David Crosby’s musical journey is a tale rife with contradictions. There’s the obvious brilliance he first shared while with the Byrds and then, later, his contributions to America’s first true supergroup, Crosby, Stills, Nash and (at times) Young. By having a hand in the writing of songs that helped define both bands—among them, such enduring classics as “Lady Friend,” “Why” and “Eight Miles High” for the former, and “Guinnevere,” “Wooden Ships,” “Almost Cut My Hair” and “Déjà Vu” for the latter—he played a major role in establishing a timeless template that reflected a freedom-first attitude of the ’60s that resonates even today. Likewise, his rich tenor and unmistakable jazz-like sensibilities imbued each group with a firm foundation for their exacting vocal harmonies. Crosby also helped establish a free-flowing communal kind of creativity, another distinctive element that led to a more synchronous sound.

David Crosby’s musical journey is a tale rife with contradictions. There’s the obvious brilliance he first shared while with the Byrds and then, later, his contributions to America’s first true supergroup, Crosby, Stills, Nash and (at times) Young. By having a hand in the writing of songs that helped define both bands—among them, such enduring classics as “Lady Friend,” “Why” and “Eight Miles High” for the former, and “Guinnevere,” “Wooden Ships,” “Almost Cut My Hair” and “Déjà Vu” for the latter—he played a major role in establishing a timeless template that reflected a freedom-first attitude of the ’60s that resonates even today. Likewise, his rich tenor and unmistakable jazz-like sensibilities imbued each group with a firm foundation for their exacting vocal harmonies. Crosby also helped establish a free-flowing communal kind of creativity, another distinctive element that led to a more synchronous sound.

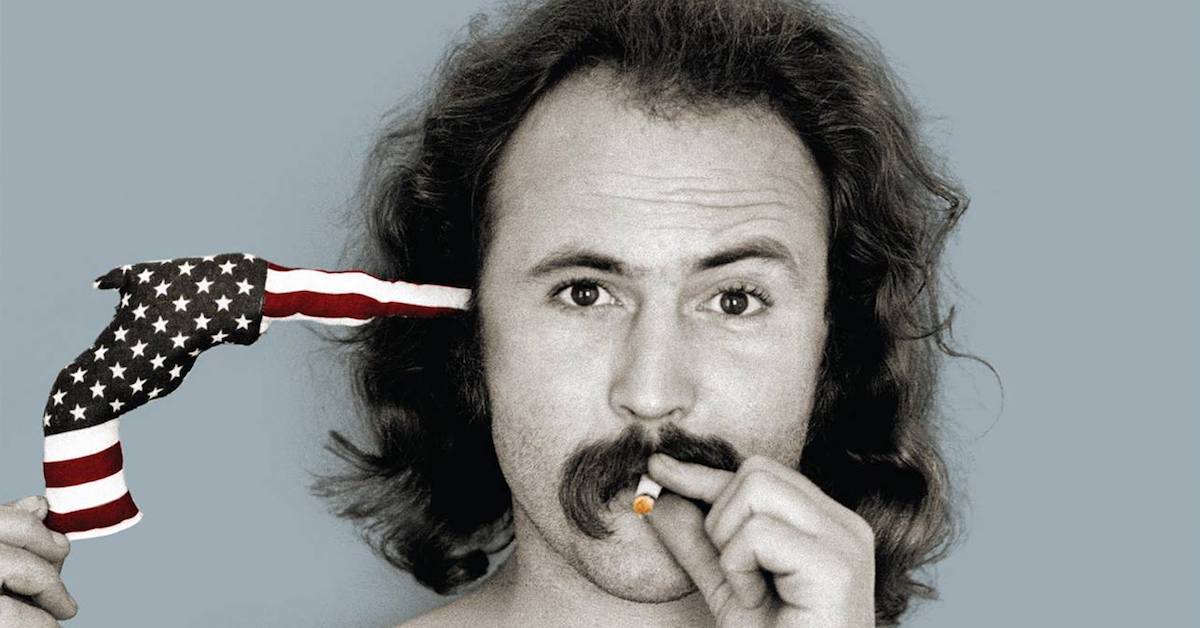

At the same time, Crosby’s tendency toward self-destruction and an anarchistic attitude often threatened to undermine those efforts, giving him the reputation of a perennial troublemaker who had to be dealt with in order for each group to ensure its own survival. Crosby and chief Byrd watcher Roger McGuinn clashed when Crosby insisted the group record his ode to hedonism, “Triad,” a song that celebrated the joys of a ménage à trois (the Byrds did record it but didn’t release it at the time; Jefferson Airplane happily included it on one of their albums). During 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival, Crosby broke ranks with a rant about a Kennedy assassination coverup, after which he famously took the stage with Buffalo Springfield, filling in for an absent Neil Young. Within months he was fired by the Byrds’ two remaining original members, McGuinn and Chris Hillman. His drug habit later got the best of him, creating added tension within the CSN and CSNY dual dynamic while short-circuiting his own prolific prowess at the same time.

