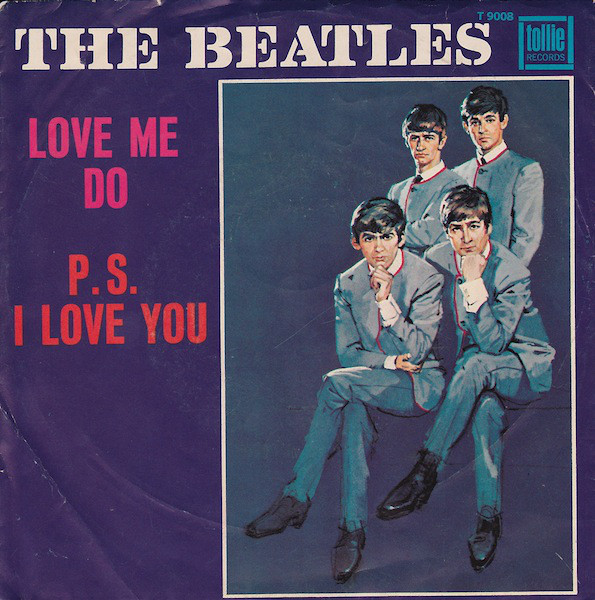

“Love Me Do,” the Beatles’ first single, has never received the plaudits that so much of their output has, and yet, there may have been no more important statement of purpose for the band.

Released in the U.K. in October 1962, “Love Me Do” was also the Beatles’ first hit, reaching #17 in the charts in Britain—even if that was largely because manager Brian Epstein bought up many copies himself, a technique known as “padding.” [Incredibly, it would be another 18 months before the song was released in the U.S.]

The Beatles themselves regretted that they were missing out on the excitement back home—the presumed afterglow of landing a hit—by having to go to Hamburg for a final time as a club band. “Love Me Do” was where the action was, and who could fault The Beatles for wishing to be near their first trace of an epicenter?

The first noticeably different thing about “Love Me Do” is its unusual title. Love me do? The language mirrors a crisp, highly class-conscious, English form of conversation, the province of an older woman in society rather than a working-class Beatle.

“Please pour me some more tea, do,” is the construction. The Beatles merely omit the comma. Do is not a play on “too”—it’s a polite directive.

There was a lot of Mitch Murray in the air for the Beatles during the period of mid-1962, until they nailed the peppier version of “Please Please Me,” an improvement with readily apparent hit potential, over the slower, Roy Orbison-styled original version.

Murray was the writer of “How Do You Do It,” the number the Beatles begrudgingly cut at producer George Martin’s request as he fretted that their own material wasn’t strong enough. He wanted that polish; they wanted to be true to themselves and not lose face before they’d even started.

The Murray song would have been like a particularly slick ghost haunting the Beatles, who wished to be their own men on the march, not representatives on behalf of someone else’s perfectly capable—but also rather rote—finesse and style. Gerry and the Pacemakers would have no problem accepting the Murray offering—and it is a sprightly tune—but Mr. Marsden and crew were a different kettle of Irish Sea fish than these Beatles, a band with a distinct code of aesthetic duty and conduct.

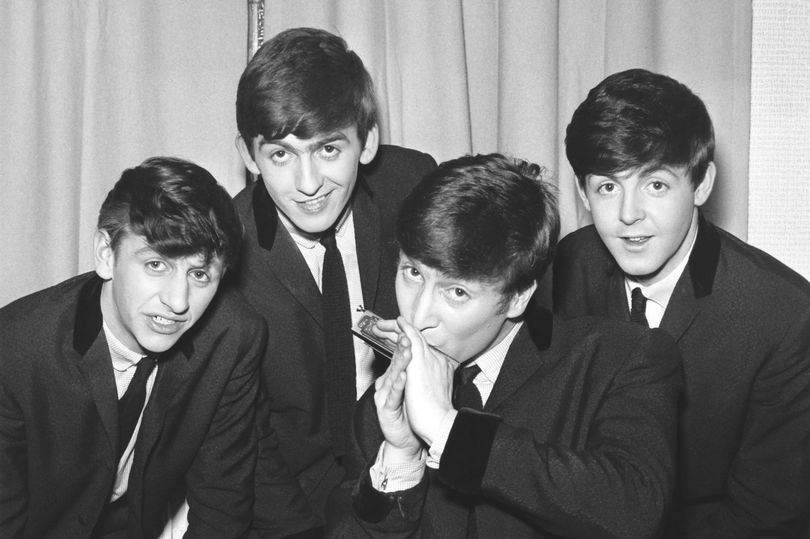

They had strictures about not selling out, nor allowing themselves to be perceived as what they thought of as soft, insofar as their music went. Whether they sold out by exchanging their leather garb for matching suits and playing the somewhat-cheeky but mostly-cute teenybopper icon roles isn’t relevant to a band for which the music was everything. Or, put it this way—without the music, there was nothing.

