. Sometimes they add up to a song and sometimes they don’t. But I’m not good at sitting down and deliberately trying to write a song. I’ve done it a couple of times, with some success.

When you perform live, to this day there are certain songs from early in your career that you have to play, like “The Circle Game” and “No Regrets.” Do they still mean what they meant to you back then?

Well, the good news for me is that having been doing this for some decades now, I can rotate them around. In the autumn, in the winter, I will do Joni Mitchell’s “Urge for Going.” And then come spring I will switch to “Circle Game.” Two brilliant songs, but one [“Urge for Going”] is seasonally specific. I actually went for years without doing “No Regrets.”

“No Regrets” is the quintessential Tom Rush song and it’s been covered by so many artists.

I know. I just learned that Harry Belafonte recorded it. George Hamilton did it, McKendree Spring. Lee Hazlewood, Waylon Jennings, Olivia Newton-John, Emmylou Harris, Shirley Bassey. She had a huge hit with it in England. And Midge Ure, of Ultravox. And then a band called Quartzlock did a hip-hop version that I didn’t recognize when somebody played it for me. U2 also recorded “No Regrets.” It was only the chorus.

Watch Tom Rush perform “No Regrets” live in 1976

You were one of the first artists to recognize Joni, James and Jackson.

I think the fact that these three brilliant writers were all introduced on one project got people’s attention. I pitched Joni to Jac Holzman at Elektra and he said, “No, she sounds too much like Judy Collins.” And she did sound a lot like Judy; Judy was a big influence on her. But come on, Jac. Listen to the songs. Anyway, he didn’t go for it.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Jackson Browne’s debut LP

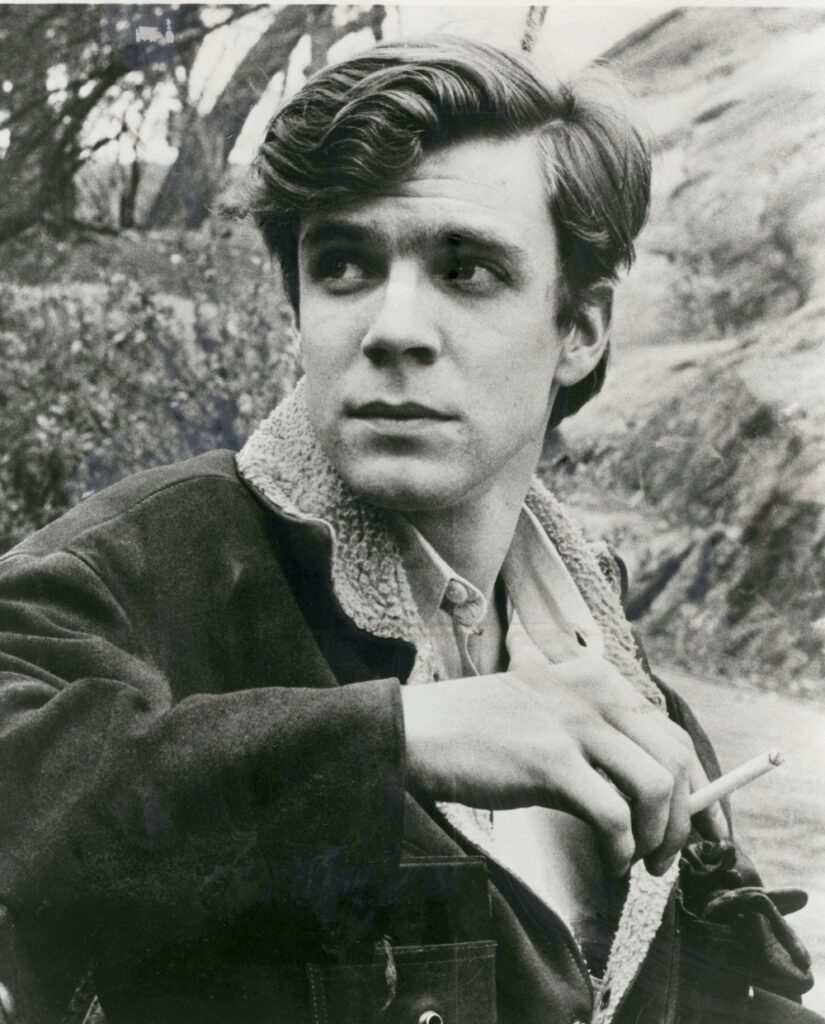

Most people don’t realize that you had already released three albums before you signed with Elektra, more in the pure folk vein.

