You already know everything that happens in this movie and you’ve seen most of the footage. Yet Eight Days a Week—The Touring Years, director Ron Howard’s Beatles documentary – that opened in theaters on September 16, 2016, and is available for streaming and on DVD and Blu-ray – is so thoroughly engaging that you won’t mind at all.

Eight Days a Week doesn’t endeavor to tell the entire story—The Beatles Anthology did that more than adequately in the 1990s. There’s black-and-white footage of children playing in bombed-out post-WWII Liverpool lots, familiar photographs of the young Quarrymen and that grainy “Some Other Guy” clip, but those only serve as reference points. So too do the Beatles’ last few, studio-only years—this film isn’t about that: The doc hastily dismisses Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, the White Album and Abbey Road, brushing them out of the way to get to that moment of finality on a frigid Savile Row rooftop.

That scene, the four braving the London winter chill in their oversized coats, is essential—it marked the Beatles’ last semi-public appearance as a performing unit—but it too is only here because it must be: By the time it takes place, in January 1969, the Beatles have long since distanced themselves from the shrieking pubescents who only a half-decade earlier had made four young men a worldwide phenomenon and then made them miserable. The rooftop lark—“Don’t Let Me Down” and “I’ve Got a Feeling”—comes shortly before the closing credits roll; Howard is more interested in the way up than the inevitable crash.

And so Eight Days a Week is a nonstop rush of adrenaline, a comfort-food feast of melodic guitars and impeccable harmonies, unbridled creativity and boundless artistic determination, cheeky wit and newness and wonder and youth.

