During his long and varied career (33 major albums and counting), Elvis Costello has been an enthusiastic chronicler of his songwriting and recording process. His self-analysis fills voluble press interviews, bespoke reissue liner notes and his 2015 memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink. He’s illuminated in detail how his personal life fuels the music, so we know an awful lot about what went into making Imperial Bedroom, his seventh studio album. Enlisting the celebrated engineer-producer Geoff Emerick, who’d worked with the Beatles, the Zombies, Badfinger, Robin Trower and many others, Costello booked George Martin’s AIR Studios in London for 12 weeks. Costello had never planned a session that long before: “The Attractions and I granted ourselves the sort of scope that we imagined The Beatles had enjoyed in the mid-sixties,” he later wrote.

During his long and varied career (33 major albums and counting), Elvis Costello has been an enthusiastic chronicler of his songwriting and recording process. His self-analysis fills voluble press interviews, bespoke reissue liner notes and his 2015 memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink. He’s illuminated in detail how his personal life fuels the music, so we know an awful lot about what went into making Imperial Bedroom, his seventh studio album. Enlisting the celebrated engineer-producer Geoff Emerick, who’d worked with the Beatles, the Zombies, Badfinger, Robin Trower and many others, Costello booked George Martin’s AIR Studios in London for 12 weeks. Costello had never planned a session that long before: “The Attractions and I granted ourselves the sort of scope that we imagined The Beatles had enjoyed in the mid-sixties,” he later wrote.

Emerick was actually doing double duty during the Imperial Bedroom sessions, on occasion engineering Paul McCartney’s Tug of War sessions in an adjacent studio (with Martin himself producing) while AIR’s Jon Jacobs ran the board for Costello. Costello, a stickler for giving credit where it’s due, eventually decided the album credit would read “Produced by Geoff Emerick from an original idea by Elvis Costello, assisted by Jon Jacobs.” “In truth he did nearly everything that could be called ‘production’ in terms of sound, while I concentrated on the music,” Costello subsequently explained.

Imperial Bedroom is generally considered one of Costello’s best albums, with 15 exceptional songs and some of the best work ever committed to tape by the Attractions: keyboardist/arranger Steve Nieve, drummer Pete Thomas and Bruce Thomas [no relation] on bass. Costello, coming off a Nashville foray that yielded his hybrid-country and western album Almost Blue, wanted to record a suite of songs mostly written on piano, under the heavy influence of Billie Holiday, David Ackles, Frank Sinatra and Eric Satie. In addition, he determined the recordings should be “as live as possible,” and started the desired vibe by recording band rehearsals on 8-track tape before the AIR sessions even began. The songs, Costello says, “exhibit a malaise of the spirit and a sinking feeling about happy endings.”

Nearly half the new songs (including “Pidgin English,” “Human Hands,” “The Long Honeymoon,” ‘Kid About It” and “Shabby Doll”) had already been aired live in concert during the latter half of 1981, but Costello was continually playing with tempo, vocal approach and song structure, as rehearsals and sessions revealed new possibilities. He would try out singing higher or lower, adjust the “rant” or “smooth” settings on his versatile voice. Costello greatly admired his band’s expertise, and was willing to follow their lead: Pete Thomas’ improvised drumming on the first stab at “Beyond Belief” led Costello to rewrite the song to bring the lyrics and melody closer to the feel Thomas had captured spontaneously. The song leads off the album with a coiled sense of menace and mysterious lyrics: “History repeats the old conceits/The glib replies, the same defeats/Keep your finger on important issues/With crocodile tears and a pocketful of tissues.”

“Tears Before Bedtime” starts in a weird reggaeish rhythm and blues tempo, with piano and organ lines dueling, and overdubbed multi-Elvis vocals. The bridge is a bit of quasi-Merseybeat pop dropped into a different sonic landscape. Costello says he prefers the alternate version first released on Rhino’s 2002 double-CD reissue, which has a different tempo, melody, feel and lyrics, with no vocal tricks—basically a completely different song with the same title.

“Shabby Doll” begins with a 12-string guitar run through a Leslie speaker, while Costello’s extremely close-mic’d voice ominously intones, “Giving you more of what for/Always worked for me before/Now I’m a shabby doll/What’s going on behind the green elevator door/With just a shabby doll?” With a bang on the drums and a bump on the bass, the band kicks in with a vengeance. Nieve attacks the piano like he’s a mutant blend of Jerry Lee Lewis and Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker. The jagged melody vocal finds echoes from an overdubbed Costello chorus, eventually decaying into echoed howling while Bruce Thomas lays in some bass licks that EC asserts are his best work on the album.

