When announcement arrived from Apple Corps Ltd., Capitol Records and UMe that several Giles Martin-produced special editions of the Beatles’ Revolver would be released on Oct. 28, 2022, author Harvey Kubernik gathered quotes from various interviews he’s conducted relating to the album and the time in which it was created.

For more about the special editions of Revolver, visit here.

George Harrison: I didn’t know how to tune the sitar properly, and it was a very cheap sitar to begin with. So “Norwegian Wood” was very much an early experiment. By the time we recorded “Love You To” [for Revolver], I had made some strides. The sitar is an instrument I’ve loved for a long time. For three or four years, I practiced on it every day. But it’s a very difficult instrument, and one that takes a toll on you physically. It even takes a year to just learn how to properly hold it. But I enjoyed playing it, even the punishing side of it, because it disciplined me so much, which was something I hadn’t really experienced to a great extent before.

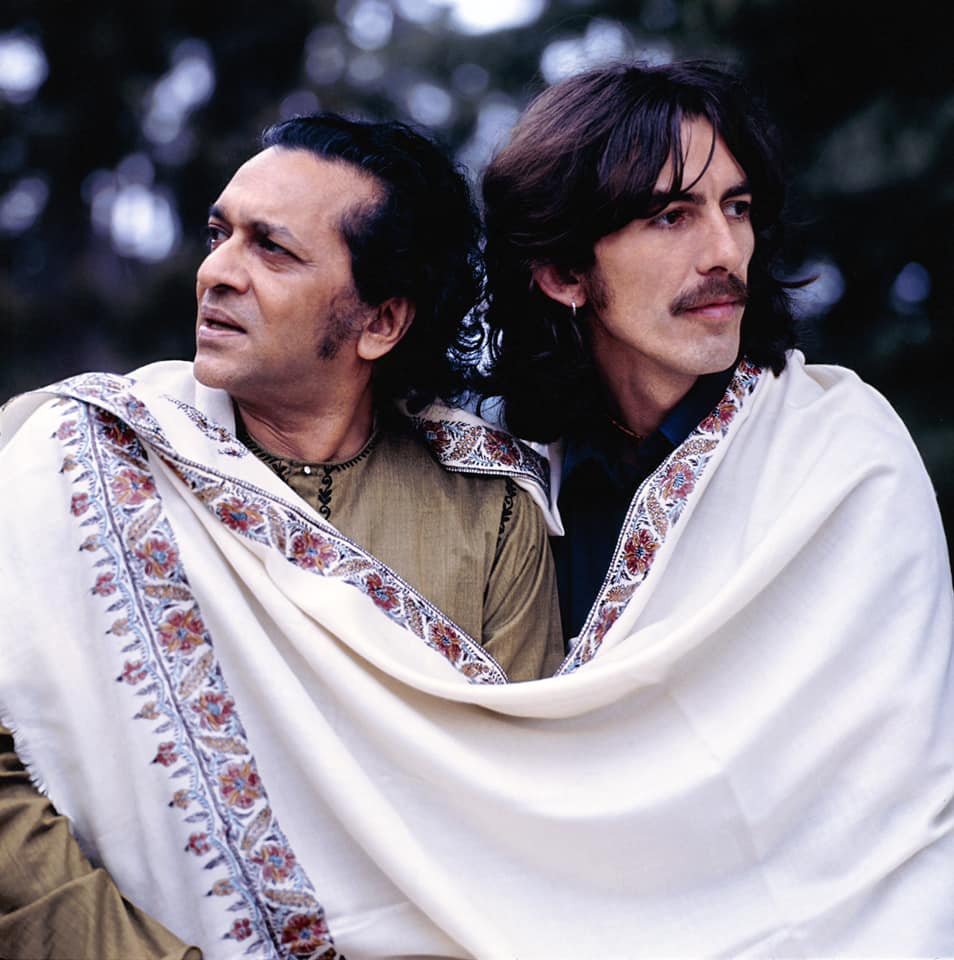

Ravi [Shankar]’s music was the reason I wanted to meet him. I liked it immediately; it intrigued me. I don’t know why I was so into it. I heard it, I liked it and I had a gut feeling that I would meet him. Eventually, a man from the Asian Music Circle in London arranged a meeting between Ravi and myself. Our meeting has made all the difference in my life.

