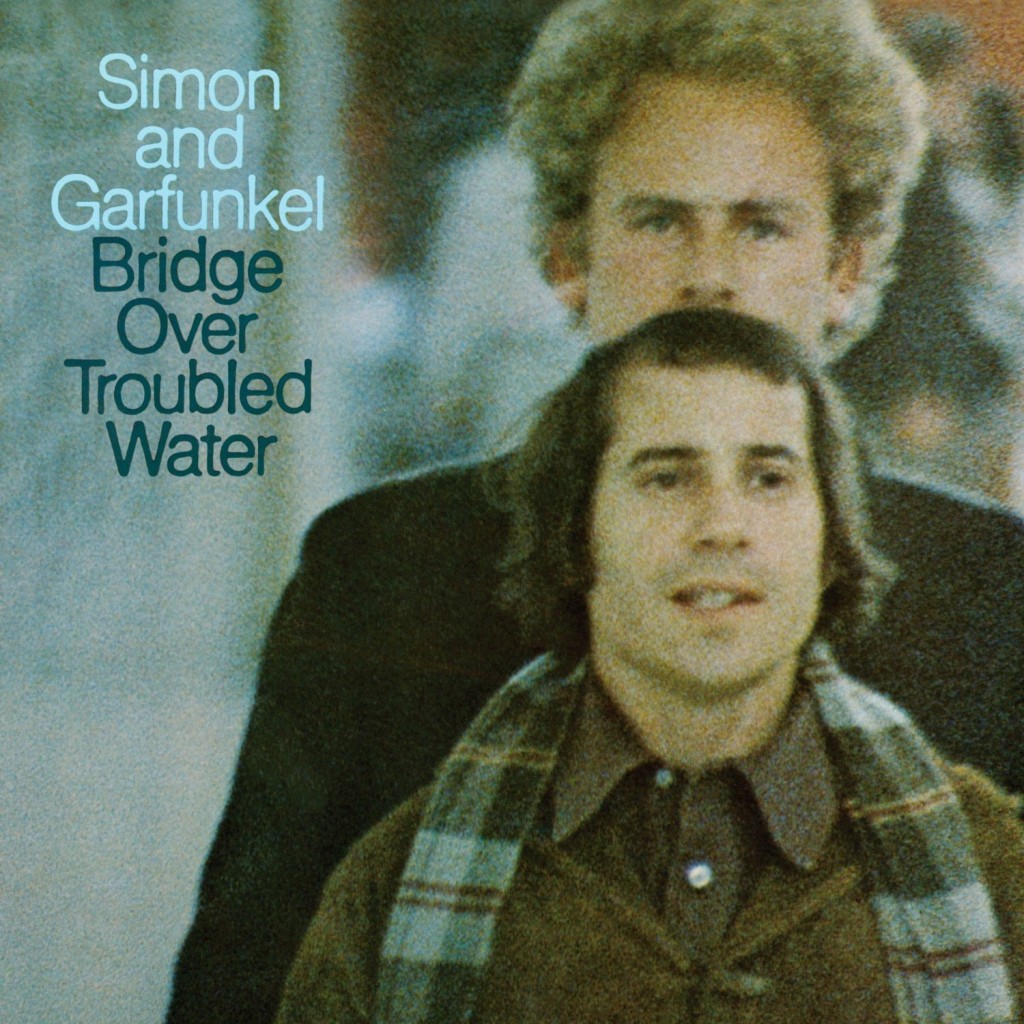

Bridge Over Troubled Water represents both culmination and swan song for Simon and Garfunkel’s reign as ’60s rock’s most accomplished duo. Painstaking in its creation, their fifth studio set, released on January 26, 1970, proved a commercial juggernaut, the year’s bestselling album and CBS Records’ top seller for the next decade before being surpassed by Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982. Yet during its year-long gestation, the partnership forged by friends since childhood in Forest Hills, N.Y., was fraying. By the time Bridge swept the 1971 Grammy Awards, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel had effectively parted ways professionally.

