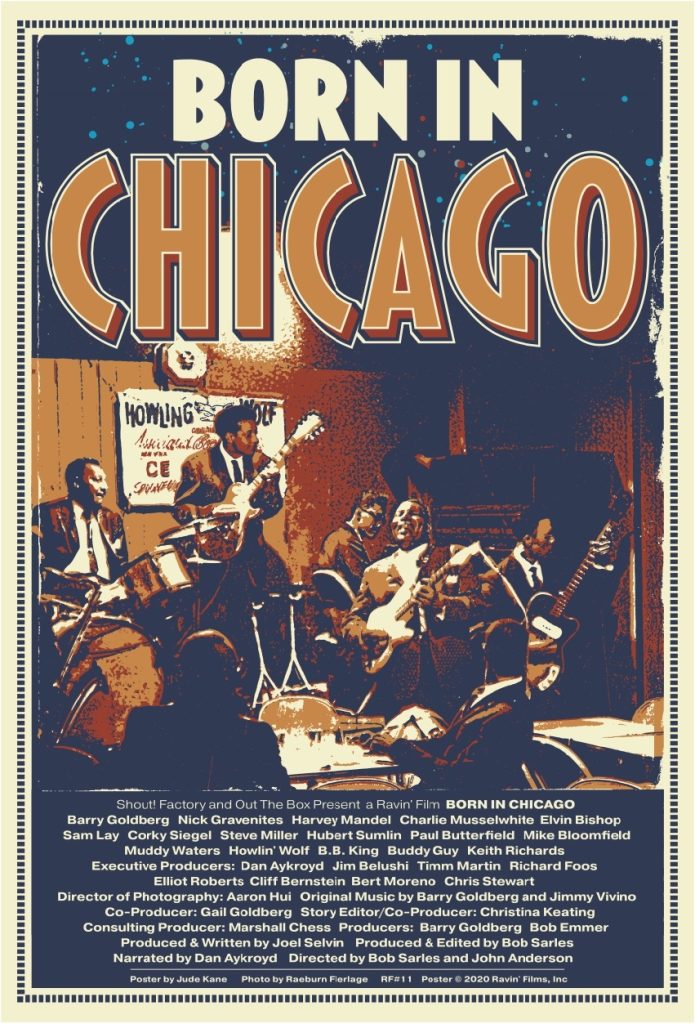

A new music documentary on the rich history of the Chicago blues scene, Born in Chicago, will be available on all major digital platforms on August 1, 2023. Born in Chicago, a Ravin’ Film, was written by respected music historian Joel Selvin. The film includes archival footage alongside interviews with Keith Richards, Bob Dylan, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Steve Miller, Harvey Mandel, Charlie Musselwhite, Barry Goldberg, Hubert Sumlin, Corky Seigel and many others.

A new music documentary on the rich history of the Chicago blues scene, Born in Chicago, will be available on all major digital platforms on August 1, 2023. Born in Chicago, a Ravin’ Film, was written by respected music historian Joel Selvin. The film includes archival footage alongside interviews with Keith Richards, Bob Dylan, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Steve Miller, Harvey Mandel, Charlie Musselwhite, Barry Goldberg, Hubert Sumlin, Corky Seigel and many others.

