Even among one-hit wonders, “Israelites,” the 1969 hit by Desmond Dekker and the Aces, was an outlier. For one thing, the singer and his group were from Jamaica, the Caribbean island that, despite being only about a thousand miles from the Florida coast, was, in those days, far from the consciousness of the American record buyer. Prior to the arrival of the Dekker hit, only Millie Small, the Jamaican teenager whose squeaky, effervescent “My Boy Lollipop” had made it all the way to #2 on the Billboard singles chart in 1964, had caught the fancy of stateside music fans.

Even among one-hit wonders, “Israelites,” the 1969 hit by Desmond Dekker and the Aces, was an outlier. For one thing, the singer and his group were from Jamaica, the Caribbean island that, despite being only about a thousand miles from the Florida coast, was, in those days, far from the consciousness of the American record buyer. Prior to the arrival of the Dekker hit, only Millie Small, the Jamaican teenager whose squeaky, effervescent “My Boy Lollipop” had made it all the way to #2 on the Billboard singles chart in 1964, had caught the fancy of stateside music fans.

Listen to the original hit recording of “Israelites”

Compared even to “My Boy Lollipop” though, “Israelites” was positively alien. The former, sung by Small in the then-popular Jamaican bluebeat dance style (it could also be considered an early ska recording), was a recording made for a very young audience. “My boy lollipop,” she sang, “you make my heart go giddy-up/You are as sweet as candy/You’re my sugar dandy.” That single—actually written in the ’50s by a member of the American doo-wop group the Cadillacs as “My Girl Lollypop,” and given its gender change when recorded by Barbie Gaye in 1956—was a big enough hit for Small that it launched the career of her producer, Chris Blackwell, who would become the mega-entrepreneur head of Island Records and help jumpstart the careers of Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, U2 and many others.

Related: Millie Small died in 2020

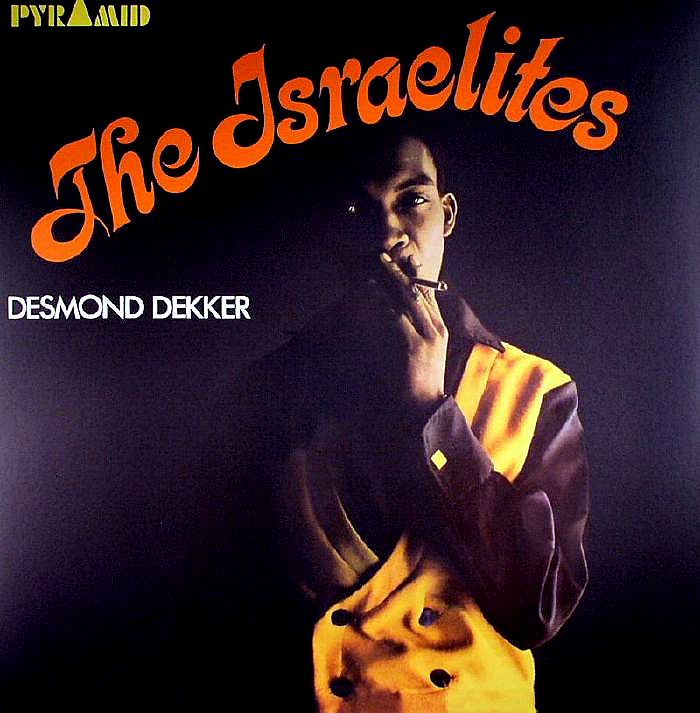

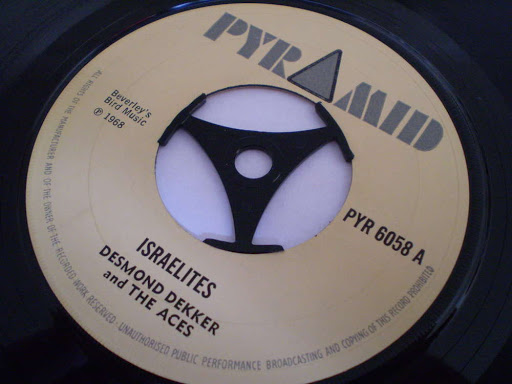

“Israelites” was something else altogether, and seemingly came out of nowhere, at least in the United States. In the U.K., however (as well as in his homeland), Dekker was already a known quantity. Born Desmond Adolphus Dacres (or Dacris) on July 16, 1941 in Jamaica, his 1967 recording “007 (Shanty Town),” on the Pyramid label, had found its way to #14 in England. By the time he returned with “Israelites,” the British audience was ready for more of the exotic music he had to offer.

