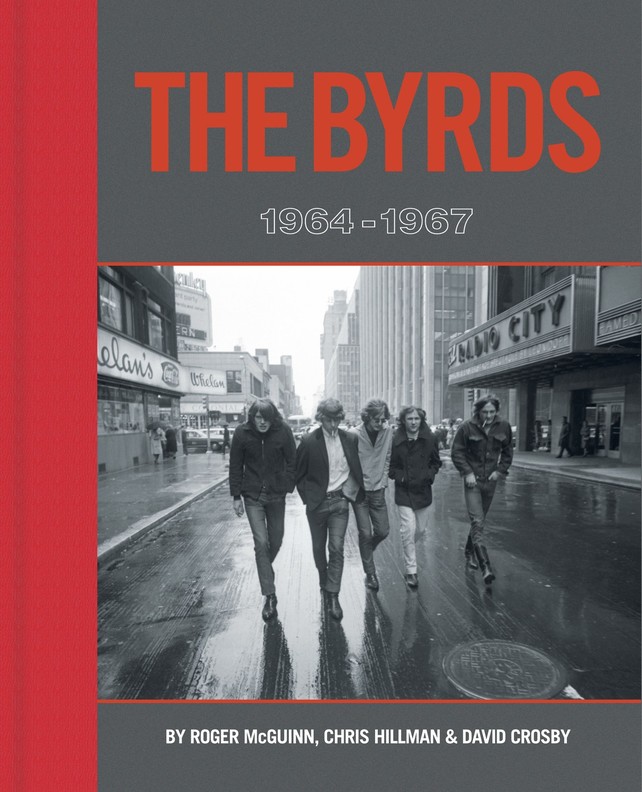

A large-format, 400-page collectible art book from BMG, The Byrds: 1964-1967, curated by the band’s three surviving founding members, and available in three versions, including a Super Deluxe Limited Edition signed by Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman and David Crosby, was published on Sept. 20, 2022.

Featuring more than 500 images from legendary photographers such as Henry Diltz, Barry Feinstein, Curt Gunther, Jim Marshall and Linda McCartney, the book also includes restored images from the Columbia Records archives and the personal archives from the band’s original manager, Jim Dickson.

This century I’ve interviewed Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman and David Crosby. My first interview with McGuinn was in 1974. Hillman and I spoke a few times over the last couple of decades. My brief Crosby interview was in 2021. [Croz died in Jan. 2023, four months after the book was published.]

Following are excerpts from those interviews.

Roger McGuinn Interview

Best Classic Bands: What are your thoughts on The Byrds’ unique vocal blend?

Roger McGuinn: We sang together well. I give the credit to Crosby. He was brilliant at devising these harmony parts that were not strict third, fourth or fifth improvisational combination of the three. That’s what makes the Byrds’ harmonies. Most people think it’s three-part harmony, and it’s two-part harmony. Very seldom was there a third part on our harmonies.

“My Back Pages,” the Byrds’ cover song from Bob Dylan heard on Younger Than Yesterday, still garners a lot of radio airplay. How did you come to record it? You had done many previous Dylan songs in your repertoire.

I was driving my Porsche up La Cienega, and got around to Sunset, and Jim Dickson, our former producer and manager, signaled for me to roll my window down. He had been fired by the Byrds, shortly before that, but he still liked us, or some of us. He pulled up in his Porsche, and said, “Hey, Jim. You ought to record Dylan’s ‘My Back Pages.” I said, “OK. Thanks.” The light changed, I drove back up into Laurel Canyon, and pulled out the Dylan album that had “My Back Pages” and learned it.

I then took it to the studio and showed it to the guys. Crosby hated it. He was mostly upset because he wasn’t getting his own songs on the album, and [that’s] the reason why he left the band. There was a rift in the band, and he wasn’t getting as many as some of us. So anyway, I liked “My Back Pages” and don’t remember any resistance from anybody else in the band, just David.

It was Dickson’s suggestion and I hadn’t thought of it as a song for the Byrds repertoire. I liked the wisdom of the song; it’s a very insightful song on what happens when you think you’re so knowledgeable and wise when you are real young. And then when you get a little older you realize what you didn’t know.

Dylan’s stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the “Shakespeare of Our Time.” It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on Kerouac and Ginsberg. The baton had been passed. I remember Ginsberg said, “I think we’re in good hands.” We did “Chimes of Freedom” at Monterey Pop. I loved the imagery. You can’t pin it down as a peace song, or whatever, but it’s got overtones of that. It’s brilliant. I just identified with it and could relate to it.

The Byrds performed Dylan’s “All I Really Want to Do” at a Shindig! taping.

