Some albums are born in turmoil, and Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett’s only Elektra album, Accept No Substitute, is one of them. It’s a beautiful album, close to perfection in the playing and singing, a fusion of white soul, gospel and country that set a certain tone for decades to come (the Tedeschi-Trucks Band, Black Crowes and Marcus King Band are only three of the later groups to proudly wear their Delaney and Bonnie obsession).

Some albums are born in turmoil, and Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett’s only Elektra album, Accept No Substitute, is one of them. It’s a beautiful album, close to perfection in the playing and singing, a fusion of white soul, gospel and country that set a certain tone for decades to come (the Tedeschi-Trucks Band, Black Crowes and Marcus King Band are only three of the later groups to proudly wear their Delaney and Bonnie obsession).

Yet, during its recording in 1969 at the brand-new Elektra Sound Recorders on La Cienega Blvd. in West Hollywood, supervising producer David Anderle, engineer John Haeny and prime mover Delaney Bramlett screamed at each other, stalked out of sessions and fought over recording techniques, musical direction and credits. The married couple at the center of a large band of friends and collaborators had a tempestuous relationship; more than one witness saw Bonnie come to the studio in dark glasses to hide the latest black-eye allegedly inflicted by her husband. The sessions included musicians who would seed Eric Clapton’s Derek and the Dominos, Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen, and play a key role in the recording of George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. More than one observer described the talent of the sidemen as “unbelievable”: Bobby Keys (sax), Jim Keltner (drums), Leon Russell (guitar/piano), Bobby Whitlock (organ), Carl Radle (bass), Jim Price (trumpet/trombone) and Rita Coolidge (backing vocals) among them.

Related: Our interview with band member Bobby Whitlock

In interviews and memoirs over the years, everyone involved continued to diss each other and argue about what actually happened. Delaney told an interviewer, “Anderle, all he would do was sit around and roll joints.” Anderle once said the conflict between Haeny and Bonnie led to “the most painful studio time in my life. They got me so nuts I hadn’t eaten for weeks.” At one point he kicked Bonnie out of the building and fired Haeny, telling him, “God love you, but I cannot put up with your shit anymore.”

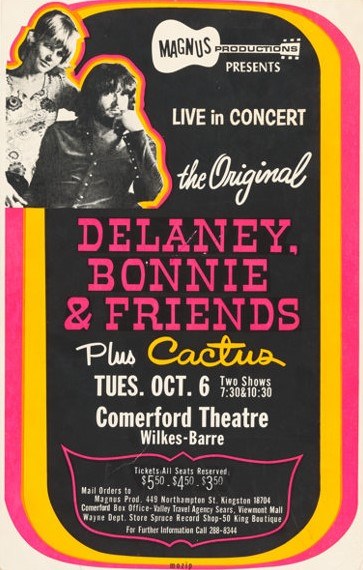

Watch a 45-minute concert by Delaney and Bonnie from 1969

Remembering his reservations about signing Delaney and Bonnie in the first place, label head Jac Holzman wrote in his autobiography Follow The Music, “I was wary of them as people. Something about Delaney made me itch…we had crossed into the twilight zone. They charged through Elektra leaving a large and upsetting wake.”

