For a very successful group, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young sure have had a lot of failures. Their on-again-off-again history, coming together and breaking apart in various configurations across five decades, is perhaps the result of too much talent concentrated in four strong personalities. David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young are all consummate songwriters and singers, generating enough material for dozens of solo, duet, trio and quartet albums, but their inability to follow-up 1970’s Déjà vu album in a timely fashion casts a long shadow.

The ambivalence inherent in their love-hate dynamic has been the operating emotional default ever since their spectacular rise in 1969 with their first LP. Young officially joined not long after CSN’s debut became a major hit, but their performance in the Woodstock film only showed three-quarters of the group, as Young refused to be on camera. Crosby, Stills and Nash initially came together because of the extraordinary vocal harmonies they could generate and their openness to collaboration, but as detailed in numerous books, including Dave Zimmer’s 2008 Crosby, Stills & Nash: The Biography, the magic couldn’t be maintained indefinitely.

As 2021’s 50th anniversary boxed set reissue of Déjà vu chronicles, the disruptions of their friendship-rivalry scuttled what could have been a landmark LP called Human Highway. A clutch of brilliant songs, including Crosby’s “Laughing,” Young’s “Birds” and Stills’ “Bluebird Revisited,” were scattered to solo albums or forgotten in tape vaults. Young and Stills subsequently busied themselves with renewed solo careers, while Crosby and Nash joined forces for a tour and the recording of Graham Nash David Crosby, an LP for the Atlantic label that reached #4 in Billboard in 1972. They continued touring as a duo in 1973, and joined a CSNY reunion tour in 1974, but after another failed attempt to record as a quartet, Crosby and Nash signed a new multi-album deal with ABC Records on their own.

