“When Cream died, it died,” drummer Ginger Baker once explained. “Short of murder, we couldn’t solve a problem between us.” Baker and bassist-vocalist Jack Bruce had been fighting with each other, literally throwing punches, drumsticks and chairs, ever since their early-’60s tenure with the Graham Bond Organisation in England. Bond’s group had five superb musicians, but it was like having all passengers in a car insist on having their hands on the steering wheel at the same time.

“When Cream died, it died,” drummer Ginger Baker once explained. “Short of murder, we couldn’t solve a problem between us.” Baker and bassist-vocalist Jack Bruce had been fighting with each other, literally throwing punches, drumsticks and chairs, ever since their early-’60s tenure with the Graham Bond Organisation in England. Bond’s group had five superb musicians, but it was like having all passengers in a car insist on having their hands on the steering wheel at the same time.

When Bond’s addiction to heroin prevented him from effectively managing the band, Baker, no stranger to drug and drink abuse, took it upon himself to fire Bruce without telling his employer. Decades later, having achieved fame as members of Cream with guitarist Eric Clapton, Bruce lived in England and Baker in Africa; Bruce was still wary, telling Rolling Stone’s Jay Bulger, “It’s a knife-edge thing for me and Ginger. Nowadays, we’re happily co-existing on different continents…although I was thinking of asking him to move. He’s still a bit too close.”

Related: Clapton and Winwood paid tribute to Baker following the drummer’s death

When Cream split in 1968, Clapton had no musical plans, but began to visit Steve Winwood at his remote cottage in the Berkshire Downs, when Winwood also was at loose ends after leaving his band Traffic. Clapton wrote in his 2007 autobiography, “When I was having my first doubts about Cream, it used to cross my mind that he was the only person I knew with the musicianship and the power to keep the band together. If the others had shared my interest and let him in, then Cream could have evolved into a quartet, with Steve as the front man, a role for which I lacked not the capability but the confidence.”

Clapton and Winwood would drink, smoke cigarettes, weed and hashish, play their guitars, share song snippets, and talk a lot, with no particular plan. They’d been hanging out together for years, and in fact had already recorded three tunes together as part of “Eric Clapton and the Powerhouse” for Elektra Records’ compilation What’s Shakin’ in 1966, when Winwood was still a teenager and Clapton was in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

One day in early 1969, [the New Musical Express wrote about it on Feb. 8] Ginger Baker arrived at Winwood’s house unannounced, after tearing down the country lanes in his sportscar. “He just showed up with a drum kit and started playing. It was hard to say no,” Winwood later said. At first, Clapton was not pleased. “Steve’s face lit up when he saw Ginger, while my heart sank, because up till that moment we were just having fun, with no agenda,” wrote Clapton in his book. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh no. Whatever’s going to happen now, I know it’s all going to go wrong.’”

With manager/executive producer Robert Stigwood smelling money, the pressure immediately began to record the trio. Clapton was only partly on board, but couldn’t or wouldn’t stop the commercial momentum: “Subliminally, perhaps, my ambition was to re-create The Band in England, an idea that I knew was a huge gamble, which is probably why I named the new band Blind Faith.” For his part, as Winwood told writer Johnny Black, “I knew it was a hype as soon as it was called Blind Faith. I think the name was largely Eric’s idea, but I felt it had certain negative implications. I went along with it only because, after a while, if a band is successful, the name loses its meaning and just becomes a label.” The template for the band was set: if the musicians were in a car, nobody wanted to drive.

First, quick rehearsals were held at Clapton’s new residence Heartwood, then time was booked at London’s Morgan Studios, with Andy Johns engineering. As John McDermott exhaustively documents in the liner notes to the 2001 deluxe CD edition, the trio jammed on blues songs like Sam Meyers’ “Sleeping In the Ground,” worked on “Lord Protector,” a Clapton song that eventually became “Presence of the Lord,” which expressed his joy over finding “a place to live/like I never could before,” and Winwood’s nascent “Had to Cry Today.”

As the sessions continued in March, Baker’s African percussionist buddy Guy Warren (Kofi Ghanaba) fell by for jams on Charlie Segar’s “Key to the Highway” and Bob Dylan’s “One Of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later).” Ex-Moody Blues guitarist Denny Laine came by as well, leading to Baker throwing a fit, screaming at an assistant engineer who’d forgotten to press the “record” button during a particularly tasty jam. Wasting time recording eight instrumental takes of “Hey Joe” didn’t help find a direction either.