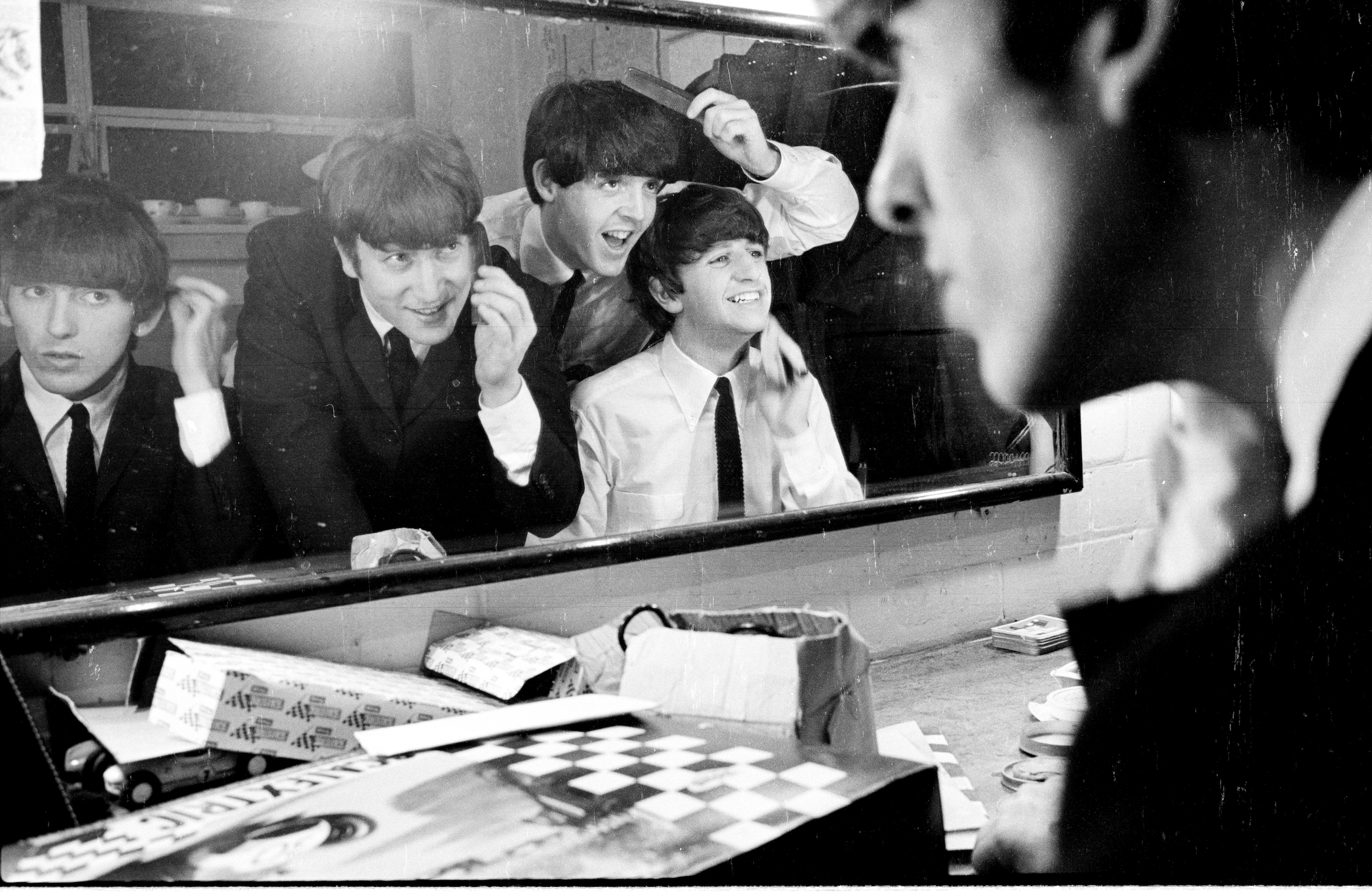

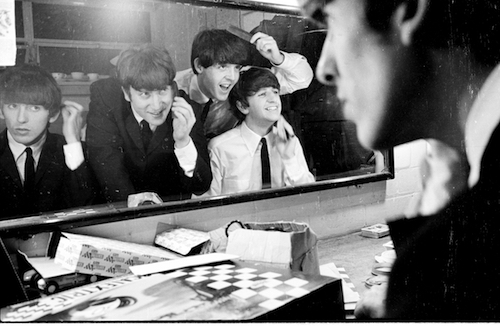

And screams—lots of screams. It’s a constant jolt of electricity—each time we see them launch into a song before those squealing, crying, jumping, never-happier-in-their-lives children who loved them so dearly and couldn’t hear a note they played and couldn’t have cared less, each time the “four-headed monster,” as Paul McCartney calls them, put their heads together on a single mic, each time we see their own disbelief that this is happening to them, we experience what the film calls “the epidemic of Beatlemania” all over again.

If you were too young when it happened, or not yet in existence, you’ll come away understanding why we boomers all acted the way we did. You can’t watch this film and not.

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

Eight Days a Week doesn’t begin in America, although for so many here it seemed as if the world suddenly sprang to life when these strange visitors from another planet landed at JFK. The Beatles were already massive stars at home by that time, a once grungy but now spiffed-up little rock ’n’ roll combo that had, against all odds, worked its way up from the scummy basements of Liverpool and the even scummier dives of Hamburg to the “toppermost of the poppermost,” as John Lennon called their holy grail.

The Beatles had been worried that America wouldn’t get them. They didn’t want to come over here until they had a #1 record. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” entered the Billboard Hot 100 on January 18. Two weeks later it was #1. They arrived on February 7, played Ed Sullivan on the 9th and owned the Top 5 on April 4.

It was the addition of Ringo Starr back in 1962 that had been the turning point, says McCartney. “When Ringo joined we looked at each other and said, “This is it,’” he claims in contemporary interview footage. Soon there were mile-long queues, hysteria, fainting. “Why do they scream?” Lennon is asked. “I couldn’t tell you,” he replies.

