After the commercial and artistic triumph of their 1972 studio album Machine Head, the hard rock band Deep Purple found themselves under pressure from two record labels to follow it up, pronto. Singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, drummer Ian Paice, keyboardist Jon Lord and bassist Roger Glover (nowadays commonly referred to as Deep Purple Mark II in the rock annals) were signed to Warner Bros. Records for the United States, Canada and Japan, and to EMI for the rest of the world; both big companies knew momentum—or the lack of it— could determine whether a band had a robust career or not.

After the commercial and artistic triumph of their 1972 studio album Machine Head, the hard rock band Deep Purple found themselves under pressure from two record labels to follow it up, pronto. Singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, drummer Ian Paice, keyboardist Jon Lord and bassist Roger Glover (nowadays commonly referred to as Deep Purple Mark II in the rock annals) were signed to Warner Bros. Records for the United States, Canada and Japan, and to EMI for the rest of the world; both big companies knew momentum—or the lack of it— could determine whether a band had a robust career or not.

Between 1970 and 1972, Deep Purple had produced Deep Purple In Rock, Fireball and Machine Head with this lineup, building up their worldwide profile with successful tours from Scandinavia to Australia, Italy to North America. But this was a band about to implode: by June 1973 Gillan and Glover would be gone, but not before a few more triumphs, trials and tribulations.

Deep Purple’s 1972 tour schedule was brutal, and to compound the difficulty a few shows into their fourth American tour Blackmore had to be flown home, suffering from hepatitis. The group played a show in Flint, Michigan, as a four-piece before using Spirit guitarist Randy California as a temporary replacement for one gig, but postponed other shows until their guitarist was ready to get back on stage, which was eventually scheduled for May 25 in Detroit.

Deep Purple was supposed to make their first visit to Japan in mid-May, but the dates were postponed to August 15-17. The Warner Bros. affiliate in Tokyo had been clamoring to have the band record a live album for release only in their country. The group had serious reservations about the idea. Live albums at the time were often hastily constructed stopgaps between studio albums, recorded on less-than-optimal portable equipment. But because bootleg LPs of Deep Purple shows were starting to show up in the “grey market,” they reluctantly agreed to participate, as long as they could have their studio engineer Martin Birch obtain the best possible recording equipment and supervise the live sound.

The resultant double-LP was called Live In Japan in that country when it was originally released on Dec. 8, 1972, but Warner and EMI didn’t keep it a local phenomenon for long, and titled it Made In Japan when it came out internationally. The U.S. release was in April 1973, four months after EMI’s, because Warner wanted to issue the completed studio album Who Do We Think We Are first. It had been recorded on a mobile studio in Frankfurt and Rome in between live gigs.

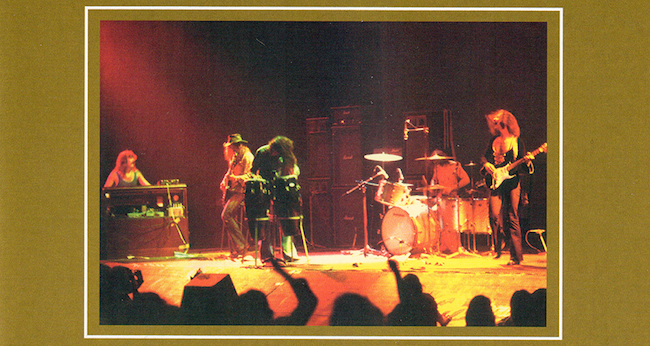

Made In Japan was recorded for a total of about $3,000, according to Lord. Performances were drawn from sold-out shows that were hyped up tremendously by the Japanese music press, two at Festival Hall in Osaka and one in Tokyo’s Budokan arena. Birch, still dissatisfied with the recording equipment available, was forced to monitor the show from a control desk backstage rather than from “front of house” as was usual. Japanese audiences were much less rowdy than American or British crowds, and listened attentively, only applauding politely at the end of a song. Though somewhat disconcerting to the band on stage, the decorum contributed to the clear sound quality Birch captured.

The raw 8-track tapes weren’t overdubbed at all. In fact, Birch says Gillan and Blackmore never even heard the tapes before release, and only Paice and Glover showed up for hasty mixing sessions. In a 2014 interview, Lord explained, “Ritchie and Ian weren’t getting on well offstage, but onstage, there was still a massive, important amount of chemistry.”

