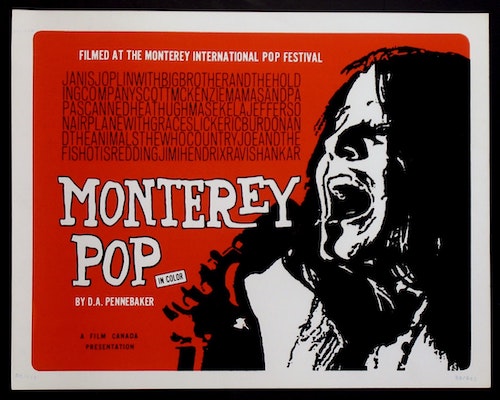

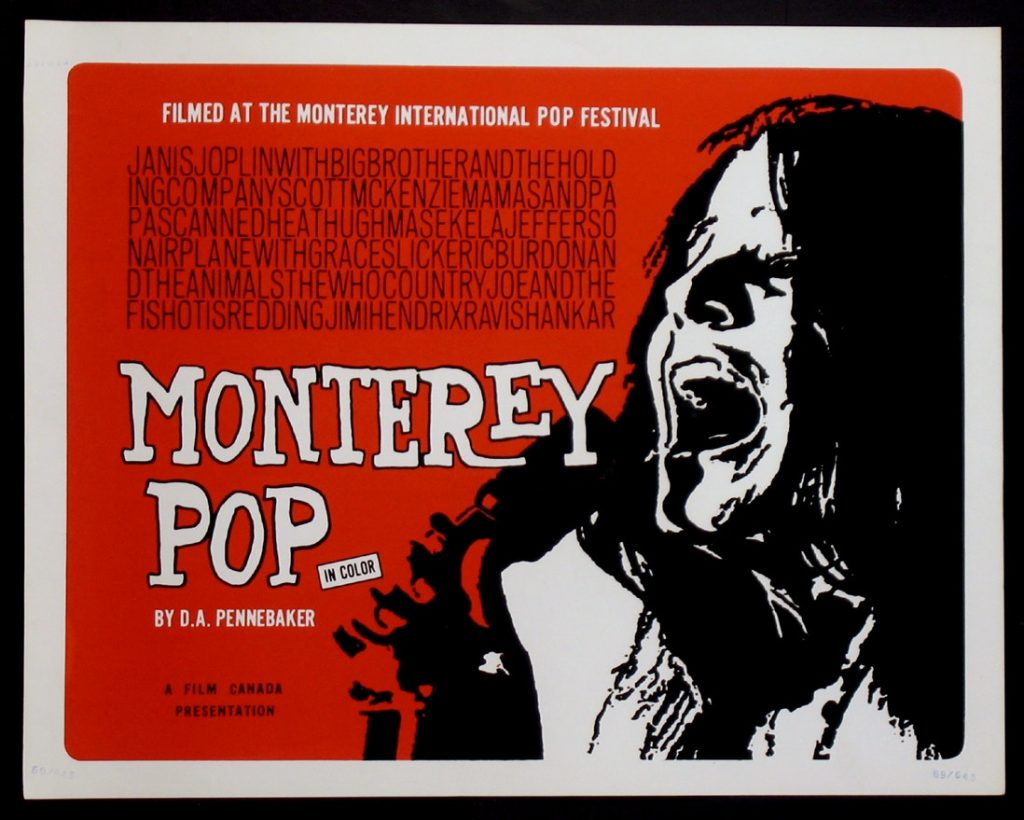

The renowned documentarian D.A. Pennebaker passed away on Aug. 1, 2019, at the age of 94. Nearly two decades earlier, he sat down with Best Classic Bands’ editor to discuss some of his most famous films, including Monterey Pop, the 1965 Bob Dylan documentary Dont Look Back, the David Bowie vehicle Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and others. Joining Pennebaker (born July 15, 1925) for the chat was his creative partner and wife, Chris Hegedus. Almost none of the interview was published prior to his death in 2019.

Best Classic Bands: One of the highlights of Monterey Pop was Jimi Hendrix’s performance of “Wild Thing,” during which he famously lit his guitar on fire. When you look back at that footage, what comes to mind?

D.A. Pennebaker: He was a flash of lightning on a dark rainy night. That’s all I can tell you. He lit up the sky. What he did was so seminal, so completely personally delivered, I think it’s unique.