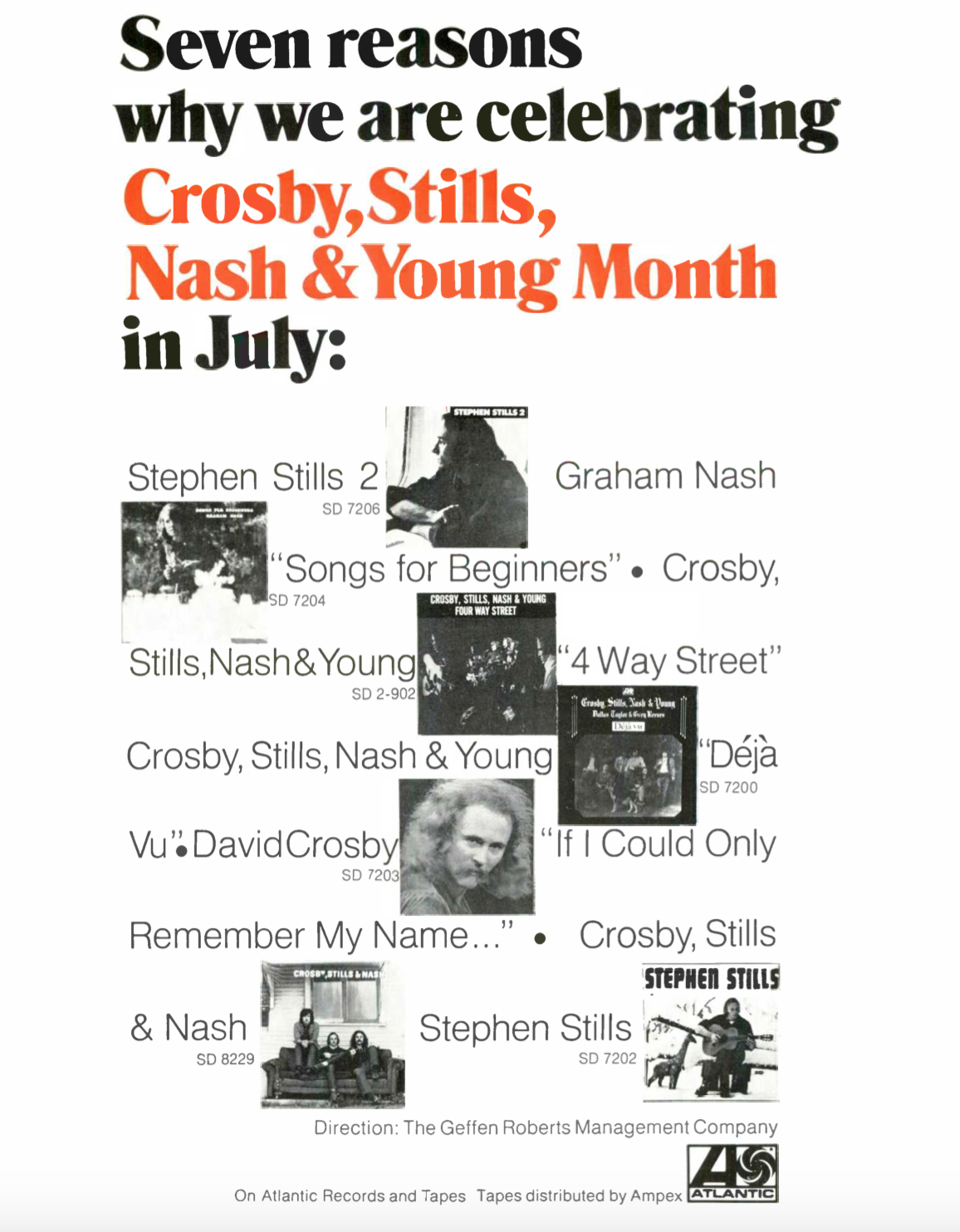

Given the personality clashes and eternal discord that frequently rocked those partnerships so early on, it was little surprise that the quartet failed to follow up its well-received debut Déjà vu with anything other than 1971’s live album, 4 Way Street. Indeed, it would be another six years before the seminal trio was able to muster another album with the eponymous CSN. However, none of the individuals involved settled for silence.

