According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the most common definition of the word supergroup is “a rock group made up of prominent former members of other rock groups.” The word came into use either in 1968 or 1969, reportedly coined by Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner—music historians seem to disagree exactly when the word first popped up, but they all agree that the supergroup Wenner was describing was Cream.

Cream had already come and gone by the end of 1968 but in their brief run, just over two years, Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker undeniably changed the face of rock music.

In the spring of 1965, guitarist Clapton, having grown dissatisfied with what he perceived to be a move into a more pop-oriented direction for the Yardbirds, the group with which he’d made his name, left for John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. As its name implied, the Mayall outfit was dedicated to the blues, Clapton’s favored genre at the time. Clapton soon grew restless there too, and by the summer of 1966 he was looking for something new.

At the same time, drummer Ginger Baker, a member of the popular British blues band the Graham Bond Organisation, was also in the market for change. When he met Clapton, the two discussed starting a new band and Clapton mentioned bringing in Jack Bruce on bass. Baker was already quite familiar with Bruce—the latter had also worked in Bond’s group as well as with Mayall.

Baker was less than pleased with the suggestion though—the two had not gotten along well when they were in the Bond band and, at its worst, their spats had turned physical. When I interviewed Bruce in 2012, two years before his death, I asked him if his clash with Baker was overblown.

“To a certain extent,” he said. “It did exist but I think those things are in every band, from that time, especially. People now are probably more tolerant of each other. We just didn’t give a shit and we were making it up as we went along.”

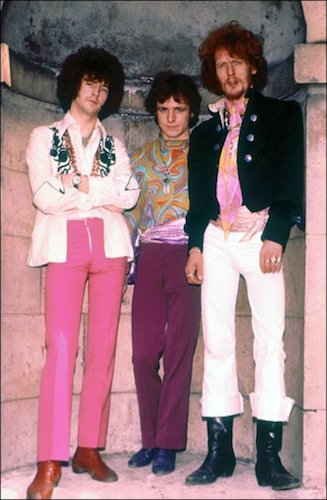

Despite the tension, Cream—as they called their trio, because the three musicians were the “cream of the crop” among British blues-rock musicians—began writing songs and made their live debut at the end of July 1966.

If Clapton was looking for an outlet for his blues fix, he certainly found it in Cream, whose early repertoire included tunes by the likes of Robert Johnson, Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters. Cream took those songs and extended them, adding long improvisatory segments that, to use another phrase popular at the time, blew the minds of fans and fellow musicians.

But right from the start, Cream was more than a blues band. Bruce’s original compositions, especially, tended toward a more eclectic, artsy blend of influences, and—whether Clapton approved or not—there was a decided tendency toward the “heavier,” or psychedelic, brand of mainstream rock emerging that year. Baker, meanwhile, practically invented the concept of the mega-drum solo within rock with “Toad,” a lengthy workout that showcased his prowess on the instrument.

