When the brothers Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb moved into Criteria Studios in Miami in early January 1975, The Bee Gees hadn’t had a hit single since “Run to Me” in mid-1972, and their recent albums had all stiffed. They were hoping to deliver their 13th album and get back on track, but at first it seemed it’d be a very unlucky number indeed. “It has become faintly ridiculous to be the Bee Gees in a world of Enos, Alices and Bowies,” wrote Jaan Uhelskzki in Creem, “But the Bee Gees were determined to bounce back in the biz like a wad of Silly Putty.”

When the brothers Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb moved into Criteria Studios in Miami in early January 1975, The Bee Gees hadn’t had a hit single since “Run to Me” in mid-1972, and their recent albums had all stiffed. They were hoping to deliver their 13th album and get back on track, but at first it seemed it’d be a very unlucky number indeed. “It has become faintly ridiculous to be the Bee Gees in a world of Enos, Alices and Bowies,” wrote Jaan Uhelskzki in Creem, “But the Bee Gees were determined to bounce back in the biz like a wad of Silly Putty.”

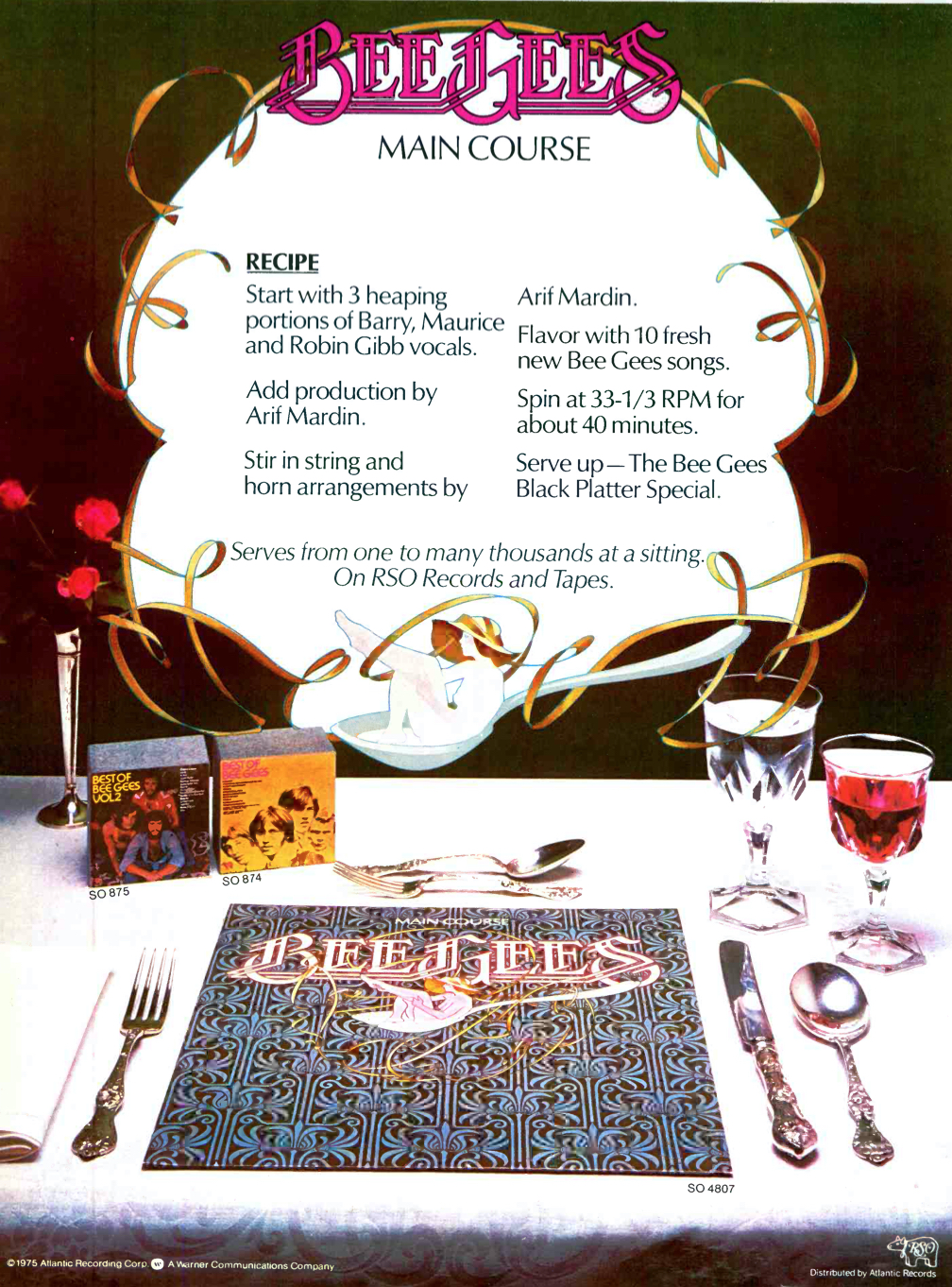

They were working with engineer Karl Richardson and producer-arranger Arif Mardin, who’d had great success with Average White Band, Donny Hathaway and a number of other Atlantic Records acts, and had helmed the previous Bee Gees LP Mr. Natural (it peaked at #178 on the Billboard Top 200 Albums chart). When their manager Robert Stigwood heard the first efforts from Criteria, “Was It All in Vain” and “Our Love Will Save the World,” recorded in their standard style, he told them to scrap them and start again. He complained the Gibbs were hopelessly out of date, and needed to listen to what current hit records were like. “I told them I would swallow the costs, not to worry, but they really had to open up their ears and find out in contemporary terms what is going on.” Robin remembered it as a very bad time: “We were in a real dead zone. No one wanted to hear us. The record company wasn’t interested.”

The Gibb brothers had always been inspired by the R&B of Al Green, James Brown, Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin, but Mardin pointed them toward the orchestrated “Philadelphia Sound” of Gamble and Huff and what was happening in the dance clubs of New York and Miami, where records like the Hues Corporation’s “Rock the Boat” and George McRae’s “Rock Your Baby” were huge. Mardin didn’t just want to tweak their sound, he wanted to overhaul it.

