“After my brother died,” Gregg Allman wrote in his 2013 memoir My Cross To Bear, “I knew I was going to do exactly what he would have done had it been the other way around, and that was to say, ‘Let’s go play.’” To honor Duane and assure the Allman Brothers Band could continue, “Keeping busy was the only way to avoid going crazy.”

“After my brother died,” Gregg Allman wrote in his 2013 memoir My Cross To Bear, “I knew I was going to do exactly what he would have done had it been the other way around, and that was to say, ‘Let’s go play.’” To honor Duane and assure the Allman Brothers Band could continue, “Keeping busy was the only way to avoid going crazy.”

The 1972 Eat a Peach double-LP, combining live and studio tracks featuring Duane Allman, had become the group’s biggest seller to date, but now it was time to decide if another guitarist should be brought in, or some other solution to the huge gap in the lineup might be possible. Guitarist-singer-songwriter Dickey Betts commenced learning Duane’s slide-guitar parts for live shows, but, talented as he was, there was only so much he could do to replace the irreplaceable.

Enter 20-year-old keyboardist Chuck Leavell, who was playing sessions for Capricorn Records acts after stints touring with, among others, Dr. John and Alex Taylor. At the invitation of producer Johnny Sandlin (who’d been the drummer in proto-Allmans band Hour Glass), Leavell had contributed impressively to sessions for Gregg’s Laid Back solo album. Could it work for a second keyboard to join Gregg Allman’s Hammond B-3 organ? The combination had worked for The Band, Procol Harum and others, and might represent the kind of transformation the ever-evolving Allman Brothers Band could use.

Recording sessions at Capricorn Sound Studios in Macon began in October ’72 with Sandlin overseeing, and eventually stretched to May 1973, due to further unforeseen, tragic circumstances. Bassist Berry Oakley, profoundly despondent over Duane’s Oct. 29, 1971, fatal motorcycle accident, had turned to drink and drugs, and according to roadie Kim Payne (talking to ABB biographer Alan Paul), no longer cared about his future. The whole band was worried about him.

After the band had completed two new tracks, “Wasted Words” and “Ramblin’ Man,” Oakley himself had a crash, hitting a bus with his motorcycle not three blocks from where Duane lost his life. Oakley actually walked away, refusing medical help, but three hours later he was delirious and in great pain; cerebral swelling from a fractured skull killed him after he was checked into a hospital. “Berry had gone out of his way to make me feel comfortable when I came into the band,” said Leavell many years later. “It was a tremendous blow to us all.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Eat a Peach

The search for a new bassist began—Spirit’s Mark Andes and Little Feat’s Kenny Gradney were reportedly on the original “wish list”—with Lamar Williams, an old friend of drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson, getting the gig after an impressive audition. Recording sessions could continue for what became the seven-track classic Brothers And Sisters. As drummer-percussionist Butch Trucks told the ABB website Hittin’ the Note, Betts and Allman would bring in fragments and sketches for songs, a few chords or ideas that would be shaped by the whole band. (This process can be heard on a bonus disc of rehearsals and outtakes with the 2013 deluxe reissue of the album.)

The set starts with Gregg Allman’s peppy “Wasted Words.” Betts’ lyrical slide playing and Leavell’s honky-tonk piano, on a Steinway grand no less, lead the way. “I ain’t no saint and you sure as hell ain’t no savior/Every other Christmas I would practice good behavior/That was then, this is now/Don’t ask me to be Mr. Clean/Baby, I don’t know how,” sings Allman in a tale of considerable vitriol in a jocular vein. As the track concludes, Betts and Leavell “trade fours” in rollicking style.

As a new tune, Betts’ “Ramblin’ Man” actually started to come together during the Eat a Peach sessions. True to his country roots, Betts took off from the sorrowful Hank Williams song of the same name and composed an upbeat, commercial tune that the other band members at first didn’t take to. “We knew it was a good song, but it didn’t sound like us,” Trucks told one interviewer; Leavell says he pushed for the song, telling the others they shouldn’t be afraid of change. Guitarist Les Dudek, who plays electric on “Ramblin’ Man” and acoustic on the instrumental “Jessica,” insists he was supposed to join the band permanently, an assertion vehemently denied by the other musicians, who also bristled at his attempt to get a co-writing credit with Betts on “Jessica.” Dudek subsequently toured with Boz Scaggs and Steve Miller, and had a perfectly fine solo career after that, so there’s no doubting his talent, but his accounts do sometimes clash with those of other participants.

