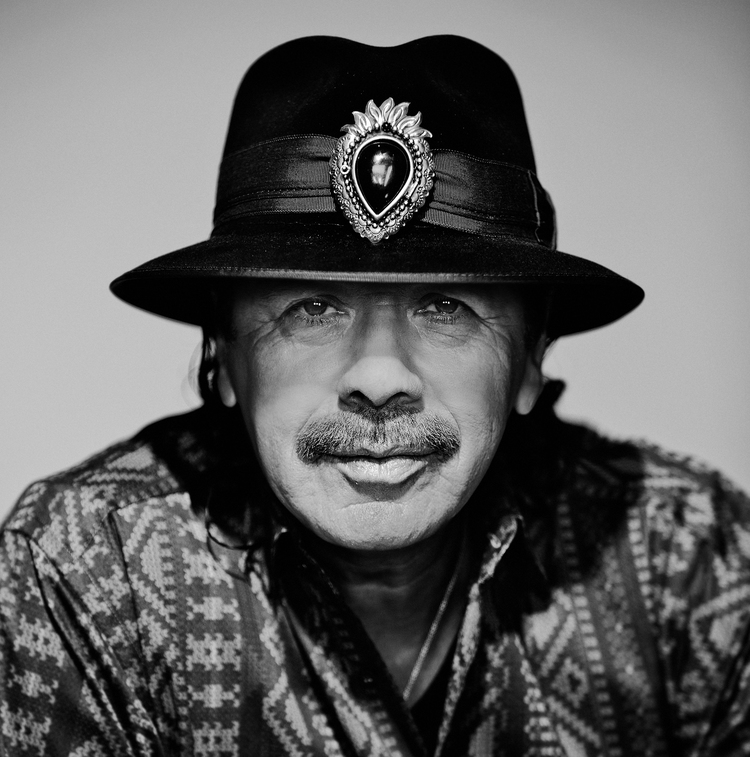

On July 20, 2017, Carlos Santana turned 70. That night, he and his band—Santana, of course—performed in São Paulo, Brazil, one of 164 dates they played last year. More than a half-century after he put together the first incarnation of Santana, the guitarist is still doing exactly what he’s always wanted to do, taking his music to the people. “I’m really grateful because I know that a lot of musicians didn’t make it,” he says in the following interview. It’s a characteristically generous and honest statement from an artist who never holds back.

This conversation took place in 2010 but has, until now, remained largely unpublished.

Who are some of the guitarists who’ve been most important to you?

Oh, Jimi Hendrix. He understood the whole spectrum of sound as a visual thing. I did get the chance to see Cream when they first came to San Francisco, and of course I was into B.B. King and Michael Bloomfield and Peter Green, but somehow when Hendrix came it was like [John] Coltrane in a sense in that he had a broader vision. It was almost like the difference between 8 millimeter and Cinemascope Surround Sound in 3-D. He just brought a whole other kind of brush. And I was there. I heard him play at least three times in person and I couldn’t believe it. There are certain people on this planet and you just recognize them as a supreme standard of excellence. There’s Bruce Lee, Evel Knievel, Tony Williams, Miles [Davis], Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Hendrix, Wes Montgomery. If I was running [a store] I would have a corner called the genius corner. You go to that corner you’re gonna find Igor Stravinsky and James Brown.

In 2010 you released an album called Guitar Heaven, where you covered songs by everyone from Led Zeppelin to the Stones, the Doors, Deep Purple and more. Was there one message in those classic rock tunes that spoke to you?

The message from the ’60s was consciousness revolution. All those songs, from “Riders on the Storm” to “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” were probably conceived with…I’m not going to call it drugs because that would be demeaning, but I will say some mind-expanding medicine. There’s a difference. Drugs, humans make in a laboratory. Medicine, mother nature makes from the ground. The sun tells the plant what color, what texture, what aroma, what flavor to be, and especially when it dries, you make tea out of it and this plant knows where to go: your kidneys, your lungs, your liver. It’s amazing that everything knows what to do and why. To me, that’s how music should be, just like a beam of light, with some earthy notes.