Bridge Over Troubled Water represents both culmination and swan song for Simon and Garfunkel’s reign as ’60s rock’s most accomplished duo. Painstaking in its creation, their fifth studio set, released on January 26, 1970, proved a commercial juggernaut, the year’s bestselling album and CBS Records’ top seller for the next decade before being surpassed by Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982. Yet during its year-long gestation, the partnership forged by friends since childhood in Forest Hills, N.Y., was fraying. By the time Bridge swept the 1971 Grammy Awards, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel had effectively parted ways professionally.

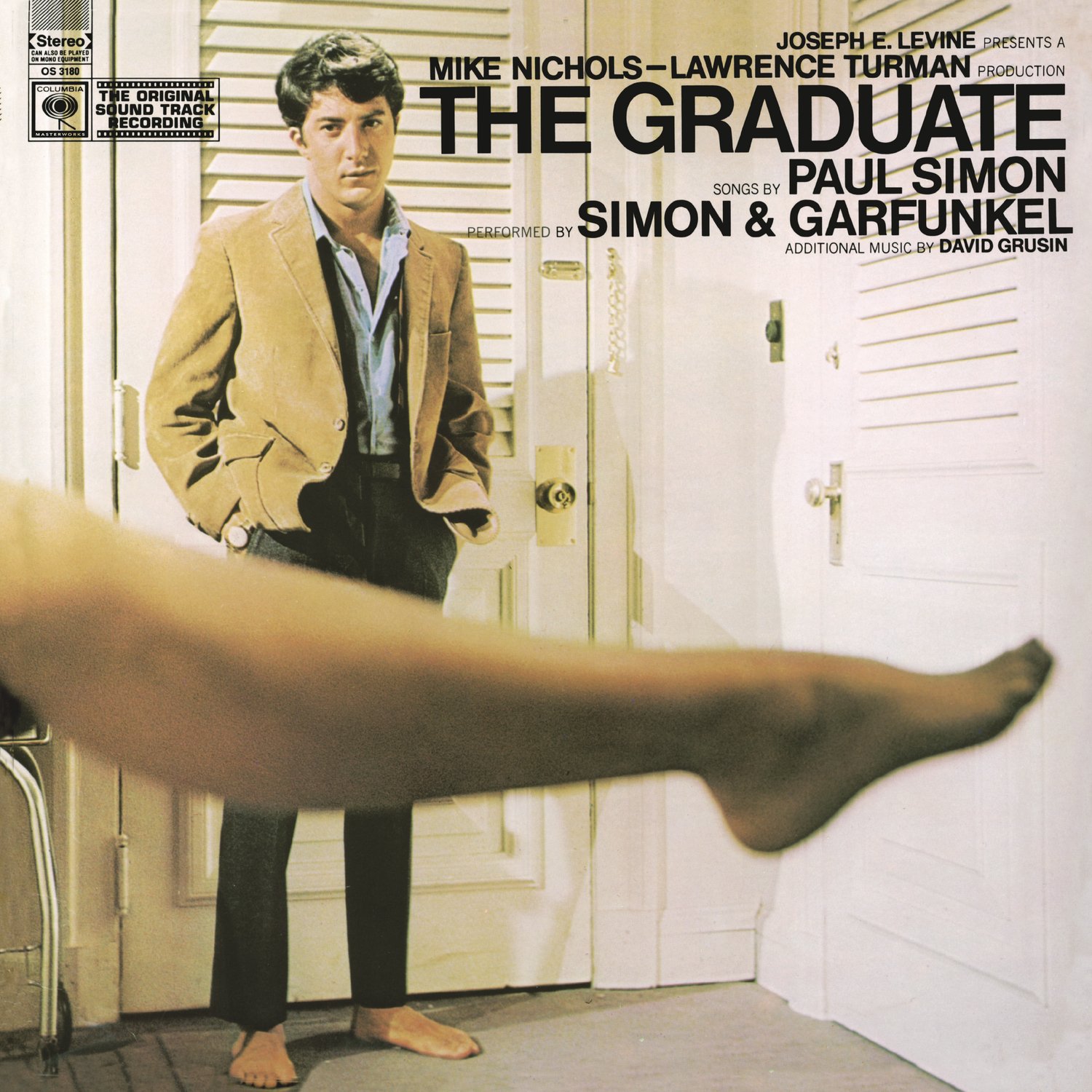

In hindsight, director Mike Nichols was an unwitting catalyst for the split. It was Nichols who tapped them for The Graduate, his acerbic 1967 comedy, integrating Simon and Garfunkel’s pensive folk-rock songs as interior reflections of its hapless protagonist. CBS Records president Clive Davis pressed for a soundtrack hit despite the duo’s concern its release would undercut their impending fourth studio album, Bookends, but where they feared competition, he saw synergy in its generational reach to both moviegoers and boomer fans.