Related: The formation of Cream is announced

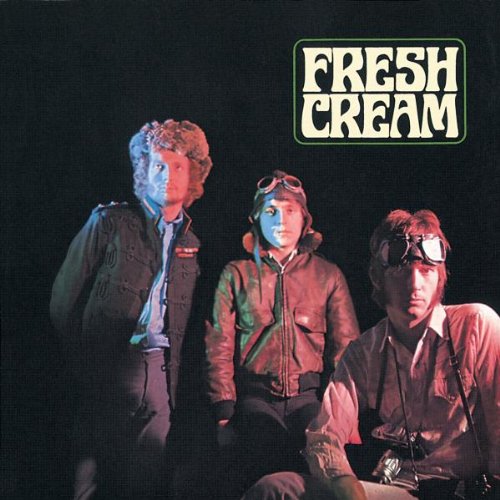

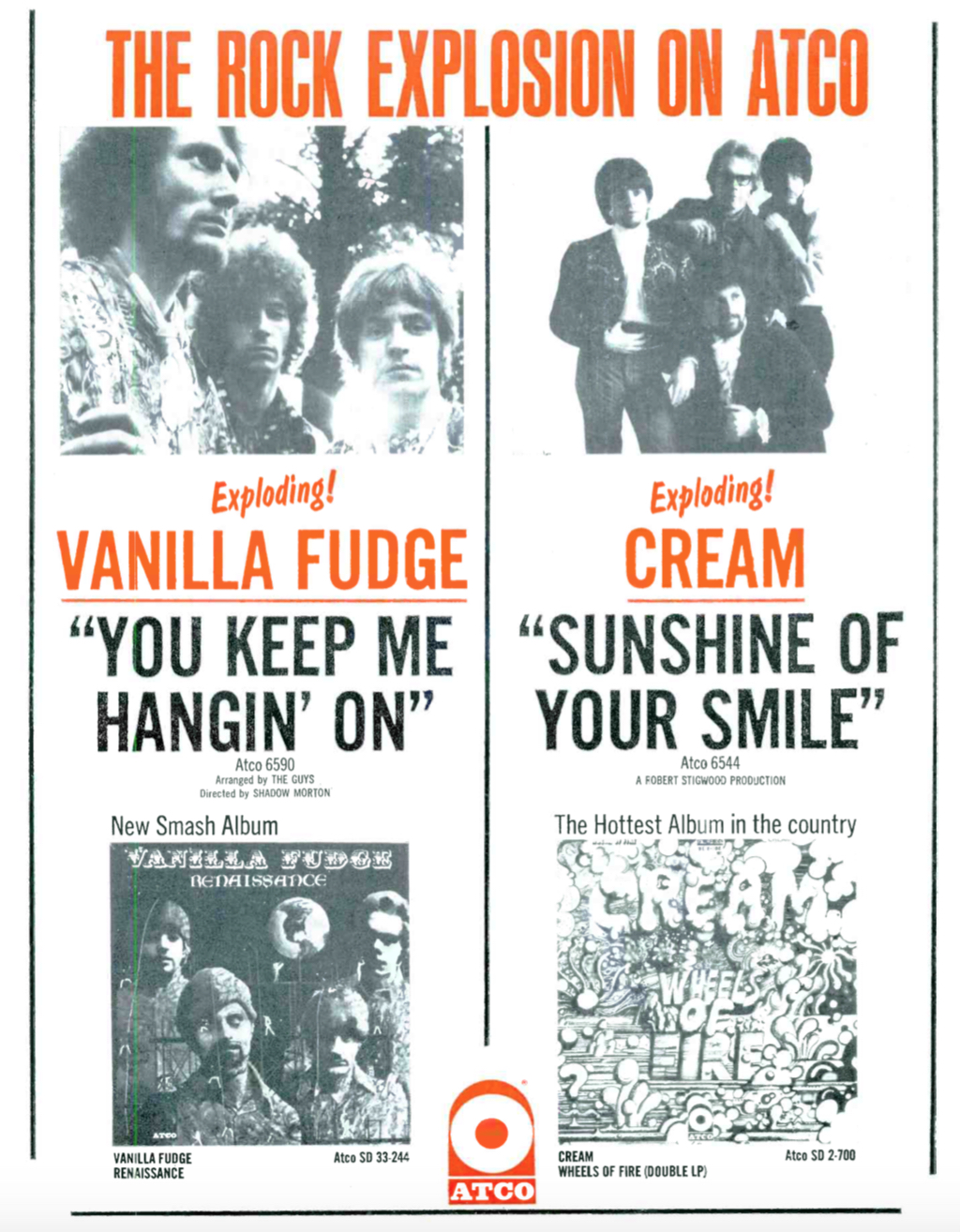

Almost immediately, the group—signed to manager Robert Stigwood’s new Reaction Records in the U.K. and to the Atlantic Records subsidiary Atco in the U.S.—began cutting tracks for what would become their debut album, Fresh Cream. They recorded both blues standards (Johnson’s “Four Until Late,” Dixon’s “Spoonful,” Skip James’ “I’m So Glad,” Waters’ “Rollin’ and Tumblin’”) and originals, mostly by Bruce, including “I Feel Free.”