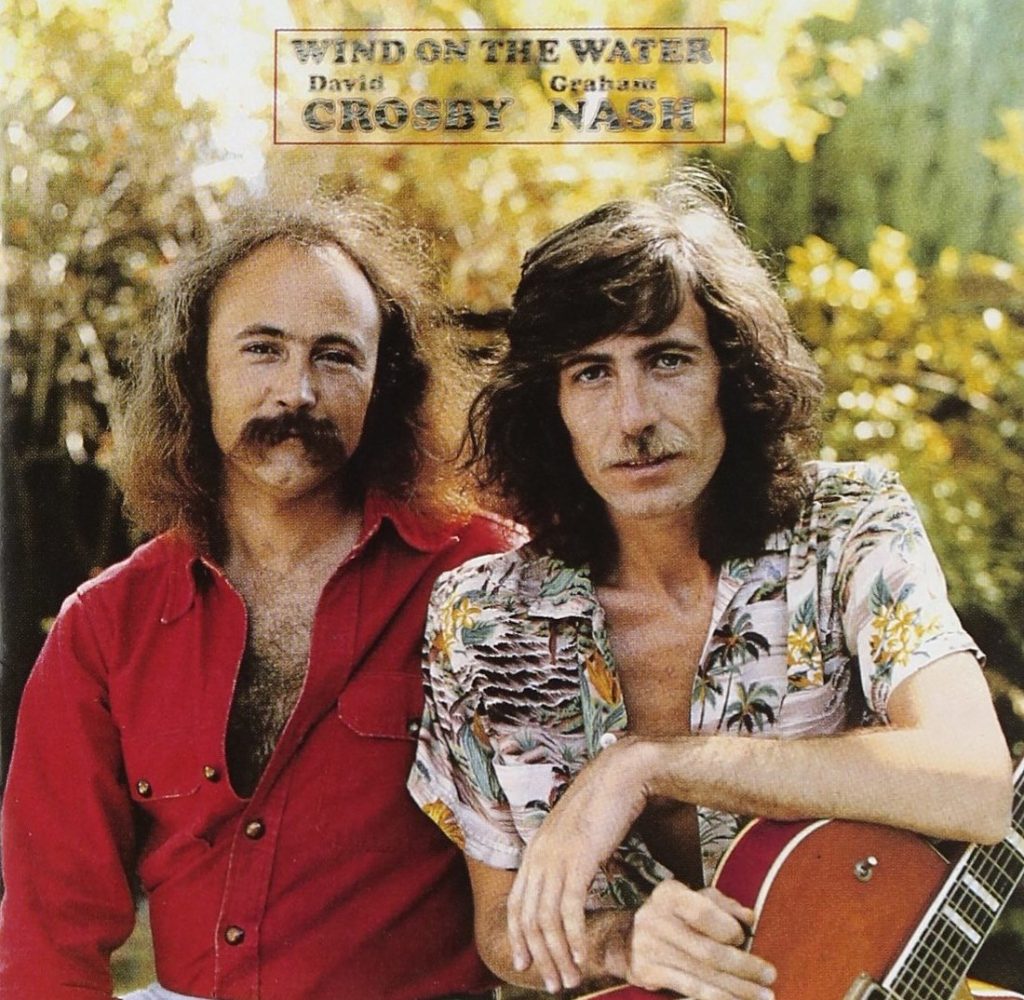

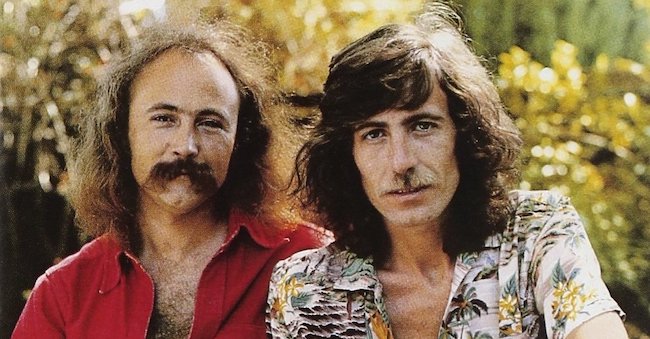

In the spring of 1975 Crosby and Nash were producing their own sessions at Sound Lab and Village Recorders in Los Angeles for what was eventually titled Wind on the Water. Croz told Rolling Stone’s Cameron Crowe he and Nash had intended to make “a pushy record that came right out and collared you.” The expert engineering is by Dan Gooch and Stephen Barncard. Musically, Nash and Crosby were supported by some of L.A.’s best session musicians: drummer Russ Kunkel, bassist Leland Sklar, pianist Craig Doerge and guitarist Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar were known around town as The Section. That core was supplemented by multi-instrumentalist David Lindley (a former member of “world music” pioneers Kaleidoscope), Neil Young associates Tim Drummond and Ben Keith, and backing vocals from friends including Carole King, James Taylor and Jackson Browne. Jimmie Haskell is listed as “arranger and conductor,” handling string arrangements for the title track and consulting overall.

The album leads with Crosby’s “Carry Me,” which he called “a song of transcendence” in an interview with Raymond Foye for a CSN boxed set. The third verse tells the story of Crosby’s mother, dying of cancer in the hospital: “She was lying in white sheets there/And she was waiting to die/She said if you’d just reach underneath this bed/And untie these weights/I could surely fly.” Crosby plays electric six-string and 12-string guitars, with James Taylor on acoustic. The harmony singing is exquisitely pretty, even for such potentially dark subject matter. The song signals this will be an album of emotional weight.

Nash’s “Mama Lion” is at least partly about a visit to his ex-lover Joni Mitchell, on the seashore in British Columbia: “She bounces off the boulders, she runs on the rocks/She’s taking her time from her grandfather clocks.” At the end the narrator admits “there’s a hole in my destiny.” Crosby and Nash sing virtually the whole song in tandem, two men who have been entwined with Mitchell still trying to hash it all out. There are three electric guitars from Nash, Crosby and Kootch, Lindley provides a keening slide guitar solo, and photographer-to-the-stars Joel Bernstein makes one of several LP appearances on acoustic guitar. Kunkel does a wonderfully swinging drum part, with bassist Tim Drummond keeping up.

Crosby’s “Bittersweet” begins with his acoustic piano, his light yet passionate solo voice soon joined by Nash, blossoming into a beautiful, floating melody. Like many Crosby songs it has a unique, non-linear freedom. As “Mama Lion” was guitar-heavy without ever losing its airy quality, this track is full of keyboards, with a subtle interplay of Crosby, Doerge on electric piano and Carole King on organ. At only 2:38, it illustrates the perfection of economy that Nash and Crosby often achieve. Crosby says “Bittersweet” is the result of some noodling on a Wurlitzer keyboard in a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont hotel early one morning. Basic tracks were recorded June 8, 1975, within a few hours of Crosby’s “discovery” of the melody.

