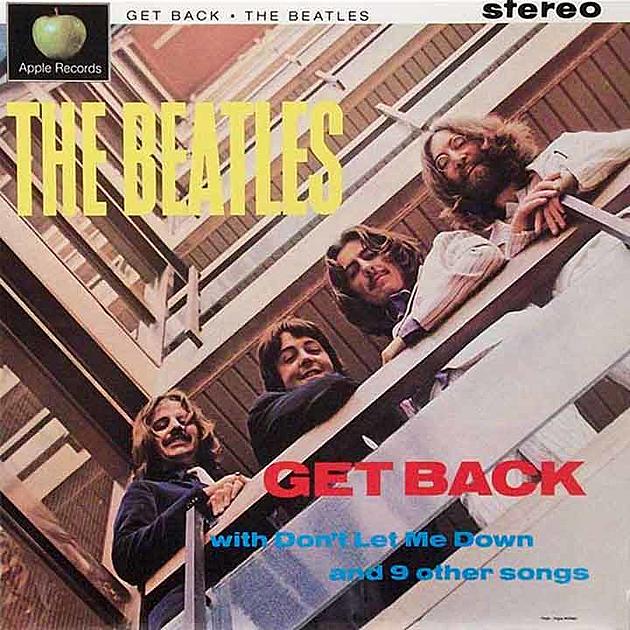

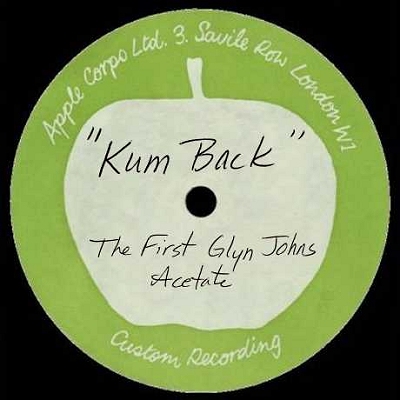

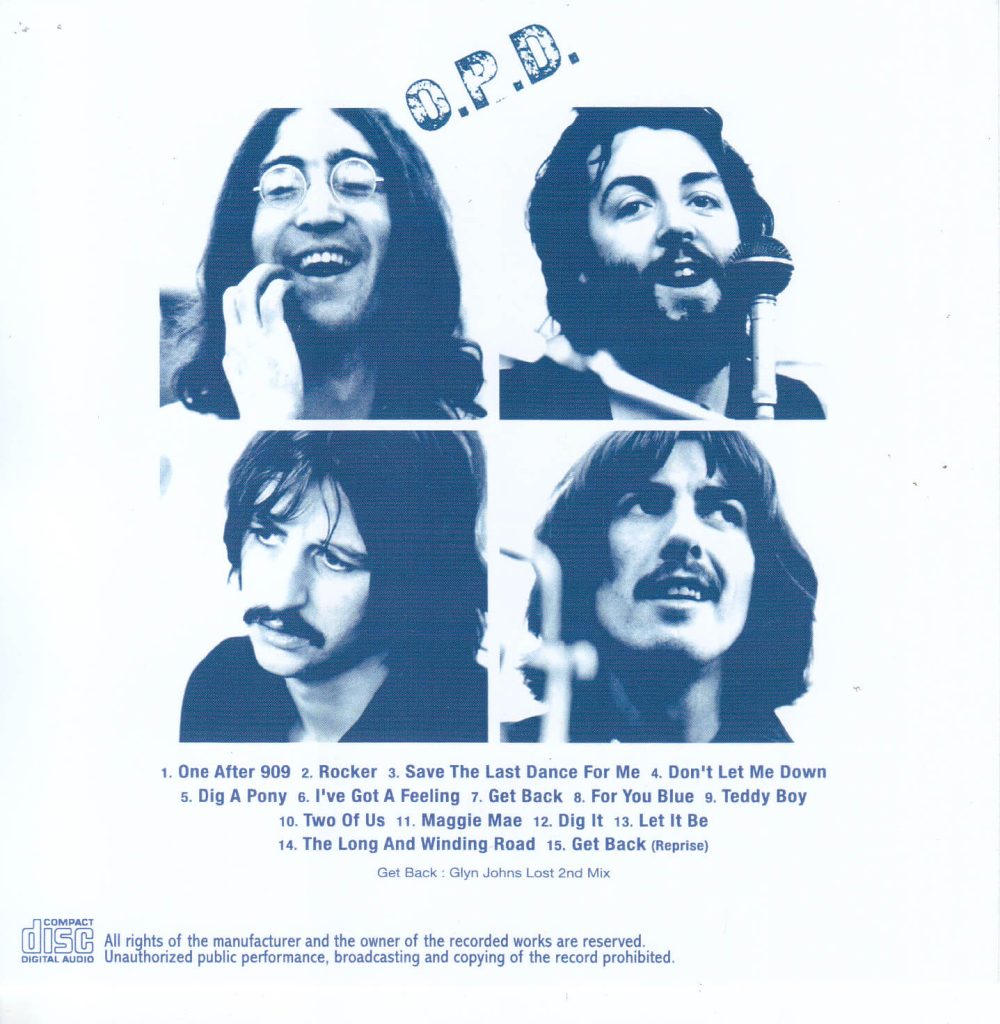

Before the Beatles made their final album, they made the album that would be the final album they released. And before either of those were released, a different version of the eventual-last-to-be-released LP…circulated. And was broadcast (sort of).

The end of the Beatles’ career became a bit tricky, but in order of discussion we’re talking Abbey Road, Let It Be and Get Back. Abbey Road came out September 26, 1969. Let It Be hit shelves May 8, 1970. And somehow, before both of them, there was supposed to be Get Back in summer 1969, which would