Stigwood released that side, co-written with lyricist Pete Brown—who would collaborate on later Cream staples, including “Sunshine of Your Love” with Bruce—as a single in U.K., omitting it from the British version of Fresh Cream but placing it as the opening track on the American version (which didn’t include “Spoonful”). The album was filled out with other Bruce tunes, the instrumental “Cat’s Squirrel” and a stripped-down, five-minute version of “Toad,” which ended the album.

Watch the video for Cream’s “I Feel Free” from their debut album

Fresh Cream was released in the U.K. on December 9, 1966, and in the U.S. the following month. The buzz on the band was stronger at home, and the album ultimately peaked on the British album chart at #6. Having not yet performed live in the U.S., and with radio airplay minimal, the Cream LP made it only to #39 in the U.S.

Not to worry though. The year 1967 passed with Cream’s reputation outstripping their record sales, but in early 1968 “Sunshine of Your Love” clicked with the American listener, vaulting to #5 on the Billboard Hot 100. Their sophomore album, Disraeli Gears, released just about a year after the debut, became a massive success, hitting #4 in the U.S. and establishing Cream as one of the most important and influential rock bands of all time.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Disraeli Gears

Just in time for them to break up. Despite the success of Disraeli Gears and its followup, the double LP Wheels of Fire (released in August 1968), Cream was already old news for its three members. Clapton had had enough and was looking for a new direction. Baker agreed, and on July 10 they announced they would be breaking up. They cut one last album, appropriately titled Goodbye, then played their final shows in October and November of ’68.

Clapton and Baker formed a new supergroup, Blind Faith, with former Traffic singer-keyboardist-guitarist Steve Winwood and the relatively unknown bassist Ric Grech, which itself lasted all of one album before falling apart. Bruce continued on as a solo artist and worked in various configurations throughout the rest of his life. Cream was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993 and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006. They reunited for a handful of shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall and New York’s Madison Square Garden in 2005 but, with Bruce and Baker’s rift reignited, all three members—despite the overwhelmingly positive audience response—agreed that was to be the end of it. That thing that was fresh in 1966, for the three people involved, had long ago gone stale.

Watch the reunited Cream perform “Sunshine of Your Love” in 2005

Bruce died on October 25, 2014, at age 71. Baker passed on October 6, 2019, at age 80.

Related: Clapton and Friends played a 2020 tribute concert to Baker

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

8 Comments

Melody Maker were using the term Supergroup in 1966. They had “polls” for readers suggestion for a Supergroup. I think Chris Welch their contributing journalist applied it to Cream in mid-1966, (June?) when writing about them. Not Jan Wenner. Supergroup was in common usage with my friends & I in London before Rolling Stone came out.

Supergroup? That implies that all members are essentially “all stars” — of which Ginger Baker is not. Most overrated drummer of all time.

If you haven’t seen “Beware of Mr. Baker”, seek it out on Netflix or Amazon Prime –

Don’t call Ric Grech “relatively unknown”! He was a founding member of Family and the singer and composer of their “Second Generation Woman.”

Relative to Clapton, Baker and Winwood, he was pretty much unknown.

I thought Yawn Wenner invented Rock and Roll.

Fascinating how even at that point, there was no other paradigm for a music video than basically a copy of George Lester’s frolic-like treatments of The Beatles. While there was superb album cover and sleeve designs with photography and graphic arts, the visual aspects in moving pictures just hadn’t developed that much in the 60s, as an art form.

Clapton has always been an enigma, in the sense that he’s always done his best work when collaborating with others who are talented and challenge him to be his best. Left to his own devices, he’s pretty boring, and has made a lot of vanilla level music. Yet, as much as he seemingly requires the influence of others to stimulate him, he’s never been able either get along with, or tolerate anyone else for very long, in any of his best configurations. Always seems ready to move on before very long.