“The Long Honeymoon” is a change of pace, led by Nieve’s accordion and piano, Thomas’ bossa nova drums and Costello’s croon. At one time Costello had tried and failed to enlist the great lyricist Sammy Cahn to compose the song with him: the finished version of “The Long Honeymoon” owes a debt to Cahn anyhow. It’s the tale of a new wife waiting for her possibly unfaithful husband to phone: “She thought too late and spoke too soon/There’s no money-back guarantee on future happiness.”

Costello characterized the LP’s longest cut, “Man Out of Time,” as “a troubling dialogue with myself” and “the heart of the album.” It starts with a faded-in scream, and at mid-tempo seems immediately epic, the lyrics beginning in media res: “So, this is where he came to hide/When he ran from you?” In short order it builds to a soaring chorus, one of Costello’s greatest melodies. All three Attractions are at the top of their game: listen to how Bruce Thomas fits his bass lines over Pete Thomas’ driving drums in the second verse while Nieve puts in power chords right out of a Rachmaninoff piano concerto. The lyrics pummel the protagonist (“He’s got a mind like a sewer/And a heart like a fridge/He stands to be insulted/And he pays for the privilege”) while Costello manages a passionate vocal that recalls both Dylan and Sinatra. At the end the tempo suddenly increases and the opening screams return, leaving the impression that no matter how glib the singer might be he’s still swamped in inarticulate pain. Released as a single, it failed to reach the top 20 in either the United States or Great Britain.

“Almost Blue” and “. . .And In Every Home” finish side one of the LP with a stark contrast. The first is inspired by Chet Baker’s version of “The Thrill is Gone,” and is one of Costello’s most-covered songs. The heartbreaking barroom ballad has a spare arrangement that befits the stark lyrics (“There’s a girl here and she’s almost you…There’s a part of me that’s always true”).

“Almost Blue” (written after the Nashville sessions for the album of that name) not only melodically echoes classics like “My Funny Valentine” and “One For My Baby,” but contains further evidence of EC’s literary and poetic chops, as he keeps hammering the word “almost” from different angles (“It’s almost touching/It will almost do”). He relates a “blue” mood to eyes “red from crying,” and plays with clichés (“Not all good things come to an end,” “Flirting with this disaster became me”). “. . .And In Every Home” is a lushly orchestrated track that is Costello at his most psychedelic. During a break from Tug of War, Martin vetted Nieve’s charts, which contain subtle references to Beatles instrumental scores.

“The Loved Ones,” leading off side two, is a track that wouldn’t be out of place on EC’s Armed Forces album, with one of Costello’s most sneering vocals, along the line of “Oliver’s Army.” Nieve’s piano is dominant beneath, and what he does on the outro is stellar.

“I’ve been talking to the wall and it’s been answering me” is the opening line of the dramatic “Human Hands,” which might be the LP’s strongest overall song and recording. There are echoes of “Watching the Detectives” and “(I Don’t Want to Go to) Chelsea” in the rhythm and arrangement, and the torrent of words is constant, oblique and darkly amusing (“With the kings and queens of the dance hall craze/Checkmate in three moves in your heyday”).

The waltz “Kid About It” is jazzy and loose, and makes good use of Nieve’s organ and EC’s overdubbed vocals. Originally intended to be a slow R&B ballad, Costello pitched it an octave lower “for greater intimacy.” It was written the morning after John Lennon’s murder, when Costello went for a walk to clear his head. He eventually removed an overt reference to the crime, but does mention Liverpool and left the couplet “So what if this is a man’s world/Someone got killed and he cried.”

The Attractions tried “Little Savage” with different moods and tempos before settling into a lighter sort of “Pump It Up” groove. There’s a lot of Stax/Volt in the arrangement; it could fit easily on EC’s Get Happy!!

“Boy With a Problem” is a short ballad written the previous year during the sessions for Trust; it continues the “Almost Blue” vibe with aplomb. The Attractions recorded the beautiful backing track on their own and presented it to Costello “through the letterbox” the next day. “Pidgin English” loads lyrical puzzles into a very Beatles-influenced arrangement by Nieve. There’s a dobro that imitates a sitar, brass and woodwinds and a Spanish guitar solo—a bit too much going on, perhaps.

A harpsichord ushers in the quite delightful “You Little Fool,” which contains hints of the Hollies, the Yardbirds and the Left Banke in its protean melody and the surprising shifts of the arrangement. It’s a show-off cut of immense charm—it even uses an “Itchycoo Park” flange effect as a musical punchline.

Costello calls the concluding “Town Cryer” “a truthful if rather self-pitying lament.” It’s got a lush melody, wildly inventive strings and brass courtesy of Nieve again, and some of EC’s cleverest lyrics, especially his sly American football reference in the repeating “I’m a little down with a lifetime to go.” After he describes himself as “just a little boy in a big man’s shirt” Nieve’s orchestration takes over for a Philly-soul-style coda.