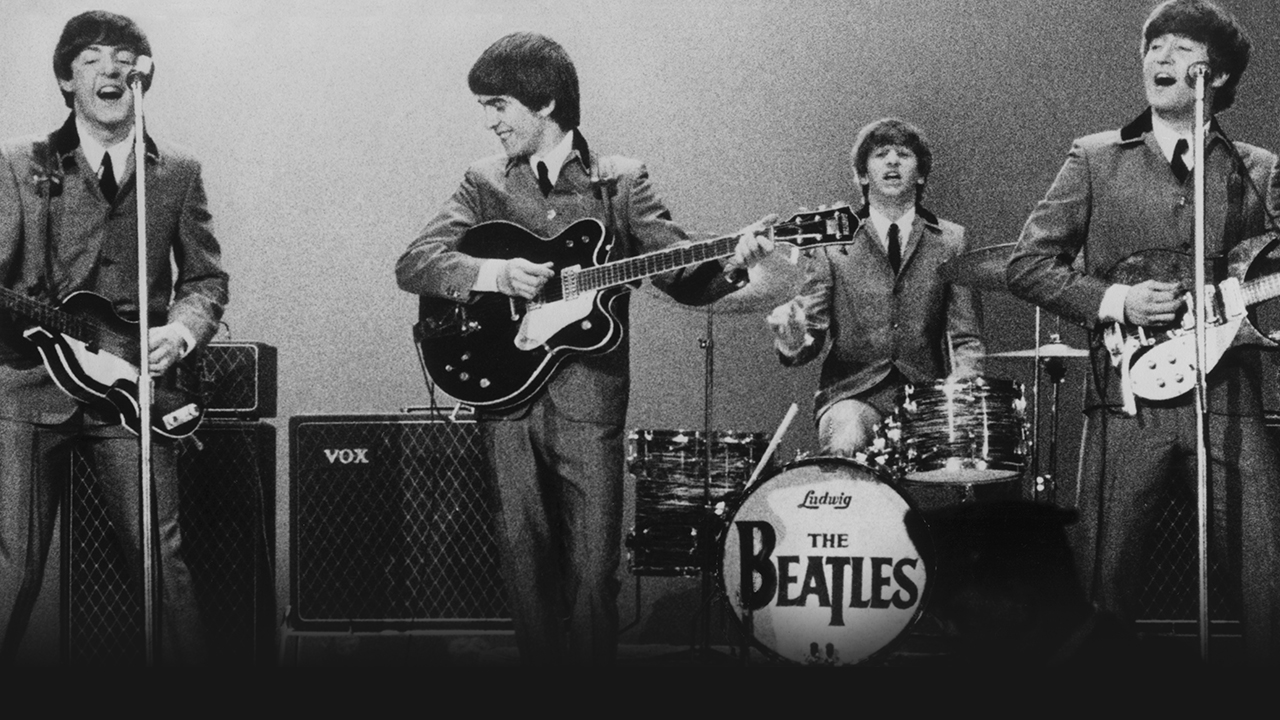

But we know why. The answer is in every “She Loves You” and “I Saw Her Standing There” and “Roll Over Beethoven” they churn out. It’s in the music and the presentation of that music. It’s in the moves and the matching suits and, yes, the moptops. It transcends language—the fans are just as besotted in Paris and Copenhagen. Many naysayers have theorized that the Beatles were not even very good live. Eight Days a Week eviscerates that lie. When we can hear what they were actually playing—and with the remastered sound, courtesy of producer Giles Martin (son of George), we can—they were, undeniably, quite spectacular.

We’re reminded, constantly, that with the Beatles it always came down to the songs. Paul estimates he and John wrote about 300 of them, and notes that George became a rather excellent writer himself. A musicologist compares them to Mozart—not since the classical dude’s heyday did any single entity compose so many quality songs, he says. But we’re also reminded that how the Beatles played those songs is as much the reason for their greatness as the songs themselves. We see them inventing—there’s a goodly amount of studio footage too—but Howard’s point is that something else took over when they walked out onto a stage.

Admittedly, it’s their seemingly overnight rise in the United States that makes the story what it is though. Had they never broken out of England, well, who even wants to think about that? “We could feel we were in New York before landing,” Lennon says in the film, and New York had already felt them—the pandemonium of their invasion, and it truly was that, was something that had never before occurred and never would, or could, again. We watch it unfold; we see their effect. When Whoopi Goldberg says, “The whole world lit up” for her, we know what she means. It lit up for everyone who came under their spell.

Related: The Beatles’ 1965 Shea Stadium concert

Eight Days a Week, which does include a decent amount of rare and previously unseen footage, some contributed by fans, is concerned, primarily, with those three years of 1964-66, when the Beatles remade the world. At one point the young McCartney is asked about the range of the Beatles’ cultural impact. He looks back at his interrogator as if he’s daft. “It’s not culture, it’s a good laugh,” he says. He could not yet have known that he and his mates were indeed redrawing the cultural map.

Howard—an Academy Award-winning director for A Beautiful Mind and a popular child actor when the Beatles first arrived—hits most of the touchstones: the importance of manager Brian Epstein (although his death goes unmentioned); the frantic press conferences and photo shoots and all that running around and running away; the making of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!; the natural evolution toward Rubber Soul and Revolver; their introduction to marijuana (but, curiously, not LSD). We see the fans, like Adrian from Brooklyn, who wants Paul to know that she will always love him, and the girls who’ve studied George’s “sexy eyelashes.” We hear from the late producer George Martin and Liverpool lad Elvis Costello and Larry Kane, the only American journalist allowed to tour with the band. Sigourney Weaver tells us what it was like to be in that crowd screaming her lungs out.

Through it all the camaraderie remains intact. “We felt sorry for Elvis,” Harrison says in his later years, “because Elvis was only one person.” The Beatles, as four, had each other. All decisions had to be ratified by the entire group. But they too ultimately recognized that they were individuals. They started families, pursued their own interests. Being Beatles, they discovered, was not all there was. Within a couple of years, these wild-eyed young musicians had not only risen to the top of their field but become international icons. It was a lark, they keep telling us.

But they’d also become prisoners of their fame. If they weren’t caged in a hotel room they were being hounded by fans literally wanting a piece of them. These same foreigners who had managed to introduce integration to a Florida venue became the targets of a “Ban the Beatles” record burning after John declared they were “more popular than Jesus.” There were riots and bomb scares; kids were getting hurt; government officials and police officers, in America and abroad, were blaming them for this, that and the other. We were still having a blast; the Beatles weren’t.