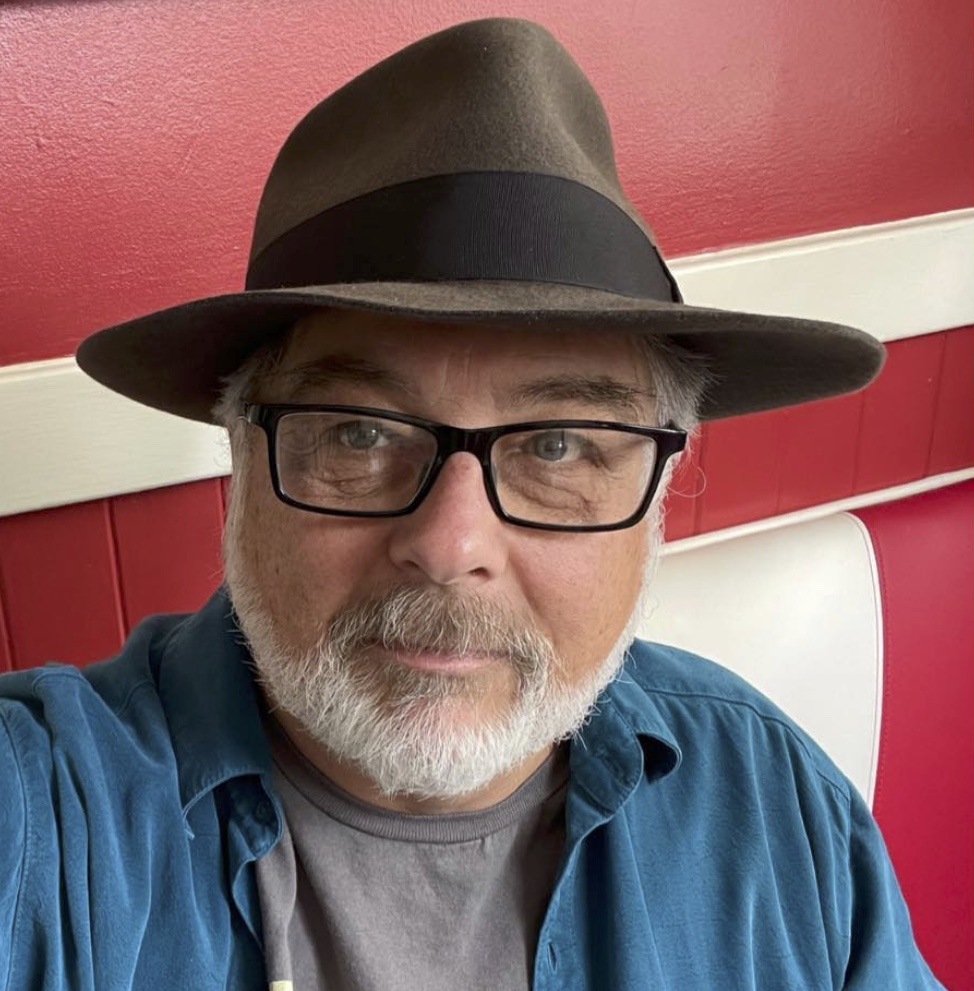

Born in Chicago was co-directed by Bob Sarles (BANG! The Bert Berns Story, Sweet Blues: A Film About Mike Bloomfield) and John Anderson (Horn From the Heart: The Paul Butterfield Story, Brian Wilson Presents Smile). Best Classic Bands spoke with Sarles about the making of the film and the importance of Chicago blues.

The film is narrated by Dan Aykroyd and Executive Produced by Jim Belushi and Elliot Roberts. Original music for the film was composed by Jimmy Vivino and Barry Goldberg.

From the press release announcing the film: “In the late 1950s the dynamic Chicago blues scene was at a crossroads. The music’s patriarchs—Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf—were still vital and playing regularly at the many blues clubs on the city’s South Side. But the scene had peaked, as young African-Americans were discovering the sounds of Motown, Stax and the soul of James Brown. The new generation saw the blues of their parents and grandparents as antiquated, a remnant of an era best left to the past. At the same time white adolescents in the suburbs of Chicago and other cities were listening to black radio stations late at night and were just discovering this mysterious and forbidden music.

“In the early ’60s young white musicians from Chicago’s suburbs began to venture to Chicago’s South Side to see in person the music they had been hearing on the radio. Soon, these musicians, among them Mike Bloomfield, Barry Goldberg and Harvey Mandel, befriended their musical heroes and soon became accepted among the musicians playing at Chicago’s Black blues clubs. Born in Chicago tells this fascinating story through the voices of those who were there and extensive use of rarely seen archival footage.”

Best Classic Bands: What attracted you to the subject of Chicago blues and its influence?