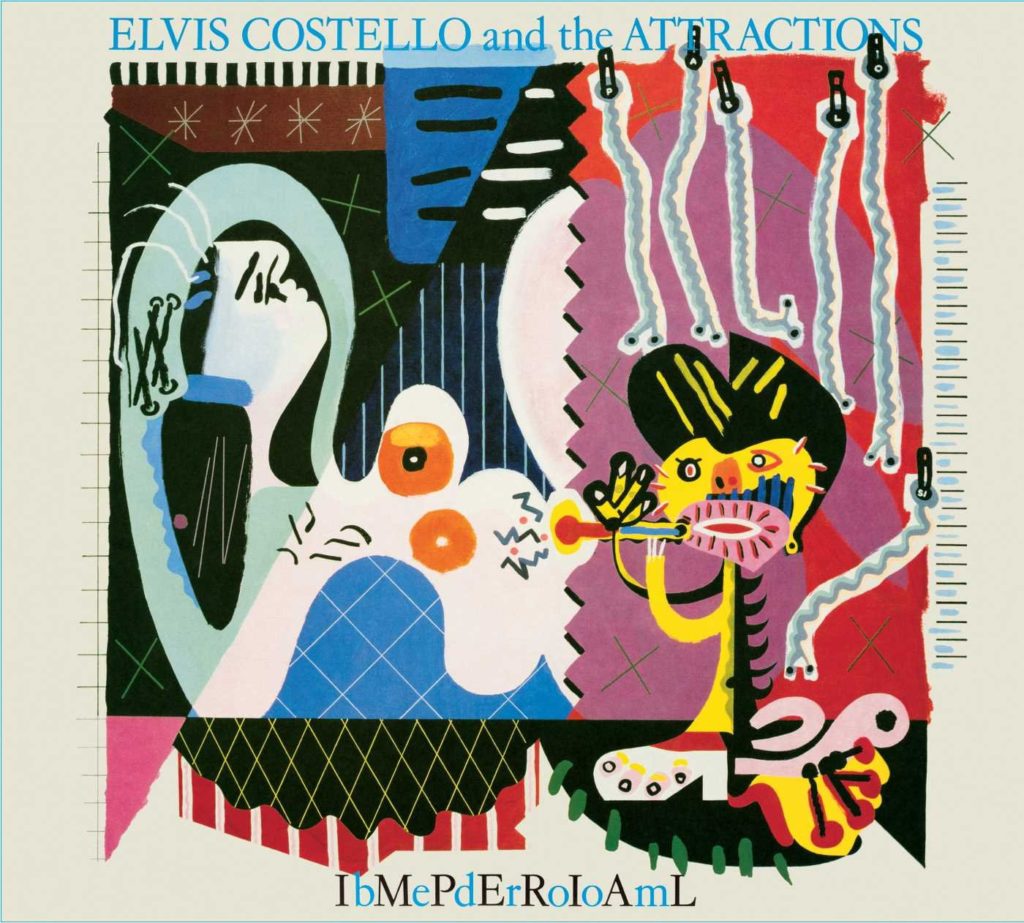

Despite the lack of a hit single, the album, released on July 2, 1982, sold well enough to reach #30 on the American Billboard Pop Albums chart and #6 in the United Kingdom. The witty Picasso-inspired cover art from Barney Bubbles (credited as “Sal Forlenza”) gives a good idea of the multi-colored delights inside. The Rhino expanded reissue is well-worth seeking out; it contains 23 bonus tracks, including fascinating demos, alternate versions, a take of Smokey Robinson’s “From Head to Toe” that was released soon after the album and became a hit single in England, and the title song that didn’t make the album. Costello describes the song “Imperial Bedroom” as “a sick waltz about the seduction of a bride by the best man. It was not a natural choice for the former ABBA singer Frida, but it was nevertheless originally submitted for inclusion on her latest solo album. It was not thought suitable by her producer, a Mr. Collins. He was probably right for once.”

Watch Elvis Costello and the Imposters perform “Almost Blue” live in 2017

Related: Our Album Rewind review of Costello’s Armed Forces

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

2 Comments

Jeez. Incredible break out of one of the world’s absolutely most perfect records — and even saying that doesn’t do it justice. I was gaga over it when it was new, and even now when I play individual cuts, it’s hard to believe how amazingly creative each cut is — A true masterpiece in the most literal sense, and the equal to any of the greatest bands best work.

Mark,

This was as much fun as reading one of Elvis’s extensive liner notes for those Rhino reissues.

My wife and I saw him last night with the Imposters (of course) Nick Lowe and Los Straitjackets.

Elvis did a great version of “Beyond Belief,” but my favorite part of the show was Elvis and Lowe dueting on Lowe’s arrangement of “Indoor Fireworks” and then doing the same on “What’s so Funny (About Peace, Love and Understanding)” during which Lowe added his original “for the children” spoken line part.