When Blood, Sweat & Tears announced, in 1968, that they had a new lead singer, not all of their fans were happy. Although they had only released one album, Child is Father to the Man, it had been groundbreaking, particularly in its incorporation of a jazz-informed horn section. The album had largely been the vision of founder Al Kooper—the keyboardist had written and sung several of the band’s original songs—and now he was out, not by his own choice. His replacement, a Canadian named David Clayton-Thomas, was virtually unknown in the U.S., and you’ll discover how that came about, in this interview. Would they even survive this surprising personnel change?

When Blood, Sweat & Tears announced, in 1968, that they had a new lead singer, not all of their fans were happy. Although they had only released one album, Child is Father to the Man, it had been groundbreaking, particularly in its incorporation of a jazz-informed horn section. The album had largely been the vision of founder Al Kooper—the keyboardist had written and sung several of the band’s original songs—and now he was out, not by his own choice. His replacement, a Canadian named David Clayton-Thomas, was virtually unknown in the U.S., and you’ll discover how that came about, in this interview. Would they even survive this surprising personnel change?

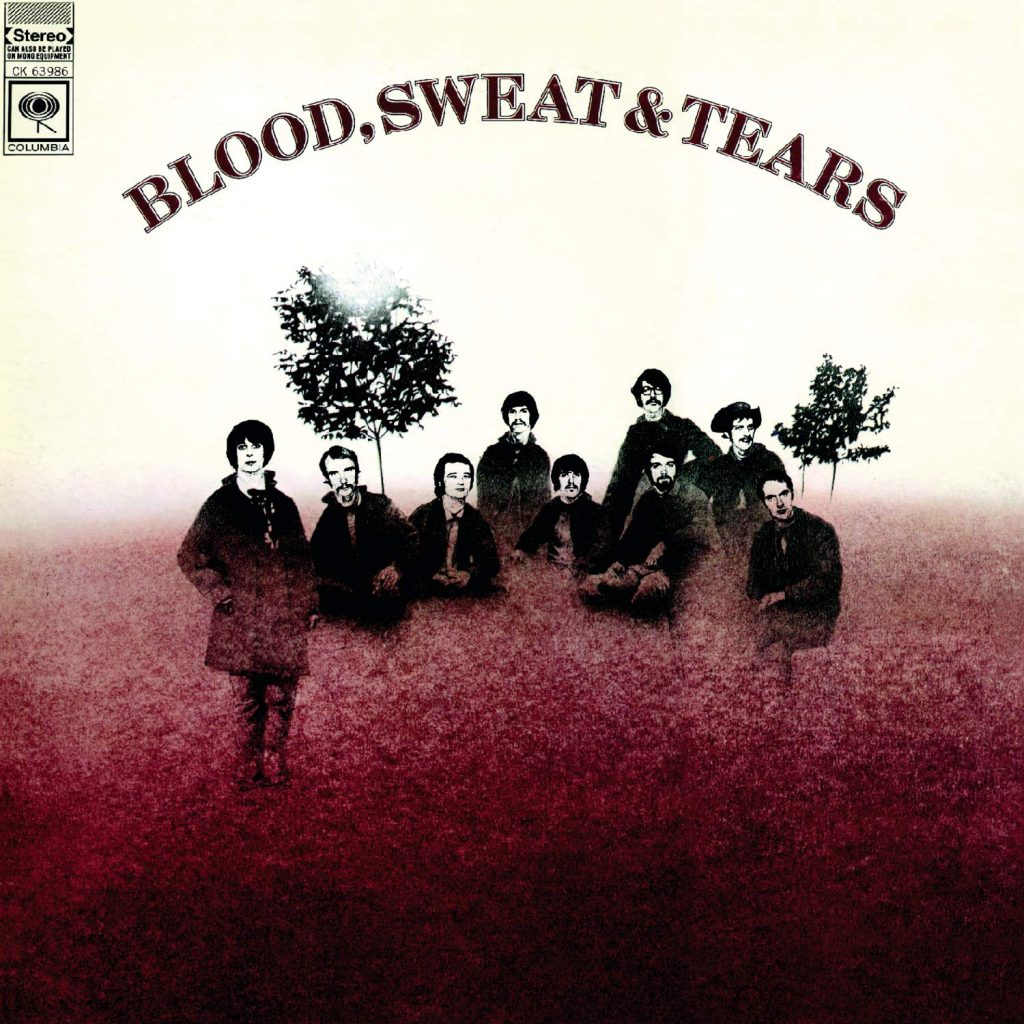

They did—big time. The group’s self-titled second album, which included some of the original members (among them co-founding singer-guitarist Steve Katz, who’d come over to the new outfit with Kooper from the Blues Project in 1967) and a handful of new guys, took more of a mainstream jazz direction in its arrangements, and Clayton-Thomas proved a powerful frontman, his background as a blues singer making him the ideal fit for the band’s new music.

