In Beatles lore there is a single session that stands apart from the others for its workmanlike focus, fecundity and value. This would be the famed 585-minute February 11, 1963, affair at EMI Studios that produced most of the band’s first album, Please Please Me, and all but warmed the English winter itself as the band would soon warm millions of hearts.

In Beatles lore there is a single session that stands apart from the others for its workmanlike focus, fecundity and value. This would be the famed 585-minute February 11, 1963, affair at EMI Studios that produced most of the band’s first album, Please Please Me, and all but warmed the English winter itself as the band would soon warm millions of hearts.

The session climaxed—a verb that knows its way around the room, in this case—with John Lennon’s bravura wailing of “Twist and Shout” while stripped to the waist with the lights turned down. The Beatles had gotten themselves into an Indra Club-like mood to accompany their inarguable groove.

When a spent Lennon emits that final “whoo,” one has the feeling that these four young men knew that something impressive had been accomplished on this day—not, necessarily, that they had just made a record that would own the charts and send them on a way that no one else had ever gone. Rather, good, hard work had been done, and that was enough, because it was very good work indeed.

But the February date wasn’t the only extended single-session wonder of the Beatles’ 1963 campaign. Tucked away in the middle of the year is one of the finest sessions in all of rock and roll history. Viewed as a self-contained document, which the imaginative listener is encouraged to treat as an LP, the same as one does with Please Please Me or Sgt. Pepper, it represents the straightest, purest shot of what this band was most about. Call it the great aggregator of Beatles music in taste, range, attitude and dexterity, with a bug’s eye view of a sensibility that made both this band possible, as well as such moments, extended or otherwise.

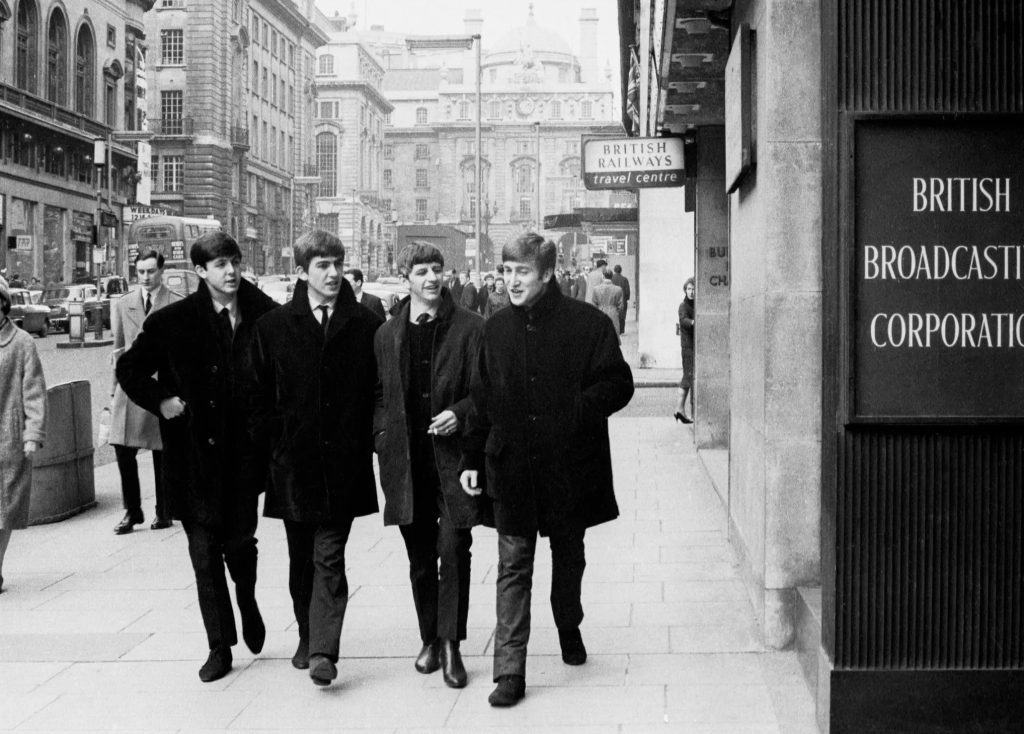

It’s July 16. The Beatles’ schedule is enough to make a whirlwind worry that it’s being lazy. The band has its own new radio program on the BBC called Pop Go the Beatles, its theme song a bluesy riff—complete with John Lennon harmonica vamp—on the “Pop Goes the Weasel” childhood ditty (foreshadowing the “yellow matter custard” line of “I Am the Walrus”).