have meant no Let It Be in the start of the new year and Abbey Road, the last album, would have been the last album released. Got it?

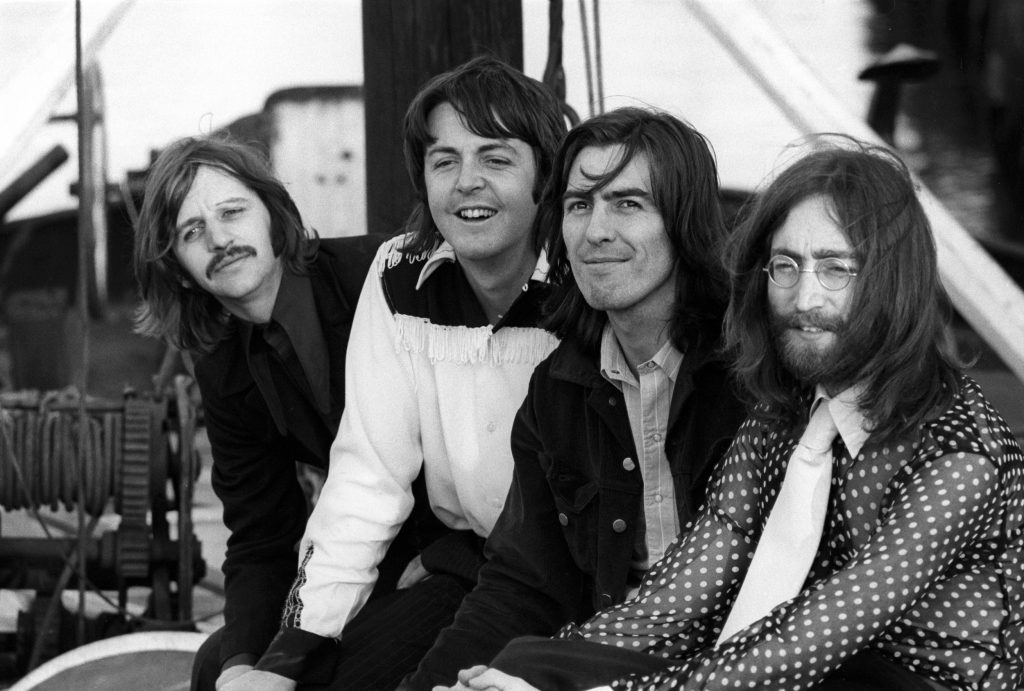

Confusion abounded for The Beatles over the course of their final year. Such is life when lives start to go in different directions, but with business—plus relationships and, in this case, art-making—still to tend to.

The album that would have been the Beatles’ penultimate LP was fashioned from the January 1969 sessions that were intended to bring the band back to their roots. The thinking was that in doing so, fires would be rekindled, and those fires would light the roads of new directions.