You do something that you were born to do for the first time—in an official, commercial capacity—and you want it to matter as both a work and an indication of what you, the artist, are about, be it a book, film or record.

“Love Me Do” is tantamount to the Beatles’ musical categorical imperative. They had to do “Love Me Do” over “How Do You Do It” because “Love Me Do” was who they were: the young men who rode on buses, cut school to smoke and listen to Elvis, played in skiffle bands, taught themselves various instruments, and applied an amateur’s approach to music-making as they were evolving into autodidact wizards of songwriting. But first, there was this initial single, which is tantamount to a statement of identity. We cannot overstate its importance. A law was laid down, from the first commercially released musical expression.

The lyrics are less words and more part of a sound design, for “Love Me Do” is a considered—and considerable—sonic statement. We are beholding sound as the persona of a collective put in audible evidence. As more than a song. You can call it a single, but it’s also a way of being, musically speaking.

The harmonica John Lennon plays on the single had been nicked from a store in the Netherlands on the Beatles’ first trip to Hamburg. Suffice to say, this instrument had seen some things. The song is primarily McCartney’s, dating to a period of sufficient vintage that Lennon referred to it as the time before they were songwriters, an apparent amateur effort that was carried forward into the professional realm.

“Love Me Do” is similar to McCartney’s “When I’m Sixty-Four” in this regard—songs that have a strong element of the busker wishing to get a sing-along started at the bus stop, or music for when the amps stopped working and the lights went out with which a band could carry on. One number simply happens to start the Beatles’ official career; the other comes in the middle of the middle of it, occurring near the mid-point of the record that represents their highest ascent within the pop culture zeitgeist.

Make no mistake: this isn’t pop. It’s not even really rock and roll. It’s the Beatles doing British rhythm and blues, with Liverpool dockside toughness and a drizzle of skiffle—or a post-skiffle progression. The Beatles had a lot of help in their rise, but the music was all them, with eight ears open to what George Martin might have to say.

Martin had a yen for the harmonica stylings found on discs by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, which Martin used to issue. The nostalgia angle couldn’t have hurt in swaying him to opt for “Love Me Do” over “How Do You Do It,” but there’s nothing nostalgic about what the Beatles were up to.

Lennon channels a dollop of Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby,” in which the harmonica riff by Delbert McClinton (whom Lennon importuned for tips) was both the song’s melodic engine and its legato hook, but his playing is as idiosyncratic as his singing was. If Lennon made a noise, be it sung, on the rhythm guitar, some words in conversation, or on his purloined harmonica, you knew it was Lennon.

Martin deemed the drumming a problem. We can go back to the pre-Ringo Starr iteration of the Beatles with Pete Best on drums on June 6, 1962, and hear the latter trip all over his kit during the song’s middle eight section on an earlier attempt. Best was fine—even, in fairness, a driver of the beat—in March during the band’s first BBC session, but he’s done in by the middle eight of “Love Me Do.” The other Beatles could be cold and also cowardly, given that not one of them had the decency to let Best know that they preferred to move forward without him. He was an albatross to be shot out of the sky, though—nothing would be allowed to undercut the band’s chances within the recording studio environment.

Nor was Martin placated when he heard Starr drumming on the song on September 4, and thus brought in session drummer Andy White a week later for another kick at the “Love Me Do” can, with Starr relegated to tambourine. That must have been musically emasculating; here’s this guy, having joined the band the month before, and already he’s on the sidelines while his three mates get to work together and make what all of them must have hoped was a first official rush at stardom.

It’s Starr’s version that ends up as the single, with White’s on the first LP. The latter is tighter—there’s more lope in Starr’s groove—but it’s not tighter by much. Play either of them and then the other for someone, and if they’re not listening carefully, they’re apt to think you pressed the repeat button.

Martin’s other issue—and one that it was hard not to have—was that John Lennon stuck his harmonica in his mouth and began wailing away right when he, or someone, was supposed to be singing the title phrase.

The solution: have Paul do it. We might think this is some small moment, but it’s huge. The Beatles were John Lennon’s band. The primary singer, at this junction, was Lennon. There would always be a certain amount of deferment to the de facto leader. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Lennon plays the final guitar solo on the final song of the final Beatles album at the end of “The End”? He saw that as his privilege, and McCartney and George Harrison were still going along with it then, so imagine where matters stood in the middle of 1962.