“Ramblin’ Man” became a huge hit single, reaching #2 in Billboard (Cher’s “Half-Breed” and the Rolling Stones’ “Angie” blocked it from the top slot). Dudek told Alan Paul, “We played it all live. I was standing where Duane would have stood with Berry just staring a hole through me and that was very intense and very heavy.” The twin guitars and Leavell’s piano pick out a jaunty intro, and Betts beautifully sings the tale of a man whose gambler father “wound up on the wrong end of a gun.” The concluding jam, with some very swinging drumming and multiple guitars in different sonic flavors, is full of catchy, chiming melodic flourishes.

The gritty “Come and Go Blues” is vintage Gregg. The lyrics carry his characteristic ambivalence about relationships, opening with “People say that you’re no good/But I wouldn’t cut you loose, baby, if I could/Well, I seem to stay down on the ground/Baby, I’m too far gone to turn around.” Listen to how Leavell’s first piano solo is underpinned by Williams’ active, bumping bass part, and how Leavell varies his accompaniment, enthusiastically tinkling away under Gregg’s impassioned vocal for the last verse.

“Jelly Jelly” is Gregg’s re-working of Bobby “Blue” Bland’s 1961 Duke single “Jelly Jelly Jelly” (also known as “Jelly Jelly Blues” when issued by the songwriters Earl Hines and Billy Eckstine in 1941). Near the beginning, after Allman has sung two scorching verses, he and Leavell trade fiery solos. At 4:13 Betts takes over, laying down a multi-part solo that constitutes an homage to B.B. and Albert King. The track demonstrates Leavell’s absolute command of his new spot in the line-up, and how the original ABB repertoire could blossom with new and equal power.

The second side of the original LP begins with “Southbound,” a very fast blues progression with the two drummers and Williams absolutely locked in and Betts doing double duty, switching quickly from rhythm guitar to lead interjections. Leavell’s expert solo at the three-minute mark is followed by a completely unleashed Betts, who gets his Gibson Les Paul in high gear and doesn’t let up.

The joyous “Jessica,” written by Betts in honor of his baby daughter, is one of the greatest of all rock instrumentals. Each section has its wonders, as each player adds his own colors, from Leavell’s Fender Rhodes electric and acoustic pianos, Allman’s organ, Dudek’s acoustic, Jaimoe’s congas and Trucks’ tympani to Betts’ exhilarating overdubbed intertwining guitars.

The finale, “Pony Boy,” begins with Betts’ Dobro, and never strays far from its roots in the Piedmont blues style of Blind Willie McTell and Blind Blake. Betts says he wrote the lyrics about an uncle who, aiming to avoid a DUI charge after a night of drinking, would ride his horse to the tavern or dancehall, because the steed would know how to find his way home with an inebriated equestrian on his back. Williams plays upright bass, Tommy Talton of the Capricorn band Cowboy plays acoustic guitar, and Butch Trucks bangs on a piece of plywood laid on the floor.