I love “All I Really Want to Do.” It’s kind of a simple little love song, but it’s got a really sarcastic, whimsical attitude. He doesn’t want to be hassled. He just wants to be friends. We changed the arrangement from the 3/4 time to 4/4 time. We became his “unofficial, official” band for his stuff. I remember when Sonny and Cher got the hit with “All I Really Want to Do,” Dylan went, “Oh man, you let me down…” Normally, a writer would be happy to get a hit with his own songs. Who cares who did it? He was on our side.

“So You Want to Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star?”

Chris and I knocked off “So You Want to Be A Rock ’n’ Roll Star” in very late 1966 at his house. It really wasn’t about the Monkees. We were looking at a teen magazine, and noticing the big turnover in the rock business, and kinda chuckling about it. A guy was on the cover that we’d never seen before and we knew he was gonna be gone next issue. A funny little song. People didn’t know how to take it. We just meant it as a satire. We got along well and we wrote well. Actually, Crosby and I wrote well too for a while together, and so did Gene [Clark] and I. We had some good times writing songs.

Chris Hillman played us “Have You Seen Her Face” in the studio and we cut it. We weren’t into making demos back then. Demos came along in the ’80s. (laughs). Chris Hillman is a very gifted musician. The way he transitioned from mandolin to bass in a very short time was amazing. I don’t know if he was completely influenced by McCartney but he had this melodic thing, I guess more from being a lead player. He incorporated a lot of leads into his bass playing.

David Crosby brought some jazz influences into the mix.

David Crosby and I, on our early stuff like “The Airport Song,” I enjoyed the direction, that was sort of jazzy. He’s an incredible singer for harmonies and he’s written some wonderful songs as well. A good songwriter. I also really appreciated his rhythm guitar work. I thought he had a great command of the rhythm part of it, and also finding interesting chords and progressions. He was the one who, in “Renaissance Fair” and “Tribal Gathering,” found the off-the-beaten-track chord changes that were really cool.

Chris Hillman Interview

Best Classic Bands: Why does the music of the Byrds still hold up?

Chris Hillman: The ’60s were wonderful. What holds up from that era are melody and lyric. In the Byrds, our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, “Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in 40 years, that you will be proud to listen to.” He was right.

I think that’s a big part of it and it was real and so honest. The record companies were run by music people, people who loved music. It was not a corporate monster. They’d sign you and you’d be on the label for three or four albums.

When you heard a new song on the radio the melody would catch you right away. You might hear a couple of lyrics, if they’re strong and really saying something, that was it. The Beach Boys: Melody, melody, melody.

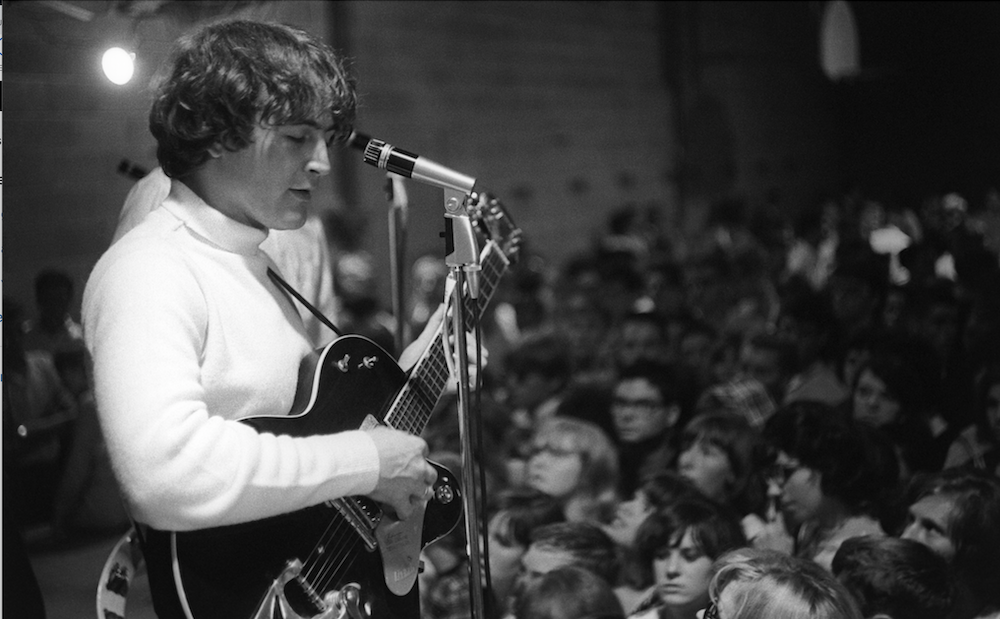

Lots of photos exist of the Byrds. Visual documentation was important in that era.

Lots of photos exist of the Byrds. Visual documentation was important in that era.

Before I was even in the Byrds, the first record I ever did was with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers, and we did the entire album in four hours. It was a good band. We went out to Griffith Park in Hollywood and lined up in a color photo shoot, appropriate for our age.