I did. My first album was At the Unicorn. The Unicorn was this little club in a basement on Boylston Street in Boston. I had a regular gig there and this guy came down the steps and said, “Do you wanna make an album?” I’d heard that before and nothing had ever come of it. So I said, “Yeah, sure.” He dragged this tape recorder the size of an oven right down the steps and recorded two nights, a week apart. I remember him telling me it was morally indefensible, a horrible thing, to intersplice. In other words, to take the first half of the song from night one and the second half from night two. You mustn’t do that. I later learned it was because he didn’t know how to edit tape. But he made that into an LP [in 1962] and distributed it out of the backseat of his Studebaker. I think we sold a total of maybe 600 copies, probably more like 300. I still see them on eBay going for a few hundred bucks apiece. Anyway, that was my first one and it was actually a turning point for me. I don’t think it was that good, but I was the only one in the crowd that had an album out. Somehow that made me more legitimate. Then, not Elektra, but Vanguard and Prestige, came to town and started signing everybody up except me. I was the one that was left out for a couple of years, and then [producer] Paul Rothchild finally came to his senses and hired me to do an album for Prestige. We did the first one [Got a Mind to Ramble, 1964] and I guess it did okay. Prestige was a jazz label, but then they became a folk label. Then Paul left and went over to Elektra. I wanted to go to Elektra with him and Jac Holzman wanted me to come to Elektra. But I owed another album to Prestige. Basically, I said, “Hey, I’m a Harvard student. I don’t need this crap. I’m gonna become a lawyer or something.” And they fell for it. I said, “The only way I’m gonna make a new album for you is that Paul Rothchild will produce it.” They laughed and they said, “Holzman will never allow that,” but Holzman did, because he wanted me to come over. So we recorded the second Prestige album [Blues, Songs & Ballads, 1965], I think in an afternoon, and it was good. It was traditional folk and it was just me. The next week, we went into a studio with some sidemen. It was called Tom Rush [Elektra, 1965] . Felix Pappalardi was there. John Sebastian told me it was his second paid gig ever. Prestige did not realize there was a race going on, but Elektra got theirs out before Prestige did.

You started using sidemen on your self-titled 1965 album for Elektra, around the same time that Dylan plugged in. Did you sense that there was a major change happening in music?

Yeah, that was definitely a shift, and a good one. And Paul Rothchild did a great job assembling the sidemen and making it all work. We did the same on the next, Take a Little Walk with Me. One side of the album was kind of traditional folky and the other side was basically rock and roll stuff.

Take a Little Walk With Me had musicians like Al Kooper, Harvey Brooks and Bruce Langhorne on it. How did that switch to rock and roll come about?

I really got into music listening in the ’50s to rock and roll, when I was a kid. I wanted to be Elvis and all those guys. It only lasted about four years and then the [rock and roll] revival happened about 10 years later. It was love for the music, plus I needed to get an album out and I didn’t have any more of the folky stuff that I was interested in. So I did this kind of schizophrenic project. And then The Circle Game was very orchestral, which was really a departure for me. It was an important step in the right direction for me, but I never got orchestral again.

Listen to “You Can’t Tell a Book By the Cover” from Take a Little Walk With Me

What was it like working with Jac Holzman?

He was a great guy. His book, Follow the Music, is a good book about how things were working back then. If any of the artists had a problem, they could go talk to the boss. It wasn’t this huge corporate structure. And he really did focus on trying to enable me and my colleagues to make the best work we could, and not get in the way.

What do you remember most about your early days in Cambridge, while you were attending Harvard?

I wanted to be a marine biologist. I had a biology teacher at Groton School [a prep school in Massachusetts] who was a superstar in my eyes and I loved skin diving, so I said, okay, marine biology. I was accepted at Harvard, Princeton and the University of North Carolina. North Carolina has a really great marine biology department. My dad taught at St. Paul’s School [in New Hampshire] and advised thousands of students on which colleges to apply to. But when it came to me, he said, “No, Tom, it’s your life, it’s your decision.” He wouldn’t get involved. So I finally said, “Okay, Dad, I’ve decided. I’m gonna go to University of North Carolina.” And there was a prolonged silence. And he finally, at the 11th hour, 59th minute, said, “You’re going to Harvard.” He’d gone there and his father had gone there and he thought it was all about connections: You meet all these people that are important later in life. Which actually happened in the musical world, but not in the academic world. So I ended up in Cambridge and there was this huge folk thing going on. It’s all very traditionally oriented. I was told, “We want people who built their own instruments and can’t read and live in a cabin somewhere in the woods.” It was a little ironic having all these Harvard students sitting around singing about how tough it was in the chain gang. But we figured we could make up with sincerity what we lacked in authenticity.

After your run with Elektra ended, you jumped over to Columbia. How do you feel about the recordings that you made there?

I think they all came out well. The last one, Ladies Love Outlaws, was a departure. It might not look that way from the outside, but it was a very different thing, much more professionally oriented. I don’t mean in a positive way. I remember their studio crews were all union. You’d rehearse the song and get the first couple of takes and now was gonna be the perfect take and they would go on a coffee break. So I actually went to Canada to make one of the albums, and did another one, Merrimack County, from my home in New Hampshire, so that I wouldn’t have to deal with the union guys at Studio B. I think they actually put up a billboard for me once in Los Angeles, which is kind of weird.