Watch the Bee Gees perform “Jive Talkin'” from Main Course

Another major influence was Derek “Blue” Weaver, the keyboardist brought into the group alongside drummer Dennis Bryon and guitarist Alan Kendall, held over from Mr. Natural. Weaver had been with the successful British group Amen Corner (with Bryon) in the ’60s, and had just left the folk-prog-rock band Strawbs. He was comfortable with synthesizers and conventional keyboards, and had a wide musical knowledge. He knew Maurice might resent losing his traditional spot at the piano, but soon the two achieved a rapprochement, with Maurice concentrating on bass, sometimes matching his overdubs to Blue’s Stevie Wonder-like synth-bass parts.

Criteria was a residential studio. Weaver recalled, in an “oral history of Main Course” compiled by the British journalist Johnny Black, “We all moved into 461 Ocean Blvd. on Golden Beach, and started writing material there. Basically, we’d lie all day on the beach, then work over at the studio in the evening, and late into the night.” Barry later said Dexedrine and liquor were his constant companions as well.

Listen to the hit “Nights on Broadway”

A final, and crucial, change introduced by Mardin was his insistence that the group change its singing style and the tempo of the songs. It wasn’t that he was explicitly aiming to make a dance album, but he wanted more energy than the Bee Gees had shown recently. At one point in the early stages of recording, he asked Barry if he could scream. When he replied he supposed he could, Mardin asked, “OK, but can you scream in tune?” When Barry had some trouble with a particular melody because he had to sing in a low register, the idea came up for him to jump an octave and sing in falsetto. Those were the elements that helped Main Course trigger one of the biggest commercial comebacks in music history.

“Nights on Broadway” opens the album in spectacular fashion. Written by all three brothers, and with the kind of meshed harmonies only siblings can supply, it moves at a good clip after an attention-grabbing start with piano, synth, bass and drums locked. The opening lyrics drag you in: “Here we are, in a room full of strangers/Standing in the dark/When your eyes couldn’t see me.” The middle bridge is a gorgeous ballad-like interlude in the old Bee Gees style. The end groove is where Barry’s falsetto yelps joyously appear for the first time. Released as the second single from the album, it got to #7 on the Billboard Hot 100 list.