Frustrated with the need to play bass parts on the pedals of his Hammond organ, Winwood agitated to bring in a bass player, and Rick Grech, Clapton’s London-based friend from various Speakeasy Club jam sessions, who played with the British blues-prog band Family, was recruited. (Grech didn’t tell his current band he was quitting, so Family leader Roger Chapman was none too happy when Grech simply didn’t turn up for their tour commitments.)

Related: Links for 100s of classic rock tours

A resumption of recording sessions at Olympic Studios on May 27-30 with engineer Keith Harwood yielded 15 takes of Winwood’s “Can’t Find My Way Home,” six of his “Sea of Joy” (with Grech playing violin), and over 50 tries at the never-completed “Time Winds.”

Clapton was trying to mix things up by playing a Fender Telecaster in place of his usual Gibson guitars, but his enthusiasm varied. He resisted efforts to have him sing “Presence of the Lord,” even though it was a very personal song. Stigwood wanted to launch the group pronto, and brought in producer Jimmy Miller to make sense of the stockpile of tape boxes, essentially starting over in June.

Watch Blind Faith perform “Can’t Find My Way Home” live at London’s Hyde Park in July 1969

In a move that staggers the imagination, the half-prepared band agreed to play a free concert in London’s Hyde Park on June 7, 1969. After the opening acts Third Ear Band, Richie Havens, Donovan and the Edgar Broughton Band, Blind Faith came on stage at 5 p.m., facing 120,000 people primed to love whatever was presented from this “supergroup.” Baker, according to Clapton, infuriated him by showing up high on heroin. Baker later snarled, “Eric had been doing amazing stuff, but at Hyde Park I kept wondering when he was going to start playing.” Winwood, who hadn’t encountered Baker in the grip of serious drugs before, saw “how destructive that could be.” Clapton afterward admitted, “I came off stage shaking like a leaf because I felt that, once again, I’d let people down.”

The following week the band played in Helsinki, Oslo, Stockholm, Gothenburg and Copenhagen, returning to finally finish the album with Miller, who’d thrown out much of the “finished” work from previous sessions. On June 23-24 at Olympic they re-did “Had to Cry Today,” with take 17 becoming the master, and completed 13 versions of Ginger Baker’s spotlight number “Do What You Like.” The next day, moving back to Morgan, logs show 24 takes of “Can’t Find My Way Home,” with #21 becoming the master. They were due to start a U.S. tour on July 11, shortly before the album was released on July 21, which happened to be only a few weeks before a little event called the Woodstock Music & Art Fair.

