There are certain gigs—and the surviving tapes of these gigs—that qualify as what I would call a core collection of Beatles live recordings. They’re notable not just for whatever in-concert highpoints they represent for the Beatles themselves, but as straight-up vital documents of rock and roll.

There are certain gigs—and the surviving tapes of these gigs—that qualify as what I would call a core collection of Beatles live recordings. They’re notable not just for whatever in-concert highpoints they represent for the Beatles themselves, but as straight-up vital documents of rock and roll.

You want as many highpoints as possible to stand in line like competing mountain peaks. The musicality of the performance is one. How much the band was into the gig and that it meant something to them is another. The instrumental finesse. The vocal prowess. A historical aspect doesn’t hurt. Sound quality can be a further boost. Stakes are nice.

As a blended overlay of the above sweet spots, the recording of The Beatles at the Empire Theatre in Liverpool on December 7, 1963, feels like a Christmas present that gives all the year long. The Beatles were between things—namely, domination of the United Kingdom, and global domination, the latter of which would ramp up significantly in two months, when the Beatles traveled to New York for the first time.

The timeline was tightly packed from December 1962—when the band played its last residency in Hamburg—to this point here at the close of 1963. Two albums had come out as well as the “From Me to You,” “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” singles, with the band’s last date at Liverpool’s Cavern Club having occurred on August 2.

Consider for a moment: in the summer of 1963 you could have seen the Beatles in a small underground club, and then a few months later they’d be cordoned off from the public by whatever means possible.

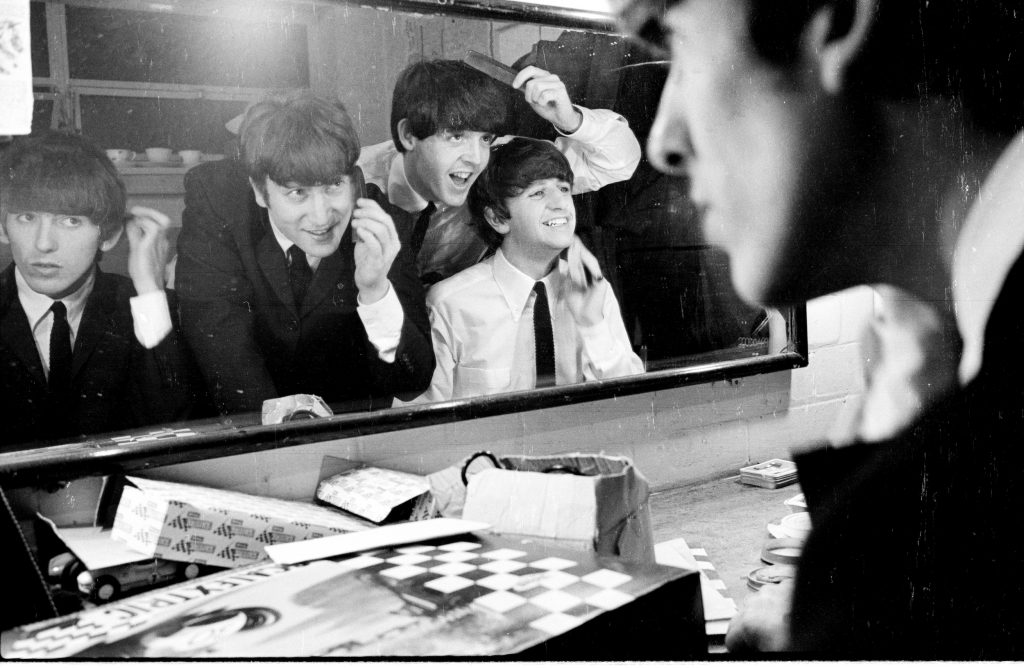

Liverpool’s Empire Theatre was where the members of the band—before the group existed and all relevant parties knew each other—attended shows as kids, soaking up as much in-person rock and roll ambiance as possible.

This wasn’t just home, but a venue for foundational memories, and now, with the arrival of the Christmas season of the greatest year of their life—to date—the Beatles were on that same stage.

This wasn’t just home, but a venue for foundational memories, and now, with the arrival of the Christmas season of the greatest year of their life—to date—the Beatles were on that same stage.