Everybody in the band was very open to bringing in new ideas. We were listening to all sorts of things: Stockhausen, avant-garde music, whatever, and most of it made its way onto our records.

I realize the Beatles did fill a space in the ’60s. All the people the Beatles meant something to have grown up. It’s like anything you grow up with—you get attached to things.

I understand the Beatles in many ways did nice things, and it’s appreciated that people still like them. They want to hold on to something. People are afraid of change. You can’t live in the past.

Ravi Shankar: George is a very rare person. It is something so special. There are many other people who could do what George does, but they don’t have that depth. He’s so unusual. What has clicked between him and me, what he gets from me, and what I get from him, that love and that respect and understanding from music and everything, is really the most important thing. It’s not the money, or him helping me to record, that’s not the main thing. But it’s the very special bond between both of us.

My work…I can only tell you what I’ve heard, not once, but a thousand times. It comes from a Black man who is a porter at the airport, or the immigration officer, and they say one thing, which I always get tears in my eyes: “Thank you for what you gave us through your music.” Some go back to the ’60s, and this has always been the case. That’s what I want to do through my music: to give them, as much as is possible, love and peace and the feeling of all the different sentiments that we have, starting from romantic to playful, to happiness, to speed, to virtuosity and fun. And finally, something which is most important to me, the spiritual.

John Densmore (The Doors): George Harrison came to one of our recording sessions for The Soft Parade at Elektra Studios. He said all the extra musicians on our session looked like [a session] for Sergeant Pepper’s.

[In 1967] Robby [Krieger, Doors guitarist] and I went to see Ravi [Shankar] play at the Hollywood Bowl, and George was on stage. We had been students at his Kinnara School of Music. Ravi didn’t teach at the school, but he’d drop in and give a little lecture on Sublimating Your Sexual Drive Into Your Instrument.

For some reason, in 1965 Robby and I went to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation Center in Los Angeles because LSD was legal and we were quite interested in our nervous systems, and knew we had to do this TM thing slowly.

We went over there and I met this little guy, Maharishi, and the love vibe was very palpable. TM was the reason the Doors were together. TM glued together myself, Ray [Manzarek], Robby and Jim [Morrison].

So maybe 1966, 1967, I was noticing in the traditional Indian ragas you gotta wait for your climax. It’s not a quickie, you know. Sound-wise, “The End” was a raga tune. So that was the influence.

So maybe 1966, 1967, I was noticing in the traditional Indian ragas you gotta wait for your climax. It’s not a quickie, you know. Sound-wise, “The End” was a raga tune. So that was the influence.

Then, a year or two later, I read that the Beatles were into TM and our little secret was being spread worldwide. Harrison was doing it in England. Great. The whole Eastern Indian thing, Ravi Shankar, via George Harrison and the Beatles, saturated everything. You hear the Indian thing in techno stuff now. That came in and it was deep and it’s still around. We need the East.

