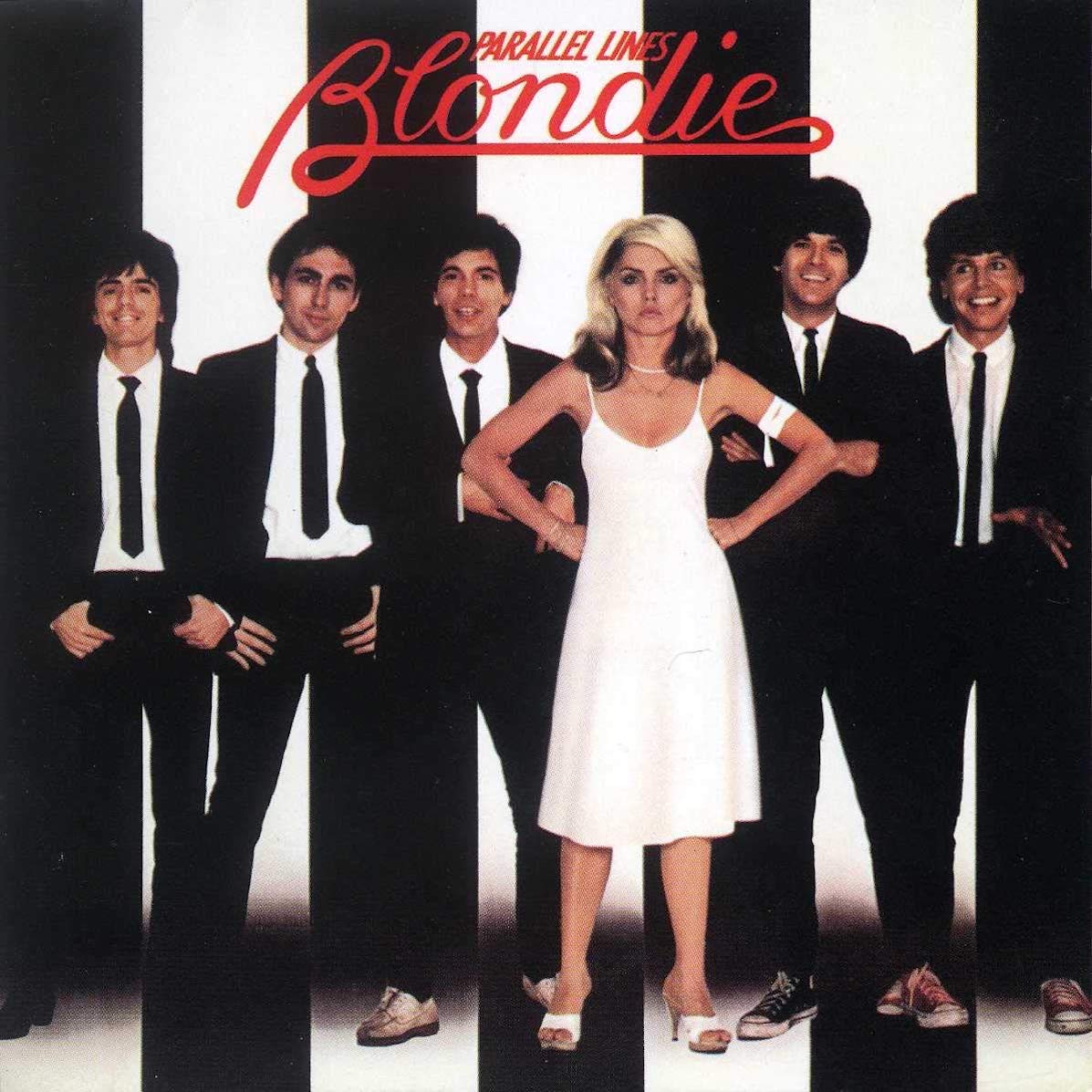

There are countless tales of the great album whose creation begins with the right group of people coming together at an opportune moment to make collaborative magic. On the other hand, successes that launch with a producer determining a band incapable of meeting a professional standard in the studio are comparatively rare. That disarray was a part—and a part of the charm—of Blondie’s Parallel Lines, the 1978 album that would transform the group from boutique act into a worldwide sensation.