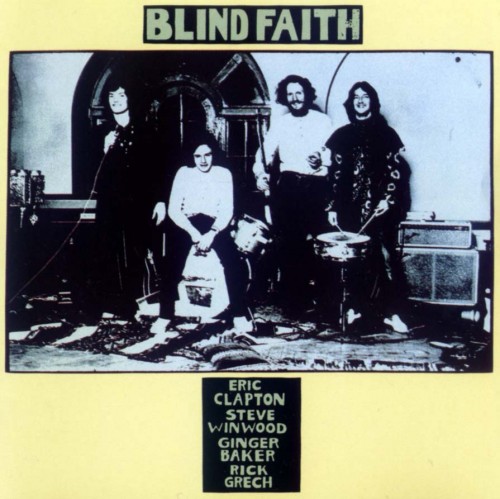

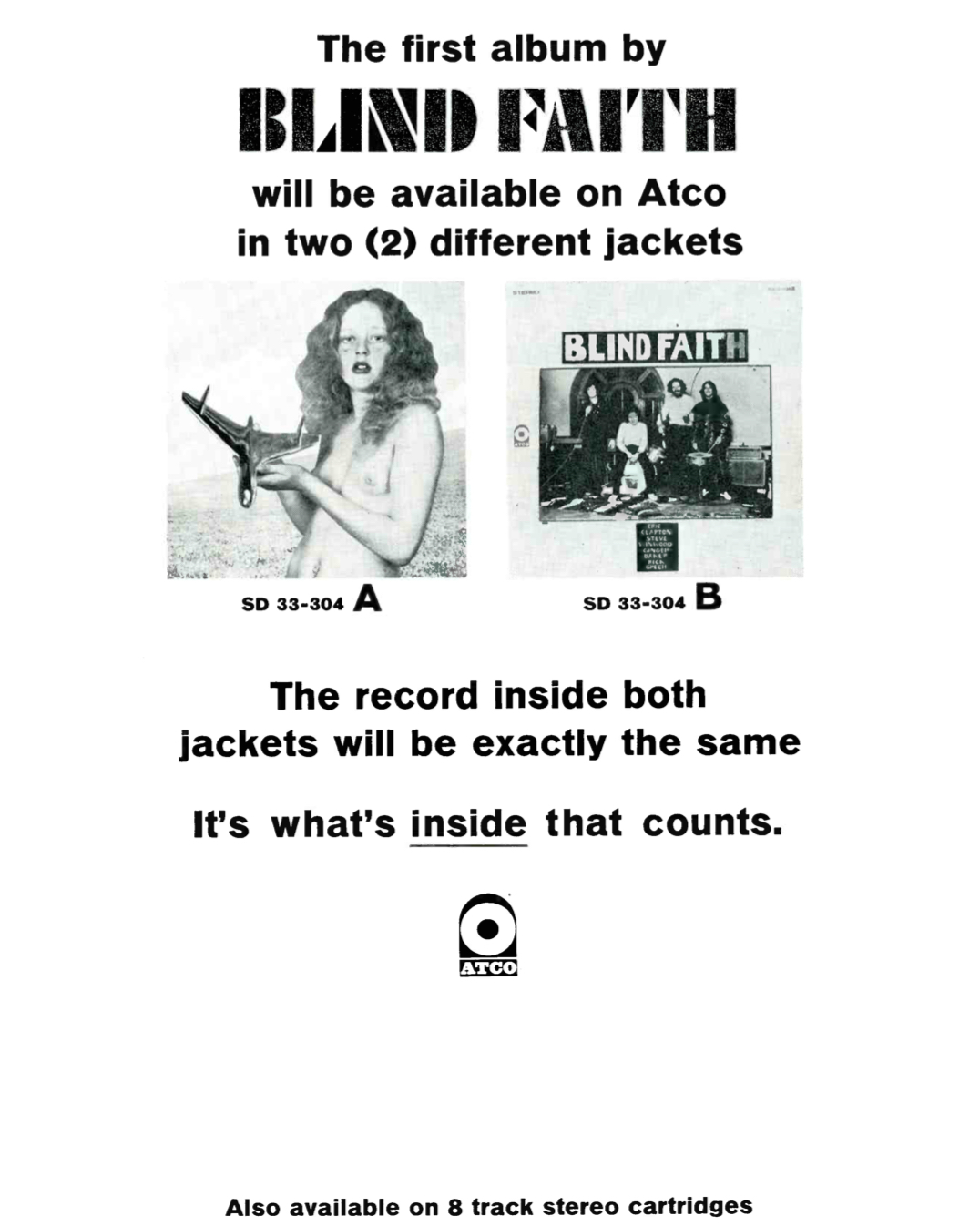

The LP cover, shot by Bob Seidemann, featured a naked pubescent girl with a silver airplane designed by jeweler Micko Milligan, and according to Clapton, “captured the definition of the name of our band really well—the juxtaposition of innocence, in the shape of the girl, and experience, science and the future represented by the airplane.” Their British label Polydor and American label Atlantic’s Atco imprint immediately got huge pushback from retailers who refused to stock the “obscene” artwork, and a hastily designed substitute was rushed out, with a dull black and white photo of the band on a yellow background.

The album was a phenomenon, the tour sold out, and the band disintegrated anyway. From Clapton’s autobiography: “This was entirely my fault and due to one thing. As I became more and more disenchanted with what we were doing, I was falling increasingly under the spell of our support group, Delaney and Bonnie.” Indeed, he joined that band, and used their musicians as the core of his first solo album and the Derek and the Dominos set.

The backstage tribulations didn’t matter when music fans heard the Blind Faith album; it was simply brilliant, and has been considered a classic ever since release. It charted in Billboard for most of the next 12 months, reaching #1. The 15-minute drum feature “Do What You Like” is clearly a sop to Baker, who claimed the copyright, and never stopped complaining about his lack of songwriting royalties from Cream, but the album otherwise contains four spectacular originals and a redesigned vision of Buddy Holly’s “Well All Right” (which was the opening number at Hyde Park). The instrumental arrangements are rich in detail, Winwood sings and plays his butt off, Clapton finds a new, more subtle guitar tone that blends country, R&B and blues, and there is even a Led Zep-worthy riff in “Had to Cry Today.”

Steve Winwood told Black how disillusioned he was by the whole fiasco: “I didn’t want to play coliseums. I was really fed up playing in those places and to those audiences. It was very false. We could play really terrible and get exactly the same reaction as if we’d really played fucking good. When it came down to it, we failed because we couldn’t resist requests for the hits. Ginger did a drum solo and they thought it was Cream, so we chucked in an old Cream song [“Sunshine Of Your Love”]. Then I put in a Traffic song [“Means to An End”] and the identity of the band was killed stone dead. If you have 20,000 people out there and you know you only have to play one song for them to be on their feet, you do it. We were only human.”