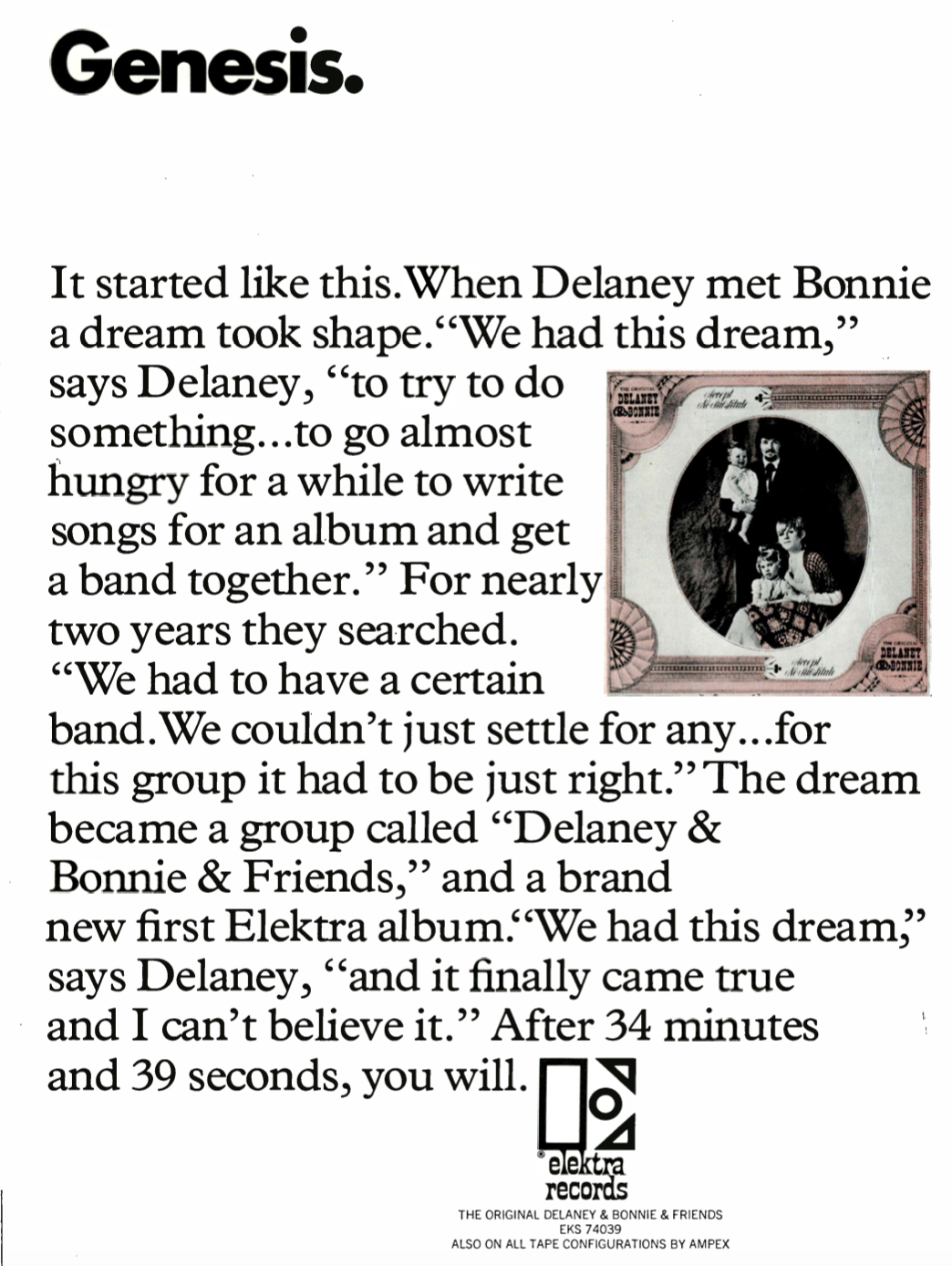

[When the album was released in June 1969, Elektra Records placed ads in the music business trade magazines that quoted Delaney. “We had this dream,” he said, “to try to do something… to go almost hungry for a while to write songs for an albums and get a band together. We couldn’t just settle for any… for this group it had to be just right.”]

Eventually, after the album sold a disappointing 50,000 copies and only reached #175 on the Billboard album chart, a number Delaney thought was fully Elektra’s fault, he reportedly threatened, during an overseas phone call, to kill Holzman, who told him to “go terrorize some other label,” releasing D&B from their contract on the spot.

Ironically, “We’ve got to get ourselves together/take some time and talk it over/we’ve got to get ourselves together/try to understand each other” are the first lyrics sung on the album. Delaney and Bonnie establish an easy harmony with each other (duos like the Louvin and Everly Brothers no doubt in their minds), then individually weave their voices to-and-fro as the opener “Get Ourselves Together” (written by Bonnie and Radle) continues. The lead guitar stings from the very first snaking intro line, the horns provide apt accents, and the whole production has a propulsive R&B swing to it. A tidy 2:33 and not a wasted moment—quite a confident announcement of the album’s quality.

Delaney begins “Ghetto,” with Leon Russell’s unmistakable gospel piano and Jimmie Haskell’s string arrangement in support: “If you’ve ever lived in a ghetto/It may be at the close of your day/On your front porch you hear the sound of a jukebox/From a neighborhood café.”

The track builds in intensity, Delaney going into falsetto over a gospel chorus, then full preaching/screaming mode kicks in (Ray Charles was one of Delaney’s heroes). The tune, from veteran Memphis songwriters Bettye Crutcher and Homer Banks (plus Bonnie), was first recorded the previous year by the Staple Singers with Mavis Staples leading, which might account for why D&B transferred it to the male voice for their rendition. Bonnie could compete with Mavis when it came to serious soul, but why invite the comparison unnecessarily?