Related: The Beatles’ Live at the Hollywood Bowl album gets expanded release

As early as 1965 they were tiring of the circus of live performance; by the summer of ’66 they’d agreed to give it up. What good was it playing in front of 50,000 kids when the screams drowned out the sound so thoroughly? Not only could the audience not hear the music—amplified through crap house PA systems—but neither could the band: Stage monitors as we know them today didn’t exist yet. Ringo claims in the film that he had to watch Paul from behind just to get an idea of where in a given song the others might be.

The studio gave them solace. To go from creating songs like “Norwegian Wood” and “Girl” to rehashing “She Loves You” in stadiums seemed ludicrous to them. George Harrison was the first to say he was done with the road. After Candlestick Park in San Francisco, in August 1966, he made his decision. The others didn’t argue. With that great relief having set in, they set their sights on studio experimentation. “Strawberry Fields Forever” and Sgt. Pepper would soon arrive.

With Eight Days a Week’s fine focus on the touring years it’s easy to understand why the Beatles wanted to quit the road and eventually quit being Beatles. But Howard also allows us to embrace the solidarity they felt during their eight years together, what McCartney calls “being in our own heads.” A film, even one this good, can give us a glimpse inside of those heads and those lives but it reminds us that only they were the Beatles; nobody else was. Only they knew what that was like.

[The title track reached #1 in the U.S. on March 13, 1965.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

5 Comments

Besides everything else that impressed me when I first saw The Beatles, one thing kind of stood apart as extremely unusual: After each song, they would take a synchronized bow in the traditional theatrical manor. It seemed almost shocking to me, as their entire musical performance looked so informal and wild, then, in nearly robotic fashion… like a single gear-driven machine, they would honor their audience in this most reverent and unusual way (for a rock band).

It still impresses me today, when I see that in these old films. You can imagine, under the direct tutelage of Brian Epstein, they must have rehearsed that singular motion endlessly, until it was just a reflex for them. It’s easy to say that this is just one more thing that made them the most amazing band ever!

good work, jeff! as a life long fan(well,since ’63), i can see the beatle fan in you.

The movie should have been longer and better. There are other early shows on film not shown. Ron Howard didn’t even visit Liverpool, only London.

The Rolling Stones actually wore matching suits and ties in 1963 and early 1964 too until their manager had them not wear them anymore and created their exaggerated , so Buddy Holly and The Crickets, The Shadows,The Beech Boys wore shirts with big matching shirts The Moody Blues, and even the blues rock and roll band Eric Burden And The Animals and there are online pictures of them dressed this way.

Because back in the 1950’s and early 1960’s it was common for rock and roll bands to be wearing matching suits and ties to get much better professional live playing jobs. But by the late 1960’s nobody had to do this anymore because everyone were hippies now.

Also the early Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, and even the early Who had screaming teen girls at their early concerts. And one of the many all too common myths is that Brian Epstein created The early Beatles hair cuts.

But it was Jurgen Vollmer who cut their hair that way almost a year before they even met their manager Brian Epstein and Jurgen was one of the first of three intellectual Beatles fans and friends of theirs, they met who would go and see them playing live in the clubs in Hamburg Germany. Jurgen had worn his hair that way since he was a teenager.

In an online August 1971 Rolling Stone Magazine interview with Keith Richards and he said that in the beginning The Rolling Stones had hysterical female fans chasing him down the street like The early Beatles did and he would say to them, What do you want?

He also said they had screaming teenage girls at their early concerts and that there were no monitors back then. He also said that The Beatles are so ******* good at what they did, it’s a shame they broke up in such a tatty way.

There are many pictures online of teen girls screaming at early Rolling Stones concerts in 1964, 1965 and 1966. And also many online pictures of The Rolling Stones on the covers of teen magazines in 1964,1965,1966 and even two in 1967. Some of these teen magazines have both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones on the covers and inside of them together.

Mick Jagger was on the cover twice on the cover of the then leading teen newspaper KYA in 1965 and the December issue says he talks about how his Christmas was ruined. I have all of these pictures on my blog and Pinterest board too.

There is also an online 2019 interview on a site called Nola with two women friends who saw The Rolling Stones in 1966 in Houston when one was 15 almost 16, and the other was 16. And one of them said how cute she thought Keith Richards was back then. And one of their mother’s gave them smelling salt so they wouldn’t faint.

There also used to be an online 2007 interview with Roger Daltry of The Who and he was asked if they had screaming teen girls at their early concerts, and he said after their song Can’t Explain came out they did and he said it was the era of screaming teenage girls and every band had them on their way up.

He said it was the era of the screaming teenage girls and every band had them on their way up but he said the trouble is, is you start to depend on how much they scream which is why The Beatles gave up playing live. He also said that their early manager turned their image from rockers to Mods.

And the live sound systems were very limited and primitive and feedback monitors hadn’t even been invented yet.