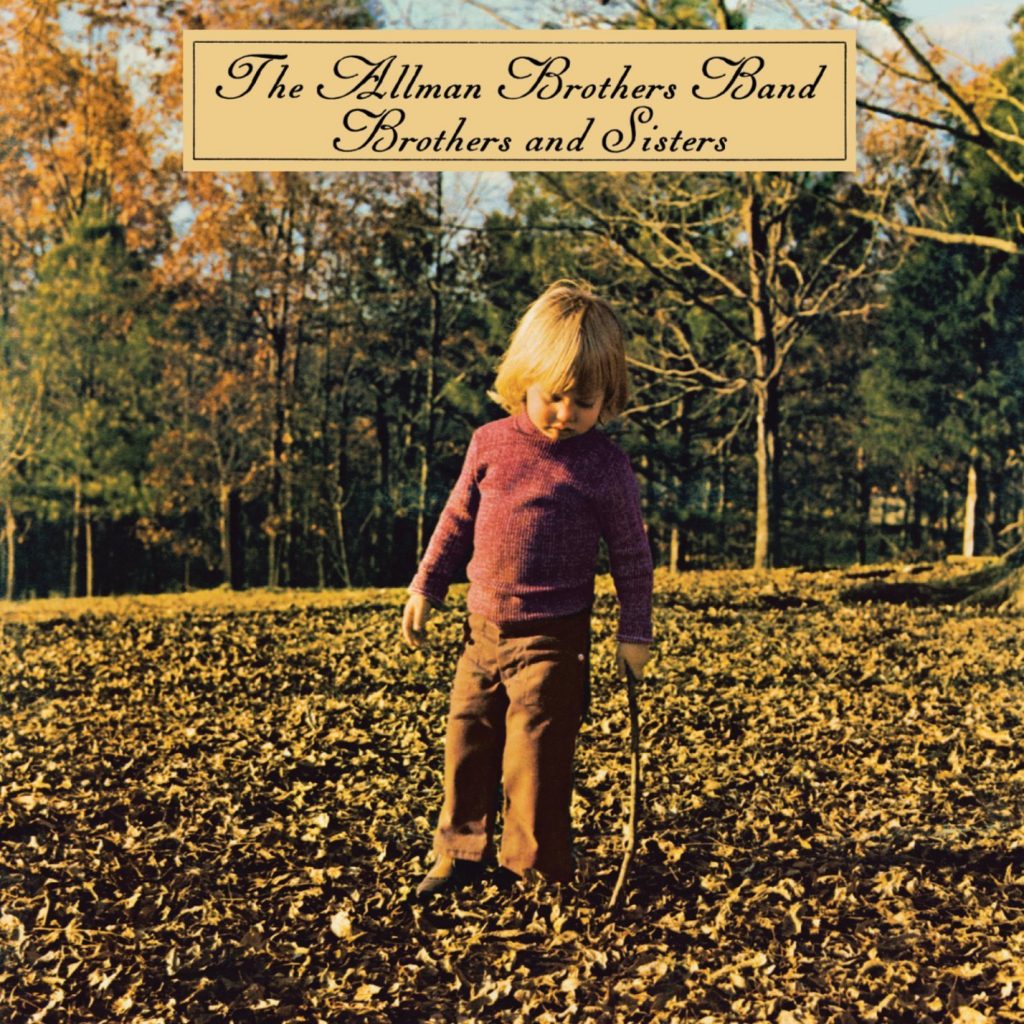

Released only three months after the sessions wrapped, in a cover featuring Butch Trucks’ son on the front and Berry Oakley’s daughter on the back, Brothers and Sisters became the Allman Brothers Band’s fastest seller and first platinum disc. Their concert fees skyrocketed, and they could afford to rent the customized Boeing 720B dubbed “the Starship,” also used by the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. A concert with The Band and Grateful Dead at the New York racetrack Watkins Glen attracted 600,000 fans—more than the count at Woodstock—overwhelming the facility but providing a legendary day of jamming that attendees are still talking about. Even the soundchecks have been bootlegged.

The young Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe joined the 1973 Allmans tour and later used his observations for his film Almost Famous, which is now a Broadway show as well. There are plenty of ’73 Allmans shows circulating, but the Sept. 26 performance from Winterland in San Francisco is a doozy, and can be heard in its entirety in the 2013 four-CD deluxe CD set.

Listen to “Ramblin’ Man” from the Winterland show

Brothers and Sisters, released in mid-August ’73, may not be the best Allmans disc—there’s lots of competition in their catalog for that title—but it remains their commercial peak, a radio favorite, and their only Billboard #1 album, which it accomplished in just its second week on the chart.. When Gregg Allman died May 27, 2017, he was buried in Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery next to his brother Duane and Berry Oakley. Because so many thousands visit the graves each year, a fence was eventually erected to protect them. Still, plenty of people manage to leave mementos and messages about how much the music of the Allman Brothers Band has meant to them. That circle of brothers and sisters keeps growing with each new generation that discovers them.