“When the Battle is Over” fades in slowly, with all cylinders clicking and Russell, Radle and Keltner super-funky from the get-go. (There are no individual track credits on the LP, it sounds like Ventures guitarist Jerry McGee doing the crisp lead on this one.) Bonnie enters with sass, taking the first verse with a hint of Billie Holiday in her voice, and Delaney picks up the sexy vibe on the second verse. The chorus lyrics ask, somewhat mysteriously, “When this battle is over who will wear the crown? Will it be you, will it be me?” New Orleans legends Dr. John and Jessie Hill wrote the song, with Dr. John coming into the D&B L.A. sessions, at Russell’s urging, to teach the band how it went. He was trying to kick heroin at the time, and was sweating and shaking as he played the piano, eventually skipping out to vomit in the bathroom. The skillful build of the track, with the dynamics ramping up with each chorus, finally has the lead vocalists and chorus wailing away, Whitlock’s organ moving to the fore. It finishes nearly a cappella, in happy exhaustion.

“When the Battle is Over” fades in slowly, with all cylinders clicking and Russell, Radle and Keltner super-funky from the get-go. (There are no individual track credits on the LP, it sounds like Ventures guitarist Jerry McGee doing the crisp lead on this one.) Bonnie enters with sass, taking the first verse with a hint of Billie Holiday in her voice, and Delaney picks up the sexy vibe on the second verse. The chorus lyrics ask, somewhat mysteriously, “When this battle is over who will wear the crown? Will it be you, will it be me?” New Orleans legends Dr. John and Jessie Hill wrote the song, with Dr. John coming into the D&B L.A. sessions, at Russell’s urging, to teach the band how it went. He was trying to kick heroin at the time, and was sweating and shaking as he played the piano, eventually skipping out to vomit in the bathroom. The skillful build of the track, with the dynamics ramping up with each chorus, finally has the lead vocalists and chorus wailing away, Whitlock’s organ moving to the fore. It finishes nearly a cappella, in happy exhaustion.

“Dirty Old Man” (Delaney penned it with Mac Davis) finishes the side with yet another fantastic Bonnie rave-up, showing off her Aretha-like ability to change gears within a syllable.

Side two starts with “Love Me A Little Bit Longer,” which sets the template for what Eric Clapton’s first solo album was going to sound like when he borrowed Delaney and Bonnie’s band the following year.

The bluesy “I Can’t Take It Much Longer” is another slice of heaven, with a loping rhythm, terrific horns and more great guitar fills (possibly from Delaney).

At more than five minutes, the version of Dan Penn and Chips Moman’s “Do Right Woman” is the album’s longest cut, and it bests every other version (Aretha Franklin, Flying Burrito Brothers, Etta James and Otis Clay included). The ache of love under pressure comes through, with each singer pleading for understanding: “Take me to heart/And I’ll always love you/And nobody can make me do wrong/Take me for granted/Leaving love unsure/Makes willpower weak/And temptation strong.”

Given what Delaney and Bonnie’s marriage was like, you wonder what they were really thinking when they recorded it (they divorced in 1972). It’s a gut-wrenching, “deep country” performance. By the time Bonnie’s singing, “They say that it’s a man’s world/But you can’t prove that by me/As long as we’re together baby/Show some respect for me,” with Haskell’s swirling string arrangement as a cloud around her, she totally owns it.

The traditional gospel tune “Soldiers of the Cross” is started by Russell, and he propels the whole track with big help from Keltner. Bonnie’s in full control, even when the band kicks into double-time midway. She really “feels the spirit,” shifting spontaneously into another gospel standard, “This Little Light of Mine,” for the duration. Another Mac Davis-Delaney Bramlett gospel-infused song, “Gift of Love,” completes the album, with a Memphis-meets-New Orleans feel (Jim Price on trombone plays a kind of mock-tuba part).

