If one is familiar with the history of the Beatles as young men—and even as pre-Beatles boys—it’s hard to think of the “lads” as ever having possessed much in the ways of innocence. They were seemingly seasoned in life from the first, on account of where they grew up, the circumstances in which they did this growing and what they had lost and endured.

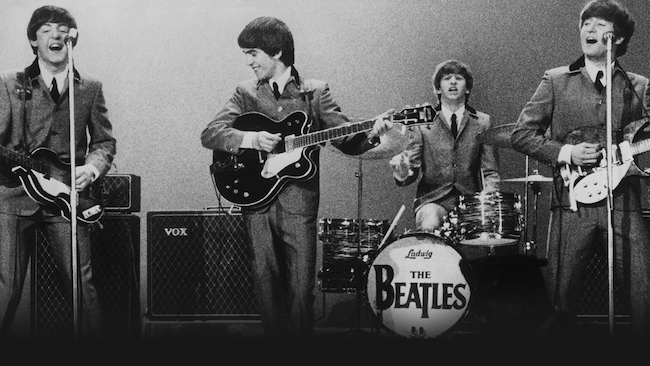

In the throes of Beatlemania, in 1963 and 1964, before a shift to mature, “confessional” songs in 1965 such as “Help!” and “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” the band’s image—and one they worked to cultivate—was that of cheeky innocents. They cracked wise, but not too wise. A Rolling Stone would be itching to make of your daughter a sexual conquest, whereas a Beatle was hip enough to be cool, but not so hip that they wouldn’t be respectful in the front parlor with the parents before heading out to the pictures. John Lennon’s 1962 marriage was hushed up, as best as manager Brian Epstein could manage, the thinking being that if the fans knew Lennon was off the romantic market, the boys would face a dip in appeal.

These are quaint concerns now, but we’re also talking about a band that became as big as a band possibly can, and then collectively worried that they might be finished after deciding to give up touring, because that’s what a group did. They went out on the road—even if the road meant to the small club the next town over—and played, be it to five people or 50,000. Still, loving The Beatles is a cultivation of one’s own form of innocence, at least at some point or other, and most likely early on.

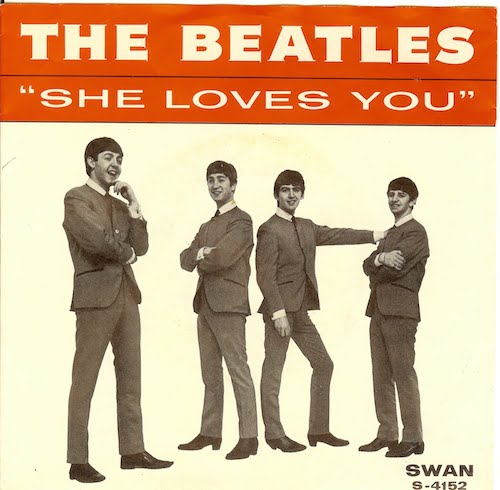

You start listening to their music, and that’s done so with a freedom—an apartness—that I’d suggest comes with no other band. To fall in love with “She Loves You,” A Hard Day’s Night and “Hey Jude” is to embrace a series of sounds that register as autonomous, cut apart, sans overlap with anything else. Maybe with the Stones one thinks about sex, or destruction with the Who, the forbidden with the Doors, but with the Beatles the music is total, which speaks to how that music envelops us. We are sealed within the Beatles’ cocoon, to mix insect-based metaphors.

This is a reason why people are so loyal to the Beatles, and why they can treat any criticism of their work—no matter how thoughtful and/or warranted—as a personal attack or slight. They’re apt to see it as some knock against their childhood, early days, teen years, whenever it was when the Beatles bug did its biting for them, and then who they are in all of their subsequent decades, particularly when they’re older and lamenting what they have or haven’t done and wishing they could go back. The innocence is partially an illusion, and I’d suggest that when we recognize as much, and think critically about Beatles music, we allow ourselves the opportunity to enjoy it even more. You can love a flaw or a flub, which is something that few people realize and welcome, but in that truth may well be an additional, necessary, core truth of human existence.

Early Beatles music in particular resonates as wholesome, partially because of its reliance on pronouns. Think about what a huge statement the very title of “She Loves You” is: she loves you. We don’t often use a phrase like that, and in this case, a person—a friend—is letting someone else know this big thing that they might not know on their own, or that they need to be reminded of. The early Beatles were convivial, but not avuncular; they dispensed advice—or, rather, their songs featured snatches of overheard advice—but in the way of a chum, not as some lesson. The early Bob Dylan could give you a lesson. “Blowin’ in the Wind” has the quality of a poem that you’d be made to memorize in school. The Beatles’ early songs felt like they were taking you aside for a chat you needed to have, which would still be pretty painless, and you wouldn’t have to recite anything in front of the class.