McCartney steps to center stage; it’s his big, “Hello, I’m Paul,” moment. We can hear a touch of nerves. You want to impress your band mates, you want to impress Lennon and not let down the side, you want to impress George Martin, you want to nail something special for posterity, for the record-buying public, and strike a blow for English beat music and rhythm and blues on behalf of a band that was doing the near-unthinkable at the time: using their own material.

His voice pairs perfectly with the chug-a-chug rhythm, the Liverpool variant on the Bo Diddley beat. Listen to how hard the guitarists strum on “Love Me Do.” The same happens with Lennon’s driving rhythm guitar throughout the A Hard Day’s Night album. That’s the skiffle, which is also a homespun sub-genre we’re already moving well past, despite the discernible elements.

The harmonica is used again on the band’s next single, “Please Please Me”—and the one after, in “From Me to You,” with liberal B-side usage as well—but the harmonica of “Please Please Me” has more of a carillon intonation coupled with the chiming tinkling of a celeste. Harrison’s guitar utilizes a bell-like peal itself—his ornamental fills help make the song—and harmonica and guitar work in symbiosis, in essence “singing” together, as Lennon and McCartney so often would, and as they did on “Please Please Me.”

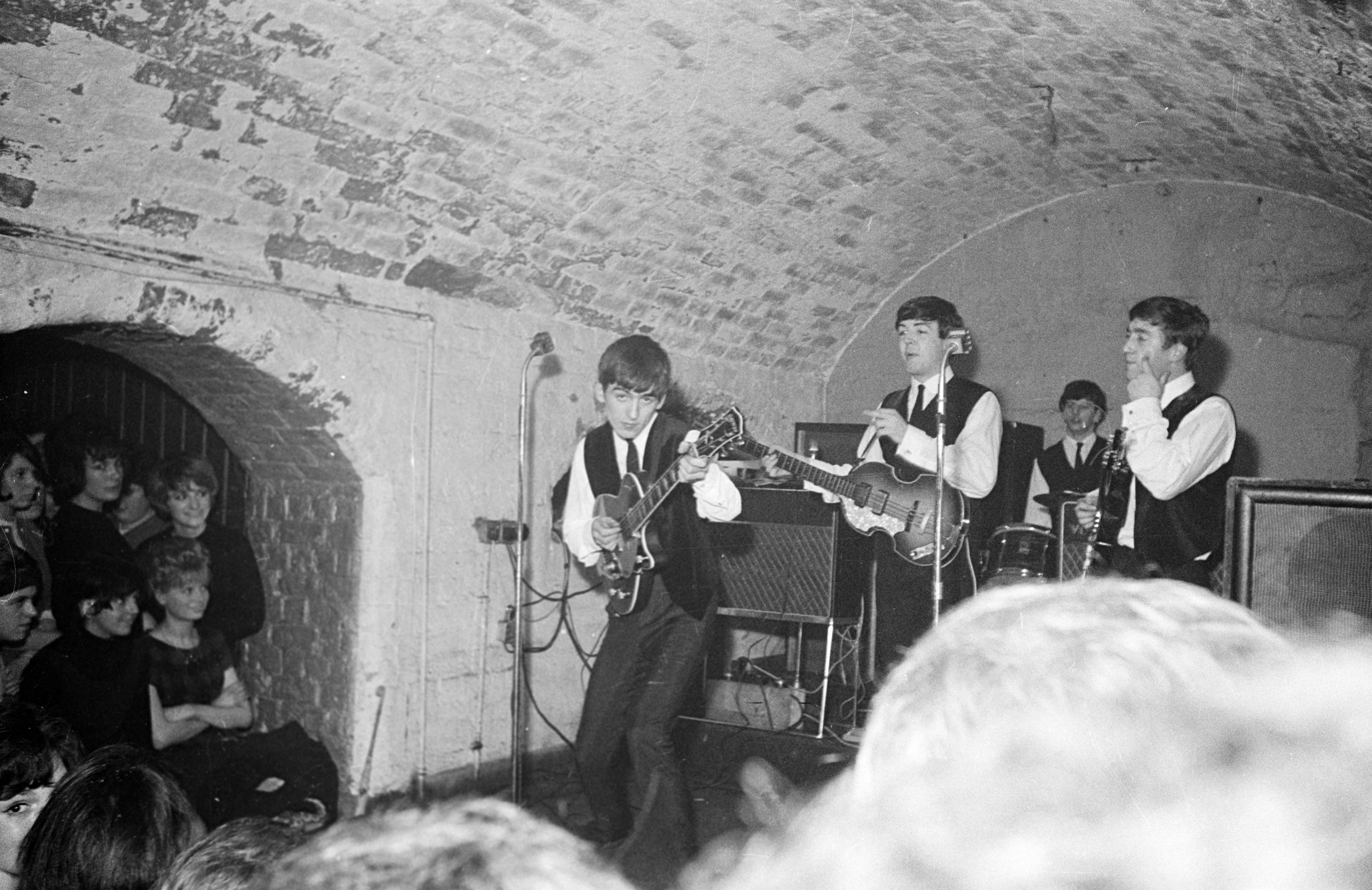

The harmonica riff, meanwhile, of “Love Me Do” seizes and tugs; it takes you with it, to wherever we’re going: back to someone’s house to cut school and delight in some boss sounds; to the Cavern Club where a new form of excitement is building; to the eventual Toppermost of the Poppermost. You pick the place, “Love Me Do” seems to say. It’s less a song than the sound of identity.

In writing, we talk about voice; “Love Me Do” has voice, and that’s not referring to the quality or quotient of the vocals or the language therein. This is idiomatically the Beatles. Now, that will prove to be a wide idiom, with much play within it, but you always know it’s them, and “Love Me Do” was the first time—the announcement—that it was that way and a keen, prescient listener might surmise it would always be that way.

Related: The story behind another early Beatles single

That spiritedness drives everything about “Love Me Do.” We don’t talk about it as one of the great singles, or even one of the great debut singles, but perhaps that’s because it transcends the normal categories, just as the Beatles themselves defied expectations and were in an environment where they were encouraged to do precisely that—or at least not deterred.

“Please Please Me” is obviously a song whose lyric is built around that simple and essential word of “please,” in which we make a form of entreaty that defines so much of our lives. “Please call me when you get home.” “Please pass the salt and pepper.” “Please love me.”