Bob Sarles: I had previously made a documentary about Mike Bloomfield. I had been a fan of his, and had a limited knowledge of the blues in high school, mostly absorbed from the blues played in the rock music of my generation. My exposure to and knowledge of blues and its history grew during my college years in Boston. Eventually, like a lot of the musicians I admired, I migrated west and wound up in San Francisco. Unfortunately, Bloomfield died before I had an opportunity to see him perform. But I regularly saw Elvin Bishop, Charlie Musselwhite and Nick Gravenites play in clubs around town, often in North Beach at the Saloon or the Chi Chi Club. Also, a lot of the guys from San Francisco’s psychedelic heyday: John Cipollina, Barry Melton, Sam Andrew, Jerry Garcia. Honestly, the music attracted me first. Then the story behind the music.

How did you get involved in directing the film?

The producers showed me a cut of a film they were not yet satisfied with. It was a concert film featuring the Chicago Blues Reunion band, and the backstory of its members. The producers came to me and asked if I could fix their film. I saw more value in starting over and keeping the best bits, but making a different film that better told the story. At some point early in the re-imagining of the film, the writer Joel Selvin, whom I have collaborated with in the past, came on as a producer and wrote a new outline, followed by an exhaustive script that became the blueprint for what we wound up putting together that became the final version of Born in Chicago. My filmmaking partner Christina Keating’s contributions cannot be understated, as well. We used lot of the interview material shot by John Anderson, the director who began the project, as well as some of the archival material culled for earlier cuts, but we jettisoned the original structure of hanging the story on top of a concert film.

We did a deep dive into what performances could be used and found some rarely seen material. Only a small bit of the original concert footage that was the spine of the film we inherited remains in the film now, as a coda at the end. The film that was a concert film became a historical documentary about the passing of the blues torch from one generation to the next. As a nice epilogue to the project, John recently completed and has released the original Chicago Blues Reunion concert as its own DVD, independent of this documentary.

What was your aim in making this film? What did you want people to know?

Our goal in this film is pretty similar to any project we take on, and that is: how can we tell this story in an entertaining way that informs the audience and holds their attention? What we wanted people to know is that Chicago was a very important place in the evolution of the blues, particularly post-WWII electric blues. And that although American middle-class white kids may have received their first taste of the blues from the British bands that embraced and interpreted the music, it was this group of young musicians who were taken in by the originators of Chicago electric blues and learned, not off of records imported from across an ocean, but rather at the feet of their heroes, and on their stages. These guys learned from the real deal, and the music they played had a greater authenticity and integrity.

Why did this happen in Chicago?

The migration from the South to the North by African-Americans to get jobs in the factories. That brought black culture to Chicago’s South Side and Maxwell Street. In fact, there were thriving blues scenes in Tennessee, Louisiana, Texas, California and elsewhere. But, what happened in Chicago was monumental, and greatly influenced the music everywhere.

The period footage is incredible. What was involved in tracking down and rounding up some of the rare footage?

Christina spearheaded our deep dive for archival footage, both performance and B-roll footage to give the story a sense of time and place. Some of the color 8mm home movie footage came courtesy of Sam Lay, the original Paul Butterfield Blues Band drummer, who had previously played with Muddy [waters] and [Howlin’] Wolf. I had used some of this footage in my Bloomfield film and it was already part of the footage we inherited with the project.

Related: When the Rolling Stones brought Howlin’ Wolf to American television

Was there anything that was previously elusive that you found and included?

Yes! The footage we used of the Butterfield Blues Band’s afternoon performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival had long been rumored to exist, but never previously seen. When it arrived on my desk for the first time I shed tears. For me it was like finding the Holy Grail.

Any favorite clips?

I love seeing the Goldberg Miller Band’s clip [with Steve Miller and Barry Goldberg]. Every clip we used of Howlin’ Wolf I find mesmerizing. And Bloomfield just kills it with D.A. Pennebaker’s footage of the Electric Flag from the Monterey Pop Festival.