Early Beatles music in particular resonates as wholesome, partially because of its reliance on pronouns. Think about what a huge statement the very title of “She Loves You” is: she loves you. We don’t often use a phrase like that, and in this case, a person—a friend—is letting someone else know this big thing that they might not know on their own, or that they need to be reminded of. The early Beatles were convivial, but not avuncular; they dispensed advice—or, rather, their songs featured snatches of overheard advice—but in the way of a chum, not as some lesson. The early Bob Dylan could give you a lesson. “Blowin’ in the Wind” has the quality of a poem that you’d be made to memorize in school. The Beatles’ early songs felt like they were taking you aside for a chat you needed to have, which would still be pretty painless, and you wouldn’t have to recite anything in front of the class.

So while I knew that the Beatles got up to all sorts of no-good on their first North American tour in 1964—and if you had a daughter, you’d probably want to make sure none of these guys were taking her out—I’ve always heard the music from that initial cross-country jaunt as wide-eyed, with a certain “aww shucks” quality. It’s similar to qualities evinced by Tom Sawyer. He’s up to what he’s up to, but the outward image is of charming and pure neophyte in all matters of life, and certainly the opening strains of adult life. A good kid. It was on that first tour that the Beatles were trying to the best of their abilities most nights. They would go on to play stellar shows in 1965—the Shea Stadium gig is a doozy, and they tore it up in Paris—before largely transitioning to discontented butchers in 1966, with a night’s exception or two, but with any bootleg from 1964 I’ve had the sensation when listening that they honestly didn’t know if they’d ever have the chance to do what they were doing again. So they went for it. In good faith, as much for themselves as their audiences.

That’s why I love the tape of their show from Vancouver’s Empire Stadium on August 22. The fidelity is excellent, and though the performance doesn’t have the professional polish of the Hollywood Bowl show, to me it’s more representative of the Beatles out in the field. The Hollywood Bowl was posh, the market elite, whereas, at Vancouver, we get the Beatles as road band.

Related: Read our review of the Hollywood Bowl album

This was one of the earliest bootlegs I owned, and the setlist alone was enough to make me swoon. Setlists can be that way. For instance, when I saw what the Yardbirds played at L.A.’s Shrine Exposition Hall in late spring 1968—nuggets from their catalog like “New York City Blues” and “I Ain’t Done Wrong,” with Jimmy Page on lead guitar, and a cover of the Velvet Underground’s “Waiting for the Man”—my mind was blown before I heard a note, and then it was blown all over again when I did.

The Beatles’ Star Club tapes are similar, but that 1964 setlist was perfect. You got “She Loves You” and “All My Loving” from the relative early days of the year before—a trick of the space/time continuum that’s a reality of Beatles-based temporality, which had its own private time zone, because “last year” might as well have been 50 years ago; a song that already felt like a rarity in “Things We Said Today,” key hits from A Hard Day’s Night, a Shirelles cover in “Boys” so that Ringo Starr could get in on the vocal proceedings, and a storming “Long Tall Sally” to cap it all, which at the Hollywood Bowl may have featured the most exciting guitar solo George Harrison ever played.

The Beatles took to the stage just shy of half past nine, at which point 20,000 Canucks went as wild as you would have expected them to go. Local radio station CKNW broadcast the affair, and thus we have the quality of surviving tape that we do. I always loved the between-song chatter, especially from John Lennon. You’ll note that in 1965, that chatter has a world-weariness to it, a sardonic edge that moves from the playful to a realm of discontent, an attitude of “Do we really have to be doing this again?” I cherish any live version of “She Loves You,” because though the Beatles didn’t gig for an extended amount of time, it has always seemed like “She Loves You” had a particularly short shelf life as a concert offering. It’s funny the associations we make, because “She Loves You” was performed again and again on the BBC, but it’s just that I have such a hard time imagining the mere possibility that it could have been sung by these same men in 1965, and can you even conceive of them playing it—this, the representative song of their ascent—in the year that would see the release of Revolver? I don’t think the Beatles composed a more sophisticated work of art than “She Loves You.” But it belongs back in an earlier chapter, where the innocence was writ large, if not as outright truth.

Listen to the entire Vancouver Beatles show from 1964

The BBC recordings contain much of their appeal in the byplay of these men, the conversational sound of their bonds. Those bonds are in turn a huge part of the music. If you make something that the people you care about care about, there’s a great chance that other people will be able to care about it as well, and that still goes if the people you care about are also the people who make whatever it is you’re making with you.