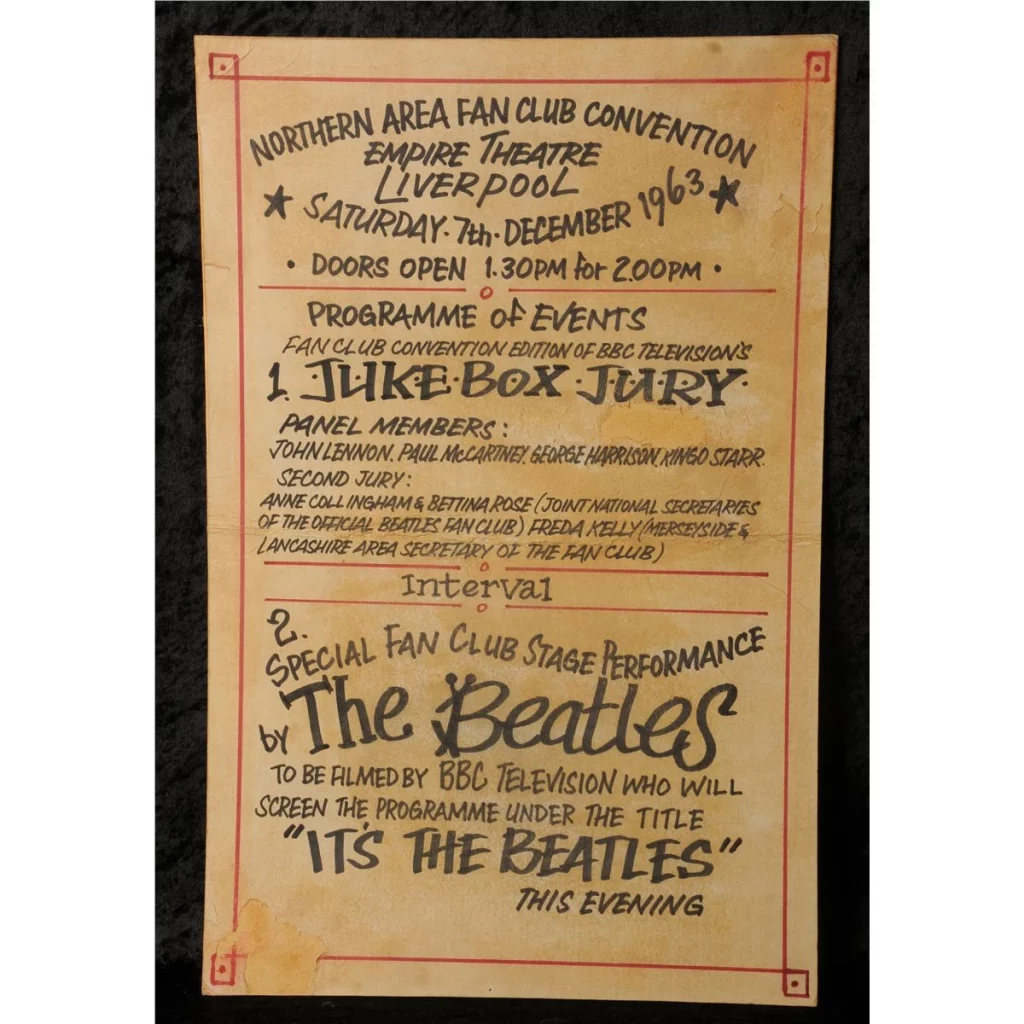

Next time you’re poised to tell someone how short of time you are, reflect on the Beatles’ itinerary for this afternoon and evening: first, they were to tape an episode of Jukebox Jury here at the Empire, then play the matinee gig in front of 2,500 fans, before taking themselves to the nearby Odeon for two more shows that evening.

But it’s that mid-day show that stands apart as a tender triumph, and also a bittersweet one; the Beatles didn’t know what was coming next, but they understood that they were deep in the process of having outgrown their hometown, if they hadn’t already.

The Beatles were invested in this gig, and they perform with a precision—and a playfulness—that is unique for them in this sort of environment. You get something of what was already the old spontaneity, but with the polish that marked the likes of The Ed Sullivan Show appearances.

The official history claims that Ringo Starr played but one drum solo during his tenure with the band—at least during the fame years—with said solo coming on Abbey Road, but this bountiful gig from the Beatles begins with Starr performing by himself for a lively 17 seconds.

At which point, the full band hurls itself into as energetic a performance of “From Me to You” as one will find. The falsetto vocals go higher than usual—perhaps higher than at any other time.

There’s great glee and gusto in this rendition. It’s the sound of a group caring about where they’re at, for whom they’re playing, what all of this represents; they want to make this show count for as much as possible.

The number concludes, but the Beatles don’t pause at all, but rather sustain the opening explosion into “I Saw Her Standing There.” This is a gig for the George Harrison buffs; his solos are piping hot with no flubbed notes. Ringo Starr starts dropping bombs at the end of Harrison’s guitar break here on “I Saw Her Standing There,” and you know the boys are well up for it.