From what you’ve learned from doing this film, what was the main reason so many young white musicians were attracted to the music of the older Black musicians?

Duke Ellington said, “There are simply two kinds of music, good music and the other kind…” I think that people are attracted to good music. These were young people who were hooked by the sound that these guys made. It took them out of their world to one they could only imagine. It was the beginning of a musical and cultural journey.

Every time we see Mike Bloomfield on screen, he’s electrifying. Specifically, what was Bloomfield’s role in spreading the blues to a larger audience, particularly young white people?

Michael Bloomfield was a fascinating person. He had a manic energy that turned some people off, but many people on. Not only was he incredibly gifted and practiced as a musician, he was a brilliant person who read everything and was incredibly charismatic. His guitar playing touched people, many of whom never knew who he was. His influence was tremendous, particularly on the promoters who booked him. He encouraged them to book Muddy, Wolf, B.B. [King] and their generation of original blues musicians to perform in the same venues. This not only helped the careers of his mentors, but helped teach a new audience about the source of this music that they already loved.

What about Butterfield? How did he and his band transform the music and its popularity?

As influential as they were at the time, it wasn’t reflected in record sales or box office receipts. Butter never attained the heights as Led Zep or the Animals. But the band was like the Velvet Underground in that regard. Maybe they only sold a modest amount of wax, but every copy sold inspired some young kid to join a blues band.

We hear a lot these days about cultural appropriation, but that term, or even the concept, did not exist at the time this music was being made. In retrospect, were the white blues musicians guilty of that or did they enhance the careers of the Black musicians whose styles and songs they built upon? And how did the Black artists feel about the white musicians moving into the blues?

First of all, the white kids didn’t quite crash the party as they were invited to be a part of the scene. Here is the thing about cultural appropriation: First it implies a theft of culture. There was no theft here. Butterfield, Bloomfield, Elvin [Bishop], Miller, Charlie ,[Musselwhite] Harvey [Mandel], Corky [Siegel]…these white cats were invited to play with their heroes because the older generation of Black musicians recognized in the young guys that not only did they have a true love for the music, they actually had chops and could hold their own on stage. These young guys lived with their heroes, broke bread and drank with them, babysat their children. They became friends and family, a mixture of cultures. They learned integrity from these guys. Second, in regard to cultural appropriation, there is an assumption of no payback. Quite the opposite happened in this story. Once the young white musicians (and recall that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and other bands were often multi-racial) started getting traction in their careers, they immediately paid it back by encouraging these venues to book the previous generation, which allowed them to have a much more fruitful career moving forward than they had been enjoying. No theft, and there was payback. So, no, there was no “cultural appropriation.” Culture does what it always does: it grows and adapts.

Watch the Goldberg-Miller Blues Band on Hullaballoo

You devote a good deal of time to Muddy Waters. He is often considered the epitome of the Chicago blues artist. Why was he so important, perhaps more so than anyone else, to the development of Chicago blues? What made him so emblematic of Chicago blues?

Muddy was not the first to plug in and play electric, but he was the first big star of that scene. He was so powerful and influential. His band became a training ground for so many great artists. I think beyond the music that can be heard on the grooves of the records he made, he projected an air of class and integrity. I think everyone looked up to him.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Electric Mud, the bluesman’s “psychedelic” album

Probably the next most important was Howlin’ Wolf. He was a very different kind of artist from Muddy. What did he bring to the music?

I think there was something mysterious and dangerous about the music Wolf made. Nobody could ever duplicate his singular voice. It’s as identifiable as B.B. King’s guitar. One note and you know who it is. I see Muddy and Wolf as the Yin and the Yang of Chicago blues.

Watch Howlin’ Wolf’s amazing performance on the U.S. rock TV program Shindig!, as guest of the Rolling Stones

What did you find out from the interviews in the film that you didn’t know before?