When the Byrds came along, we did one of our very first publicity black-and-white shots and we’re in suits. I remember us doing that photo in the daytime and it might have been at Shelly’s Manne Hole club in Hollywood. There was an older guy at that session doing photos. It was so early it might not have been an [official] Columbia publicity photo.

The Columbia recording studio had a history going back to radio broadcasts with Fred Allen and Jack Benny.

Columbia was a union room. The engineers had shirts and ties on. Mandatory breaks every three hours. Record producer Terry Melcher was a good guy. I didn’t really get to know him. I was shy. Columbia was comfortable to record. I will say this: on the Byrds’ albums, I was not mixed back. All five of us were learning how to play, coming out of the folk thing and plugging in. Roger was the most seasoned musician, and we all sort of worked off of Roger. He had impeccable, great sense of time, that minimalist thing of playing that was so good. He played the melody. Our first album cover was shot by photographer Barry Feinstein, who was an old friend of Jim Dickson.

You really blossomed on Younger Than Yesterday.

I really started writing songs after Crosby and I were on a Hugh Masekela session with these South African musicians, way ahead of Paul Simon. One of them was a piano player named Cecil Barnard was very inspirational. And, Letta Mbulu, a wonderful singer. All the musicians were South African with the exception of [drummer] Big Black. I played bass on a demo session. And David was a good rhythm guitarist.

I went home and wrote “Time Between” and “Have You Seen Her Face,” influenced by a blind date Crosby had set me up with, along with other young ladies. There was something that connected with me and that was where I came out of my shell with that session. I came home and wrote songs that entire week after that session.

The Byrds and Hugh Masekela played together at the 1967 Monterey festival.

Hugh Masekela at Monterey was one of the highlights, and recording earlier with him was one of the highlights of my life. At Monterey we did Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom.” I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs and he was just peaking then.

At Monterey we did a repertoire of what we were currently recording and other songs. Gene Clark had just left and had so many good songs that lent themselves to the Byrds’ concept sound that when he was gone, we continued to do those songs.

David Crosby Interview

Best Classic Bands: You always had a relationship with jazz. You saw John Coltrane play live and spent a lot of time at Dick Bock’s World Pacific studio. Bock issued many legendary jazz albums and titles from Ravi Shankar.

David Crosby: I was a young folkie musician. My brother [Ethan Crosby] played a lot of ’50s jazz. I got turned on to jazz long before I got turned on to pop or rock ’n’ roll. They played me Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Bill Evans, all of those guys in the late ’50s. And more obscure stuff like Cal Tjader. J.J. Johnson. All jazz.

I got to a point where my head started to open up a bit and I started playing guitar and getting more interesting on it. I started to listen to pop music and I realized those chords that I really liked were a little further along. I started hearing some people using chords like that, and I wanted to go that direction.

When we started the Byrds, man, there were other people around town. We’re tallkin’ primitive shit, guys dancing on their amps in uniforms. I mean, come on (laughs). This is a different world. Then I hear Steely Dan. Man, do I wish I was in that band. And other bands came along as well. Michael Hedges was another one. Strongly jazz-influenced but strongly classically influenced too.

Your tune “Triad,” about a threesome and sexual freedom, was presented to the Byrds in 1967 for potential inclusion on the LP The Notorious Byrd Brothers, recorded and rejected. It later surfaced in 1971 on CSN&Y’s 4 Way Street. In 2006, the Byrds’ recording of “Triad” appeared on the Columbia/Legacy label’s There Is A Season box set. Why was that song considered so wrong for the Byrds by the others in the band?

The reason the French call it ménage à trois is they’ve been doing it for a long time. It’s not controversial. I think there are people who are very straitlaced, some for religious reasons and some of them because they are squares. And for them the idea of three people making love at the same time is not only strange but outrageous, terrible and offensive. I don’t feel that way. Those things are very deeply seeded, people’s reactions to sex and religions.

Listen to the Byrds’ version of “Triad”

Bonus Video: Watch the Byrds perform “Chimes of Freedom” at Monterey

Related: Our Album Rewind of the Byrds’ 1965 LP, Mr. Tambourine Man

3 Comments

It’s obvious from what we’ve heard from him, and from what so many of his former bandmates have said that David Crosby is a uniquely talented musician, songwriter, and singer. It’s also equally obvious, hearing secondhand from every one of those same bandmates, that the price of collaborating or being involved with that talent is pretty high, and it appears, in most cases, untenable, as none of his former bandmates not only don’t want to work with him again, but they also don’t want anything to do with him at all. That uniformity pretty much takes the question of subjective opinions out of play. But it’s not unusual to find people who don’t play well WITH others. As Crosby has since gone on to create a remarkable series of universally lauded albums, one has to assume he does just fine, if he’s the boss. A band is a difficult thing for mutually creative people to be in together.

“the band’s three surviving founding members” … Now only two surviving founding members.

Jefferson Airplane recorded the best version of Triad, bar none.