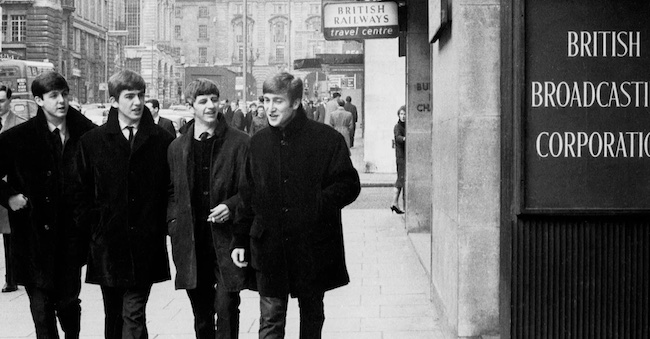

Arriving at the BBC’s London studio, the plan was to tape and stockpile three full shows that would end up going out over the air on the Light Programme the 6th 13th and 20th of August.

On this very same day, the program cut on July 2 was broadcast, a remarkable affair in its own regard, featuring covers of Arthur Alexander’s “Soldier of Love (Lay Down Your Arms),” Elvis’ “That’s All Right” and Chuck Berry’s “Carol,” alongside the band’s own “There’s a Place.” The Beatles were fashioning fresh achievements in their artistry as recently made examples of their art entered the world, like they were lapping themselves, but in a winning way.

The group ended up taping 18 songs—while bantering with each other and host Rodney Burke, of whom they were clearly fond—in under eight hours, producing the session that best shows what the Beatles loved, musically-speaking, and why the Beatles’ own music was so easy to love.

People talk about Ringo Starr’s playing on “Rain” as proof that the man really could drum—when this is a band that wouldn’t have been nearly what it was with anyone else in the drummer’s chair—but his playing on the July 16 cover of Elvis’ “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Cry (Over You)” is showpiece stuff. Not that it’s showy. But if you wanted to enter Starr—with his enfilading fills—in a drum contest with the likes of Keith Moon, Ginger Baker and Ian Paice, here would be a cut worth putting forward and you’d take your chances.

It’s the first song we get, and we know immediately that the Beatles are bang-on and smoking hot. They’re not just here to fulfill obligations. This was a day all about showing off their considerable stuff and delighting in inarguable legitimacy. These Beatles were into being these Beatles, one might say, on July 16, 1963, fully aware of their evolution as a band since Starr’s arrival the August before and their developed capabilities. Sometimes you play for other people. Sometimes you play for yourself. And sometimes you play for both.

Related: Taking a fresh listen to the Beatles’ Decca audition tapes

The period from summer 1963 through to the end of that year is the foremost for in-concert Beatles music. We hear it here, at the Swedish shows in October, and the Christmastime Liverpool homecoming gig. The sound quality for the BBC airshots could vary, but this was the best the fidelity ever got. Were one to make a list of albums that didn’t exist but should have, then this mega-session could have slotted between Please Please Me and With the Beatles, and the official canon would have been that much richer.

The period from summer 1963 through to the end of that year is the foremost for in-concert Beatles music. We hear it here, at the Swedish shows in October, and the Christmastime Liverpool homecoming gig. The sound quality for the BBC airshots could vary, but this was the best the fidelity ever got. Were one to make a list of albums that didn’t exist but should have, then this mega-session could have slotted between Please Please Me and With the Beatles, and the official canon would have been that much richer.

The range stuns because there is no drop-off in quality, regardless of material or type of material. Paul McCartney sings “The Honeymoon Song”—a number from a 1959 Michael Powell film based on the ballet El Amor Brujo–with axiomatic conviction, helped along in a light-footed way by George Harrison’s colorful fills. His guitar tone throughout this day alternately chimes and stings, and the brightness of his playing on “The Honeymoon Song” presages the dipped-in-gold plucked notes of the “Nowhere Man” solo two-and-half years later.

