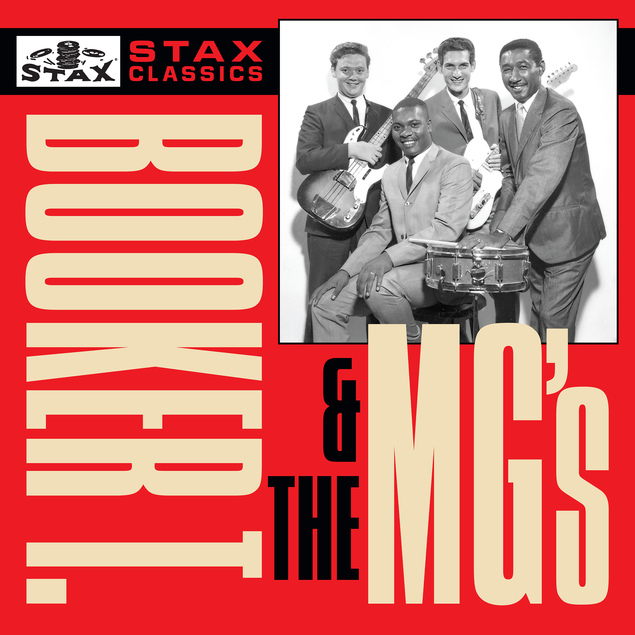

There never was any doubt who would be the first all-instrumental band inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: That honor had to—and did, in 1992—go to Booker T. and the MG’s, the Memphis-based quartet featuring Booker T. Jones on organ, Steve Cropper on guitar, Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass and Al Jackson Jr. playing the drums.

There never was any doubt who would be the first all-instrumental band inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: That honor had to—and did, in 1992—go to Booker T. and the MG’s, the Memphis-based quartet featuring Booker T. Jones on organ, Steve Cropper on guitar, Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass and Al Jackson Jr. playing the drums.

They first came to our attention as an entity in 1962 with their #3 hit “Green Onions,” a song that quickly found its way into the repertoire of countless garage bands, and continued to record hits for the Stax label through the remainder of that decade, including two further top 10 singles, “Hang ’em High” (1968) and “Time is Tight” (1969).

But Booker T. and the MG’s did a lot more than record under their own name. As the house band at Stax (MG’s stood for Memphis Group), they played on hundreds of recordings by other artists, including Sam and Dave, Otis Redding, Carla Thomas and Albert King. They also served often as the backing band for their labelmates onstage. At the fabled Monterey Pop Festival of 1967, the MG’s played not only their own set but provided the dynamic accompaniment for one of the festival’s true stars, Otis Redding.

The MG’s split in 1971, then reunited a couple of times, while Jones branched out into a solo career that included production work for Willie Nelson and others. Two members of the MG’s, Jackson and Dunn, are no longer with us, but the quartet continues to inspire—just ask the Blues Brothers, Neil Young and so many others.

Watch Booker T. and the MG’s perform “Green Onions” live

Booker T. Jones was born November 12, 1944. We spoke with him on two occasions, in 2011 and 2013. Most of those two conversations has never been published before.

Best Classic Bands: Who were some of the Hammond organ players that influenced you when you were starting out?

Booker T. Jones: Ray Charles! He moonlighted on the Hammond M3 organ on a song called “One Mint Julep” that Quincy Jones arranged. I heard that and it struck me. I knew that I would like to make that sound; that’s what I was striving for. Then I heard Bill Doggett and Jimmy Smith and Brother Jack McDuff down on Beale Street in Memphis.

What drew you to R&B rather than jazz?

There were a lot of great jazz players that came from Memphis—Joe Dukes, Booker Little, Hank Crawford. It was a lifestyle. I was also into gospel music and classical music. I studied classical music with my mother and my piano teacher, Mrs. Cole. My first lessons were Bach and Beethoven and that music is still in my system. I studied classical and conducting and it’s a completely different lifestyle. I talked to [jazz bassist] Stanley Clarke and he said you have to live their life.

Why do you think Memphis produced so many great musicians during the time you were coming up?

That’s a great question. I’m just glad I was born there rather than, say, St. Louis. I don’t know what it was. All the great writers were born in Athens, Greece. There are centers of energy on the Earth and certain people gravitate there. Look at what happened in San Francisco.

Going back to the beginning of the MG’s, did you take a lot of flak for having an integrated band in the South in the early ’60s?

The South didn’t know about us; we wouldn’t have existed if they had known what was going on. We were sequestered there on McLemore Avenue in the [Stax] studio. The world didn’t know until they heard the records, and even then they segregated us. The black people thought it was a black band and the white people thought it was a white band. We’d play either white clubs or black clubs. It was either/or. I didn’t get any flak internally [at Stax] about having an integrated band. Nobody cared. There were some extremists on the outside who cared. I actually took more flak for leaving Stax in 1962 and going to Indiana University.

Why did you decide to go back to school just when the group was starting to hit?

I was in 12th grade when we recorded “Green Onions” and that was a great song but I didn’t really know what I was doing. I couldn’t sit down and write what I was hearing in my head. I couldn’t write the string parts. So I paid my tuition when we cut the record and went through with the whole thing. And I’m glad I did.

What did you learn there?

Oh, my God, I can’t possibly begin to tell you how my horizons were expanded. I took four years of music theory at 7:30 in the morning. That will give you confidence. I was used to playing at jam sessions in New Orleans till 3 a.m.

How did you apply what you learned to your songwriting later on?

It changed the course of it. It changed the course of the way I did melodies. Sitting there and studying melodies from all parts of the world made me a better songwriter.

Did you know when you cut “Green Onions” that you had a hit on your hands?