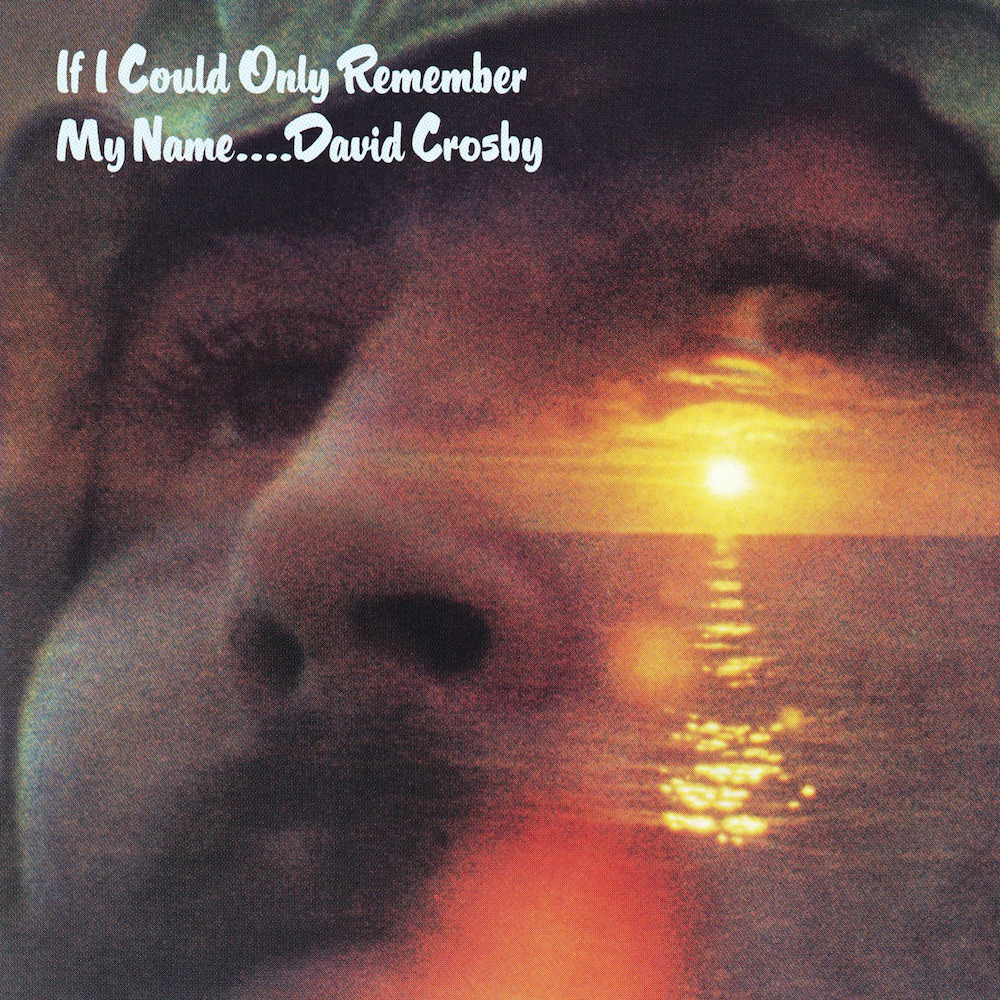

Each went off to their individual corners and released albums of their own—Neil Young with After the Gold Rush, Stephen Stills with his self-titled solo debut, Graham Nash offering Songs for Beginners and Crosby sharing his own initial offering, an eerily ethereal set of songs dubbed If I Could Only Remember My Name. Indeed, the title of the latter appeared somewhat self-effacing, alluding to Crosby’s renegade reputation as a confirmed druggie with only the most tenuous grip on reality and/or responsibility.

Related: Our review of the Crosby documentary, Remember My Name

Little may have been expected of him at the time, given that some believed he wasn’t capable of sustaining himself without the tethers of a band to properly support him. Indeed, it would be another 18 years until the release of a strictly individual followup, 1989’s prophetically titled Oh Yes I Can. However, no one needed to have worried in the interim. Crosby gathered a superb supporting cast, one that featured the communal contributions of friends and fellow travelers, among them, members of the Grateful Dead (Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart), Jefferson Airplane (Grace Slick, Paul Kantner. Jorma Kaukonen, Jack Casady), Santana (Gregg Rolie and Michael Shrieve) and Quicksilver Messenger Service (David Freiberg), along with faithful standbys Graham Nash, Neil Young and Joni Mitchell.

Not surprisingly, many of the musicians would later reprise their roles within Kantner and Slick’s initial incarnation of Jefferson Starship—the serendipitously dubbed Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra (PERRO)—and contribute to their fanciful debut Blows Against the Empire. (Crosby cowrote its signature song “Have You Seen the Stars Tonite” with its helmsman Kantner.)

After converging on Wally Heider’s Bay Area studio, the group’s collaborative efforts resulted in a series of songs that often emerged more like free-flowing jams and seemingly spontaneous collaborations, as opposed to anything with concise song structure.