Blood, Sweat & Tears, their second album and first with the new lineup, was recorded mainly in October 1968 and entered the Billboard album chart on Feb. 1, 1969. Within a couple of months it was the #1 album in America. It stayed there for some seven weeks and produced three singles that each peaked at #2: “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy,” an old Motown tune first recorded by Brenda Holloway and co-written by Berry Gordy Jr.; “Spinning Wheel,” by Clayton-Thomas; and “And When I Die,” a Laura Nyro cover. It also featured a terrific remake of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child,” a cover of Traffic’s “Smiling Phases” and more.

Watch Blood, Sweat & Tears perform “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy”

It took nearly two years before the group released its next album, simply titled Blood, Sweat & Tears 3. By that time they had toured relentlessly, including an appearance at the Woodstock festival, but although the album hit #1, the band had already begun losing some of its stature with the rock audience.

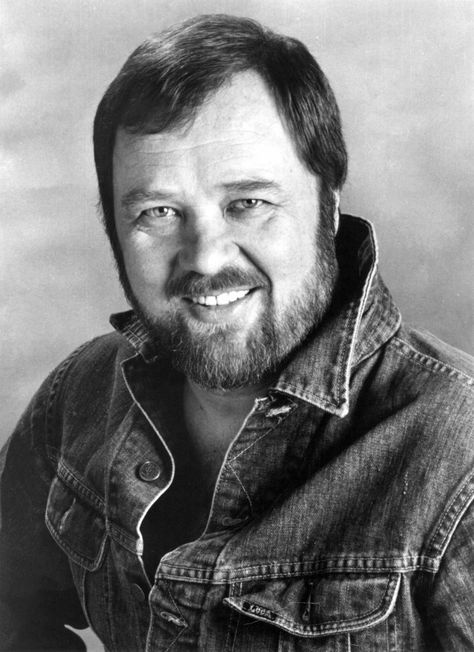

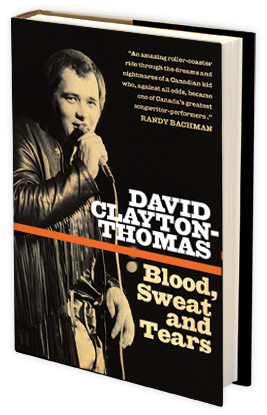

In the first part of our extensive interview with David Clayton-Thomas, the singer recounts how he came to join the band and what it was like to make that smash 1968-69 album. It hadn’t been an easy ride for him: Our conversation begins with his troubled childhood when, still going by his birth name of David Thomsett, the Toronto resident (who was actually born in England on September 13, 1941) spent time locked up for youthful indiscretions. Had he not discovered music while paying his dues, there’s no telling what might have become of him, or with the band—which had already disbanded when he was asked to help resurrect them.

Best Classic Bands: You received your first guitar while you were incarcerated in a reformatory. Would you agree that music literally saved your life?

David Clayton-Thomas: Yes. I was cycled through the system at about 16 years of age and ended up doing four years in a labor camp, and this kid came in and he had a guitar and started to teach me a few chords.

Ronnie Hawkins, whose band The Hawks later became The Band, was sort of a mentor to you.

Very much so. Over the years he’s been a dear friend and still is today. He gave me the first gig where I actually made some money by performing.

You started out singing blues. What attracted you to that genre?

Well, four-and-a-half years in a labor camp, that’s for sure! That’ll make you sing the blues. I just identified with that kind of music, and not just the blues but Woody Guthrie and folk music. Because all I had was an acoustic guitar and that kind of music just came naturally to me. I always loved the Mississippi Delta blues style, Son House and Lonnie Johnson and people like Lead Belly, John Lee Hooker.

Watch David Clayton-Thomas and the Shays perform on Canadian TV in 1965

John Lee Hooker was instrumental in getting you to move to New York, wasn’t he?

Kind of, yeah. In the ’60s, there was no real record industry in Canada. We [his Canadian band, the Shays] had had three number one national hits, and I was still working in the same club. Nothing had changed. John Lee Hooker used to play down the street in a club called the Riverboat and I used to sit in with him. I did it several times over the course of a summer and then one time he said he was going to New York to play the Cafe Au Go Go. I had already been to New York in ’65 or so. We did the Hullabaloo [TV] show, and I absolutely fell in love with the music scene in Greenwich Village. In those years it didn’t live in L.A.; the music industry of the whole world was in eight square blocks of downtown Manhattan. I begged him, actually; he didn’t invite me. I got down to New York and found out that John Lee Hooker had been rebooked; he had gone on an American Blues Festival tour in Europe. So there I was in the club in the afternoon with my guitar and about 40 bucks. I’d just arrived in New York. I didn’t know a single person and the club owner at the Cafe Au Go Go said, “What am I going to do? John Lee Hooker’s canceled. I need a band for tonight.” So I played him a couple songs on the guitar. He said, “Do you have a band?” I said, “Sure,” and went out into Greenwich Village looking for anybody carrying a guitar case or even looking like a musician, and we put together a little band and we opened there that night. We ended up staying there for several months.