Related: When the Beatles played Tokyo in 1966

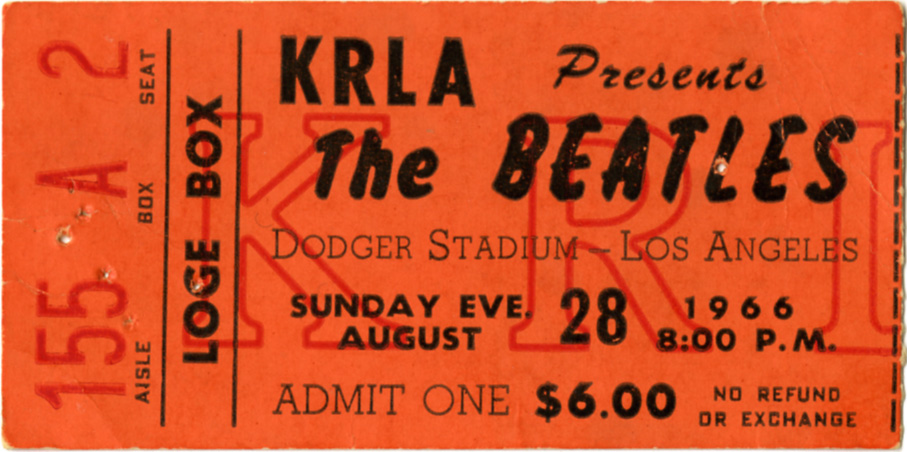

Steven Van Zandt (E Street Band): [Revolver] was extra notable by being the first album to have three George songs while we in America, as usual, lost three of the coolest tracks [that were on the U.K. version]—“I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Song” and “Dr. Robert,” the second coolest after “She Said She Said”—as the American company continued to turn every two albums into three. They [the Beatles] wouldn’t decide to stop performing live until the next disastrous tour a few months later, but they may have had a premonition at that point, which undoubtedly opened their minds to even more adventurous artistic exploration.

Related: Our look back at Capitol’s decision to issue different Beatles releases in the U.S.

