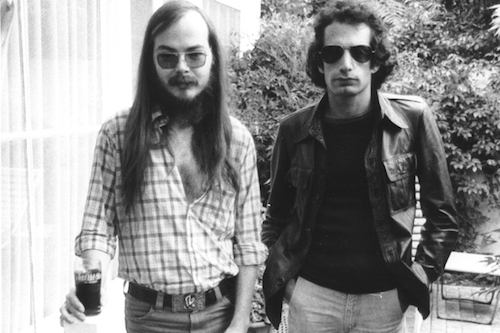

Future Steely Dan keyboardist/vocalist Donald Fagen and bassist/guitarist Walter Becker met at Bard College in upstate New York in the ’60s. The aspiring songwriters shopped their tunes in the Brill Building and found a sympathetic ear in Kenny Vance of Jay and the Americans fame; the pair then toured in the the group’s backup band on the oldies circuit while Vance helped develop their sound and oversaw early demo recordings.

In late 1971, Becker and Fagen moved to Los Angeles and Steely Dan was formed the following year, lifting their name from William Burroughs’ book The Naked Lunch. That same year, the debut Steely Dan LP, Can’t Buy a Thrill, a direct lyrical lift from Bob Dylan’s “It Takes a Lot To Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry,” hit the airwaves and the record stores. Their success was swift, and, for the next few decades, never wavered.

[Steely Dan’s classic ABC and MCA Records catalog is returning to vinyl with an extensive yearlong reissue program of the band’s first seven albums, which is being personally overseen by founding member Donald Fagen. The series kicked off in Nov. 2022 with the album that started it all, 1972’s, Can’t Buy A Thrill, featuring the band’s breakthrough hits, “Do It Again,” “Reelin’ in the Years,” and “Dirty Work,” with original lead vocalist David Palmer. They’re available to order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Today, Fagen continues leading a version of Steely Dan following the 2017 death of Becker.

These interviews with Becker and Fagen were conducted at various stages of their career.

Interview with Walter Becker (conducted for HITS magazine in 1999)

Q: Steely Dan quit touring very early in your career, concentrating on songwriting and studio work. Then you and Donald split in 1981, took a long break and then reunited. So most of those in your audience today know you pretty much exclusively from radio exposure, reissues and the Citizen Steely Dan boxed set.

Walter Becker: For better or worse. A big bulk of the tunes that we are doing in concert we never performed live. So, we’re doing them live for the first time and that kind of gives it a little bit more of a credible recreation of something it might be.

Maybe you have the best of both worlds. The people who come already know the music, and now they’re discovering the players and the voices. They are here for the music and then the person.

Well, that’s kind of neat. We were probably successful in what we were trying to do in the ’70s at projecting a musical persona that was not particularly tied to one or two or five individuals. That was rather an outgrowth of our writing and recording style. There is this bit of curiosity that is out there.

Have the songs become even more rewarding because they have now stood the test of time?

It’s funny, but that kind of thing probably happens more for listeners than for us playing them. We selected new songs we had never played before. And of the songs we had done years ago, we tried to diddle with them a little bit so that we’d feel fresh to play them. When we’re actually doing it, that’s probably not so much the case for us than for people in the audience.

Touring seems easier for you now. I remember the gigs in 1974. Back then the songs seemed rushed.

Then, even on our best nights, it was this out of control kind of thing.

Watch them perform on The Midnight Special a year earlier

You told Venice magazine, “Donald and I were trying to do this well-orchestrated thing, and we had these wild men we were doing it with, including ourselves.”

Everybody was, uh, distracted by other elements in the traveling musician scenario. The thing is, today, the scale at which we are doing it now makes it possible to call the shots in a much better way, and to plan things out. And the business of doing this has evolved to the point where it is very much a known technology and procedure. Everything has improved.I like playing live. It’s great fun, especially in this kind of context where basically everything is done for you and you kind of waltz in, and everything is pretty much perfect.

