Dylanologists are completely justified in hailing Blonde on Blonde as Bob Dylan’s first major masterwork and a turning point in his trajectory, from a tousle-haired folkie with a penchant for protest to a committed rock and roll rebel, whose sarcasm, sneer and cynicism made him an auspicious auteur possessing both edge and audacity. Recorded in Nashville, it paved the way for his eventual turn to country music with Nashville Skyline some three years later, bringing him into a new musical circle that once seemed oblivious to this New York upstart, but quickly found a way to underscore his efforts. It boasted some of his most adventurous work up to that point, whether it was the ragtag refrains of “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” and “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat,” the lovelorn plea of “I Want You,” the tossed-off dejection of “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine,” the pining balladry of “Just Like a Woman,” the dream-like “Visions of Johanna,” or simply the ache and anguish shared so eloquently in “Sad Eye Lady of the Lowlands” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again.”

Dylanologists are completely justified in hailing Blonde on Blonde as Bob Dylan’s first major masterwork and a turning point in his trajectory, from a tousle-haired folkie with a penchant for protest to a committed rock and roll rebel, whose sarcasm, sneer and cynicism made him an auspicious auteur possessing both edge and audacity. Recorded in Nashville, it paved the way for his eventual turn to country music with Nashville Skyline some three years later, bringing him into a new musical circle that once seemed oblivious to this New York upstart, but quickly found a way to underscore his efforts. It boasted some of his most adventurous work up to that point, whether it was the ragtag refrains of “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” and “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat,” the lovelorn plea of “I Want You,” the tossed-off dejection of “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine,” the pining balladry of “Just Like a Woman,” the dream-like “Visions of Johanna,” or simply the ache and anguish shared so eloquently in “Sad Eye Lady of the Lowlands” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again.”

Draped in a profound poetic haze, Blonde on Blonde reinforces the notion of Dylan as an abstract poet, with descriptive song titles that reaffirmed the vagueness inherent in his hazy sense of romance and resolve. “Temporary Like Achilles,” “Rainy Day Women,” “Obviously 5 Believers” and “4th Time Around” seemed to toe a line between free association and fanciful finesse, leaving it to the listener to decipher the meanings all on their own. Even the album title has become the subject of conjecture; while the initials spell out Dylan’s first name—and also riff on Brecht on Brecht, a stage production based on the work of German playwright and Dylan’s early inspiration, Bertolt Brecht—Dylan himself has said he doesn’t recall how the name came about.

Indeed, as it often transpired at various points throughout Dylan’s careening career, myth and music are inextricably intertwined.

In essence, the album came about somewhat haphazardly. Dylan had initially begun recording in New York, but soon became dissatisfied with the results. Of all the material attempted, only the song “One of Us Must Know (Sooner of Later)” was deemed acceptable for inclusion. When producer Bob Johnston suggested shifting the location to Nashville, an unlikely setting given that the divide between rock and country music had yet to be breached, Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman objected. Nevertheless, Dylan agreed to give it a try, and with erstwhile sidemen, keyboardist Al Kooper and Hawks (later the Band) guitarist Robbie Robertson in tow, they reconvened in Columbia’s Studio A on Music Row, where an A-list of the city’s finest studio musicians—guitarist, bassist and harmonica player Charlie McCoy, guitarist Wayne Moss, guitarist and bassist Joe South and drummer Kenny Buttrey—awaited instruction.

McCoy, who had previously worked with Dylan on Highway 61 Revisited, and was then recruited for Blonde on Blonde and the two albums that followed, John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline, recalls that Dylan was remarkably withdrawn and more preoccupied with completing his lyrics than taking an active part in the arrangements. At one point, when he asked Dylan how a certain song should sound, Dylan replied by telling him that whatever McCoy and the others were willing to go with was fine with him as well.

“That’s about all he said during the four albums we did together, even when we were face to face,” McCoy recalls. “I heard someone once say he didn’t have an answer for hello.”

Nevertheless, the music that defined each song is as solid and sturdy as anything in the Dylan canon. The loping revelry of “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” was a stoner’s delight, its shouted-out chorus enticing one and all to imbibe, get high and opt for carefree abandon. It’s said that Dylan originally wanted to take the track’s title from that prophetic line in the catchy chorus “Everybody must get stoned,” but abandoned the idea because he realized it would limit the airplay possibilities.

Nevertheless, the music that defined each song is as solid and sturdy as anything in the Dylan canon. The loping revelry of “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” was a stoner’s delight, its shouted-out chorus enticing one and all to imbibe, get high and opt for carefree abandon. It’s said that Dylan originally wanted to take the track’s title from that prophetic line in the catchy chorus “Everybody must get stoned,” but abandoned the idea because he realized it would limit the airplay possibilities.

