Being the rock and roll badass that he was, John Lennon doubtlessly felt comfortable urging on Paul McCartney to “really knock the shit” out of “Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey,” a Little Richard cover graced with a gusty Macca vocal that was captured in a solitary take. Lennon’s version of the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout,” which famously caps off the band’s debut album, Please Please Me, was likewise a single-attempt affair. Its standing in the Beatles’ history—occupying so crucial a spot as it does in closing one pop epoch and opening another—means it’s much better known than McCartney’s Midwestern romp, which was tucked away on Beatles for Sale, the first Beatles record that anyone thought was in any way a downer, though it’s aged just about as well as anything they did.

Being the rock and roll badass that he was, John Lennon doubtlessly felt comfortable urging on Paul McCartney to “really knock the shit” out of “Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey,” a Little Richard cover graced with a gusty Macca vocal that was captured in a solitary take. Lennon’s version of the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout,” which famously caps off the band’s debut album, Please Please Me, was likewise a single-attempt affair. Its standing in the Beatles’ history—occupying so crucial a spot as it does in closing one pop epoch and opening another—means it’s much better known than McCartney’s Midwestern romp, which was tucked away on Beatles for Sale, the first Beatles record that anyone thought was in any way a downer, though it’s aged just about as well as anything they did.

Listen to their studio version of “Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey”

The same can be said for a song that itself is about being down, and which has never engendered much chatter. That would be McCartney’s original composition “I’m Down,” a portentous number for the band—and McCartney in particular—that also acts as a palliative to assorted false impressions. The man became an octogenarian on June 18, 2022, so how about we give one of his most underrated efforts a reconsideration? Works pretty well for the birthday soundtrack as well.

One of the oldest Beatles saws is that Lennon sang the bangers, McCartney the ballads, as if each had a dominant musical theme to which they doggedly hewed. Part of that has to do with the end-all-be-all vocal ballsiness of the “Twist and Shout” cover, and also that Lennon returned in essentially the same role to close out the band’s second album, With the Beatles, with a version of Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want).”

One of the oldest Beatles saws is that Lennon sang the bangers, McCartney the ballads, as if each had a dominant musical theme to which they doggedly hewed. Part of that has to do with the end-all-be-all vocal ballsiness of the “Twist and Shout” cover, and also that Lennon returned in essentially the same role to close out the band’s second album, With the Beatles, with a version of Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want).”

One is in a place and a time, and one might become known for a quality that another shares in equal measure, by dint of being put forward in certain high-profile situations. Call it the vicissitudes of being in a band, even the biggest band ever.

But if Lennon treated himself to the more flamboyant vocal turns early on, McCartney was always creeping in the weeds, ready to explode into full view. Another Little Richard cover, “Long Tall Sally,” highlights the EP of the same name, released in summer 1964 as a stop-gap between the world-changing A Hard Day’s Night LP and the perpetually autumnal Beatles for Sale. Rock and roll does not have a better EP, but that’s the nature of EPs—they’re for the hardcore people, especially after their time, in the real-time of their actual release, has come and gone.

McCartney channeled Little Richard with the added perk that he put his own spin on what had been Richard’s brand of singularity. I can’t think of a rock and roll singer harder to emulate than Richard. To hear his early singles in particular is to experience a form of vocal modernism as shocking in its way as anything dreamed up by James Joyce or Igor Stravinsky. McCartney was not to be deterred. Lennon by and large took the Chuck Berry and Arthur Alexander numbers, covers-wise, and George Harrison and Ringo Starr were the country and western men in the band, but I bet they all got a huge charge out of McCartney doing Little Richard, and you can tell that the latter loved that he was able to do so, with his own distinct flourishes. It’s not like Paul McCartney was just going to copy anyone.

Richard shrieked more than McCartney did, with that falsetto voice that sounded like it was never going to come down from its own private ether. McCartney operates with just a hint of gravity, the notion that his voice remains tied to the earth. He’s a control guy, a singer who can cut loose better than anyone, while remaining in charge. Back in his prime, McCartney had total command as a singer, and enviable range that dwarfed Lennon’s. Lennon knew it, but what are you going to do? I think that’s one reason why Lennon the singer emoted like he did, as part of the competitive aspect between the band’s copestone talents.