There are countless tales of the great album whose creation begins with the right group of people coming together at an opportune moment to make collaborative magic. On the other hand, successes that launch with a producer determining a band incapable of meeting a professional standard in the studio are comparatively rare. That disarray was a part—and a part of the charm—of Blondie’s Parallel Lines, the 1978 album that would transform the group from boutique act into a worldwide sensation.

In the seven months following the release of Plastic Letters, everything changed for the six-person New York band. Its second album was making little headway in the U.S., though its single “Denis” (a remake of Randy and the Rainbows’ 1963 “Denise”) performed well in Europe, reaching as high as #2 in the U.K. Stateside, the band achieved scant notice outside of punk/new wave circles, which led band manager Peter Leeds to suggest a change. Impressed by Australian producer Mike Chapman, Leeds brought him in to replace Richard Gottehrer, the writer/producer who had worked with the group on its first two records.

Watch Blondie perform “Denis” live in 1978

Mixed emotions about the change, including initial reticence on the part of vocalist Debbie Harry, were overcome, and Chapman joined the band for sessions at New York’s Record Plant in June 1978. Committed to technical proficiency in ways Gottehrer was not, Chapman found the group at the outset of rehearsals to be a poor match for his method. For all the frenetic energy they brought to the table, drummer Clem Burke and keyboard player Jimmy Destri were imprecise musicians who had difficulty delivering consistent performances, and guitarist Chris Stein frequently showed up to sessions under the influence. In a 2008 interview with Sound on Sound, Chapman summed up his initial experience with the band as, “They just wanted to have fun and didn’t want to work too hard getting it.”

Chapman focused on sharpening his players’ chops, and at the same time learned how to manage the mercurial Harry, with a focus on adding texture to her approach. By all accounts, the relationship was a rocky, push-and-pull affair from its outset, but the six-week recording process yielded undeniable results.

Related: 10 songs that defined new wave music

Although Chapman was intent on delivering a hit record, its commercial prospects did not rear their heads when the initial single appeared in the U.S. The Buddy Holly cover “I’m Gonna Love You Too” hits the ear like an unholy mating of ’60s girl group music and punk in a song that writhes, pulsates and jabs all the way through. It is a notable showcase for Harry’s versatility, as she cross-pollinates brassy insistence and purring nuance in ways that far outstrip the limited sonic variety in which she’s nestled. It was not a sound for which radio was yet ready, and failed to chart.

Watch Blondie’s cover of Buddy Holly’s “I’m Gonna Love You Too”

The lead single in the U.K. made a somewhat more traditional use of its throwback sensibilities, ratcheting them into “Picture This.” A quirky love song with a chorus exhumed from the doo-wop era and splashes of pure new wave in Stein’s electric guitar fill, its loping sway assembles many familiar pieces into something modern and restless, right down to its amusing (and prescient) lyric promising to, “get a pocket computer try to do what you used to do.”

Instinctive energy coalescing around craft is foundational for Parallel Lines, where wildness is embraced rather than erased, and forged smartly from threads of multiple stylistic ideas into digestible pop. The album’s first track, “Hanging on the Telephone,” is a clinic on how to shape bombast without neutering it. Following a lead-in of long-distance rings, Harry leaps in half a measure before the remainder of the band, her echo-trimmed vocal a sharp jab that kicks open the door for a frenetic swirl and blistering double backbeat. Chittering synthesizer snakes left to right and back again, helping open up a panorama of lively atmosphere. Smartly decorated yet still raw, it’s a remarkable balancing act.

Harry later recalled, “Hanging on the Telephone” was a song by The Nerves, a band from LA that Jeffrey Lee Pierce had sent us a cassette of. We played it in the back of a cab in Tokyo and the driver, who didn’t speak English, started tapping the steering wheel. Chris and I looked at each other and thought, ‘OK this guy is going with it and he hasn’t got a clue what it’s about, he’s just responding to the song, which we took as a sign that we had to do it.’ We made a version like a Shangri-Las song with a sound effect, a British telephone ringtone.