Far from handicapping their ambitious studio full length, The Graduate effectively bridged the projects. The film’s most prominent new Simon song, a breezy guitar instrumental originally titled “Mrs. Roosevelt,” appeared in two brief versions saluting the film’s older seductress, Mrs. Robinson, with only its infectious “deet-de-deet-deet” vocal riffs. Released as a single, the completed version of “Mrs. Robinson” topped the singles chart and went on to win two Grammys, while both the soundtrack album and Bookends reaped platinum glory, cementing Simon and Garfunkel’s own graduation to new status as peers to erstwhile idols Bob Dylan and the Beatles.

As they began planning their next album, Nichols was grooming his screen version of Joseph Heller’s classic anti-war novel, Catch-22, and surprised his Graduate hitmakers by offering both acting roles. Garfunkel would play doomed bomber pilot Captain Nately while Simon was pitched a smaller role. When the latter part was cut, Simon gave Nichols and Garfunkel his blessing to proceed without him. The movie would be shot on location in Mexico, standing in for the novel’s Mediterranean island, thus tethering Garfunkel to the West Coast while Simon remained in New York.

Logistics thus proved problematic as Catch-22 ran over schedule, further tipping control over album sessions toward Simon and engineer and co-producer Roy Halee. Their two previous albums reflected the troika’s escalating studio ambitions, spurred by the Beatles’ and Beach Boys’ studio innovations and audible in the conceptual premise and sonic experimentation on Bookends. No track would demonstrate Simon and Garfunkel’s aspirations more boldly than the project’s first completed track and their next single, “The Boxer.”

The song’s flowing pace began in Nashville, where Simon and Music Row stalwart Fred Carter Jr. wove a graceful latticework of fingerpicked acoustic guitars for the ballad’s musical core. To that foundation, Simon, Garfunkel and Halee built a magnum opus using three studios, 100 hours of studio time and pioneering 16-track coverage hacked by syncing two eight-track machines. An anthem to survival, the song builds toward a gentle instrumental bridge of pedal steel guitar and piccolo trumpet before expanding its mournful “lie-la-lie” refrain to symphonic scale, unleashed by the thundercrack of Hal Blaine’s echo-drenched drums and a melodramatic swell of strings and horns. Any resemblance to “Hey Jude” isn’t coincidental.

Released in March 1969, “The Boxer” was their most audacious single to date, breaking into the top 10 despite its five-minute-plus running time and fusing the acoustic folk sensibility of their early hits with cinematic pop. Contrasting its somber intensity was a giddy uptempo B-side romp, “Baby Driver,” propelled by walking bass, strutting saxophones and sonic nods to the Beach Boys in its bass harmonica accents and “bomp-ba-bomp-bomp” backing vocals beneath its automotive double entendres. A palate cleanser for both single and album, the song would enjoy an outsized afterlife as inspiration and title for Edgar Wright’s ingenious 2017 action film, a cinematic mixed tape spliced with car chases.

Production of subsequent songs would open Bridge Over Troubled Waters’s design to variety rather than conceptual unity. Retaining the L.A. Wrecking Crew’s rhythm section of Blaine, bassist Joe Osborn and keyboard player Larry Knechtel for the third consecutive full-length, Simon and Garfunkel shifted stylistic gears across 11 tracks, among them a haunting foray into Andean folk music foreshadowing Paul Simon’s subsequent solo investigations of world music.