That was manifest in the hazy drift and dream-like designs of “Tamalpais High (At About 3)” and the self-described instrumental “Song With No Words (Tree With No Leaves),” the mellow and meandering “Laughing,” the chant and incantations that stirred the hippie sentiments of “Music Is Love,” and the seemingly paranoid suggestion inherent in the song “What Are Their Names?” and the quiet contemplative ode to his deceased lost love Christine Hinton with “I Swear There Was Somebody Here.”

(Note: an outtake from the sessions, “Kids and Dogs,” later included on Crosby’s Voyage anthology, would also have found a fit within that surreal setting.)

In truth, the album’s success owes much to its somewhat vague atmospheric ambiance. The material seems to float along with serenity and serendipity—all loose, lethargic and driven by hazy dayglo designs. Not surprisingly, the sound seemed to retrace earlier efforts such as “Guinnevere” and “Déjà Vu,” both in terms of themes and structure. Yet, while Crosby was credited as producer, it was also clear that each of the participants also played their part when it came to structuring the proceedings. Indeed, it was as much a credit to the ability of those involved to simply go with the flow as it was to Crosby’s attempts to create some coherence.

Related: Our Album Rewind of CSN&Y’s Déjà Vu

“Cross-pollination will make the whole musical world better,” Crosby was quoted as saying at the time. “The more we work with each other, the less we isolate ourselves, the less we try and get into group roles, the less we try and be cliquish and hang out only with our little buddies, the stronger the music’s going to be.”

Engineer Stephen Barncard had his reservations when he was assigned to do the record, referring to Crosby’s reputation as being that of an “asshole.” However in Crosby’s autobiography Long Time Gone, he describes the recording, which began in November 1970, as “the most exhilarating project I’ve ever done in my life…It was a loose setup…but I learned to relax with it and before we knew it we were ready to mix.”

Released on February 22, 1971, the album evoked the anything-goes attitude that was so prevalent during the sunset of the ’60s just prior to the hard political realities that were encroaching on the early ’70s. Although it received mixed reviews at the time and fell just shy of Billboard’s Top 10—a somewhat disappointing placement considering the success attained by his colleagues—it’s been reevaluated given the passage of time, and now rightfully regarded as one of the hallmarks of Crosby’s nearly 60-year career.

That in itself is an accomplishment well worth remembering. [The album received an expanded edition in 2021 to mark its 50th anniversary and is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Bonus Video: Watch Crosby and Graham Nash perform the album’s “Traction in the Rain” live on the BBC

Crosby’s vast catalog is available here.

Related: Our obituary of Croz, who died in 2023

9 Comments

Fantastic album. I listened to it reputedly over the years, even as the critics especially Rolling Stone condemned it. It was the birth of a New Sound. Interestingly his recent work beginning with Croz is every bit as good if not belter. He’s having a fantastic Sunset Career. Stunning to behold, as he works with those marvelous young musicians, including his son.

Cowboy Movie was about the break-up of CSNY

You nailed it. One of the finest L.A. hippie albums, one that rewards virtually endless replays.

I dig the album as well but I always have seen it as a Norcal hippie album. Not that it matters

Always loved it. One of my personal favorite albums.

For as messed as he was his use of chords and harmonies can’t be equaled even by todays standards .

Back in the days of LPs, when it was released, it hit the cutout bins pretty fast, especially considering who the artist was, and the people who played on it. But I always felt that it’s quick trip to discount land had more to do with the record company’s belief in it, and willingness to promote it, than anything else. As is alluded to here, it is a different kind of record, but more importantly, it’s an amazing amalgam of renowned California musicians who, seemingly, blended together seamlessly with Crosby’s dreamy song ideas. Upon first listen, you can tell it’s a one-of-a-kind-record, that’s kind of like a sonic dream. I’ve always loved it, and it continues to be a treat whenever I’ve played it over the years. As much as I’ve heard Crosby’s later recordings are as good or better, I’ve always been kind of reticent to dive in, thinking they could never be as good as this one. But I guess I really do need give some a try.

I grew up listening to Byrds music, started, as I have written before, hearing my cousins play 1st Byrds record, then 2nd and third! Byrds albums were key albums for me, loved every one! Byrds box set was 1st box set I bought!

This is one of Crosby is one of my all-time favorite albums…every track! I listen often and love his voice [and his politics!]. This album was done around time, when his girlfriend died, and all his friends comforted him doing this album….he had the most amazing voice and his dreamy ‘tunes’ are so beautiful to me…Orleans indeed! I was saddened by his passing and yet he lives for me when I play his music…

Nice article. Great album. Look for the PERRO Sessions in all the grey area markets for addition recordings/outtakes from the sessions, I’ve seen differing collections out there with different tracks. The sessions are well documented on the internet so you crate diggers can learn even more