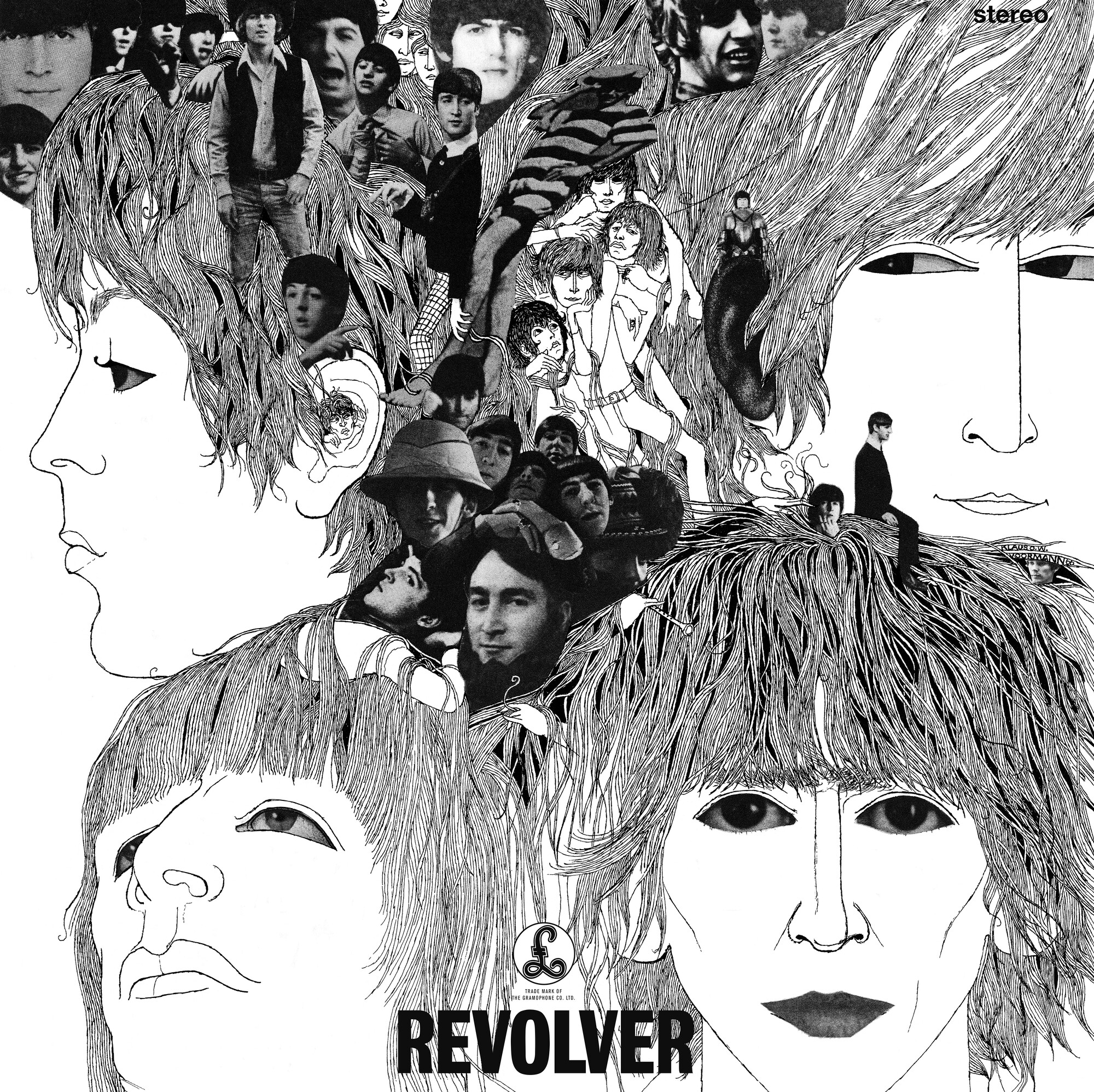

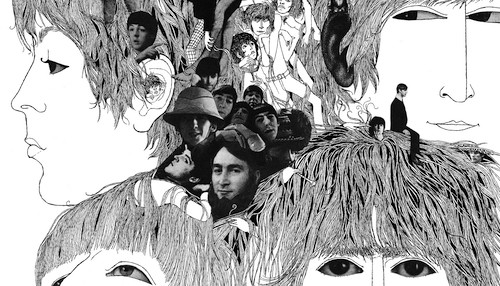

Clem Burke (Blondie): As I sit here in my office listening to the Beatles’ album Revolver on my laptop while holding the vinyl in my hand, it occurs to me that just by looking at the cover art you already knew the LP would be different, and it was! As much as Rubber Soul influenced everyone from Brian Wilson to the Byrds and on, Revolver was the real experimental leap forward for the Beatles. Here is where they really began singing about things other than love and girls. Songs like “Taxman,” “Eleanor Rigby” and, yes, “Yellow Submarine,” were taking their inspiration from a very different place. Both lyrically and musically they were provocative, and who exactly was “Dr. Robert”?

Having Ringo play along to a tape loop for “Tomorrow Never Knows” was extremely inventive and unheard of at the time, not to forget the use of horns and strings and sound collage as well. This is the Beatles’ pop art album, from the multimedia cover to the eclectic points of reference in the sound and lyrics. It is in my opinion things were about to change not only in music but in the world as we knew it.

Burton Cummings (The Guess Who): You’ve got to remember that Revolver starts with George’s “Taxman.” The album rocks hard. There were more ballads on Rubber Soul. We [the Guess Who] did a television show in 1966-1968 for the CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Company], Let’s Go. Sometimes we had to learn 12 covers in an adjacent radio studio that were then broadcast. We did “Got to Get You Into My Life.” Later I sang “Yellow Submarine,” complete with a megaphone.

Kim Fowley (Producer): In 1966, I spent some time with John and Paul in London. Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys was in town doing advance publicity for the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and had an acetate pressing with him. I was asked to bring the Who’s Keith Moon over, who brought John and Paul to the hotel room. They were both very impressed by the recording, left the hotel and went into the recording studio the next day and did “Here, There and Everywhere” for Revolver. Both of them were able to digest and gauge the whole essence of Pet Sounds in one listening.

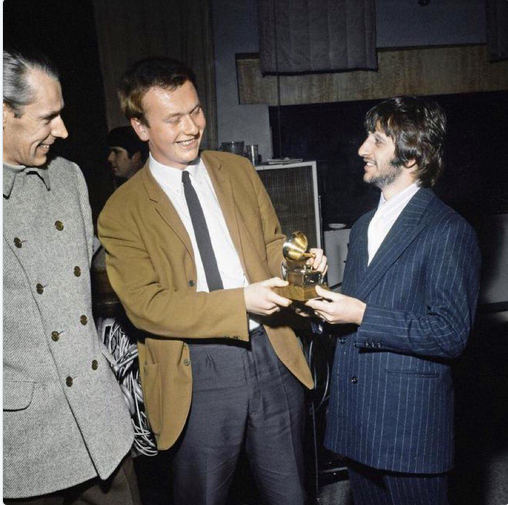

George Martin was the catalyst for the embryonic dreams of Lennon, McCartney, Starkey and Harrison. Martin was able to consolidate and expand their anticipation. He was a great editor.