The story goes that Judy Collins saw you at a New York club and brought you to the attention of Bobby Colomby, the drummer of Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Yeah, I had a house gig uptown on 46th Street, a place called Steve Paul’s Scene. I was mostly playing guitar but I got to sing a couple of tunes with the band. Judy Collins came in one night and she was a friend of Bobby Colomby’s, and Bobby’s band had just broken up, the original Blood, Sweat & Tears. Al Kooper had left and they had four guys left, but they still had a record contract so she brought Bobby in. I actually already knew Bobby because we played the same clubs. And I knew all the guys in the band; they had all played around the Village.

What did you think of the first BS&T album, Child is Father to the Man?

Great album, very influential. I liked Al Kooper too. I think he’s one of the best producers in the business. He had left and there was a whole lot of contention going on between the band members. Some guys were going to leave and other guys didn’t know if they were going to go with Kooper or stay with the band and it kind of dragged on, and finally my visa ran out and I had to go back to Canada to renew it. I got home and just a couple of days later, Bobby Colomby called me up and said, “Hey, Kooper’s gone. We got four guys left out of the nine. And we still got a record contract with Columbia. Do you want to come down and try out for the band?” I said, “You’re damn right.” I knew [bassist] Jim Fielder real well and I knew they were superb musicians. So I was on the next plane. We had a rehearsal that afternoon, an audition, and it was instant magic. We just knew right off the bat.

Related: 13 bands that changed their lead singers

They were already working on some of the songs that ended up on that second album, true?

There was a couple of songs that were left over, that were actually going to be recorded on the first album. I think the main reason why Kooper left is that the band really were jazz musicians. They had grown up with Mel Torme, Tony Bennett, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, singers—real singers—and they just didn’t feel that Kooper’s vocals were up to the band. There was a big dispute and that’s really what caused the break-up, especially since he was writing a bunch of the songs: “They’re my songs. I’m going to sing them.” The other half of the band wanted to bring in a singer, and that’s what caused the break-up. So some of those songs were left over already and of course they were still performing some of the songs from Child is Father to the Man. So the first thing I had to do was learn some of those songs and in the course of the rehearsals, somebody played me “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” and I loved it. I didn’t even know it was the B-side of a Brenda Holloway single. It was an obscure song and the first time I did it, it just felt right. So we put it back in the show again and it basically brought the house down the first time we played it.

What did [Columbia Records president] Clive Davis think of you joining?

As a matter of fact, the deal wasn’t really settled until we’d had a couple of weeks rehearsal and we went back and opened at the Cafe Au Go Go. I think on the second night Clive Davis came in with a whole bunch of CBS people to see what the heck we’d been up to. That was in the days when record companies actually used to go out to clubs and try to scout new talent; that doesn’t go on anymore now. He was blown away said, “Yeah, let’s get this into the studio right now,” and we were into the studio a couple of days later.

Watch Blood, Sweat & Tears perform Laura Nyro’s “And When I Die”

Did the band members tell you they were looking for a different sound than they had with Al Kooper?

The guys that remained were the ones who were the advocates of not having Kooper sing. So I think many of them were quite relieved that they had a real singer now. I fit right into it because I’d already been working with jazz musicians. I was seeing Oscar Peterson and Lenny Breau and all the greats. I was a huge jazz fan. I’d kind of crossed over from blues into jazz. There’s this very thin line between the two, and my background in jazz and the blues fit perfectly with the band, which, as Clive said at the time, had a rather esoteric appeal. But bringing a blues singer in rooted it, really brought it down to earth, and then people could identify with it.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Child is Father to the Man

You’d already written “Spinning Wheel” before you joined BS&T, right?

Oh, yeah, I wrote it a couple of years before. I had been carrying it around in my guitar case trying to get a record company interested. All the record companies said, “We can’t sell that. It’s jazz. Jazz doesn’t sell.” They were all looking for rock and roll hits. I’d made a little demo cassette up in Canada, and I played it for [BS&T saxophonist] Fred Lipsius and he said, “Oh, I know exactly what to do with that.” And he basically just took the guitar demo and voiced it out for horns and it became our biggest hit ever.

Watch BS&T perform “Spinning Wheel”

How involved were you with the arrangements of the songs on that album?