Its title taken from a song never finished for the record (but whose lyrics appeared on the liner notes of early pressings), Parallel Lines is a collection of singular ubiquities, songs of unique character and enormous staying power. There’s “Fade Away and Radiate,” a spacey, oddball number framed around obsession with long-dead film stars. It is artful and contemplative, cool and ethereal, with a bit of rock grit to dress it up, and guitar work from Robert Fripp to enhance its quirks. The sum is a heady pop song no other band could create, meshing obscure imagery with flavorful musical tropes.

[Sources note the album was released September 23, 1978, but that is the day it debuted on the U.S. sales charts.]

Its lasting moments yielded hits among the most offbeat of their generation. Carrying stalker vibes that put the Police’s “Every Breath You Take” to shame, “One Way or Another” is at once a genuinely dark and irresistibly juicy mash of pop and rock. Loose and rangy, it is also professional and precise, from Harry’s nasty vocal whine to Burke’s insistent-and-then-some drum patterns, which drive atmosphere in a herky-jerky stop/start romp. The album’s fourth and final U.S. single, it reached number 24 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Listen to “One Way or Another”

While it was not precisely deconstructive, the group clearly favored atypical cross-pollinations. “Pretty Baby” is a house blend of throwback ’60s flavor in the refrain and modern ideas all around it, turning expectations of both reams on their respective ears. With its driving, frenetic pace, “Will Anything Happen?” flashes punk-leaning energy, but as Harry surfs atop a spray of rattling cymbals, guitar chug and Destri’s thickly slathered keys, it’s very much under control. The tropes of primal agitation are there, but instead of rebellion, it offers wit. The singer is similarly at ease among the frantic in “11:59,” alloying driving punk inflections to old-school pop and new wave attitude. Puzzle pieces assemble in ways that seem unlikely to fit, yet interlock to create vivid, smartly decorated canvases.

Harry‘s adaptability is essential to the success of Blondie’s patchworks. Her nearly affect-free vocal moors “I Know But I Don’t Know” with hypnotic personality that brings focus to its taut throb. On “Just Go Away” her sound ranges from pretty to snippy, augmenting its spunky bounce with attitude to spare. For “Sunday Girl,” which would top the charts in the U.K., she delivers affect and color, feeling her way around its chunky throb of guitar and bass. The group’s avant-garde leanings require a vocal chameleon, and Harry changes shade with the best of them.