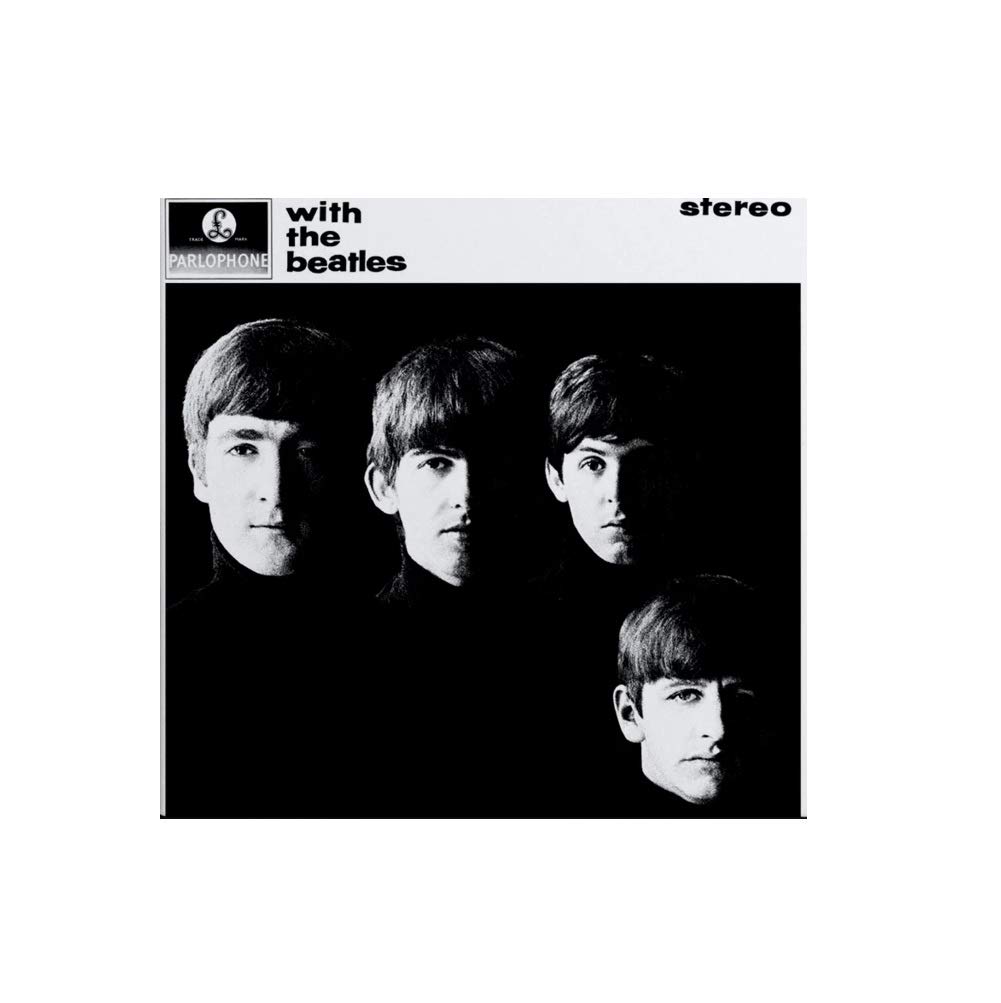

With the Beatles had just come out, and the execution of the following rendition of “All My Loving” shows how proud the Beatles were to display the new wares. The Paul McCartney and George Harrison harmony passage has a tonal flavoring distinctive from the various other iterations, of which there’s a decent number. The rhythm guitar post doesn’t lend itself to virtuosity, and Beatles rhythm guitarist John Lennon was no virtuoso, but he comes off like one with the deft, rolling triplets he dishes out here. Everyone is doing their thing at the best of their abilities.

With the Beatles had just come out, and the execution of the following rendition of “All My Loving” shows how proud the Beatles were to display the new wares. The Paul McCartney and George Harrison harmony passage has a tonal flavoring distinctive from the various other iterations, of which there’s a decent number. The rhythm guitar post doesn’t lend itself to virtuosity, and Beatles rhythm guitarist John Lennon was no virtuoso, but he comes off like one with the deft, rolling triplets he dishes out here. Everyone is doing their thing at the best of their abilities.

Listen to the complete audio from the December 7, 1963, Liverpool show

Harrison introduces “Roll Over Beethoven” as a number they’ve been trotting out “for about 28 years.” The mind boggles in trying to gauge how many actual times they’d played the Chuck Berry song in their homes, at rehearsals, in Germany, in so many moments that no one else in the world was privy to.