You have the impression that Lennon—who generally tolerated rather than welcomed such McCartney forays—would have honestly dug this interpretation. Simultaneously, it’s as if the Beatles are so locked in in this moment, that they’re also leaving breadcrumbs for their future selves, being that aware of the scope of their talents. Today is never just about today, but also tomorrow, and so forth.

You have the impression that Lennon—who generally tolerated rather than welcomed such McCartney forays—would have honestly dug this interpretation. Simultaneously, it’s as if the Beatles are so locked in in this moment, that they’re also leaving breadcrumbs for their future selves, being that aware of the scope of their talents. Today is never just about today, but also tomorrow, and so forth.

McCartney’s singing deploys that same scrubbed and well-washed tone marking the start of “Hey Jude.” One is hooked instantly by that vocal purity of expression. No one else in rock history has had it to a comparable degree.

Then again, arguably no one has topped John Lennon as a singer of rock and roll in various forms of the medium, including as a soulful balladeer, like with the cover of the Teddy Bears’ “To Know Her is to Love Her,” a number that’s not hard for a lesser singer and band to turn into treacle.

This is the classic Lennon voice in its prime. When a fan of the band writes in to the BBC asking for a song from “leather lung Lennon,” they meant this John Lennon, the quintessential rock and roll singer in the vocal embodiment of the rock and roll sound. There are times when one thinks that all Lennon had to do was open his mouth and allow anything to come out and it would be rock straight from the spigot of the music’s ideological pump. Lennon could make Larry Williams’ “Bad Boy” sound urgent, important, vital, when it really isn’t, or at least not anywhere else or on its own.

But this version of “To Know Her” is shot through with a similar strain of eulogistic devotion as Lennon’s portions of “A Day in the Life.” A listener wonders if he had his mother Julia in mind in delivering this performance, as the song’s author, Phil Spector, was thinking about his father. A committed Lennon was an unbeatable vocalist. The overall effect of the song borders on the hymnic, but as though that liturgical offering had been sourced from a missal itself dipped in the waters of rhythm and blues.

The Beatles fostered community in the works that we might say most made them them, and the backing vocals of McCartney and Harrison suggest friends turning up at the house of another friend to give him whatever he needs to get through what he’s experiencing. This is the sound of both the process and that outcome. And it’s also one of their choicest covers, which is saying something, given that the Beatles, for all of their vaunted originals, were rock and roll’s cover kings.

The Beatles fostered community in the works that we might say most made them them, and the backing vocals of McCartney and Harrison suggest friends turning up at the house of another friend to give him whatever he needs to get through what he’s experiencing. This is the sound of both the process and that outcome. And it’s also one of their choicest covers, which is saying something, given that the Beatles, for all of their vaunted originals, were rock and roll’s cover kings.

The day proved a star-turn for everyone, both individually and in how each musician contributed to the power of the collective. Harrison sang Carl Perkins’ “Glad All Over” and Buddy Holly’s “Crying, Waiting, Hoping”—plus a tease of the Donays’ “Devil in Her Heart,” a number that will feature on the second album—and acquits himself with style, but what’s most notable from the George side of the ledger is that we get Harrison in guitar domination mode.

He gives the songs throughout the session a lot of juice. Holly and Perkins were big-time influences, but Harrison’s individuality as a player was among his foremost strengths. At the Beeb, he obviously felt free to cut loose in ways he might not have on record. After all, these were not “official” recordings. So, have fun, was a portion of the mantra, and the sound of the Beatles having fun making music is an awfully artful—and joyous—sound.

McCartney super-charges Little Richard’s “Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” like he’s been galvanized by the gauntlet his mates have thrown down and wants to dash it himself, as does Lennon with “Twist and Shout.” The quality of the latter number could vary widely, depending on how much Lennon wished to throw himself into it. A taxing song to sing. He gives it the old art school try here, and later—on the last episode of Pop Go the Beatles—the group would cut a version that’s bested only by the famous album-closer, a kind of warm-hearted—and larynx-shredded—send-off to a program the Beatles obviously loved doing.

This performance of “Twist and Shout” is from a few weeks later.