Absolutely not. It was just a little ditty that I’d done in the clubs. I was supposed to play it on the piano but I happened to play it on Hammond organ. It was just a fun song to play and I loved the sound of it but I was so surprised to hear it on the radio.

Related: “Green Onions” is one of our picks for the 10 great instrumental hits of the ’60s

Who was your favorite Stax artist to back up?

That’s a hard, hard question. They were all great. I have to put Otis Redding at the top but I wouldn’t say he’s my favorite. I would say that he was the most dynamic, probably. But we loved Albert King, Sam and Dave, Carla Thomas, Eddie Floyd.

Do you have a favorite studio session that you played on?

“(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay” with Otis, which I played piano on, was pretty special. We never did all-nighters but this time he insisted—maybe he had some kind of premonition—that we stay and not go home. We recorded that song during that time. I didn’t know it would be a hit but we loved the song.

What was the dynamic like between the Stax artists?

There was a battle going on once we hit the stage; we became different people. Otis Redding was the king of Stax in that he carried the banner. He led us in a lot of different ways. He almost led us to rock music. Sam and Dave were huge for us. Isaac Hayes became huge for us. He was a nobody when he walked in. He was trying to imitate Nat King Cole.

Did you feel more of a responsibility than the other MG’s because the band was named after you?

I was responsible for bringing the music to the table. When we went to have a session, they didn’t treat us like the other artists. We were always backing people up there. So when we had a spare day they would say, “OK, let’s record a song for Booker T. and the MG’s.” I had to have something new and original. But it gave me a legacy and a place in life.

Watch Booker T. and the MG’s perform “Time is Tight”

The MG’s had a very clean, undistorted sound, which was unusual for the psychedelic era. How did you come up with that?

That was a conscious effort. We all had an understanding that we would keep it simple and funky. We would monitor each other to not play too much and not get too outrageous. We wanted to keep it accessible. Al Jackson was the guardian of that more than anybody else. Duck Dunn was his partner—I would try to lead them in different directions and they would reel me in. It was a friendly push and pull. When we did the Melting Pot album, that was me pulling the whole band in a completely different direction. But the tension worked.

What are your memories of the Monterey Pop Festival?

That was a mind-opening thing. We had just gotten back from Europe and it was a different experience for me, a beautiful experience. When we got to the gig the Hells Angels escorted us in. The only time I had been away from Memphis was to Europe for the ’67 tour. I was so impressed by Monterey that I moved to California. That city was transformed for that pop festival. If you didn’t have money for food you didn’t have to pay. Somehow they got the police off the streets. People were sharing rooms at hotels. It was different. They accepted us wholeheartedly that night at the concert.

Had you heard of some of the new artists on the bill, like Jimi Hendrix?

I’d heard of him but I didn’t know what his thing was.

What did you think of the reaction that Otis Redding got from that crowd?

He was blown away by it. He was nervous and apprehensive and didn’t know but they made him feel comfortable from the first minute. It changed my life in a lot of ways.

Watch Otis Redding perform “Try a Little Tenderness” at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, backed by Booker T. and the MG’s

The MG’s cut an album of Beatles covers called McLemore Avenue. Why did you decide to do that album?

Because of what they were doing. They were doing earth-shaking, groundbreaking things, a four-piece band from England moving at lightning speed. They were different from everybody and making music that was timeless. I wanted to pay tribute to it.

What did you learn about production at Stax that you used later on when you started producing records?

With Willie Nelson’s Stardust [1978] it was similar to a Stax production, but I couldn’t have produced Willie at Stax. That would have been absurd. But the record that we did was very much like a Stax record in that it was sparse and clean and easy to understand and easy to listen to. It was the same with Bill Withers. [Jones produced the singer’s Just As I Am in 1971.] But with people like that, you have to have the material first. Bill was an extraordinary songwriter because he’s an extraordinary person and he understood society and the songs he wrote were so easy to relate to. He wrote “Lean On me,” for God’s sake.

How did your collaboration with Willie come about?

That was the kind of serendipity that I’m involved in; things happen in my life. I looked down from my deck one day in my apartment in Malibu and this guy was on the beach with his red hair and that was Willie Nelson. He rented an apartment right underneath me. So we ended up jamming on his deck and my deck and we had all these tunes in common that we loved and were playing all the time. It was his decision to go into the studio and record them.

Listen to the title track from Willie Nelson’s Stardust, produced by Booker T. Jones

Stardust took Willie out of country. He’d never done anything like that before.

I would say it brought country to him. I think it really expanded country. It sold so many copies.

You also collaborated with Neil Young. He was on your Potato Hole album in 2009 and the MG’s did a tour backing him.

I met Neil in New York [in 1992] playing a tribute to Bob Dylan. We had a whole week of rehearsal and I was in the backup band. A lot of the rehearsals turned into jam sessions and Neil’s was one of those. I don’t know how many songs we rehearsed but we ended up playing one song on the show. But we hit it off.

Watch Neil Young perform “All Along the Watchtower,” backed by Booker T. and the MG’s

That led to the first new MG’s album in 17 years, That’s the Way It Should Be [1994]. What was the reunion like for you?

That was good. The reunion was without Al Jackson Jr. Al was a huge force, not only in the MG’s but anything he touched. But the other elements of it were really great.

What’s next for you?

I’m riding this wave and not planning anything. Things are falling in my lap and I’m enjoying it.

Watch Booker T. Jones perform a solo NPR Tiny Desk Concert

Booker T & the MG’s were among those selected for induction into the Blues Hall of Fame’s Class of 2019, the institution’s 40th induction class. Booker T continues to tour; when he does, tickets are available here.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024