The Beatles, though, had become a bit like that friend you know you’re not going to know much longer. What do you tend to do over those last gatherings? You stoke the coals of the past, which is one way we say goodbye to people whom we still care about. The relationship is complete, but it deserves to go out on as warming a note as possible.

Get Back was free of the strings that would later be imposed by producer Phil Spector, brought in at the eleventh hour to either perk up Let It Be with much-needed life, or deliver the mortal blow to put the Beatles out of their misery, depending on where you stand with that issue.

Get Back was free of the strings that would later be imposed by producer Phil Spector, brought in at the eleventh hour to either perk up Let It Be with much-needed life, or deliver the mortal blow to put the Beatles out of their misery, depending on where you stand with that issue.

The Beatles never sounded so ramshackle as they do on Get Back, which is officially preserved now on the expanded Let It Be box. Even with the songs of the sprawling White Album, born in the wilds of India, the Beatles hadn’t transitioned to music-making over songwriting. The compositions still (mostly) came first. They were professionals aware that their writing would be in front of the public for evaluation, but with Get Back, we have a band not far removed from a campfire singalong, albeit the studio—or rooftop—version. It’s the Beatles’ variant on what the Beach Boys had done with Beach Boys’ Party! four years earlier.

In a sense, it must have been liberating, representing one of the few instances in which the Beatles weren’t thinking in terms of the record-buying public but rather solely themselves, with the Magical Mystery Tour film and “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)” being other examples. Get Back wouldn’t do—unless you were the Fugs, Captain Beefheart or Frank Zappa—as your first statement as a band, but it could be what you released later when your name alone generated interest and there was an automatic curiosity factor. An album like that might be attempted every now and again, though not every time, or else you’d lose your common-man audience, but the Beatles weren’t going to be around much longer anyway, so down came the hair.

In a sense, it must have been liberating, representing one of the few instances in which the Beatles weren’t thinking in terms of the record-buying public but rather solely themselves, with the Magical Mystery Tour film and “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)” being other examples. Get Back wouldn’t do—unless you were the Fugs, Captain Beefheart or Frank Zappa—as your first statement as a band, but it could be what you released later when your name alone generated interest and there was an automatic curiosity factor. An album like that might be attempted every now and again, though not every time, or else you’d lose your common-man audience, but the Beatles weren’t going to be around much longer anyway, so down came the hair.

The posited Get Back LP is the 1969 version of a Beatles 1963 BBC radio session half a dozen years later. There are assorted covers—Fats Domino’s “I’m Ready,” the Drifters’ “Save the Last Dance for Me,” the Liverpool street shanty, “Maggie Mae”—interspersed with worthy originals (“Don’t Let Me Down,” “I’ve Got a Feeling”) and two numbers in “Get Back” and “Let It Be” which were to this stage of the Beatles’ career as “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had been to an earlier one. Bookending compositions.

But it’s the vibe that makes Get Back an album that’s almost rustically avant-garde. If the Beatles were ever to toss aside shoes and clothes and make music in field and forest, it’d be this album that would have changed our perception of their final campaign together.

As with those BBC sessions, there are snippets of songs between the proper songs—such that the notions of the two blur—and plenty of good-natured piss-taking.

Related: When Paul McCartney welcomed Ringo Starr and Ronnie Wood to sit in on “Get Back”

The BBC was a clubhouse of sorts, and the Beatles let us listen in, but they pulled up the ladder all the same. We get the sense that even all of this time after, they couldn’t help but share a joy when they were together, and that joy took a form not dissimilar to their banter with each other in the presence of Brian Matthew or Rodney Burke, or when John Lennon’s friends passed around one of his issues of The Daily Howl an ostensible lifetime ago during the days of school exams and po-faced headmasters.

The Beatles of Get Back were crunchily rustic in spirit if not thusly situated in actual geography. Had you been told they had ventured off beyond the heath for a boys retreat, carrying guitars and a tape recorder with them and this was what they produced on their sojourn, you’d accept that.

The Beatles of Get Back were crunchily rustic in spirit if not thusly situated in actual geography. Had you been told they had ventured off beyond the heath for a boys retreat, carrying guitars and a tape recorder with them and this was what they produced on their sojourn, you’d accept that.