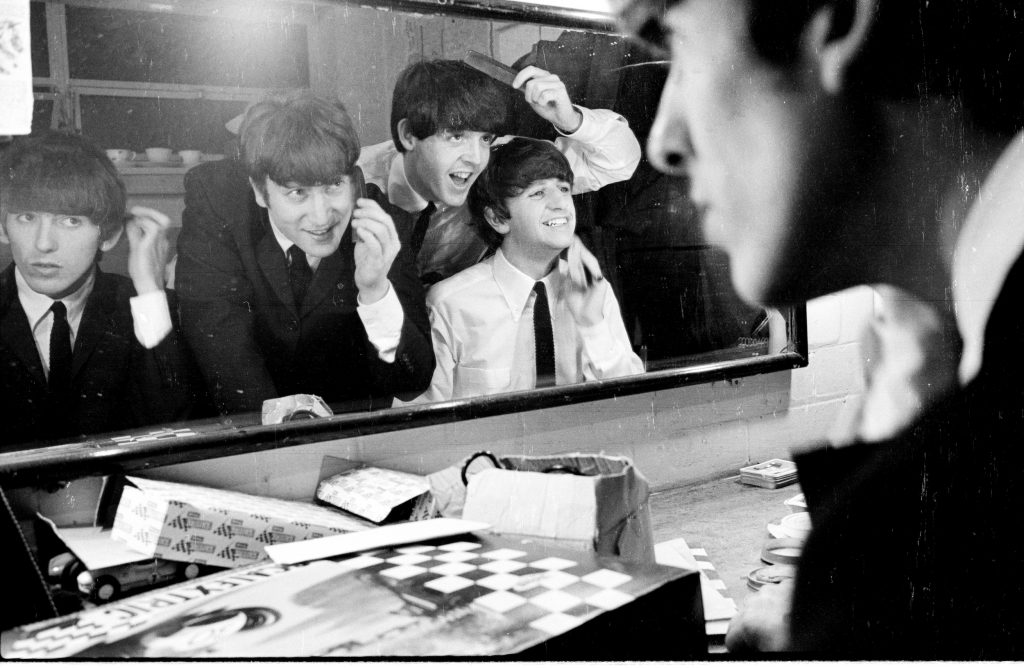

They joke with each other, and it’s like we’re in their private locker room where the boys are being the boys, but witty, close-knit boys, with their own language nestled within the hold of the English language, these Beatlesesque beats and verbal riffs. We don’t want to leave, and we might even feel homesick when we do.

The Beatles tackle Ray Charles’ “I Got a Woman” as this countryish, rhythm and blues-infused side shuffle. There’s a touch of “Get Back” in the proceedings, with all of the movement being horizontally rather than vertically oriented. It’s a motley mix, as if the Beatles both understood and amplified what Charles was doing with his penchant to blend. He lay into the country aspect, whereas the Beatles—retaining the rhythm and blues groove—would substitute country with folk and call it Rubber Soul. That’s a ways off, but Beatles music like that was also happening before it did, as these session kings show us repeatedly at the BBC.

As if the feast wasn’t sumptuous enough, the Beatles decided to include a rendition of a little number they had recorded a little more than two weeks prior at EMI. It happened to be “She Loves You,” one of the towering achievements of popular art.

There are no “down” performances of “She Loves You,” but this first blast of musical heaven on the BBC is as up as it gets. They knew they had something special, and if anything, the Beatles sound more excited than their listeners may have been. After all, they had had a fortnight to come to grips with their own newness, whereas those tuning in at home in England would have been knocked sideways.

That’s how it goes with the entirety of this session. The Beatles never sounded more like the Beatles, though of course they never sounded like anyone else. But sometimes in life we’re just a little more ourselves in a given place and time, and in what we’re up to. Hear these Beatles being as deep as they ever got in the being of Beatles, and you’ll treasure this session as much as you treasure them.

Related: The Beatles’ December 1963 concert in Liverpool

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

2 Comments

What a superb treat to read, remember, and listen to some of the very greatest Rock n Roll of all time. Thank you!!

A friend of mine gave me the German vinyl double album. It’s one of my faves and I don’t even own a player!

In my car’s CD player the Beatles at the Beeb is on all the time. This “stuff” was what I loved those guys for -ever!