To commemorate The Who’s 10th anniversary, the music industry trade magazine Record World published a special section within the pages of its November 23, 1974, issue to celebrate the band. Among the numerous ads from such Who business partners as record labels, booking agents and production companies was a lengthy interview with the band’s guitarist, principal songwriter and occasional lead vocalist, Pete Townshend.

To commemorate The Who’s 10th anniversary, the music industry trade magazine Record World published a special section within the pages of its November 23, 1974, issue to celebrate the band. Among the numerous ads from such Who business partners as record labels, booking agents and production companies was a lengthy interview with the band’s guitarist, principal songwriter and occasional lead vocalist, Pete Townshend.

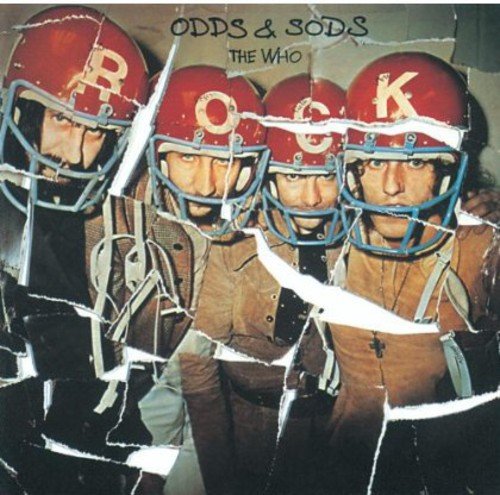

Born May 19, 1945, Townshend was just 29 years-old at the time. To put the timeline in perspective, The Who had released Quadrophenia one year earlier, their Odds & Sods collection had just been released, and the filmed version of the classic rock opera Tommy was in post-production.

From ten years of successful records, what would you select as your most satisfying piece of work?

That’s a very difficult question. Along the line, everything has satisfied me in one way or another. I think the most satisfying thing overall has been Quadrophenia as a piece, because I saw that through from the beginning–the writing, I controlled all that, I did all the recording and the mixing, and looked after the cover. In a funny sort of way, it was the most worrying as well.

Going back to the beginning when you used a fair amount of outside material, what inspired you to start composing for The Who?

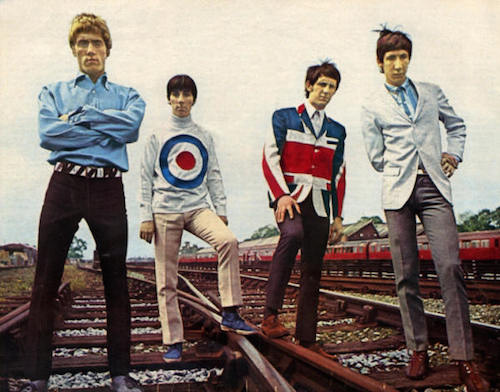

Well, it’s a short, neat story. We were trying to get a recording contract playing rhythm and blues. We used to play lots of Tamla-Motown, and R&B like Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker, material like that, just anything that was good on the stage. We went for our first recording audition, which I think was at Abbey Road. This was for EMI–John Burgess who was head of A&R–and he said, “Well, listen, you’re a great group and we’d love to take you on, but since The Beatles have become a success, we’re only taking on groups that can write their own material.” We went away very disheartened because we thought, well, if we’re a great group why don’t they just take us on?

So they looked around for somebody to write and I, having written one or two songs before, which the group had done on stage (just silly little things), they just said in desperation, “Well, why don’t you have a go?” So I had a go and came up with “I Can’t Explain.”

When The Who started, did you ever envisage that you would enjoy the kind of success that you have achieved?

It’s hard to say because when you’re a snotty-nosed little kid you suffer from two things. One is an inferiority complex and the other is an excessive fantasy. So my inferior side said I was never going to get anywhere or do anything, but in dreamland I always imagined that The Who were going to be the biggest group in the world. It was a bit daunting at one time, about three years into our career, the sheer number of groups there were. I though, Christ almighty, we’re never ever going to get our head above this lot and it was quite remarkable when we first went to America–people were talking about The Who being the number three group in England, which just wasn’t true. There were The Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks were an enormous force then, as a writing force as well, and a lot of my early writing was influenced directly from Ray Davies, who had a four year start on The Who. I can’t remember all their names but there were loads of bands around then who were all very very good. They’ve just fallen by the wayside, leaving The Who there.

Who else do you admire musically?

Just millions of people.

Let’s put it this way. Is there another guitar player you admire?

I like Eric Clapton. I know it’s a bit of a cliche to say that, but I just like the way he plays. I admire a lot of guitar players but I don’t think any I know are as balanced as Eric is. He embodies the whole fierce Freddie King type blues style–or the B.B. King blues style. But he’s also got that flamenco type English guitar thing, which I suppose comes from people like The Kinks and the Stones. He’s just right in between. Joe Walsh, as a guitar player, knocks me out, and Stevie Wonder’s records I like a lot from the point of view of production.

How much have the personal relationships between members of the band changed from the early “hate each other” days? Does any of that feeling still exist?

It exists–the remnants of it exist very slightly. When we’ve all had too much to drink. As you know, a drunken man is a younger man, or thinks he is, and I think we all revert back to childhood a little bit. We were kids, really. The great thing about rock, or the great positive thing about this aspect of rock, is that it does make you feel young.