Chris Hegedus: I think that many amazing musicians show their genius by lasting through different generations. You see it with somebody like Bob Dylan, who seems to have a whole younger base group of fans now. Jimi musically crossed over to so many different styles; the range of people that he spoke to was enormous. He never has fallen out with any young group of musicians that comes along.

Watch Hendrix sacrifice his guitar at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival

BCB: Many rock fans got their first exposure to Hendrix from Monterey Pop.

DAP: It certainly was for me.

BCB: When he took out the lighter fluid and started burning his guitar, were you thinking, “Quick, save my cameras”?

DAP: I didn’t feel there was that much danger. I felt that the Who [who trashed their instruments at the close of their set] represented a greater camera risk. John Phillips [of the Mamas and the Papas] had sort of told me before the show, “Listen, there’s this one guy and you gotta film him. He sets himself on fire.” And I thought, what kind of a blues thing is that? I can’t imagine John Lee Hooker setting himself on fire, no matter how upset he got. So I was sort of intrigued. Luckily, everybody just kept shooting for the whole thing, so we had that whole set. But it was such an astounding thing. I didn’t know what to make of it. I tell you, I was blown away.

BCB: Was there a sense from the start that this was a historic moment?

DAP: We had that several times. We sort of felt that the whole thing had a historical quality, at least I did.

Watch the Who play “My Generation” at Monterey

BCB: Janis Joplin’s Monterey appearance is a whole other story. You initially were not allowed to film her.

DAP: We couldn’t shoot her because her manager [Albert Grossman] was a shithead. But then she came back and performed again, and I thought, boy, everybody realizes this is special.

Watch Janis at Monterey

BCB: The Grateful Dead also didn’t allow you to film them.

DAP: No, we filmed the Grateful Dead, but we didn’t do it very well, because they played for like 45 minutes. Everybody ran out of film halfway through it! [laughs] Grateful Dead music does not translate well into a film which is comprised of a lot of different kinds of music. It’s too all-consuming. You tend to sit and listen to that and you fall into a reverie.

BCB: Was it always your plan to end the film with Ravi Shankar?

DAP: Pretty much, yeah. I thought, how can I get people who’ve never heard it before, who don’t even know what a sitar is, to sit and listen to a half-hour raga? I thought that would be the problem in the film. [My idea was] to lead them down there and then hit them with that and they’ll really have gone someplace.

BCB: One more Monterey question. When you filmed Jefferson Airplane’s ballad “Today,” the lead singer on the song is Marty Balin but the camera stays on Grace Slick’s face the entire time he’s singing. What was the reason you didn’t show Marty?

BCB: One more Monterey question. When you filmed Jefferson Airplane’s ballad “Today,” the lead singer on the song is Marty Balin but the camera stays on Grace Slick’s face the entire time he’s singing. What was the reason you didn’t show Marty?

DAP: Well, the thing there was, it was a dumb problem and we didn’t know it until we sent the film up [to be processed]: there was no mic on her and the only lighting was not on him, but on her. They corrected it halfway through the song, but at the time we thought, it’s kind of psychedelic, right? We thought we could get by on psychedelic. A lot of people thought it was such a great idea. They said, “Boy was that a smart idea.” So I always took credit for it for as long as I could.

Watch the Airplane’s “Today” from Monterey Pop

BCB: Let’s talk about Dont Look Back. Was Dylan cooperative?

DAP: Oh, yeah. He was adorable.

BCB: Would you say he was playing to the camera?

DAP: No more than he plays to people. He likes to play to people. He’s a performer who likes a very small audience and likes to invent himself, as he goes along. That, to me, is the kind of person you need to make these movies. You’ve got to understand that I’m standing there, usually I’m all alone, I don’t even have a sound person around. I’ve got a tape recorder that I put on the floor or kind of have on my side. I think he didn’t see the camera so much. A couple times I can see he’s looking right at it and laughing. But he saw it like you would on a home movie, when the guy at the picnic was drunk and taking pictures. It’s part of the action. It’s nothing you’re supposed to not look at. And I kind of dug that. He kind of rebuffs people, because he’s such a survivor.

Watch the scene from Dont Look Back when Dylan meets Donovan

BCB: You did a second film with Dylan the following year, called Eat the Document, but it never came out officially. The story I’ve heard is that Dylan decided to edit it himself but it was never quite finished.