“Take the Money and Run” is the first real upbeat track, powered by Kootch and Lindley (on both electric slide and Cajun-style fiddle), with Kunkel/Drummond as the rhythm section once again. For the first time, Nash roughens his voice and shouts the lyrics with palpable anger. It’s his protest against what he saw as the money-grubbing role of certain people during the 1974 CSNY tour: “You cannot give me any more time/You’ve already taken too much of mine/Take the money and run.”

“Naked in the Rain” is based on an LSD trip Crosby experienced with the songwriter Dino Valenti. In a North Beach, San Francisco, hotel he hallucinated “fluttering pages of faces, no two alike.” Crosby wrote the melody but Nash helped finish the lyrics, making it the only co-write on the album. At just a bit over two minutes, it’s a non-repeating fragment, very typical of Crosby’s unorthodox style. Crosby is fearless in showing his deepest emotions in song, and “Naked in the Rain” is a great example: “When it dawns on you/What it takes from you/Living under clouds of pain/There’s a storm in you/You don’t know what to do/Just when you think you’re going insane/You lie naked in the rain again.” The melody has hints of Crosby’s masterful songs “Triad” and “Déjà vu.” The interplay of guitars, and Doerge’s electric piano is worthy of special attention.

Nash’s “Love Work Out” finishes the first LP side with a stomping arrangement, dueling “Warpath guitars” from Crosby and Kootch, prominent organ by Doerge, more incredible Lindley slide work, and nice vocal help from Jackson Browne. Once again, Nash shows his anger, especially in the chorus: “I used to keep on trying from day to day/To keep from dying and fading away/It seems like a strange thing for me to say/I’m so tired of looking back the other way/So love work out.” Maybe he had this kind of song in mind when he once told People magazine, “I vacillate between being in love and being totally pissed off. There’s very little in between for me.”

Crosby’s “Low Down Payment” leads off the second side, an exercise in tempo and tone changes that wanders around a bit too much, for nearly five minutes. The lyrics flirt with the line between poetry and gibberish: “It’s a low down payment on this pillar of salt/It’s only had one owner, and he up and died/He died of guilt/And you can drive it out of here/All you do is find a gear/That will not blow it apart.” Kootch lays down a very rocking solo at the end.

“Cowboy of Dreams” is a waltz with lyrics based on a visit to Young’s ranch, and the gift of two black swans that were killed by predators. Written by Nash, it sounds like a forgettable Eagles outtake, with Lindley’s fiddle-playing the highlight. “Homeward Through the Haze” leads with Carole King’s acoustic and Doerge’s electric piano, and bears the imprint of Crosby’s favorite band Steely Dan in its light swing and meticulous band arrangement. Kunkel does some lovely fills, Kootch solos with authority, and the moments when Nash, Crosby and King vocalize together are some kind of wonderful.

“Fieldworker” is another Nash protest song, sparked by his attending a sumptuous party at David Geffen’s house in L.A. and then driving to meet with farmworkers in Delano later that day. The lyrics are blunt as he puts himself in the shoes of a migrant worker: “I came across your border just to work for you/I give you all I got to give/What more can I do?/Don’t give me law and order/Tell me to stick around/While standing in the picket line/You try and shoot me down.” Musically, Ben Keith’s electric slide guitar commands attention from the start, and Kunkel steps aside to play some percussion while Levon Helm handles the drumkit. Nash’s lead and the overdubbed harmony vocals can’t be faulted, but the band doesn’t seem to be able to inject such a by-the-numbers song with much energy.

The five-and-a-half-minute, two-part “To the Last Whale” consists of Crosby’s “Critical Mass” and Nash’s “Wind on the Water.” Crosby’s wordless vocal for “Critical Mass” had actually been recorded in September 1970 for a different project, while Nash’s was tracked to blend in during a December 1974 session in Los Angeles. Crosby says it was influenced by listening to his mother’s classical music collection, especially Bach (ergo the pun in the title).

