If any band appeared poised to carry on the mantle of the Beatles at the dawn of the ‘70s, it was Badfinger. Signed to the Beatles’ Apple Records label, the British quartet—Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland and Mike Gibbins–had already scored two Top 10 hits by 1971. The first, an irresistible, bubblegum-y tune titled “Come and Get It,” had been written and produced for the band by Paul McCartney. The second, a punchy burst of pop-rock titled “No Matter What,” was penned by Ham, whose extraordinary songwriting skills were fast becoming evident.

Such was the backdrop for Straight Up, Badfinger’s third LP. Released in the U.S. on December 13, 1971, the album is rightly considered a landmark in power pop. “That’s what the kind of music we made came to be called,” said Molland, speaking about the “power pop” tag with this writer in 2012, for an M: Music & Musicians feature. “We viewed ourselves as continuing in the tradition of the music we grew up with, which was everything up to and including the Beatles. That meant Welsh traditional songs, folk songs, American rock and roll and American vocal bands. We gave the music a hard edge, because we liked rock and roll, but we also made the songs melodic.”

Sessions for Straight Up got underway in January 1971 at Abbey Road Studios, with Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick assisting Ham and Evans with production. Under pressure to work quickly—a two-month spring tour in America loomed—the group completed 12 tracks by March. Powers-that-be at Apple rejected the recordings as “too crude,” however, and George Harrison was brought in to oversee a new round of sessions beginning in late May.

Harrison, an avid Badfinger fan, had already worked extensively with the group, enlisting all four members a year earlier as part of his ensemble on the 1970 opus, All Things Must Pass. “[Of all the Beatles], he was definitely closest to the band,” Molland later told Vintage Rock. Harrison’s overarching plan for Straight Up was to come up with something “more sophisticated.”

“George wanted to smooth things out,” Molland recalled. “He wanted to make more of an Abbey Road-style album. He took our original version of Straight Up, went through the songs and lyrics, and arranged them very much as he did his own music. And then he had us play those arrangements. It turned out great, although to this day I think some of the original versions are closer to what the band was about.”

Related: “Come and Get It,” written by Paul McCartney, was an earlier hit for Badfinger

Molland went on to praise Harrison as an “extremely pleasant” collaborator. “He didn’t act like a ‘rock star’ or a Beatle,” he said. “It was all very comfortable. He had no qualms about strapping on his guitar and playing a bit with us. In fact, I think he enjoyed doing that, as much as he enjoyed everything else. He worked on lyrics with us, and he got excited about the songs as they went down. He started sensing that it could be a hit record.”

Molland went on to praise Harrison as an “extremely pleasant” collaborator. “He didn’t act like a ‘rock star’ or a Beatle,” he said. “It was all very comfortable. He had no qualms about strapping on his guitar and playing a bit with us. In fact, I think he enjoyed doing that, as much as he enjoyed everything else. He worked on lyrics with us, and he got excited about the songs as they went down. He started sensing that it could be a hit record.”

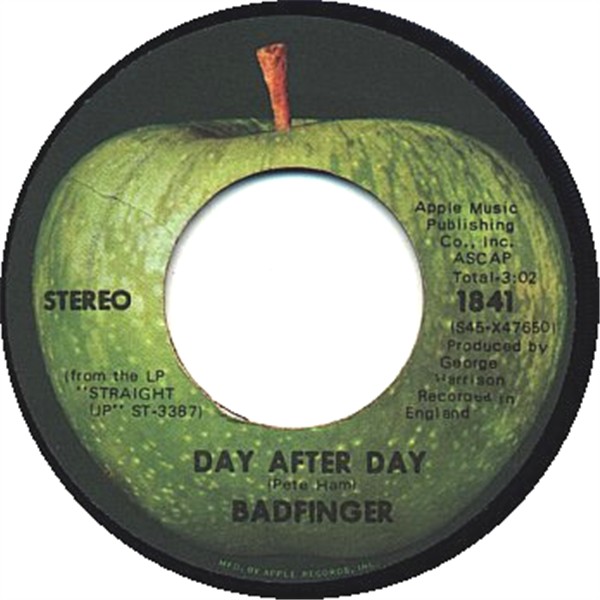

Indeed, the majestic bridge on Straight Up’s signature ballad, “Day After Day,” consists of a slide-guitar duet played by Harrison and Ham. “Pete and I were in the studio, working out the parts, and George came in and asked if we minded if he played on it,” Molland remembers. “Of course we said, ‘No, we don’t mind!’ I gave him my guitar, and he just went to work on it.”

All told, Badfinger completed five songs with Harrison—“I’d Die Babe,” “Sweet Tuesday Morning,” “Suitcase,” “Name of the Game” and “Day After Day.” Other personnel involved in the Harrison sessions included Leon Russell, whose piano work figures prominently in “Day After Day,” and Klaus Voormann, who contributed electric piano to “Suitcase.” Russell added guitar parts to the latter song as well.