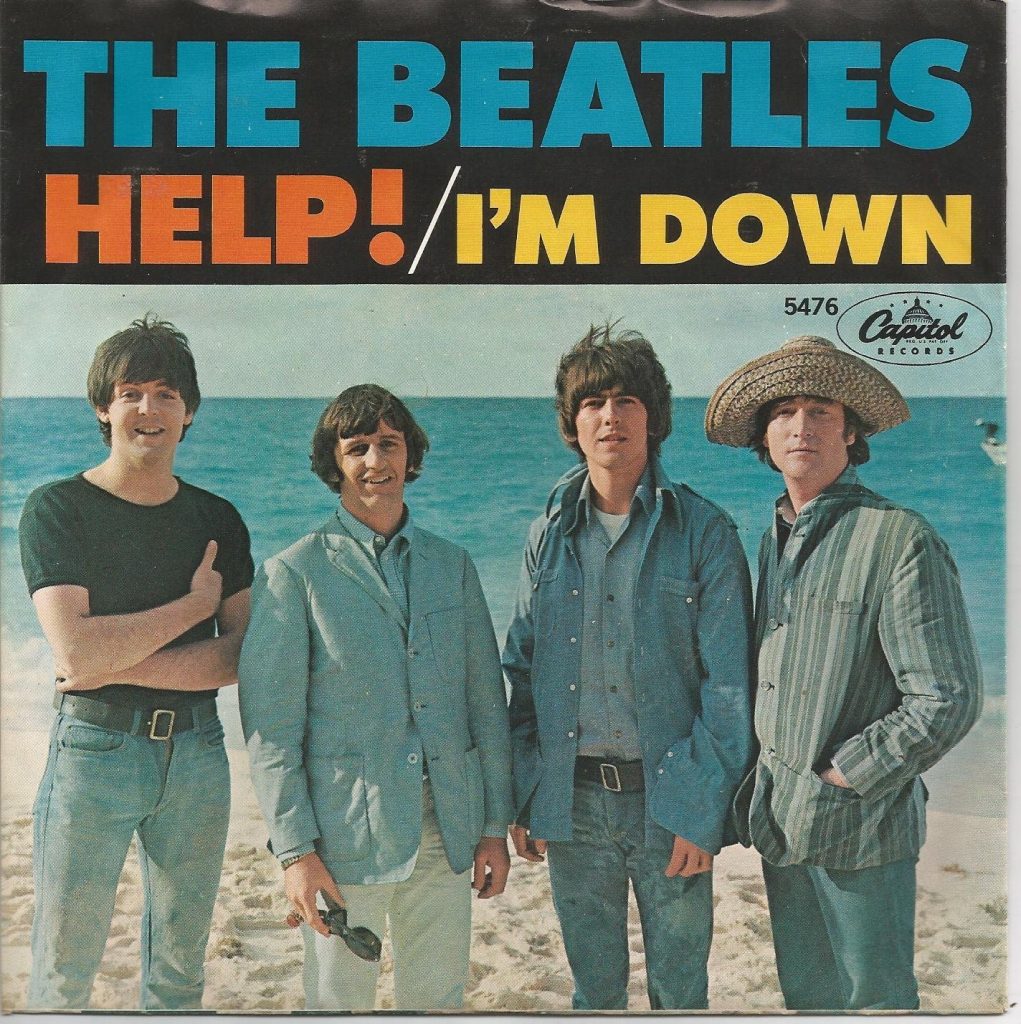

But then we get to 1965, and the Beatles, if you know where to look, were getting heavy. Lennon boasted that his “Ticket to Ride” was the first heavy metal number. A lot of that has to do with the lugubrious pacing—we’re not that far from the realm of Black Sabbath, but Sabbath couldn’t pen a tune like this. Lennon’s “Help!” thrashed like nothing had in popular music until its release. Harrison’s guitar seemed to channel the same super-charged electricity that Dr. Frankenstein put to work in the 1931 Boris Karloff picture. Lennon didn’t scream the song, but you can hear just how raw he makes his voice. Then we come to “I’m Down,” the Beatles’ stealth raver, on the B-side of the Lennon confessional. The song’s visibility—or lack thereof—is freighted with a certain irony.

The Beatles used the number to close their Shea Stadium gig in August 1965, still the most famous show anyone has ever played in this country, with one primary act. Lennon commanded the organ, and was so amused by McCartney’s hell-for-leather vocal that he went full-on loon and played the thing with his elbows.

Watch that Shea Stadium performance of “I’m Down” by scrolling to 27:42 in the video (or just watch the entire set!)

If you weren’t around at the time, you easily could have been unaware of “I’m Down” until the release of a double compilation called Rock ’n’ Roll Music in 1976. The song was left off the 1973 set, 1962-1966—otherwise known as the Red Album—which legions of Beatles fan grew up with, and still do, I bet. A teeth-cutter. Those in the know were miffed at the time, blaming Apple Records manager Allen Klein for the perceived cock-up. It featured later on the first of the Past Masters sets, a catch-all mostly of singles, along with the Long Tall Sally EP and a stray version of “Across the Universe.” Still, despite its closing pride of place at Shea at the apex of Beatlemania, you could have missed the “I’m Down” entirely.

The song is a joke-blues, delivered at then-radical volume. You might postulate it as “Helter Skelter” before “Helter Skelter.” The White Album song was McCartney’s riposte to the Who. He cited it as the Beatles’ “I Can See for Miles,” which doesn’t make a lot of sense, given that “Miles” is sinister, clear-eyed and leaping/peripatetic, and “Skelter” is quasi-menacing—tongue-in-cheek style—boggy and plodding. Whatever—the amps were turned to 11.