You were involved with the Festival Express, the 1970 train tour across Canada that featured the Band, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin and others. You’re not in the movie though. Did you actually perform?

I did play it. I clearly was not one of the superstars. But it was the best party I’ve ever been to.

The stories about that trip are epic, like stopping off in some little town in Manitoba and buying out the liquor store.

Yeah. Every single bottle. We came to regard the concerts as kind of an unwelcome interruption in the partying. There was some talk about buying the train at the end of it and parking it somewhere and just partying on until the money ran out and then we’d go do a show somewhere to replenish the bank account. Didn’t happen.

Listen to Rush sing Jackson Browne’s “These Days”

After you left Columbia, what happened?

Unfortunately, I made a career mistake. My contract with Columbia was up after the third album. I said, “I’m gonna go over to Asylum [Records].” And Columbia said, “No, no, no, no. We’ll sue.” I hired a lawyer, who later turned out to be working for Columbia. They finally offered me a contract. I actually went through it page by page and it was inferior in every way to the original. I called them on that and they came up with a contract that was better. I should have left. I should have just said, “Nope, I’m gone.” But I didn’t, and I stayed and I made Ladies Love Outlaws, which did not sell. They assigned me a producer and their whole thing was, okay, we gotta get this guy to appeal to the masses better. And it didn’t work. It kinda pissed off my crowd because it wasn’t the good old Tom Rush they were interested in. So then they dropped my contract, and I was out on the street, having been dropped instead of having left under my own will. I couldn’t get another major label contract at that point because I had this stain on me. So I just didn’t make another record for quite a while. I finally decided I’m doing shows at Symphony Hall Boston. I’ll record them and put them out as live albums on my own label. I like them, but I didn’t have the smarts or the apparatus to promote them. And then, Jim Musselman [of Appleseed Records] persuaded me that I really should make an album that was gonna be distributed. And I’m glad he did. The first one was What I Know. Voices was the second one, which is the first album where I wrote all the songs except for two traditional songs.

A video of you performing a song called “The Remember Song” [written by Steven Walters] has gone viral on YouTube with over seven million views. What’s the story behind that?

It was a funny thing. I think Gene Shay, a folk DJ in Philly, sent it to me. I was a guest for Judy Collins in San Diego, an outdoor show. They videotaped the whole show. Arlo [Guthrie] and Eric Andersen and I were basically the opening acts. We shared the first half of the show and Judy did the second half. The contract gave me access to the videotapes. I was doing shows under the name Club 47, where I would have another artist who was established, and a couple of newcomers and we’d all mix it up. Judy was my guest on some of those shows, and she decided that that was a good format, except she didn’t want to mix it up with anybody. She just wanted the second half of the show herself. She did several of ’em. This one was videotaped and I sent the tape of “The Remember Song” to my webmaster, saying, “Post it. Who knows, maybe somebody will like it.” And it kind of took off. My daughter insists that the seven and a half million plays are probably just one guy who can’t remember he’s already seen it.

You also host a video series called Rockport Sundays? What’s that about?

Covid hit me pretty good. All the shows that year, 2020, were being canceled. Number one, I love playing for people and number two, I love getting paid for it. What am I gonna do here? I decided that maybe I should do something online, a subscription series. We’ve developed quite a following. Sometimes it’s just me, but almost always I’ve got a guest. I’ve got a studio here up above the garage. The production values are pretty high. It’s not slick. The whole idea is to be casual and informal and talk about stuff that we don’t usually talk about. And then we each play a song and it’s, “Thank you for coming and see you next week.” I’ve had Jonathan Edwards and Tom Paxton and Jim Kweskin and James Montgomery. Been doing it for three years now. It’s a lot of fun making them. It’s not quite like playing for a live audience. I’ve learned that when you tell a joke to a video camera, it doesn’t laugh. You get used to that. I was thinking actually of putting in a laugh track, just on one episode.

You’ve never considered retiring. A lot of your contemporaries have.

I was talking with Tom Paxton about retirement and his comment was, “What would I do? Sit around and play the guitar all day?” Might as well have fun doing it and get paid.

You once shared a bill with Alice Cooper. A lot of potential for calamity there!

Oh, that one. This show with Cooper was one of many odd combinations. I once had a co-bill with Martha and the Vandellas, in Boston, way back when. If I’m remembering right, it [the Cooper double bill] was an outdoor show. I was opening the show and it was clearly a mismatch. I had some fans in the audience, but he had more. I’m playing along, trying my best to engage the audience, but it’s nighttime, and all of a sudden there’s a skydiver coming down. All the lights that were on me a minute ago are in the sky on this guy with a parachute, blinding him. He can’t see where he is going anymore. He comes floating down and there’s this chain link fence about 20 yards to my right, and the poor guy comes down and straddles that fence, screaming. It’s hard to engage an audience when that’s going on.

Watch Tom Rush perform “Urge for Going” in 2010

Rush’s 2024 release, Gardens Old, Flowers New—as well as his extensive recorded output—is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. Go see him perform! Tickets are available here.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024