The jams are loose but bracing. Four-and-a-half minutes of “Dig It” may seem like three more than anyone needs, but Lennon was into it and we end up being, too. Maybe this was what it was like on those first trips to Hamburg and it was necessary to kill time with extended grooves that didn’t require dexterity and were instead all about power of personality, feel, balls and ad-libs.

The Beatles did enthusiasm very well, and you rarely think they had to work that hard to manufacture any—it was just what came out when they played together. Paul McCartney’s “Teddy Boy” is the exception, and hearing it on this perspective LP you can understand why his three bandmates disliked it as they did.

The tune isn’t so much the issue as how the thing goes nowhere; and when it ought to stop—or, rather, each time it ought to mercifully stop—it takes another circuitous trip around itself. Plus, it doesn’t have much to do with a teddy boy, but rather some mother-son dynamic (with a kid named Ted). We don’t need the latter—we have “Let It Be” for the mothers.

“I’ve Got a Feeling” is one of those better-than-you-think Beatles songs that isn’t discussed often enough, perhaps because it’s cobbled together, like “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” albeit with less—and less discursive—parts. “A Day in the Life” aside, the Beatles songs that garner the most prestige present a single, unified front. They move A to B, with no wacky digressions or insertions, elegant examples of songwriting in its purest form.

The amalgamated approach almost comes off as cheating, compositing rather than writing, when we have this subconscious supposition that artists like the Beatles should always be writing instead, because they wrote better than anyone else.

“I’ve Got a Feeling” does indeed suggest ad hoc songwriting, a jam having become a number, a cut. Led Zeppelin worked this way, not the Beatles. It’s an invigorating piece all the same, a Beatles-based song of the self and their most Walt Whitman-esque/Leaves of Grass moment.

“I’ve Got a Feeling” does indeed suggest ad hoc songwriting, a jam having become a number, a cut. Led Zeppelin worked this way, not the Beatles. It’s an invigorating piece all the same, a Beatles-based song of the self and their most Walt Whitman-esque/Leaves of Grass moment.

And despite the subject matter of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” which in one section involved nuns and phalluses, that language was oblique, so it was still something of a shock—even in 1969 at the high point of the hippie era—to hear these former moptops going on about wet dreams and how everyone was having them communally as part of a blissful, unified movement in which pleasure, and emissions, continued post-consciousness.

Listen to the Anthology 3 version of “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”

Some of the music found its way to the outside world at the time—as so much rock music was wont to do in 1969, the year of the great bootleg flood—and got played on a radio station like WBCN in Boston that September (days before Abbey Road was released), with the DJ predicting a cease-and-desist letter from Apple. What went out over the air was this Get Back/Abbey Road mishmash. You couldn’t fault the enthusiasm, which came from a similar place of healthy hedonism as the Get Back record itself. The LP we’re free to listen to at our convenience now was mangy, and so were cutting-edge radio stations. Lennon in particular probably would have dug the spirit.

“Let It Be” is the centerpiece of that eponymous album, but on Get Back it’s “Two of Us” that’s the lynchpin. If you want to picture young Lennon and McCartney on the side of a road, guitars in hand, waiting for a car to come along to bum a ride while on holiday, this is the song, in the best setting, to do that to.

This “Two of Us”—which is different in the middle section of Get Back than at the start of Let It Be—takes us back, but without forfeiting that “road out ahead.” You never want to underestimate the value and opportunity provided by the latter, as the Beatles knew and had understood since their start.

Those two words, Get Back, have been so many things for the Beatles—a song, a plan, an attempt to revive enthusiasm, a docu-series—but when you listen to the LP version as a cohesive experience, what we have feels a lot like a genuine concept album. Further, an organic concept album that couldn’t help but be itself, and required no planning; the being—these guys being what they were and were to each other—taking care of everything.

Very few albums make it feel like they’re taking care of everything, the people who made them, and us, the listeners. In its thatched-roofed, lived-in way, Get Back represents an ideal, or an ideal come to life, or was life all along. Whether that’s behind or ahead doesn’t really seem to matter. That it’s out there does.

Listen to “Get Back” from the Beatles’ Anthology 3

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024