For “El Cóndor Pasa,” Simon adapted a folk song he had first heard by Los Incas, adding English lyrics and inviting the Peruvian ensemble to add indigenous flutes, percussion and guitars to evoke its timeless setting. An erroneous initial attribution as a traditional folk song prompted a suit by the family of its composer, Daniel Alomia Robles, amicably settled to recognize Robles’ original 1913 creation. Released as a single, the track was an international hit, reaching #1 in seven countries and breaking into the top 20 in the U.S.

More conventional pop prevailed on “Cecilia,” another successful single, and “Keep the Customer Satisfied,” neither of which would age as well as two deeper cuts with autobiographical details balancing admiration with wistfulness. Tensions between them stretched back across years, from their short-lived teenage bids for rock ’n’ roll glory as Everly Brothers wannabes Tom and Jerry through Simon’s separate Brill Building and British folk scene adventures. Even as Bookends was reaching record stores, Garfunkel penned a deeply sad letter venting years of perceived grievances documented in Robert Hilburn’s biography of Simon.

Yet affection, not rancor, warms Simon’s lyrics to “The Only Living Boy in New York,” directly addressing his partner by his teenaged stage name at this juncture in their partnership:

“Tom, get your plane right on time

I know your part’ll go fine

Fly down to Mexico…”

Simon’s conversational vocal tempers its warmth with a melancholy admission, “Half of the time we’re gone but we don’t know where,” before slipping into a hushed yet majestic choral section given vast sonic space above Joe Osborn’s melodic, plangent bass guitar foundation. One of the album’s most beautiful moments, the track feels like a benediction, answered by Garfunkel himself in its closing refrain, “Here I am.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, Paul’s 1972 solo release

Simon proves more detached and lightly veiled on “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright,” a farewell saluting Garfunkel’s earlier architectural aspirations while signaling Simon and Garfunkel’s imminent split, a message Garfunkel evidently didn’t recognize until years later. Then again, during the album’s production Garfunkel accepted a role in Mike Nichols’ next comedy, Carnal Knowledge, a move infuriating his partner.

If Bridge Over Troubled Water was produced under combat conditions, its title single would emerge as one of the most celebrated of the era. The last song recorded but first completed, the piece conjures a luminous pop gospel testament Paul Simon crafted from the bones of a Bach hymn and lyrics directly inspired by the Swan Silvertones’ “Mary Don’t You Weep,” gifting Garfunkel with one of his most incandescent solo vocals. Framed by Larry Knechtel’s elegant piano arrangement and capped by a dramatic orchestral crescendo, the record would prove Simon and Garfunkel’s signature achievement—their biggest single hit, earning four Grammys on its own including Record of the Year and Song of the Year; the LP added Album of the Year and Best Engineered Recording to their haul of gilded gramophones. Like “The Boxer,” the song would become one of Simon’s most widely covered compositions, with those songs anchoring its eventual sales bounty of 25 million copies sold.

For CBS, Simon and Garfunkel’s sales cast a long shadow over Paul Simon’s determined reset as a solo artist. When his self-titled first album for Columbia fell short of platinum certification during its initial release, that commercial calculus seemed daunting in the wake of Bridge and Art Garfunkel’ celluloid notoriety, yet in its intimacy, eclecticism and musicianship, Paul Simon heralded a solo career that would ultimately rival the duo’s commercial triumph and surpass it for artistry.

The album, and other Simon & Garfunkel recordings, are available to order here.

Related: The #1 albums of 1970

Watch “Bridge Over Troubled Water” from The Concert in Central Park reunion in 1981

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

3 Comments

Brilliant let’s have more please

Neil

Whatever genre of music you favour Bridge Over Troubled Water has to be recognised as a masterpiece in so many respects The songwriting, the production, the musicianship make this album a standalone in 20th century popular music. It may have marked the end of the short run of studio albums by the duo but Paul Simon’s talent as a musician, songwriter and performer soared with a subsequent catalogue of work that truly places him alongside the Gershwins, Lennon and Mcartney and Dylan. For those who find the title track a touch “sacharine” listen to the Aretha version – inspirational!

Simon did not ‘surpass’ what S&G did. The level was maintained by the best work that both Simon and Garfunkel did subsequently but no, it did not surpass. And that’s not a slight on their later careers. You can’t place greatness over other greatness, you can only place greatness over not so great.