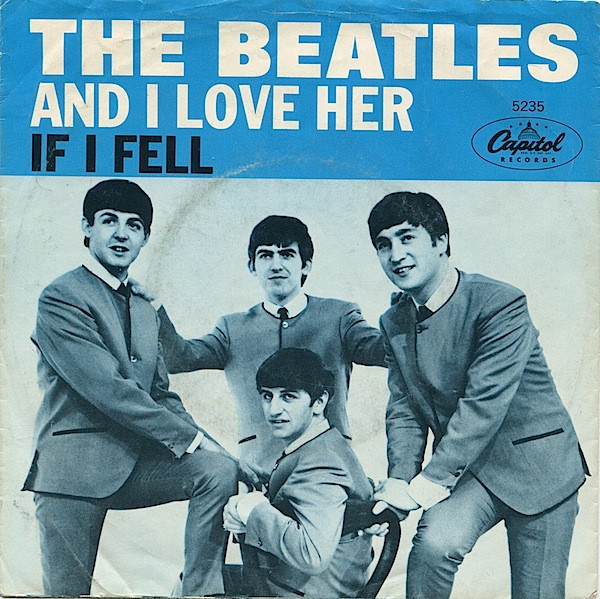

That brings us to the Vancouver performance of “If I Fell.” The song is typically deemed a love song, which is odd, considering that it’s about a singer who wants to use someone else in order to make another person he cares about more feel pain and jealousy. Emotionally, it’s barbaric in that fashion. I’d maintain that it’s nastier than anything Dylan ever wrote, including “Positively Fourth Street.” The way it’s sung, though, softens the intent, but that’s also how we manipulate people; we sell them a proverbial bill of goods, best we can. We’re looking out for us, not them. And that’s how we hurt people the most.

That brings us to the Vancouver performance of “If I Fell.” The song is typically deemed a love song, which is odd, considering that it’s about a singer who wants to use someone else in order to make another person he cares about more feel pain and jealousy. Emotionally, it’s barbaric in that fashion. I’d maintain that it’s nastier than anything Dylan ever wrote, including “Positively Fourth Street.” The way it’s sung, though, softens the intent, but that’s also how we manipulate people; we sell them a proverbial bill of goods, best we can. We’re looking out for us, not them. And that’s how we hurt people the most.

There are moments when certain individuals sing together that the extent of their friendship—the love of that friendship—pulls you in, such that you’re all but a part of it yourself, until the moment—the song, in this case—passes. The Beatles have a number of these examples, and they’re always oriented around John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Think about the duets on “Hey Jude” and “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” for instance, and how they occur when a song’s narrator needs the support of a true friend.

“If I Fell” is normally cited as a duet, but it begins with Lennon all alone for a passage in which he has to hit a note that is just out of his range on most nights, with the line “and help me.” That “me” is tricky. It’s the Lennon variant of the famous high note in “O Holy Night” (“Oh night/Di-vine”). On the A Hard Day’s Night LP, he gets there, and then McCartney enters to join him, as if he’d been waiting in support and knew his partner could do it all along. The romance of the song is in their paired voices, not the singer’s plan of revenge, with this new girl caught up in his scheme. The scheme isn’t necessarily that dastardly either, so much as it’s thoughtless. The singer isn’t trying to hurt someone else, but his own heartbreak—or humiliation—has overwhelmed him and he can’t see who else he might be negatively impacting.

That’s a real piece of writing, allowing that Lennon wasn’t merely plumbing his own life with an assist from McCartney. The version of “If I Fell” in Vancouver has long been known as the laughing version of the song, because the challenges of singing the piece—and missing notes, muffing words—causes Lennon and McCartney to keep cracking themselves up. You know how that goes. You try to control yourself, and the more you try, the more hopeless it becomes. Shades of Lennon and his friend, Pete Shotton—who was Lennon’s comrade version of McCartney before Lennon knew McCartney—at school as a boy, before the inevitable caning courtesy of a displeased headmaster.

Watch part of the band’s press conference in Vancouver

I wonder what one might have thought experiencing this performance in real time, with these men up on the stage, doubling over with laughter, but somehow singing in a winning manner all the same. I bet you would have thought they were more flesh and blood, more outrightly human, than you’d been led to believe—and let yourself believe—up until then, with that prevailing innocence of which I’ve spoken. They were blokes. Dudes. Guys. Buddies. The Beatles could make it appear that they were part of your group, but also apart in their own world, which is what I hear on this tape. I used to laugh with my friends that same way, and so has everyone, but the Beatles’ form of this is not your form and vice versa, and so we have both the notion of community and individuality. To gain ingress into the Beatles’ “gang”—be it on the BBC sessions or with this tape from Vancouver—was to paradoxically cultivate whatever it is that marks your side of the street, your emotional home.

I think that’s invaluable, and it’s most prevalent with the Beatles during these years of innocence that also are not so innocent. But you also experience it with “Strawberry Fields Forever,” that idea of being taken somewhere, be it down or back. Childhood is at the fore, and the innocence of childhood, but that’s really about a way of thinking. Experiencing the world with that wide-eyed quality where everything is allowed into consideration. Tom Sawyer would get that. The laughing Beatles of this 1964 Vancouver night would get that. We listen ourselves, and we get that. It’s a good thing to get, the idea that there’s wisdom in innocence, and innocence in wisdom. The early Beatles were excellent teachers because they were also the students—an idea both well worth a laugh and a signaling nod of understanding.

Listen: The chaos of the Beatles’ first Canadian concert was broadcast live on a local radio station

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024