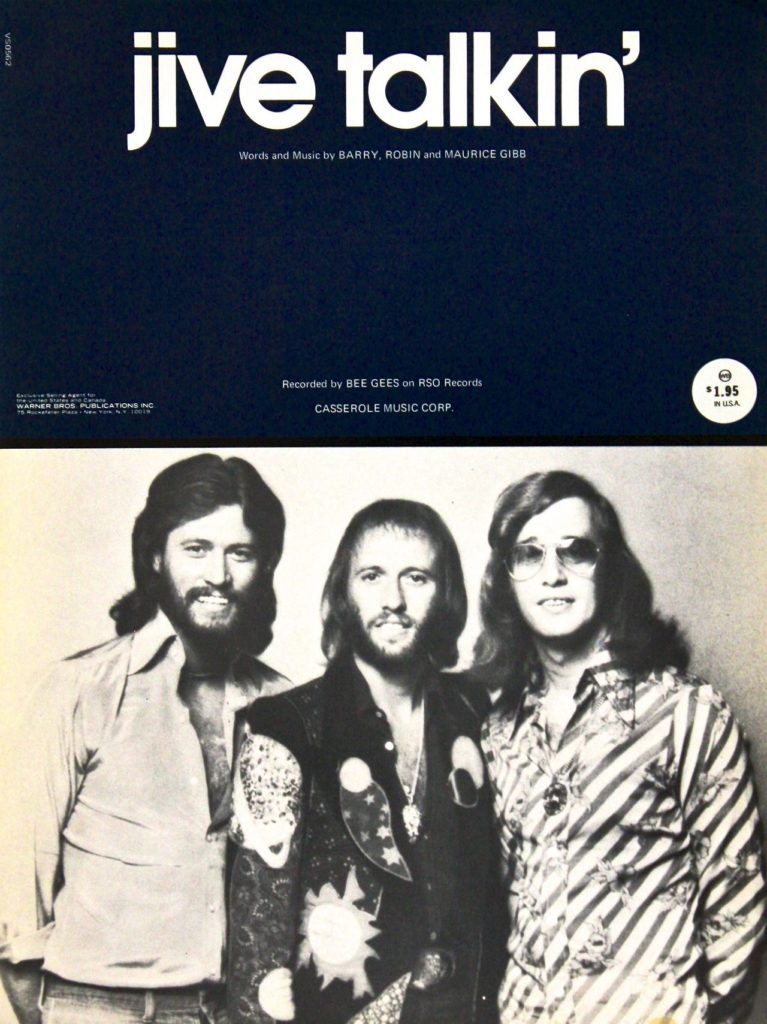

The LP’s first single, which made it to #1, follows. The composing of “Jive Talkin’” began with the sound of the group’s car engine as it crossed a bridge over Biscayne Bay. The bump-bump-bump was infectious. An improvised tune called “Drive Talkin’” became “Jive Talkin’” and underwent further lyrical changes after Mardin explained what Black vernacular “jive talk” was (the Gibbs thought “jive” was a dance). Another Barry, Robin and Maurice co-write, the lyrics might be silly, but there’s no denying the propulsion of the bass lines from Maurice and Weaver, and the latter’s terrific ARP 2600 synthesizer fills.

The LP’s first single, which made it to #1, follows. The composing of “Jive Talkin’” began with the sound of the group’s car engine as it crossed a bridge over Biscayne Bay. The bump-bump-bump was infectious. An improvised tune called “Drive Talkin’” became “Jive Talkin’” and underwent further lyrical changes after Mardin explained what Black vernacular “jive talk” was (the Gibbs thought “jive” was a dance). Another Barry, Robin and Maurice co-write, the lyrics might be silly, but there’s no denying the propulsion of the bass lines from Maurice and Weaver, and the latter’s terrific ARP 2600 synthesizer fills.

“Wind of Change” is next. The versatility of Barry’s voice, from a whisper to a full-throated R&B plea, is on display. Mardin’s arrangement is very Philly, with the basic band supplemented by saxophonist Joe Farrell and percussionist Ray Baretto (overdubbed at Atlantic Studios in New York). For the most part, the Gibb brothers excelled at writing effectively simple love songs, but when the lyrics get more serious, they can be a bit clichéd. “Wind of Change” seems to be spoken by a (Black?) character who wants his story told: “We need a god down here/A man to lead the children/Take us from the valley of fear/Make the lights shine down on us.”

Weaver is credited as co-writer for “Songbird,” a track that has a definite Elton John vibe and even seems to predict the sound Eagles would get when they came into Criteria to record Hotel California the following year. Donny Brooks added a harmonica to the track later in New York City. The lovely “Fanny (Be Tender With My Love)” closes the side. Weaver says his playing on the track was a conscious echo of Hall and Oates’ “She’s Gone,” another Philly-influenced drama on the Atlantic label. Released as Main Course’s third single, “Fanny” reached #12 in Billboard.