Unfortunately, the sessions with Harrison screeched to a halt in late June, when the former Beatle flew to Los Angeles to work with Ravi Shankar. While in L.A., Harrison agreed to stage the Concert for Bangladesh, which effectively ended any chance of his resuming production work on Straight Up. With Harrison’s blessing, Todd Rundgren was brought in to complete the sessions. Despite (or perhaps due to) ongoing tension between Rundgren and the band, the project was completed in just two weeks. High points from the Rundgren sessions included “Take It All,” a Ham-written meditation on Badfinger’s performance at the Harrison charity concert; and “Baby Blue,” a fuzz-riff-driven masterpiece that’s since become a classic-rock staple.

Related: What exactly is power pop?

Molland was pleased with the results, but he was also determined that Badfinger not lose its edge and become a pop lightweight. “We had pop hits, sure, and we were proud of them, but we wanted to be known as a rock band,” he later told Music Radar. “We didn’t want to be one of these twee groups like Marmalade. We placed a lot of value in having great songs, but when it came time to hit the stage, we played two-hour shows and got into jams, the whole thing. If you went to see Badfinger, you got a rock show; it wasn’t just about seeing this group that had some songs on the charts.”

Straight Up, of course, went on to achieve considerable commercial success—including a 32-week run on Billboard’s Top 200 Album chart. The single “Day After Day” peaked at #4 on the Hot 100 chart, and its followup, “Baby Blue,” fared nearly as well. Reviews of the album were generally favorable, and more importantly, the LP’s legacy and far-reaching influence has endured. All of which makes the overarching Badfinger story all the more sorrowful.

Sadly, what should have been a glorious and lengthy future for Badfinger ultimately became a tragedy of Shakespearean dimension. Victimized by unscrupulous management, the group split up just three years after Straight Up was released. Two of the band’s founding members—Pete Ham and Tom Evans—eventually took their own lives. For their many fans, the sorrow lingers, but nothing can diminish the brilliance of what Badfinger accomplished.

“We were forever striving to do something great,” said Molland. “We paid close attention to what our peers were doing, to what the bands of our era were doing, and we wanted to be as good as any of them. All these years later, the music of a lot of those bands hasn’t stood the test of time, but the Badfinger stuff carries on. I think Pete and Tom would be surprised. I know they would be very happy.”

- 10 Great One-Man-Band Albums - 05/15/2024

- The Guess Who’s ‘American Woman’ Album: Distant Roads Are Calling - 05/09/2024

- Joe Vitale: A Chat with the Master Musician - 04/02/2024

9 Comments

Thank you for such a comprehensive view of a band I fleetingly enjoyed way back then (I was 20 when they emerged). I had forgotten how good their music was but reminded how good they were, and still are.

The ‘Baby Blue’ riff didn’t come from a fuzz box; it was distortion. Also, ‘Come and Get It’ most certainly wasn’t “bubblegum.” That said, it’s good to see Badfinger get some ink. Nice article.

For those interested, seek out an excellent book by Dan Matovina titled “Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger”.

Another informative article from BCB; Thank you for the all the effort and research you put into these pages.

Always was a Badfinger fan since the early days, and they nailed it on “Baby Blue”.

My biggest surprise was when I purchased “The Very Best of Badfinger” to consolidate my vinyl on one spin (essentially), was that Peter Ham and Tom Evans of Badfinger had written “Without You”, not Nilsson, which slipped by me (it was the 70’s, after all…)

Great stuff – Thanks for rekindling memories.

Badfinger’s Straight Up is honored quite nicely in the 2019 horror film, Annabelle Comes Home. It was a pleasant and unexpected surprise.

There is only one band member left and that’s Joey Molland always mistaken as a Paul Mccartney look alike.My favorite track from Straight Up?……….”Perfection” but I love the entire album most especially “Suitcase”………ENJOY!!! MF

As cool and accessible as Harrison is reported to have been, it seems like he had trouble staying with things to conclusion. Yes, was famous for his ex-band, but how many commitments could he have? As “Straight Up” was finished by Rundgren, it all ended well, and makes for a good story. But think about how forlorn Badfinger must have been at the time, when Harrison just dropped out and never came back to finish this significant project with them? Harrison did a similar thing while recording his own “All Things Must Pass” leaving the core band at the studio, while he went off for some time to attend to something. Fortunately, that core band put the vacant studio time to good use and began recording their own material, which evolved into the “Layla” LP, and the formation of Derek & the Dominoes. So, once again, Harrison’s drop-out turned into something good. Still and all, one has to wonder what was so pressing that couldn’t wait when George was in the middle of projects with other people. Sure, “The Concert For Bangladesh” was important, and for a needed cause, but when you think about it, to drop the project of one bunch of friends to go off to work with another doesn’t seem that cool at all. As we can see from the “Get Back” documentary, the Beatles’ fame and subsequent isolation appeared to create a bit of arrested development in the maturity of the Boys, as they were used to having everyone cater to them, and doing exactly what they wanted, no matter how it affected other people. George may have been the more “sensitive” Beatle, but it appears his sensitivities were a bit blinded and underdeveloped as well.

Thanks for this insightful piece about a band that deserves greater recognition.

Was there ever a better marriage of music and closing shots than “Baby Blue” and “Breaking Bad”? Amazing….