DAP: Well, it’s been through a few sea changes. Originally it was going to be Dylan’s film. That was the deal, and I was going to help him make it. I was going to run the camera but he was going to direct it and kind of figure out what to do. He didn’t want to make Dont Look Back again. That was the understanding, that it was his call. It wasn’t for me to say. But the only thing I could shoot was Dont Look Back again. I didn’t know how to shoot any other kind of movie. So, it wasn’t turning out exactly like anybody thought, but he couldn’t control it. Because directing a film is not having film ideas, it’s marching a battalion of people around, telling them what to do and making them do it. That wasn’t something he could do very well. He had people do that for him. So when it got finished, there was a film there, there were some fantastic performances there, but when we started to put that together with him he started to have second thoughts. So finally, I moved a couple of editing machines up to Bearsville [New York] and threw all the footage at him because we were supposed to do it for an ABC show. And Albert [Grossman, who managed Dylan as well as Joplin] was on my back, saying “Where’s the film? I don’t care what Dylan thinks. We’ve got to deliver a film or we’re going to lose some money. Get going on it!” We were sort of editing something in New York, and he was doing something up there. And then I finally just said, “This is ridiculous. If you want to have him do it, you’ve got to make him do it.” I don’t know who did what, but it’s a peculiar film. I think it loses a lot of what I know was there in the concerts. The rest of it kind of doesn’t matter, it’s all… style.

Watch a scene from Eat the Document featuring Dylan and John Lennon conversing in the back seat of a car

BCB: Switching gears, let’s talk about Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust film. What attracted you to making a documentary of his 1973 tour, which was supposed to be his farewell?

DAP: Well, he is incredible to watch. I mean, I could see myself getting a hard-on just looking at him sometimes, which is ridiculous. But I think that the reason we made it was because RCA Records said, “We have this guy and he’s going to do a concert, maybe the last one he’s going to do, and you’ve got to go make a film.” I thought they said Bolan—I thought it was Marc Bolan I was going to do! And I was very excited because I really dug glitter rock. So I kind of set off with the wrong guy in mind. We got there the day before the concert. We had very little time to spend with him. I saw one concert that night, and just looked at it to see what the lighting should be, and listen to it, and got totally entranced by it. And then the next night we shot it. I spent some time with him, backstage but, you know, he’s a businessman. He didn’t have that peculiar spiritual thing that Dylan conferred when you filmed him.

Watch the trailer from Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

[The fully restored film and soundtrack will be released for the first time for the 50th anniversary of the show on 2-CD & Blu-Ray, 2-CDs, and 2-LPs, on Aug. 11, 2023, via Rhino/Parlophone. The 4K digital restoration of the new version of the film has been overseen by the filmmaker’s son, Frazer Pennebaker, with remastered audio.]

BCB: You also made a film with Depeche Mode, 101. Why them?

DAP: They came to us and said, “Would you like to do a film of Depeche Mode?” And we said, “Who’s Depeche Mode?” That’s OK. You don’t have to know everything. So it was neat. We loved doing that film. We spent time with them and we got to be good friends with them.

BCB: How do you choose your subjects? They’re so diverse.

DAP: Generally, people bring them to us, and then we try to raise money. And if it’s hard to raise money that’s news right there. That tells you you’re on the wrong track. Sometimes you decide to do it anyway. Fuck ’em.

BCB: Would you make a film on somebody you didn’t care for?

CH: I think the closest we came to that was when we did a film on [automobile magnate] John DeLorean. He’s kind of like a Disney villain. He was likable, but you kind of knew that there was something going on there. [Editor: DeLorean was charged with cocaine trafficking in 1982.].

BCB: When you made The War Room, about Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign, did you find yourself getting caught up in the drama?

DAP: Well, sure! You’re ready to vote as many times as you can get into the voting booth, because so much seems to depend on it.

CH: Everybody really was so taken with Clinton at the time. It was a very idealistic period. The Democrats hadn’t been in the White House for a long time, and everybody had a lot of hope and that’s very infectious.

BCB: What attracted you both to the documentary medium in the first place?

CH: I kind of got attracted to it because I came from an art background and I saw them as films that you could kind of do yourself, like art.

DAP: In those days, suddenly people were figuring out how to make these movies, which up to then had to made in big factories in California or made by special cameramen in wars and things. I suddenly thought, God, this is possible. This is something you could do. I was naïve about the business; I thought I could make a five-minute film and sell it to somebody.

BCB: Which of your films do you think people will still be watching a hundred years from now.

DAP: Well, now, which of my children do I want to behead? Which am I going to let live? I don’t know.

Watch the 42-minute Sweet Toronto, featuring John Lennon and Yoko Ono with the Plastic Ono Band, plus Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, an electrifying Little Richard, and more

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024