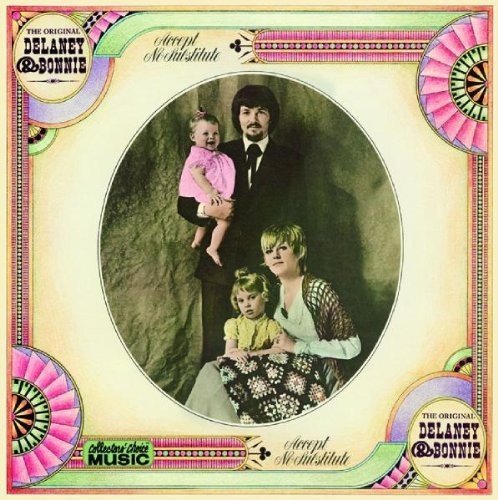

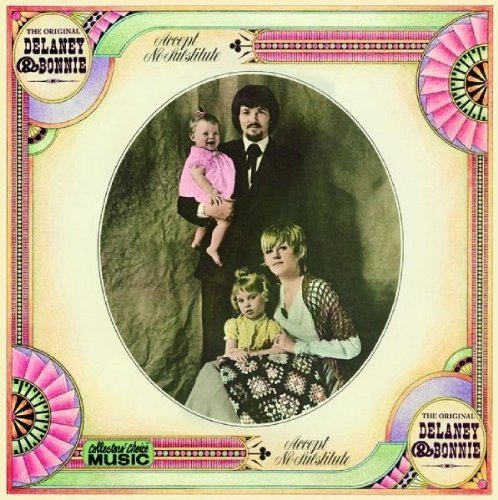

In a particularly weird coda to the recording sessions, a fight broke out regarding who even owned the recording. Holzman’s contractual terms with the band had been very generous, granting them, for instance, control over the art direction (ticking off Elektra’s in-house ace designer Bill Harvey). They dressed the sleeve in old-timey tinted black and white photos of everyone involved (except Holzman, Harvey and the “silent partner” in D&B’s management Sid Keiser, who they listed as “out of town”).

The photos conveyed the “family feel” they wanted, but didn’t really say anything about the sound of what was inside the sleeve. Anderle and Holzman loved the album, despite what it’d taken to get it made.

Listen to “Soldiers of the Cross”

Delaney and Bonnie’s manager Alan Pariser sent some test pressings over to England, and before release the album became a favorite of Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton and George Harrison. Like Music From Big Pink, it shifted attention, through its rootsy approach, from England to the United States. The about-to-be-ex-Beatle liked it so much he wanted to release it on Apple, and David Anderle claims he even has a copy with an Apple label on it.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Clapton’s debut solo LP

Elektra representatives rushed to London when they heard Delaney had actually signed a contract with Harrison. In his book, Holzman quotes Anderle as saying, “We said to them, ‘Excuse me, guys, this isn’t Mississippi. You can’t sign a contract with us and then, just because you fall in love with a Beatle, go off with Apple.’” The Apple contract was voided. (An offshoot of the trip was that Anderle hung out with Jagger some, and the Rolling Stones decided to finish recording Let it Bleed at the Elektra studios in Los Angeles, which helped cement Elektra Sound Recorders’ new reputation as the hip place to hang out.)

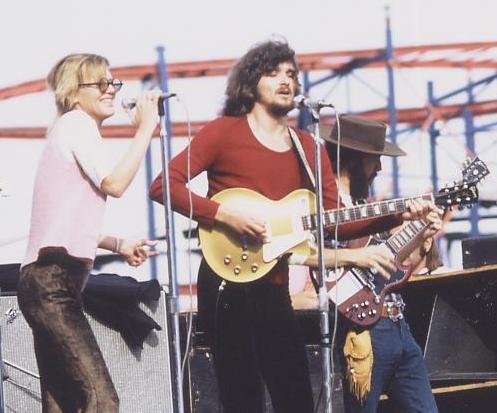

For Delaney and Bonnie, the next step was touring with Blind Faith, eventually letting a disillusioned Eric Clapton join their band, and…well, that’s another story.

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

5 Comments

Copies of the record were indeed pressed on Apple records, though no sleeves were printed. Needless to say, it is a very pricey piece of vinyl, IF you can find a copy.

https://www.discogs.com/Delaney-And-Bonnie-The-Original-Delaney-And-Bonnie/release/5519850

I may be in the minority here,but none of the

behind-the-scenes antics neither surprise

or interest me.Probably

more than we’ll ever know, this anger and

tension on the brink

took place maybe more

often than not,any time.

The air of hostility may

have placed a pall of ire

over all concerned,

but in the end, did not the vitality and creativity

conquer all in the end?

This was an excellent lp.

Besides their official

releases,the warmth of

the RHINO HANDMADE

box displayed what was

all that really mattered,a

wonderful collaboration

of sterling musicians.

Their individual voices were too thin to front blues songs performed by a full band. Especially Delaney. When they sang together, it was fine, and when the arrangement left Bonnie space, she could get by. But in many cases the band behind them just overpowered their voices. Obviously engineers could have compensated and who knows, maybe they tried and the artists rejected the results.

So odd to see this cuz I just got their greatest hits from the library. I was wondering about Delaney cuz this summer I bought the full set of every episode of “Shindig” and Delaney was a member of The Shindogs ( w James Burton on lead guitar ) and they were really good. Delaney & Joey Cooper did the singing and both were really good.

I’m looking to find something on Joey. (another trivia fact both James and Glen D.Hardin the Shindogs keyboardist, went on to play with Elvis).

A great duo….too bad their personal lives caused them to implode. Bonnie Bramlett went on to a critically hailed solo career but with stillborn sales….which is too bad as she is one of the best.