It would be fair to say that most reviewers and consumers at the time of release in mid-June 1975 found the second side of Main Course a bit of a let-down after the lively, innovative, hit-single-packed side one. It is still superbly arranged and produced, but it represents the more conventional Bee Gees. And for those who don’t care for Robin Gibb’s vocal waver (often parodied by the anti-Bee Gees faction), his only lead vocals on Main Course are back-to-back, “Country Lanes” and “Come On Over.” The first is orchestrated in the “I Started a Joke” style, and the second is downright country, with steel guitar from Kendall.

“All This Making Love” launches the LP side with a clomping rhythm, some tasty twin guitar figures, and more beautifully blended singing. It perhaps shares some DNA with Todd Rundgren’s “I Saw the Light” and Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Get Down.” “Edge of the Universe” has an excellent vocal arrangement, and with its swooping synth lines resembles what Jeff Lynne was developing with the Electric Light Orchestra around the same time. Listen to the section that begins “I thought that I was going home/And all the way I kept on praying” to hear how Weaver imported some of Strawbs’ prog-rock into the Gibbs’ world.

Related: The Bee Gees’ previous comeback arrived in the form of “Lonely Days”

“Baby As You Turn Away” concludes the album, Barry embracing his full-throated falsetto over acoustic guitars. It’s a mid-tempo beauty with country flourishes and a sweet chorus melody, exquisitely sung. Mardin’s orchestration is understated, and the long fadeout is just right.

The Bee Gees were back. Critics sniped, while begrudgingly admitting it was high-quality stuff that the public loved. Robert Christgau noted the “commercial desperation” that had led to “feigned soulfulness.” Ken Barnes called Main Course “solid, synthetic, ready-made.” Their follow-up album Children of the World contained the hits “You Should Be Dancing,” “Love So Right” and “Boogie Child,” and then Saturday Night Fever happened. Millions couldn’t get enough of whatever the Bee Gees produced, others proclaimed “disco sucks” and made the Gibbs public enemy number one. In the long run, the naysayers lost the argument, because the Bee Gees were just too good at what they did.

Watch the Bee Gees perform “Nights on Broadway” on The Midnight Special

Related: The Bee Gees were the subject of an acclaimed 2020 documentary, How Can You Mend a Broken Heart

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

6 Comments

The best group ever. Robin Maurice we miss you. Barry congratulations on your new endeavor.

Pretty strong comment. There’s quite a few better groups that came before and after them. The Bee Gees were great at what they did but really, they caught the disco wave at just the right time before it came crashing down.

Joe999 doesn’t really seem to know about the Bee Gees.

The Bee Gee’s were and ARE the BEST Pop group EVER! Regardless of the lack of taste or understanding of “some people” who want to equate them with disco. They were never a disco group! Instead, the music they LEAD with, was used for a disco movie and then went on to break records and stay on the charts for 6 MONTHS and sell 40 million! That kind of success shouldn’t even be open for debate! Neither should the fact that they stayed successful, selling out venues for 40 years and making more than 30 albums, when a good average span for most groups was 5 years. I rest my case! I just wish they were all still here for us to say THANK YOU ❤

More than once the Bee Gees surprised the world with their sound. When they first popped into the music scene their first song was sent to DJs without a label. So many thought it was a secret Beatles project. The New York Mining Disaster became a major hit. In 1970 after a two-year breakup they returned with another song unlike their earlier style, “Lonely Days, Lonely Nights”. I find it disingenuous to call them desperate or feigning, they just improvise as artists do.

Fascinating article, in all the details that brought the Bee Gees to their later seventies sound. I do find it incredibly sad that such a great natural group was, essentially, shut down, by everyone they were associated with, for doing what they did, and what so many of us millions loved, for the idea of forcing a more modernized sound that followed trends. Is this what the Beatles would have encountered had they stayed together into the seventies? While there’s no debating the success they found with music they seemingly stumbled on to, being let by their producer and other studio musicians, commercial success and acceptance doesn’t necessarily mean the music was better than what they did naturally. I can handle hearing the Bee Gees later music better now, but I missed “Them” so much in their 70s heyday.