You’ve been a staff writer, you wrote for the band and for your own solo work. Are the disciplines the same?

I think the basic tools are the same and the basic skills are the same. And it’s been such a long time since I tried to write songs for other people. I think about doing it sometimes and I may sit down to try and do that again just to see what happens. But generally speaking, I don’t know how that would be again. Basically, it’s the same thing if you’re writing songs, trying to put together the pieces of the song. [When writing for a solo album] My first dilemma was, how do I go about writing by myself, that is, without Donald?

In our collaboration, he provided a lot of the harmonic direction and overall tonal framework, and his ability to develop great chord sequences, striking modulations, and so on, became an essential ingredient in our writing style. I decided to use a minimalist approach that would enable me to focus on the overall thrust of the song, rather than bogging down in harmonic complexities and ornaments that were perhaps irrelevant in the musical context of the day. When you’re collaborating, you often need to persuade your writing partner that an idea is interesting enough or strong enough to work with, and sometimes this is difficult or impossible to don.

When you’re working alone, you get to follow your hunches a lot more. I also took advantage of events unfolding in my immediate environs as subject matter for songs in a way that was somewhat different from what we used to do. Generally speaking, I tried to suspend my critical perception of what I was doing, musically and lyrically until I had completed something, so as to range out a bit into new areas. This experimental approach was helpful in maintaining a flow in my writing.

When you were staff writers, did you ever think you and Donald could survive and flourish as bandleaders in the record business, as a performing group playing original material?

I think when Donald and I started out we were arrogant enough to think we would be successful, in spite of the fact that what we were doing was as far off the beaten path as it was. And so, we kind of had enough confidence in what we were doing to keep at it long enough until we prevailed, so to speak. Certainly, it would be hard to imagine that we are still doing this and events have taken the shape that they have, so many years later. It’s quite surprising. Obviously, for Donald and myself, the primary thing, the focus all those years, was records and radio.

Portions of the 1977 interview below with Fagen and Becker, for radio station KPFK-FM, were published previously in Phonograph Record Magazine.

Tell us about the album you’ve just finished.

Tell us about the album you’ve just finished.

Donald Fagen: It’s called Aja, which is the name of a Korean colleen, if you will. We started it about a year ago. These things take a long time.

Why?

DF: I don’t know. I guess maybe we were too leisurely about the pace, although it seemed like we worked very hard on it. You’d think it would be pretty quick, wouldn’t you? It’s hard to play, we throw away a lot of stuff, we do a lot of stuff over, and it takes a long time.

Watch them perform a favorite from the album, many years later

Any new approaches?

DF: We fooled around for a while with digital click tracks, which is a method used quite a bit to make records that are supposed to be metrically perfect. But we decided the tunes we had weren’t suitable for that kind of treatment, so we went back to our tried-and-true method, which is basically to go into the studio and have a bunch of guys play, and that worked out pretty good.

How about the lyrics this time?

DF: It has no social significance. I think we’re steering a little bit away from melodrama. The tunes we ended up with are in a somewhat lighter vein than the last album. There’s some basically erotic material–not heavy breathing or anything, but…It’s possible that the lyrics could get sparser and simpler, because people don’t read anymore and they’re a lot dumber than they used to be. It’s always a challenge to fit certain lyrics to some kind of music or write some music that will most successfully express a lyric idea. The trick is to distill it and concentrate it so you have as few lyrics as possible…

Related: Our Aja Album Rewind

What was your most disastrous show?

DF: The one where I plunged a speaker screw about three inches into my skull getting onto the stage and bled through the set. It did give a sort of grand guignol effect.

WB: They [the audience] thought it was part of the show.

[Author Harvey Kubernik’s books on various music subjects are available to order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

1 Comment

I got to see them on their last trip out together, about a year or more before Walter died, and they were excellent. As was their opening act, a guy named Steve Winwood.