I’ll be 30 next year and it allows me to go on stage and prance around like a lunatic and feel very young–but it also makes you believe that you’re young and irresponsible, so you end up dong things like smashing hotel rooms and wondering why you’re ending up in jail. Originally the group was run by the iron glove of Roger Daltrey. Roger just isn’t like he was anymore, and hasn’t been for years and years. He used to be very tough and like to get his own way, and if he didn’t he’d shout and scream and stamp and in the end he’d punch you in the mouth. We’d all got big egos in the group and none of us like it and I think about halfway through the first year we all, John, Keith and I, got together and politely asked Roger to leave.

Kit Lambert intervened and said why don’t you give him another chance, and said to Roger, in the future, if you want to make a point, it’s got to be discussed sensibly, no more getting things done by violence. I don’t think he’s ever raised his voice since. I think it shows how much he cared about the group.

Who would you say you’d learned most from actually working in studios?

I suppose it’s got to be Kit Lambert, although I hardly think of him as a record producer. It’s very strange. He and I both learned at the same speed. [He] knew the value of burning studio time. He knew the value of saying, “Right, there’s too many takes, they’re getting worse; everybody over the pub.” Pick everybody up and take them out and perhaps not go back into the studio all night. You’d go home feeling terrible and you’d think “Oh, we’ve had a terrible day and why did Kit take us out?” But the next day you go in and do that track straight away because you’ve built up to it overnight and you get this great recording. He knew about techniques like that, he knew human nature, and he knew about The Who.

The technical part I learned from engineers. I learned from asking questions from our engineer during the Tommy period, Damon Lyon Shaw. I learned from experience from working in my own studio working from tapes. You learn a lot by mucking about with tape recorders and mics and things like that. Making silly home records, which to me was a hobby which was an offshoot from my work.

Also from listening to records–let’s take Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds for example. That is an education in record production. You don’t have to know how the techniques were made, you just listen to it, and Sgt. Pepper. Those are big lessons, both those albums. They take a long time to fully assimilate; in fact I haven’t assimilated Sgt. Pepper yet. I can’t believe it was a four-track album.

When you wrote Tommy, did you write it simply as a Who album or did you always see it going on stage and into a movie?

It was such a long, evolved process. A lot came together in the last few weeks of writing. I had ideas to write a rock opera or an opera-opera–at one time I was studying orchestrations and listening to Wagner and all kind of amazing things, trying to get into full-scale grand opera, and I was going to enlist Arthur Brown, whose voice I thought fell somewhere between a Wagnerian tenor and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and have him as the lead singer.

In the end it all sort of came together. I don’t think it would have happened had it not been for the band’s added energy, and also Kit Lambert’s involvement was very important.

It was great when we did the first Rainbow performance and there I was with the London Symphony Orchestra behind me–it’s a great feeling, affirmation–especially when a few guys from the LSO came up and said really good stuff this, we really enjoyed playing it.

[The Who’s tour has been postponed until 2021. Tickets will be available at here and here.]

Are you happy with the way the [Tommy] movie turned out?

It’s going great, it’s a fantastic learning process. I think the person who’s gained most is Mr. Daltrey, and the funny thing is that my first meeting with Roger was when he was rapping me across the knuckles with the buckle of a belt when I was about 15 or younger–11 or 12–he wasn’t much older. Nowadays to see him on the screen, to see a fully fledged actor, somebody with a really sort of amazingly established voice.

It’s amazing how involvement with somebody in the end–if you stick with somebody–you grow up to love them against whatever odds. If you just stick at it; too many people I think run away from the obvious. Roger could be such an easy bloke to dislike. I’ve disliked him for half the time I’ve been involved with him, and I think maybe for a lot of years he’s disliked or been afraid of me in a funny way. It’s incredible how if you keep at it and keep working together in the end it all becomes unimportant because you know you can count on one another.

Related: Roger Daltrey’s career-spanning 2018 interview with Dennis Elsas

Is there a lot of your material recorded by The Who in the can?

Not particularly. At the moment some of my more pompous ideas I’m keeping in a can marked “solo album,” and the more light-hearted straightforward rock and roll stuff I’m keeping in a can marked “The Who.” But I don’t know how it will all come out.

Often these cans that I mark “solo album” or “private” turn out to be things I just can’t resist getting The Who to do. Quadrophenia, if you like, was my solo album.

We’ve had some crazy ideas which have all nearly worked out. One was that we wanted to ask what we thought were the world’s 12 best songwriters to write us a Who song, and we spoke to Paul Simon, Frank Zappa, Ray Davies and others, and they were all very excited about it, but they all wanted too much time!

Do you think The Who will stay together for the foreseeable future?

I don’t really see how they can do anything else. It’s one of those amazing circles. I think the more we do on our own the more we appreciate working as a group.

It’s hard to explain but it’s a bit like you look up in space and there’s the mother ship, which is The Who proper, and all these little rocket ships that can go out and do very daring explorations, miles and miles away, deep deep into the universe,, places where the mother ship could never go; and they discover new planets and get all kinds of experience but they know that if they got lost someone will come back and save them and pull them back to the mother ship. I think it gives us more freedom, not less, as solo artists, and that’s the funny paradox. I see people leave bands because they don’t get enough freedom, and I think why the hell–they should have more!

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]