“Wind on the Water” was inspired by a nine-week sailing trip, and the thrill of seeing a blue whale from the deck of Crosby’s schooner The Mayan: “It’s a shame you have to die/To put the shadow on our eye.” Basic tracks were done April 13, 1975, at Village Recorders, with additional recording for string orchestra and more at Sound Lab. James Taylor plays acoustic guitar and sings, and the combination of Doerge’s electric piano and Nash’s acoustic piano pays dividends. As the album ends, is Nash referring to marine or human life when he sings, “Maybe we’ll go/Maybe we’ll disappear/It’s not that we don’t know/It’s just that we don’t want to care”? It’s one of Nash’s most enduring songs, and earns its position as title song.

Released Sept. 15, 1975, Wind on the Water from Crosby and Nash made it to #6 on the Billboard Hot 200. (In an unusual move, the vinyl LP was marketed by ABC and Atlantic handled the cassette and 8-track versions.) Although it achieved “gold” status upon release, since then it’s gone in and out of print; a 2008 U.K. CD reissue with a bonus disc containing a San Francisco live show is nearly impossible to find.

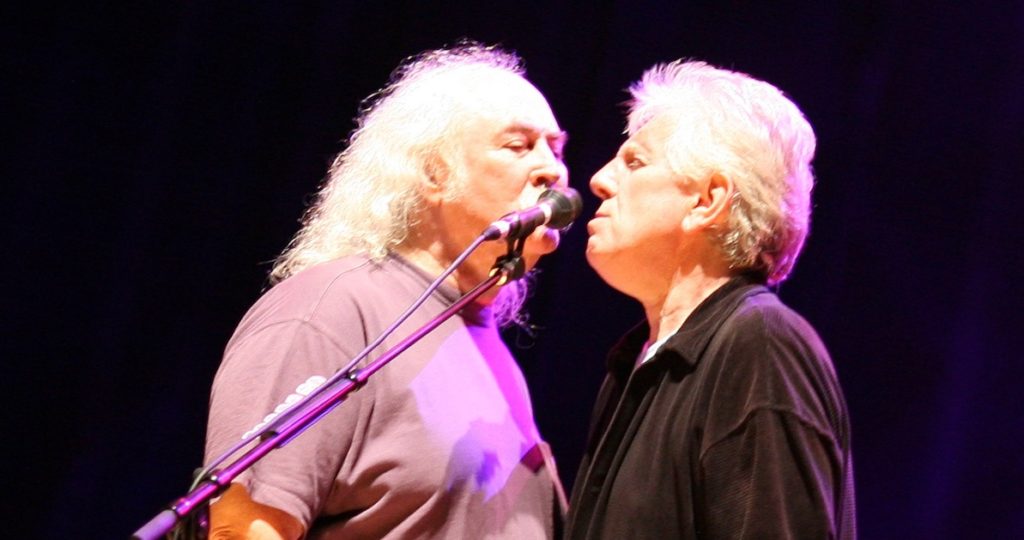

Crosby and Nash continued to release new music well into the 2020s. In recent years, they carried on a bitter feud in music magazines and on Twitter. Promoting the Déjà vu boxed set, Crosby said, “I don’t expect to be friends with Graham at any point. Neil hates my guts.” Nash explained, “When that silver thread that connects a band gets broken, it’s very difficult to glue the ends together. It doesn’t quite work. And so, things that happened in me and David’s life broke that silver thread, and for the life of me, I can’t put it back together. I do wish I could, only because of the loss of the music.” Amen to that.

Related: We arranged for Crosby to give a 2022 interview… to a high school journalism class

Bonus Audio: Listen to Crosby, Stills & Nash sing “To the Last Whale” live in 1989

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

4 Comments

Crosby and Nash made some great music together. Some of my favorite albums in my collection. Thanks for having this to read and great job writing about them.

So many great musicians and very good material. I had it when it came out. Great write up. Makes me want to dig out my LP and have a listen.

David Crosby is genius musically. I have listened to the CSN band since I was a teen back in 69, and then CSNY. I always wanted to say thank you for gifting us your talents.

Would like whatever can occur for CROSBY STILLS and NASH to heal their relationship and sing together again…Mr. Crosby has spoken of his health issues, and I worry re him….y’all were friends in past, loved each other in past and should any of y’all die, I believe regret will ensue…