Entreaties were big for these early Beatles. They asked a lot of themselves. They asked a lot of George Martin, too, to do what few people ever have: employ trust and vision, or faith, or whatever one wishes to call it, with someone—some people—so clearly doing what others had not done before.

While it may not be as overt as on that second single, “Love Me Do” has a huge “please” in it, in which one syllable is stretched into four. Coincidence? Call it what you want. But it’s not such, any more than “Love Me Do” is a mere single or song. Then again, it’s not like there’s a hit chart for annunciatory numbers of unbreakable purpose.

Listen to the first version of “Love Me Do,” featuring Pete Best on drums

Now listen to the “Love Me Do” single with Ringo

And finally, the 2023 mix

When finally released in the U.S. on April 27, 1964, eighteen months after the U.K., it reached #1 just five weeks later, on May 30.

The 2023 remastered song is available on The Beatles’ “Red” album in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

2 Comments

Having intervied them myself, and working on a book about them myself, İ totally agree and applaud Colin’s centering on the truly unique character of “Love Me Do”.

İ could add a few things, but İ better just stick to one I’m using. Macca has said, and repeated fairly recently, that the problem with the Harmonica on “Love Me Do” was that it cuts in before John (who originally sang lead) finished singing his line. So Martin said “Paul, you’ll have to sing it.” Paul said he was incredibly nervous, cutting the single, and he would have to drop his voice down into John’s range, and nail it. This was not the later Paul who could confidently wrap his voice around any melody, or harmony. He said that he can hear the shakiness in his voice as he sings the single version. He was scared.

İf you listen to that version with Ringo on the Past Masters single version, you can clearly hear his voice go in and out of pitch, and tremble as he searches around in John’s lower range in the ” Love Me Do” part of the chorus. İt’s arguably his most ” off” and weak vocal on any Beatles. tune.

When we get to the Andy White version from the album, with Ringo angrily bashing away at the tambourine, almost drowning out White, Paul now has his vocals a bit more in hand, his pitch is still not perfect, but it’s much steadier than on the single version.

And yes Ringo was truly mad at Martin, the latter told me in 1999 ( İ believe, notes not here) that to that very day Ringo would bring up being shunted aside, and Martin would continue to apologize profusely to him over the years.

Copyright 2021 Victor R. Garbarini.

This article is what makes the Beatles so fascinating. ONE song rates an entire chapter (and that’s just the creation, never mind the 60 years following).

If you haven’t read the expanded (1700+ pages!) Tune In by Mark Lewisohn, you might dig that one up while we all wait for the next volume.