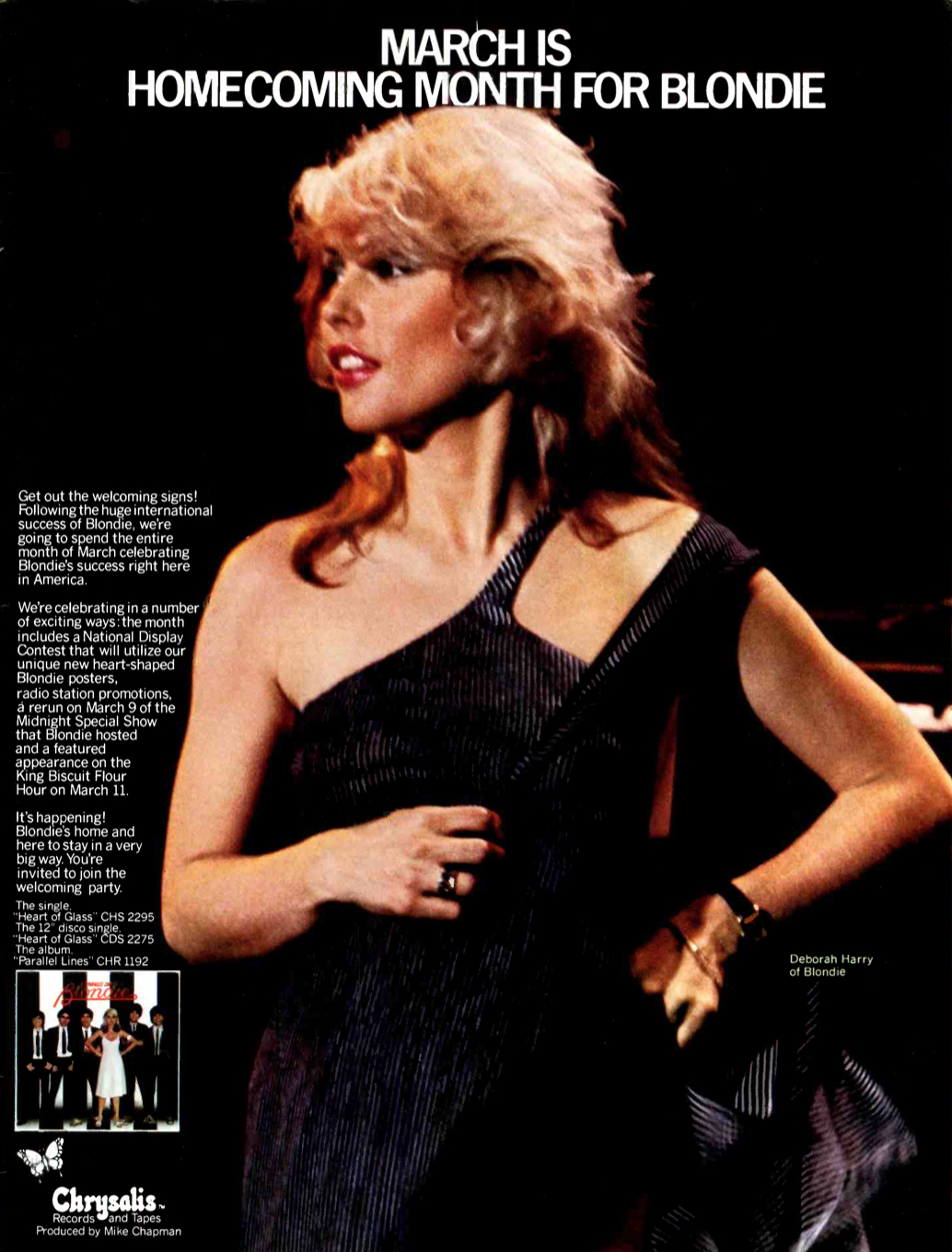

Amid its singularities, the one that most defined the record was “Heart of Glass.” Built from a Harry/Stein track the band had unsuccessfully tried to complete for years, its final form as a disco number with European flavor proved inspired, and spawned an enormous international hit. Rich with fluttering atmosphere and color, from its dynamic keyboards to a mix of Burke’s live drums and a program on the then-new Roland CR-78 drum machine, the song feels at once experimental and utterly commercial.

Burke initially disliked the result and resisted the idea of playing it live; that has not worked out quite as he planned. Despite some initial radio headwinds toward a lyric that referred to a past love as “a pain in the ass,” the song topped the singles chart in several countries, among them the U.S. and U.K., and sold more than a million copies in each of the two. Its original version was replaced with a 5:50 disco cut on album pressings beginning in March 1979 (one month before the song was certified platinum), though the original would later return for the album’s initial U.S. CD release in 1985.

Propelled by its hits, Parallel Lines became an international smash, and rocketed Blondie to a new level of success. It peaked at #6 in the U.S. and would go on to sell a reported 20 million copies worldwide. It also marked the beginning of a successful partnership for Chapman and the band—he would produce the group’s next three records, plus the lion’s share of Harry’s solo project Def, Dumb and Blonde in 1989. It was an ideal confluence—the right people in the right place at the right time.

Watch the video for the smash single “Heart of Glass”

Bonus video: Listen to “The Disco Song,” an early arrangement of what would later become “Heart of Glass”

When Blondie tour, tickets are available here and here.