Listen to Carlos Santana covering Hendrix’s “Little Wing”

Related: Links for 100s of concert tours, including Santana

Can you feel as close to a cover song as you can to something you’ve written?

I think whether it’s George Gershwin or the Beatles or anything, when you hug someone you hug them full-on. It’s a complete, thorough hug. That eliminates any distance. It doesn’t matter who wrote it if you eliminate the distance between your heart and the song. I mean, Miles Davis, the way he played “Summertime,” which George Gershwin wrote, when you hear it, it sounds like Miles Davis.

When you’re creating music, do you have to commit yourself to it totally?

Yes, because in order to be free, like John McEnroe or anyone like that, at their peak you do have to put in the discipline. Jimi Hendrix went to the bathroom with the guitar on. He was eating and cooking and ironing—he wouldn’t let go of the guitar. Same with Coltrane. The guitar becomes like your lungs—you don’t even think about it anymore. If you have to think about it, there’s already distance. This music should just flow. It’s like opening a faucet and the water pours out. It should be that natural.

You’ve always taken a lot of musical risks. Early in your career you made albums with jazz artists like Alice Coltrane and John McLaughlin, which your fans probably did not expect.

That’s the beauty of it. I think every artist needs to commit career suicide once in awhile—every three years.

Watch Santana and John McLaughlin reunite in 2016

You’ve been using many guest artists on your albums since Supernatural in 1999. Why does that appeal to you at this point more than just going into the studio with your band?

The appeal is honoring and celebrating all of these people. I’ve been doing this since ’67, with [African drummer] Olatunji or Michael Bloomfield. It’s not a shtick or a gimmick for me. People think, “Oh, Santana’s gonna wear it out, inviting so many people to his albums.” But I’m in this planet and I’m playing for people. Everything is a conscious decision. I made a conscious decision to get away from radio from ’73 to 1999. I knew that I was going to go into Alice Coltrane territory or Miles territory. That music isn’t on the radio except for college stations. But when I had children, they wouldn’t hear our music on the radio unless it was oldies but goodies, so we hooked up with Clive Davis and he started making a bunch of phone calls and before I knew it everybody wanted to play with me: Lauryn Hill, Dave Matthews. They all had a certain conception about me, and I feel really grateful that all of them brought the songs, their heart, their spirit. Supernatural was a win-win situation for people on the planet and accountants, lawyers, the IRS—everybody! I think the main thing is focusing on soulful, heartfelt service. What you do and what I do is a service to humanity—it’s either a service or a disservice.

Related: A conversation with original Santana drummer Michael Shrieve

When you play live with Santana, you’re very generous–you always allow the other players to shine. It’s a very democratic band; you’re not a typical frontman.

The thing about our band is we use the songs as vehicles to trampoline and catapult ourselves to this other place. Certain musicians use their musicians as a backdrop for themselves. I do the opposite. I expect the musicians that I’m surrounded by to attack ferociously—all of them, at the same time sometimes. When you see Santana it’s like seeing a three-ring circus with lions, elephants and tigers and they’re all hungry and want to be fed. It’s not just the ringmaster. You can only see the ringmaster for so long before you get bored.

Watch Santana perform “Black Magic Woman” in 1970

How much of that is because you’re not the singer? That takes the focus off of you and spreads it around to the others in the band.

I’m grateful for how God made me. I mentioned to someone, “You write all the songs, you play all the instruments, you engineer and you produce. Are you gonna buy the CDs too?” After awhile, when do you open your heart and let God come in through people?

How has your approach to the guitar changed over the years?

I used to look at my guitar like it was building blocks and created with a hammer and nails and learning how to do something. I don’t look at it like that anymore. I look at it more like drinking water. Water is going to go into your system and then you’re gonna sweat it out. Again it comes back to trust. You trust your fingers, you trust your heart and once you tune the guitar you trust that you’re going to say something soulful and significant.

You’ve played at Bethel Woods, which is on the site of the Woodstock festival. What was it like to be back in that place?