Harrison tears it up on the guitar. Rarely do you hear him this aggressive and hard-edged. His voice, too, has a noticeable rasp, and he sings the hell out of the song. “Boys” is next, with an introduction by Lennon, who jokes that they were going to have Starr sing his new song from With the Beatles—which, of course, was “I Wanna Be Your Man”—but he hadn’t bothered to learn it yet. The Lennon wit.

Starr’s vocal is drowned out, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing, and the latter statement is no knock on Starr, but rather a tip-off to what we get to hear and focus on instead, because the entire band is pumping away on this song.

Instrumentally, this isn’t how we think of the Beatles. McCartney’s bass playing on the chorus is as inventive as what we later experience with Sgt. Pepper numbers like “With a Little Help from My Friends” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” but with the raw brutality of the bass style he sometimes favored on the White Album. As you listen to these musicians play together on “Boys,” you wonder if it’s the Beatles we’re hearing or the Sonics.

More Lennon japing precedes a McCartney jaunt through “Till There Was You.” Throughout the show, the Beatles have spoken to this crowd like they know most of the members of it. They reference the Cavern. It’s very chummy, like a going-away party, with a special send-off.

Related: The Beatles at the BBC, July 1963

From there it’s right into a version of “She Loves You” that is as inspirited as the studio original. Is there any song in rock and roll history that releases the endorphins like “She Loves You”? The entire show is an energy jolt, but one that’s beautifully paced, so that the jolt is also sustained for the full half hour. You could go so far as to say that the Beatles excelled at redefining what a jolt could be.

On the bridge section of “This Boy,” Lennon channels his most primal voice—the one that we heard on the studio version of “Twist and Shout” and which would surface later on “Don’t Let Me Down” and at the start of his solo career. It’s such a naked, vulnerable moment in which we can tell how dear it was to Lennon, of all people—with the toughness he cultivated in the place where he grew up—to emote as fully as he could.

There’s considerably more vocal exertion and volume to come after McCartney thanks everyone for coming to “this little get-together.” The word choice resonates; clearly it wasn’t accidental. McCartney knew the deal; this was like having friends over for a boozy party, minus the booze, and in a theater instead of a parlor. Same feel, though.

Which brings us to “Money” (That’s What I Want)” and “Twist and Shout,” performed back-to-back, with this cocksure—but friendly and uplifting—“take that, Liverpool!” feeling in the air.

Each of the Beatles had grown up with the idea of performing your particular party piece at those little get-togethers, and a four-man version of that was happening now.

Lennon’s voice all but duets with Starr’s drums at points of “Money,” this brilliant Tamla soul-type groove c/o these rhythm makers of this port city. “Twist and Shout,” meanwhile, is one of those no-quarter sorts of performances, what is intended as a definitive capper that no one and nothing could follow.

Still, there’s a coda to bring matters full circle, which seems especially appropriate on this occasion: an instrumental version of “From Me to You.” But even there the Beatles’ zest for these people and this place and what it’s all meant to them, is evident. Harrison and Lennon trade guitar licks, before the former launches into “The Third Man Theme.” It registers as unscripted and wild—and, above all, joyous.

Still, there’s a coda to bring matters full circle, which seems especially appropriate on this occasion: an instrumental version of “From Me to You.” But even there the Beatles’ zest for these people and this place and what it’s all meant to them, is evident. Harrison and Lennon trade guitar licks, before the former launches into “The Third Man Theme.” It registers as unscripted and wild—and, above all, joyous.

There were the two shows to follow that night, and the Beatles would be back at the Empire right before Christmas for a dry run—minus the skits they’d be performing—of their upcoming London Christmas shows. But that gig featured a mess of other artists on the bill. It wasn’t nearly as one-to-one.

The December 7 matinee is a box-checker, with admirable sound quality to boot, to make a Lennon-esque pun about it. It makes for a warming, heartening experience of a tape, with some of the sharpest, most precise playing of the Beatles’ performance career.

The concert was filmed, but the Beatles had major reservations about the results, with the camera often managing to be in one place when it should have been somewhere else. Fine—let this just be a record in both the musical and historical senses.

For to hear that recording is to have a deeper appreciation of where they had come from, and, in turn, to where they wished to be going. Which is to say, as far as their talent could take them. Goodbye Liverpool, and hello all things beyond.

Watch all of the available footage from the December 7, 1963, Liverpool show

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

1 Comment

Great article. Very informative. Love the deep background stuff from the so-called early days on the Fabs in the pre-Sullivan UK.