“I’m Down” has a lighter, jocular quality because McCartney’s vocal exuberance tells us that the singer isn’t really that down. He’ll get over his girl laughing at him—if he hasn’t already—and we have the impression that he’s on this oft-mentioned ground rolling around with mirth, or simply the delight of good rock and roll, well-delivered. You know those guys who play guitar and are like, “Now it’s time to get on my knees and rock out”? That’s how McCartney sings “I’m Down,” only with that virtuoso voice of his. Lennon gets in on the joke as well, providing the cod-basso profundo response the same as he did, intriguingly, on the band’s cover of the Coasters’ “Three Cool Cats” at the inglorious Decca audition—with Pete Best on drums—on January 1, 1962. From small acorns grow large Beatles.

Watch the Beatles perform “I’m Down” on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1965

For all of their compositional prowess, their studio mastery, their comfort with experimentation, their zest and acumen for innovation, the Beatles were an energy band. The best bands are. The best artists are energy artists. You experience energy in Walt Whitman’s verse, a Jimi Hendrix guitar solo, a Bach fugue, a Pollock drip painting. Energy doesn’t mean volume, it doesn’t mean a fast pace, in and of themselves. It means a prevailing animation—undeniable evidence of the life force. The Beatles stay with us because of that life force, more than anything else. That energy is what kicks both “She Loves You” and “A Day in the Life” up into the pantheon’s pantheon. The Beatles-sphere. “I’m Down” is the garage rocker done by pros. The Beatles liked to say, “We can do this, we can do that, we can invent this other thing, what else do you want to see?” They liked to compete. They wanted other bands to know that they were better. They always wanted to get ahead, and leave the competition behind. Michael Jordan was an assassin as a basketball player. The Beatles were that way as a band.

Related: What were the #1 singles of 1965?

Energy begets energy in Beatles art. Thus we have George Harrison playing a guitar solo that you’ll be forgiven for doubting he had in him. I love George Harrison as a guitarist, but if I’m being honest, a lot of that has to do with him playing the lead guitar parts on songs by the Beatles. He has his moments—no one has ever talked about his one and only acoustic guitar solo with the group, on “And I Love Her,” which will always strike me as stunning. But he shreds on “I’m Down.” Often times either Lennon or McCartney summoned a Harrison solo with a scream. It was his cue. “Okay, George, do your thing.” There were instances, though, when Harrison needed no summoning. Check out his fretboard rave-up on the Hollywood Bowl version of “Long Tall Sally,” for example. There’s a cheat that some guitarists have used to brilliant ends: start your solo a touch early. Regarding guitar solos for the ages, the MC5’s Back in the USA album is a veritable cornucopia. Most of them start about a half bar too early. That revs up the excitement. Which is exactly what Harrison does on “I’m Down.” He cuts loose, then McCartney comes back to cut loose vocally. We all know that lame cliché, “Dance like no one’s watching!” “I’m Down” is akin to playing like no one will ever listen. Get naked and shake your rump.

McCartney’s following vocalizations are wild. All over the tonal map. There is always method to what prime McCartney did, though, the sense that whatever was undertaken would also lead to a very viable elsewhere. Three years later, McCartney had another song-based reason to declaim the manna of release. “I’m Down” is a song of liberation. Sometimes, owning where you’re at is its own form of freedom, even if where you’re at—joking or no—is less than ideal, or downright awful. “Hey Jude” was another McCartney freedom song—the freeing of the self; or the friend, if you go with Lennon’s interpretation of the number.

Watch another live take of “I’m Down,” this one from Germany

“Hey Jude”’s long coda is not the same without the razzle-dazzle vocalizations—also all over the tonal map—that come straight from the B-side that most people have never paid attention to. We’re going from down to up, via a pathway between post-Little Richard hell-raiser and anthemic paean to human connection that most songwriters would give a solid slice of their soul to have written. That idea—born of the energy of promise and the promise of energy—always reminds me of an outtake of “I’m Down,” when McCartney adopts a mock American accent, before the boys blast off.

“Let’s hope this one turns out pretty darn good, huh?” he chides.

I’d say yeah.

Listen to that outtake here…

Bonus Video: McCartney continued to perform “I’m Down” in his solo years

***

Colin Fleming is the author of a recently published entry in the 33 1/3 series on Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963. This piece on “I’m Down” is excerpted from his newly completed book, Just Like Them: A Piece by Piece Guide to Becoming the Ultimate Thinking Person’s Beatles Fan. Find him on the web at colinfleminglit.com, where he maintains a voluminous blog, and on Twitter @colinfleminglit.com.

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

2 Comments

I met Little Richard in LA when I was the keyboard roadie on the “Wings over America” tour. He told me about when he first met The Beatles when they supported him at The Star Club in Hamburg and how he admired them and that Paul was a big fan of his and that he likes to think that he helped The Beatles on the road to stardom. I think Paul agrees with that.

One of my Beatles favorites. I play it more than occasionally on my weekend oldies show, though I play the 1996 anthology version, bookended by Paul’s comments.