It made me feel really grateful that that was ’69 and I’m here now and the band is stronger than ever. I’m really grateful because I know that a lot of musicians didn’t make it. [Others] might still be here but they’re not in a condition to play anymore like they used to. And I could actually hear it. I closed my eyes and I could hear the roar of the crowd through Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Who and of course us. It made me feel really grateful again that I was at ground zero of peace and love.

Watch the classic Santana Woodstock performance of “Soul Sacrifice”

What are your fondest memories of those early days, playing the Fillmore in San Francisco and all that?

One word is self-discovery. We were discovering ourselves through the hearts of Tito Puente, B.B. King, Miles Davis and Sly, Jimi. All of us were on a quest of self-discovery. Some people would only discover certain things and they would be very guarded and that’s all they would want to learn. I didn’t want to be stuck with anything. I like life, so I can go from [Thelonious] Monk to John Lee Hooker to Tito Puente or Olatunji. I just love life and music. Some people get a Ph.D. to be a doctor of the toe; they only want to know about the toe. I need to know the whole body: the eye, the ear, the heart, the lung and the fingers, not just the toe.

Related: Santana/Journey keyboardist Gregg Rolie interview

What was your relationship like with [the late Fillmore promoter] Bill Graham? What do you remember most about him?

Bill Graham was a dear friend and brother who invested in me, beyond my band, because he knew the band was gonna break up. He knew the band was only gonna last three years. Then everybody recognizes you and your head gets so big and the band breaks up. But he could see something in me for the long haul and he stayed with me. Till the day he died he always wanted to be my personal manager. I was very gracious to say no because I didn’t want to ruin the relationship. Like Clive Davis, he was very set in his vision. Clive is more flexible. Bill was a little more cement in certain ways and I didn’t want to break the bond of friendship. I told him, “Bill, this is my relationship with you. I’ll let you be in my dream if you’ll let me be in yours.” Bob Dylan said that. That’s about it. I don’t want a dictator in my life telling me how and why and making me feel guilty if I don’t do what they tell me.

During the early ’70s, when you became a disciple of Sri Chinmoy and recorded with John McLaughlin, how did your growing interest in spirituality affect the music?

It affected me a lot because I got higher than what I was taking back then. I was listening to Coltrane and Paramahansa Yogananda and Martin Luther King and Mahalia Jackson and all of a sudden I was higher than the drugs. So I quit smoking pot, from ’72 to ’81. It was kind of like a boot camp. It was very disciplined: get up a certain time every morning and meditate, only eat certain kinds of foods, always read books that keep your consciousness from being vulgar or gross. I don’t regret it because I feel that it made me very elegant.

How do you still apply those lessons in today’s world?

It gives me an extra wind. Whenever I feel my body is trying to convince me that I’m tired, I change the way I breathe, change the way I think and I get another pocket of air and find another gear. I tell you, most people that are my age, they don’t sound or look the way I do. They walk like they’re ready for the home.

Do you do anything special to keep yourself in shape besides playing music?

Do you do anything special to keep yourself in shape besides playing music?

I do read a lot of spiritual books and I listen to a lot of music that keeps me—this is [wife] Cindy [Blackman Santana] and my favorite word—pristine, with purity and innocence. Like when you watch the little hands and fingers of an 8-year-old child that doesn’t know how to fake or connive, that’s just purity and innocence. Those things exist and like water, if you drink it every day, it’s going to prevent you from being cynical or crass, vulgar or predictable. All that stuff is poison for your soul. If you repeat being pristine with purity and innocence, those words have power.

Is that how you’ve managed to remain so positive all these years, despite everything that goes on in the world?

Pretty much, yeah. I don’t watch TV. If I do it’s mainly sports or tennis or something like that. I stopped watching the assault—it’s just fear, fear, fear. There’s just love and fear on this planet. Fear got really boring so we watch love and I’m just really grateful that Cindy is in my life now. This is the best part of our lives now.

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

Watch Carlos and Eric Clapton jam in Japan in 2000

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024