To be honest, I conducted no original interviews for this film. Most of the interviews were conducted by John Anderson or others prior to my joining the project. I did add to the mix interviews I had previously conducted for my Bloomfield doc; those included interviews with Bill Graham, Chet Helms, Jorma Kaukonen, Bob Weir, Al Kooper, Barry Goldberg, Charlie Musslewhite, Elvin Bishop, Mark Naftalin and others. I repurposed those interviews for this film to help flesh out the story. The value of hanging on to your old interviews!

What was the source of the Dylan interview about Bloomfield?

That was conducted by Dylan’s manager, Jeff Rosen, and previously used in Martin Scorsese’s Dylan documentary. Jeff was gracious to grant us permission to use it in our film.

And what was the source of the Keith Richards interview?

I’ve met Keith previously and interviewed him for our documentary about Bert Berns. He was articulate, fun and just what you’d hope he’d be, a nice guy. But, for this film his interview came from the BBC archives and licensed for use here.

You devote a lot of time to Chicago musicians moving to the Bay Area. Why do you think that happened?

I think they found opportunities there that didn’t exist in Chicago. The weather was better, the girls were pretty, psychedelic drugs fueled the scene and there was a freedom that existed nowhere else. There was a cultural revolution that was centered on the West Coast, and they wanted to be a part of it. I moved from the east to San Francisco 13 years later and the pull was still quite powerful from the comet that blew through town a decade earlier.

With so many of the formative blues figures now deceased, did that present challenges to you as a documentarian?

It always presents a challenge to tell a story about someone who has passed. But, I’m a storyteller. I always say, you can’t make a film out of material that doesn’t exist, so you figure out how to tell it with material that does exist. AI is changing that, but I think filmmakers need to be very careful about how that technology is used moving forward, and maintain integrity. No AI was used in the making of this film. Although, Jimmy Vivino seemed to channel Hubert Sumlin and others in the original music he made with Barry Goldberg for this film.

You talk about blues losing ground to R&B/soul in the ’60s. Why did that happen and what did that do to Chicago blues?

Al Kooper has told me that the purpose of popular music is to piss off your parents. By the cusp of the ’60s young African-Americans were hip to Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, James Brown, the music of Motown and Stax. They didn’t want to listen to their parents’ music any more than I wanted to listed to Benny Goodman or Frank Sinatra when I was a kid. That was my parents’ music. Blues belonged to the older generation of African-Americans. What it did was make the scene ripe for the entrance of these white kids who didn’t really fit in at home, but were looking to their blues mentors for direction and acceptance.

Having Dan Aykroyd narrate the film was a perfect choice. Did you find that he was truly into this music and knew his stuff?

I was not surprised at all to find Dan very well informed on the subject. To be honest, when it was originally suggested that Aykroyd narrate the film I rejected the idea, as I feared an Elwood Blues reading might degrade from the film’s authenticity. Then, after thinking about it I realized he could be great if he did it straight. I spoke to his manager and said that I’d prefer that Dan not read the narration in the Elwood Blues character. I was assured we couldn’t afford Elwood Blues even if we wanted him. Dan was totally prepared and very professional. He wanted was open to direction from me, though honestly, it was rarely needed. One of the easiest narration recording sessions I’ve ever done. I think he did a great job.

What is the legacy of Chicago blues music? Where did it leave its mark that we can still hear and feel today?

I think the days of Chicago blues being popular music has passed, but it’s alive and well. I was just in Chicago a couple of times recently and there is a robust music scene there. The blues will always have its audience, and will continue to be discovered and evolve for generations to come. And always, in the DNA of that music will be the influence of Muddy, Wolf, their contemporaries and disciples.

Watch the official trailer for Born in Chicago

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

5 Comments

I want it! Where’s the info on where to buy a DVD of it?

It is not yet available in DVD.

Another great documentary covering the Chicago blues scene is Horn From The Heart: The Paul Butterfield Story, available on Prime and other streaming platforms.

Yes! When will it be available for purchase on DVD?? I live in Chicago and can’t get it!

We will announce it on Best Classic Bands when it is available on DVD. Keep checking in!