Bonus Video: Watch the band perform “Presence of the Lord” live at the Hyde Park concert in London

The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

15 Comments

Yup, I remember when the album was released. I loved it. Didn’t understand any of it, but loved it all the same.

One of the greatest albums of all time! My favorite song is Can’t Find My Way Home. Very sad and plaintive but brilliant at the same time.

Let’s see — an ego-driven, insecure guitar player, whose best work comes as a collaborator, but who can only bear to collaborate with anyone for a limited amount of time. An over-the-top nutjob, with serious hostility issues, and a lifetime heroin addiction, a young musical phenom, who chose to eschew his fantastic lifetime collaborators, in favor of these guys, and lastly, a typically irresponsible bass player, who just blew off his own band and gigs, with no notice, or even communication about leaving, for a seemingly better opportunity. Top it all off with a money-hungry manager, who could care less if the band was ready to do anything or not, relying wholly on the celebrity aspect of the band’s members. Yeah, that has long term success written all over it. I suppose we’re actually fortunate that they were able to put together a minimal-length, classic record. But, seriously, Mark, thanks for these great intricate details about Blind Faith. I’d never heard about any of these things before and found your article fascinating.

Another comprehensive piece by Mr Leviton. When İ interviewed Steve Winwood in the early 80’s he reinforced Mark’s point about feeling that the fans were mesmerized by the idea of a “Supergroup” and as musicians the band felt they weren’t getting genuine feedback on their music – which was indeed superbly captured on the album. Winwood and Clapton in particular felt crowds would applaud anything, and as true musicians, they couldn’t feed off a genuine audience response. İt was disorienting.

Later, of course, many so-called “supergroups” would form and apparently not worry about why the audiences were applauding everything. Perhaps they convinced themselves that everything they did was perfect (lol).

One could also argue that Winwood and Clapton were being overly sensitive, and could have worked through all this. But İ suspect the volatile presence of Baker didn’t help.

Vic, what’s ironic about your comment, and Mark’s original point about Clapton and Winwood feeling dissatisfaction about their audiences’ enthusiasm, not matter what they did, is that for decades not, that appreciation for what he once was is exactly what Clapton has depended and thrived on. He gave up being a musician who made an on-stage effort long ago. Who knows, maybe this kind of adulation had something to do with it, or maybe as his creative energies waned, he began to just coast and rely more and more on that public “Clapton is God” mindset that he once eschewed.

This was the first album I purchased after hearing it a party back in 1969. I wore the album out from playing it so much I had to purchase a second copy. In my opinion this was one of the all time classic albums. Loved every song. Favourite song was Do What You Like with the bass and drum solo.

Talk about opening a can of worms, I found the album excellent, the live concert at hydepark extremely poor, it is what it is !

My alltime favorite album. From the time I was introduced to it, I was hooked. I had often wondered why they had only gotten together to make one album. After reading different articles about the group I learned why.

THIRTEEN versions of “Do What You Like”. That’s a box set all by itself. I gotta say, I put that track right up there with In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida for songs I don’t mind spending nearly 20 minutes with. I’m a sucker for the long version of “Autobahn” and “Tubular Bells” as well.

The true winner on this LP is Paul McCartney, who started buying music copyrights decades before it became the industry it is today. Every time you bought a copy of Blind Faith after the mid-70s, you paid Paul a few cents. He owns Buddy Holly’s publishing.

Ginger Baker is a hoot! He loved to do that double bass drum thing and he loved 5/4 timing “Do what you like”

I saw Cream and Blind Faith live. Still remember Clapton standing about 20 feet on stage in front of us. My girlfriend was an aspiring guitarist, and was mesmerized. Baker was insane on drums. I also saw Hendrix, Joplin and a dozen other people in the next 10 years.

Hey i’m jones-in about the KILLER bands you saw!!!!!!! I have at least 95% of the live stuff out there {many are aud.tapes but I don’t mind!!} on CDR!!A shout out to those tapers !

In May 1970 I obtained a journalism grant in Boston to cover the Manson Family trial in Los Angeles. We camped out at Frank Retz’s property above Spahn Movie Ranch. The remnants of the Family at Spahn Ranch played this album several times a day in the Back Ranch House. It was quite an experience in quite a strange era. The burned to the ground in September 1970. Gone with the wind in the Simi Hills.

Saw them as a 15 y.o. in Copenhagen and must plead guilty to wanting/expecting to hear Cream and Traffic songs and long Clapton solos. It was first after I got the album I realized how brilliant their new songs were.

That’s pretty cool you saw them in Copenhagen way back when but personally, both cream and traffic were much better bands than blind faith . My favorite is the album John barleycorn must die stellar.