Related: What were the top U.S. radio hits of 1966?

Dr. Timothy Leary: I have always been fascinated and obsessed with music. I was in the first generation of kids that had radio to listen to late at night. So it’s been music all the way. We were futurizing: What’s the next thing? What’s coming? The Beatles’ album Revolver and especially Sgt. Pepper, everybody knew about it. In there is a tangible culture. People are sharing this information. Suddenly every city had its counterculture radio. Spread that word!

Geoff Emerick (Beatles’ engineer): “Tomorrow Never Knows” was the first session I did on Revolver. I hear music in colors. Bass and drums are always my favorite and just building stuff around that, from color textures in my head upon what’s happening in the studio.

Roger Steffens (Author and archivist): More than any other record of the time, Revolver was responsible for turning millions of people on to LSD. If you wondered what a trip would be like, all you had to do was put on earphones and close your eyes and wonderment abounded. Stunning new instruments inserted into the pop panorama: harpsichord and tablas and sitars and tapes spun backwards into a Delhi rave-up. Prompting acidic reflections, feeling hung up but not knowing why, who cares as long as we can drift in this pill-shaped undersea craft and maybe find some of that Sunshine acid, John closing it all out in his submarine skipper voice. No doubt this is their finest most consistent and innovative work, a quantum leap forward.

Bill Mumy (Actor): Revolver changed everything, again, as the Beatles had been doing on a regular basis for a few years already. I bought the album for $2.83 from Do Re Mi Records on Pico Blvd in West L.A. I rode there on my purple Schwinn Stingray bike. The Klaus Voormann album cover was stunning and led to hours of close inspection. The photo on the back, of the Fabs all wearing sunglasses, was somewhat spooky yet full of positive vibes at the same time. Those drum sounds! The punchy bass sounds! The swirling vocals and biting guitars. George Martin’s arrangements and production… All fab to the max.

Bill Mumy (Actor): Revolver changed everything, again, as the Beatles had been doing on a regular basis for a few years already. I bought the album for $2.83 from Do Re Mi Records on Pico Blvd in West L.A. I rode there on my purple Schwinn Stingray bike. The Klaus Voormann album cover was stunning and led to hours of close inspection. The photo on the back, of the Fabs all wearing sunglasses, was somewhat spooky yet full of positive vibes at the same time. Those drum sounds! The punchy bass sounds! The swirling vocals and biting guitars. George Martin’s arrangements and production… All fab to the max.

But it really boils down to the songs. I can’t think of another album in history that has better ones! To this day, it shines as a brilliant project by the greatest and most magical band in the history of the universe! It is, in my opinion, quite probably the best album ever made.

Harvey Kubernik’s book, It Was Fifty Years Ago Today (The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood), was published in 2014 by Otherworld Cottage Industries.

1 Comment

Who doesn’t love “Revolver?” But I found so many of these comments especially interesting from Americans, for as Little Steven pointed out, we here in the USA initially received an amended version of this masterpiece, which in itself was a travesty upon The Beatles creativity and art. It may be difficult for modern music lovers to comprehend, but LPs of that era were conceptualized and created to be listened to as a whole, rather than in random, disjointed cuts, which is essentially what Capitol records did with The Beatles LPs up until Sgt. Pepper. This created a whole different listening experience for American record-buying fans, and, tragically, not one that The Beatles themselves had intended. It wasn’t until many years later when LPs were reissued on CDs that American audiences received The Beatles LPs on CD in the form and order that they were intended. And for many devout listeners, like myself, it was a somewhat disorienting experience. So much so that I understand that many American CD buyers were clamoring for their Beatle albums in the original breakout LP forms and track listings they had originally received them in (LPs with titles The Beatles themselves actually never made), as these were the forms that they knew and loved these records as. All this to say, it’s kind of fascinating to hear accounts of what “Revolver” meant to so many, like Bill Mumy here, when in fact, we weren’t listening to the actual “Revolver,” as it was created, at all. Thanks Capitol Records! I wonder which version American musical celebs like Brian Wilson were hearing? Did these folks even know there were different American versions back in the day?