As a songwriter, of course, you’re very involved in the song because so much of the arrangement is implicit in the song. You can sit down with an acoustic guitar and a tape recorder and make a demo and one of Fred Lipsius’ geniuses was that he would take that and not try to rewrite the song. He would take the guitar lines and voice them for horns, with respect for what the writer wanted. We had two very different writer/arrangers. [Multi-instrumentalist and BS&T founding member] Dick Halligan is completely the opposite. I would give a song to Dick and there would be no consultation whatsoever. He’d take it home and work on it for three or four days, bring it back and the arrangement would be complete. Often it was a complete surprise to me where he went with it, but I didn’t care; he was so good. Freddie and I basically hammered out the details, sometimes painfully. He was very insistent on working with the writer, whereas Dick really didn’t so much. He came up with arrangements like “God Bless the Child,” which is a classic, but as far as my own songs are concerned, like I said, a lot of the arrangement is right there in the demo and a good arranger can only just take it to a better place.

Watch DCT perform “God Bless the Child”

How did [producer] James William Guercio help to shape the music?

Jim came in late. We were already in the studio recording without a producer. We were just kind of jamming and putting it together ourselves. He had done some work with the Buckinghams, I believe, and Columbia thought that we needed a really good tech head in the studio. So he didn’t get involved all that much with the music. His job was getting it down on tape.

That album came out at a time when hard rock bands like Cream, the Who and Hendrix were popular. Why do you think this jazz-influenced music resonated with the rock audience?

I think because in that era something different was good, whereas today something different is the kiss of death. The music industry, particularly in 1968 when we emerged, was dominated by what I call the Marshall [amplifier] bands: three-piece power-rock bands. Here comes a band of Juilliard graduates with horns and flutes and trombones, Basie, Ellington kind of arrangements, a lot of Broadway—Broadway was very influential to Blood, Sweat & Tears. This was the quintessential New York City band; that band, that music, couldn’t have come from anywhere else but off the streets of New York. That was how the players earned their living. A lot of the guys would play a Broadway show matinee, then go up to Harlem and play Latin music or R&B and funk at night, or come down to the Village and play pure jazz the next night. It’s very much like the city itself, such an amalgamation of so many cultures and styles. A sideman musician, to be successful in New York, has got to do it all. It was definitely a school of knowledge for me. It was the first time I ever had to learn to read music. I was just a blues player: give me three chords and I’ve got a song. But to communicate with those guys and get my ideas across, and to hear their ideas and understand where they were going…

BS&T 3 didn’t come out until 1970, two years after the second album. Were you working on it that whole time?

BS&T 3 didn’t come out until 1970, two years after the second album. Were you working on it that whole time?

Not really. I think that was probably a mistake we made in the early days. The [second] record went so big so fast. Most of the guys earned a hundred percent of their living by doing concerts, so, “Let’s go on the road.” And so we basically stayed on the road for almost two years, which explains the big gap between the second and the third album. We did 250, 280 concerts a year all over the world, making a ton of money but not recording. During that two-and-a-half years, before we got back into the studio, everybody had jumped on the horn bandwagon: You had Chicago and Earth, Wind & Fire, who are one of my favorite bands of all time. You had Chase out on the West Coast. Everybody had a horn band. By the time we got back into the studio, finally, to do the third album, Chicago had put out three albums during this time. We weren’t unique anymore. I still think we were one of the best at what we did but we were kind of submerged in a field that we had created.

The second half of our David Clayton-Thomas interview, in which he discusses the Woodstock festival, why he left BS&T and then returned, and what he’s been doing recently.

Watch David Clayton-Thomas and Tom Jones trading blues riffs back in the day

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

7 Comments

I’ve never met David Clayton-Thomas, but I’ve read that a number of people who knew or worked with him couldn’t stand the guy. (Steve Katz’s new book really rakes Clayton-Thomas over the coals.) Apparently he was a major egotist. In any case, he was a hell of a singer and he really made those BS&T hits come alive with that killer voice of his.

Jeff: are you at all related to Stanley, Joe, Charlie? Long Island?

Long Island yes but not related to anyone with those names.

I never thought of the 2nd BS&T incarnation as jazz as much as mor. Pretty bland compared to the earlier Kooper stuff. They made a pile of bux though. Maybe that’s the important thing.

Some of those players, like Lew Soloff and Fred Lipsius, were definitely from the jazz world even if the music leaned toward pop.

The brass section of BS&T did find time to provide horns in 1969 for Three Dog Night hit song “Celebrate” from early 1970.

Another California band from same time frame, Bay Area band Cold Blood, “You Got Me Hummin” (01/24/1970), featured an impressive horn section.

They go on to be famed horns of band Tower Of Power, who provided horns on Santana hit song “Everybody’s Everything” from Oct 1971.

BS&T had a couple of hits released in 1970, from BS&T 3, including “Hi-De-Ho” (08/01/1970), #14 on Billboard 100.

That was the Chicago horn section on “Celebrate.”