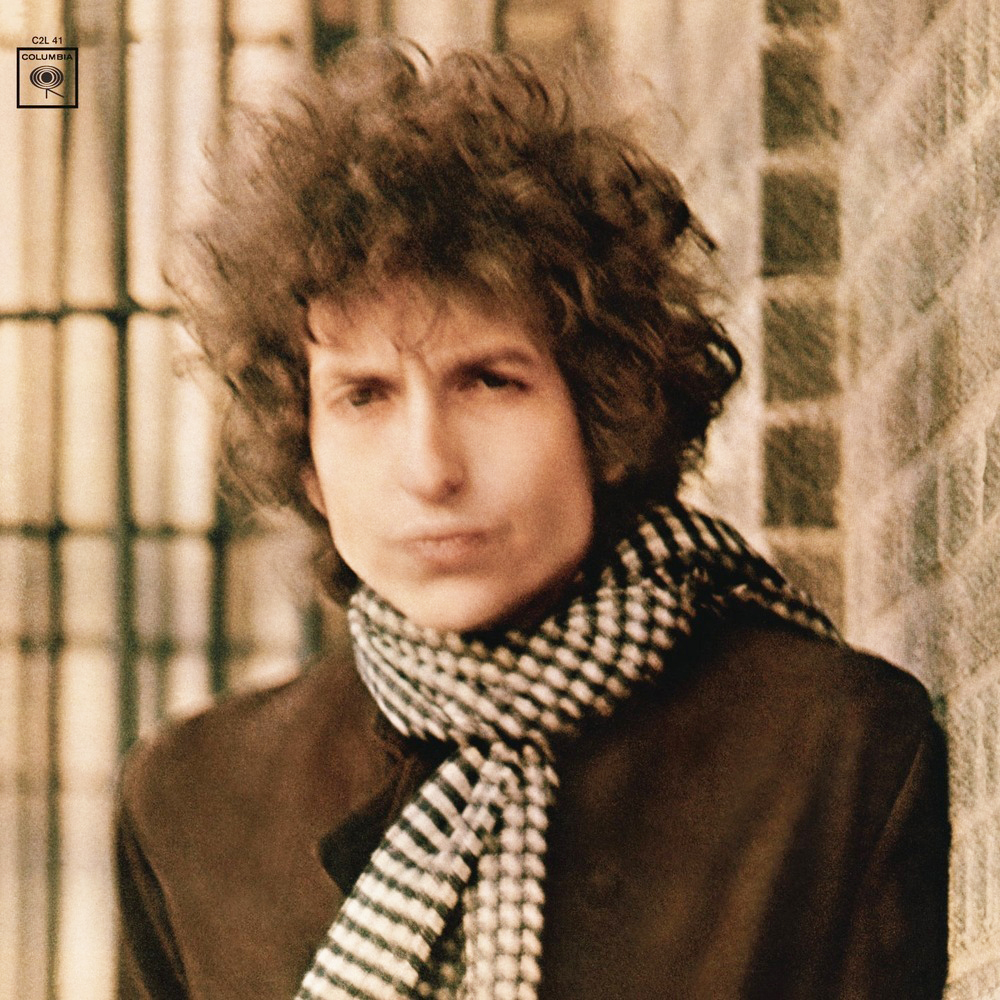

At this point in his career, Dylan clearly seemed preoccupied with his irascible attitude, as the scowl he bore on the album cover appeared to attest. “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later),” “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine,” “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” and Temporarily Like Achilles” are thinly veiled, bitter diatribes targeted at the lovers that spurned him, an act that Dylan typically cast as an absolute betrayal. “Positively 4th Street” is an early example.

That said, Blonde on Blonde also boasts two of the Bard’s most stunning love songs. However, even in that context, there’s no small hint of underlying animosity. “Just Like a Woman,” with Kooper’s signature organ intro, focuses on sympathy and suggestion (“She aches just like a woman/but she breaks just like a little girl”) or simply as another rebuke (“Everybody knows that baby’s got new clothes/But lately I see her ribbons and her bows/Have fallen from her curls”). The culmination that comes through the song’s crescendo suggests that Dylan’s taking an assertive stance, but it’s hardly the kind of uplifting anthem most feminists would hope for.

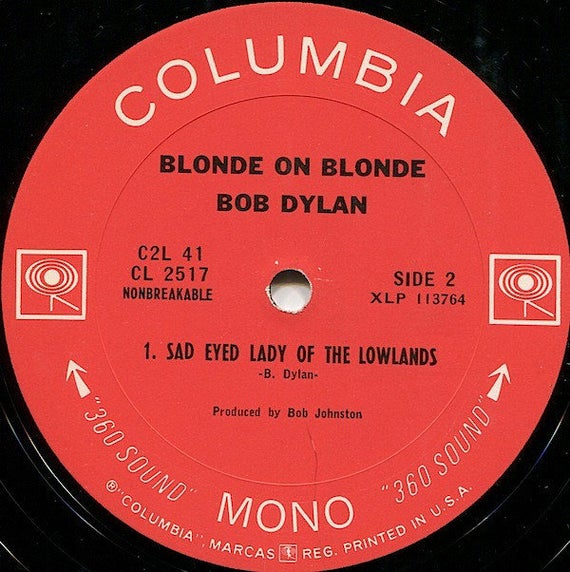

On the other hand, “I Want You” offers no doubt about Dylan’s depth of desire, and when he declares “I want you so bad, oh honey, I want you,” his intention is obvious. It’s a clear contrast to the idealized heroines he sings of in “Visions of Johanna” and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” each song a spiritual soliloquy of sorts that finds mythological women placed on pedestals, imagined in a kind of dream-like ambiguity. Like Leonard Cohen and his “Suzanne,” Dylan was smitten by his melancholy muse.

Related: Dylan is still the colossus

When it was released in late June 1966 as a double album—a rarity at the time and an obstacle to overcome as far as cost to the consumer was concerned—Blonde on Blonde debuted on the U.S. album chart on July 16. It ultimately reached the top 10 in the U.S. and the top 5 in the U.K. Rightly considered a classic, it is, in many ways, still Dylan’s defining album, one that helped to affirm his lingering largess. Now, more than 55 years after its initial release, its iconic standing remains as indelible as ever.

Bonus Video: Watch Dylan perform “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” live at Farm Aid in 1986

Bonus Video 2: Watch Dylan perform “Just Like a Woman” with Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers in 1986

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

2 Comments

Great review. Only one nit. IMO his first masterwork was Highway 61 Revisited.

Oh yes, Highway 61 was a masterpiece. I think an earlier great one was Freewheelin’.