“It was just good fortune that we recorded that album at the peak of our performing abilities,” Roger Glover said.

The playlist on the original double-LP featured seven songs, four of them from Machine Head, including an epic workout on “Space Truckin’” that took up an entire LP side, clocking in at 19:42. A monumental “Highway Star” kicks off side one, with its awesome slow build grabbing the audience’s attention from the start. The band is absolutely in top form: Gillan is every bit as commanding as Robert Plant or Roger Daltrey, and the Glover/Paice beat drives it all with power. The extended soloing is astonishing: Lord’s organ solo is a scorcher, and Blackmore has a couple of minutes out front that recall the audacity of Jimi Hendrix or Jeff Beck. For much of the time he sounds like he must have at least four hands.

“Child In Time” from Deep Purple In Rock had become one of the band’s most dramatic tunes as it grew muscle during their incessant touring. Paice uses his cymbals to create a chiming backdrop to Gillan’s expressive, quiet storytelling, and then explodes with him when he goes from a whisper to a scream. During live performances of “Child In Time,” Blackmore’s literal moment in the spotlight would find him throwing his guitar in the air, pulling classic rock star poses, slamming his whammy bar, and executing incendiary runs that fused blues, metal and psychedelic elements. As he once told a Guitar World interviewer, “I didn’t give a damn about song construction. I just wanted to make as much noise and play as fast and as loud as possible.”

“Smoke on the Water” is the only track drawn from the Aug. 15th show (the Aug. 16th show supplies most of the album content), and somehow it bests the studio version. It’s so energetic, it verges on chaos at times, but the band knows exactly how far to push it. Lord and Blackmore again excel. Warner Bros. took the opportunity to issue a 45 rpm single coupling an edit of the Osaka performance with the Machine Head version, and AM and FM radio stations alike jumped on it, helping drive it to #4 on Billboard’s Hot 100, thereby matching the highest entry of Deep Purple Mark I, 1968’s “Hush.”

Related: How “Smoke on the Water” came to be

“The Mule,” originally on Fireball, is a feature for Paice, who gives it his best Ginger-Baker-with-a-side-of-Buddy Rich panache. He even gets the staid Japanese audience whistling, shouting encouragement and clapping along. In the last two minutes, the band joins in to execute a kind of demented Chuck Berry riff, and then an all-out psychedelic/prog-rock freakout. At a time when drum solos were starting to feel stale, with just about every live rock show featuring one, Paice makes you pay attention.

“Strange Kind of Woman” (with some nutty call-and-response vocal/guitar/drums improvisation starting around the five-minute mark) and “Lazy” (the only track from Tokyo) fill side three. Throughout the 11 minutes of “Lazy,” Lord echoes jazz-blues organists like Jimmy Smith and Richard “Groove” Holmes. He leads with an extremely “overdriven” Hammond organ intro, throwing in a bit of “Louie Louie” and Duke Ellington’s “C Jam Blues,” before Blackmore leads the whole band into the massive riff that blew a thousand speakers. In the waning moments, he toys with Hugo Alfven’s “Swedish Rhapsody #1” melody.

“Space Truckin’” has room for every effect in the Deep Purple arsenal. The band interaction is truly impressive, whether they are executing a designed set-piece or launching an unplanned hunk of impromptu magic. The whole performance is capped with an ending full of fireworks, with Blackmore going full Hendrix a la “Machine Gun.”

The audience is clearly stunned, and is silent for a moment until exploding into raucous applause as Gillan bids them goodnight.

Made In Japan has been reissued on CD numerous times, with many alterations in track sequence and the addition of cuts not on the original: the 2014 boxed set is the most complete. The current Deep Purple lineup (Mark IX) released a new album, Turning to Crime, on November 26, 2021. According to Ian Gillan, they have no plans to retire. And why the hell should they?

Related: Our Album Rewind review of Deep Purple’s Machine Head

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

3 Comments

I love Robert Plant, but Gillan has the best voice, hands down.

Well, that’s an excellent article and yes, that is an epic jamming on that record. Richie Blackmore is in another world as his most of the band 72 will never be duplicated so many great tours went on that year.

Deep Purple is one bad ass band. The Mark II line-up is definitely the best but Joe Lynn Turner did an exceptional job as their lead singer for the album “Slaves & Masters.” If Ian and Ritchie could have just gotten along better, DP would be right up there with Led Zeppelin as the Greatest Hard Rock Band.