Listen to “Come and Go Blues” recorded live at the 1973 Watkins Glen festival

Related: A well-researched book takes a deep dive into the Allman Brothers’ Brothers and Sisters era

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

5 Comments

Chuck’s piano manages to give the band a cleaner, more mature sound. The Cow Palace show on New Year’s Eve of 1973 was probably their finest moment as a band, a tasty jazz-infused jam fest. Thanks for the rewind. Nothing like beautiful people writing about beautiful music. Keep it UP.

Unparalleled ABB studio classic LP, to this day.

(Although “Hittin’ The Note” comes extremely darn close.)

While I certainly don’t dislike “Brothers and Sisters,” to me the album represented a shift in the sound and energy of the Allman Brothers Band. Perhaps it was their new reliance on piano in such significant doses on this record, but I felt like the band lost much of the powerful edge it once had, and I’m not sure it ever really got it back. Before Duane and Berry’s deaths, Dickie Betts’ country side was a nice additional flavor the band could easily encompass in a way that seemed natural to them. But post-Duane, Betts’ same country influence became too much of their personality, and the band seemed to lose it’s more blues-oriented sound and approach. The Allmans’ very first LP, produced by Adrian Barber, while having great songs, had a strange kind of muddy fidelity to it. Personally, I loved the way the band sounded on “Idlewild South” where the production and the music seemed to find each other in a way that sounded more naturally like the band live. Then, of course, having such huge hits with “Live At The Filmore” and even a live half of “Eat A Peach” kind of left fans with few reference points to how a studio LP should sound, though the other half of “Eat A Peach” did give us some indication of the direction that the band’s songs and sound on their studio albums would be taking, especially as that studio side featured much of the band finding itself after losing Duane. But, regardless, the characteristic fidelity of what we knew as the Allman Brothers was there on “Eat A Peach,” thanks again to Tom Dowd. All that said, I’ve always thought “Brothers And Sisters” had kind of a flat sound quality with everything right up in your face, much like demos often sound. I never got the feeling of “presence” from that record, even through the good songs that are on it. I suspect the main culprit between studio LPs is that the incredible Tom Dowd produced both “Idlewild South ,” and “Eat A Peach,” while Johnny Sandlin, who was a friend of the band, produced “Bothers And Sisters.” To me, the difference is significant and not a good significance. I suspect Tom Dowd produced the Allmans earlier albums because of Duane’s relationship with him, as he produced “Derek & The Dominoes,” many of Clapton’s solo records, and the best fidelity that Lynyrd Skynyrd ever got on any of their records with “Survivors,” among so many other huge records. There are none better at recording and producing that kind of music than Dowd. Once Duane was gone, the band shifted to Sandlin out of friendship, if I remember correctly, and the Allmans’ records have never sounded as edgy or had more impact, to my ears, ever since.

Well, Tom Dowd DID return to produce more studio albums later on, not only on “Enlightened Rogues” (1979), but also in the 199ies on “Seven Turns” (1990), “Shades of two worlds” (1991) and “Where it all begins” (1994). Still you think they never sounded as good sonically as on the early albums up to “Eat a peach”?

Tom Dowd didn’t make Skynyrd sound good btw. (check out their “Gimme back my bullets” album, which has good songs and performances, but a somewhat disappointing sound), and the first recordings and mixings of “Street survivors” were not used on the actual album… Don’t misunderstand me, I really admire Tom Dowd! But some of your sentences are kind of “off”.. 😉

I do agree that the chemistry and structure of the band changed drastically after Duane was gone. He had been the founder and natural leader, being the only one who was really able to handle Dickey. Afterwards, nobody could replace Duane (even though Dickey kinda took the steer, but with a different approach than Duane had used..), and the band did not function as before. Still great musicians, and plenty of good songs, but not the same “healthy”, positive and cooperative spirit as before Duane’s death.

Just my two cents of course.

That “kind of a flat sound quality with everything right up in your face” was endemic to so many albums produced in the 1970s. It makes a lot of rock music from that era enervating to listen to, especially as compared with the great pop sounds of records from the early to mid Sixties and Fifties.