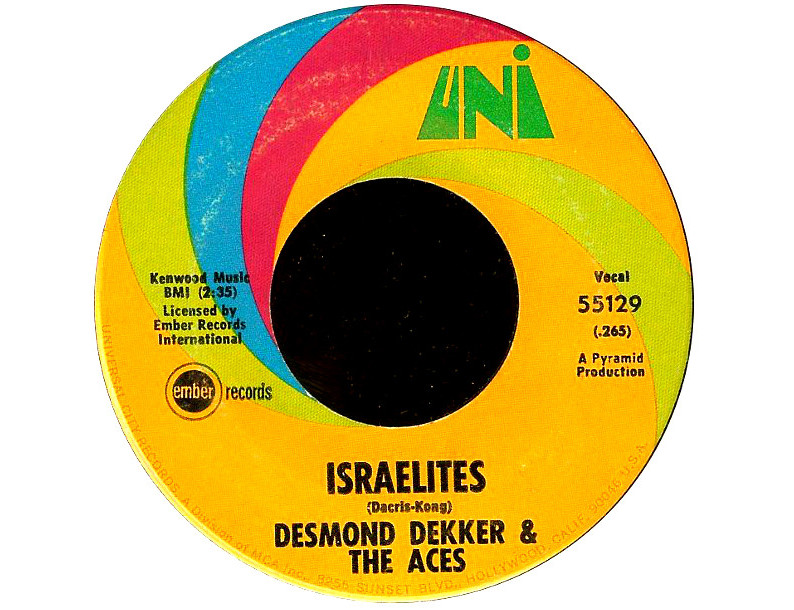

The song was written in 1968, its authorship shared by Dekker and Leslie Kong, a record label owner and budding record producer in Jamaica who gave the young Jimmy Cliff his start. (Kong would go on to become one of the most renowned producers on the island.) With the success of “Israelites,” Kong and Dekker broke into the international market in a big way: the single reached #1 in the U.K., #9 in the U.S. in late June 1969 (on Uni Records, home of the Strawberry Alarm Clock) and also made the top 10 in more than a dozen other countries, including Canada, Australia and several European nations. “Israelites” was a genuine worldwide hit,

But what the heck was it about? Few listeners at the time had any clue whatsoever what Dekker, in his thick Jamaican patois, was singing. Do you? We’re guessing that when you sing along to it, you make up your own words (“Get up in the morning slaving for breakfast?”)

Before we get to the words, let’s take a look at the title. Why “Israelites”? Were Dekker and Kong commenting on the recent Six-Day War that pitted Israel against a number of Arab states? Were they expressing admiration for the Jewish people or other residents of the arid desert land?

We’ll defer to the uncredited author of an entry on the song in The UK Number Ones Blog. That person wrote, “The title refers to Rastafarianism, which has its roots in Israel…Rastafarians were second class citizens in a predominantly Christian Jamaica, and often had to struggle to make ends meet. But, like all the best songs-with-a-message, ‘Israelites’ doesn’t forget to be catchy. It works as well on a basic level, one that you can shake your body to, as it does as a social commentary.”

We’ll defer to the uncredited author of an entry on the song in The UK Number Ones Blog. That person wrote, “The title refers to Rastafarianism, which has its roots in Israel…Rastafarians were second class citizens in a predominantly Christian Jamaica, and often had to struggle to make ends meet. But, like all the best songs-with-a-message, ‘Israelites’ doesn’t forget to be catchy. It works as well on a basic level, one that you can shake your body to, as it does as a social commentary.”

Indeed, as the Wikipedia entry titled “Judaism and Rastafari” states, “Judaism and Rastafari closely align in essence, tradition, and heritage, as both are Abrahamic religions,” although it goes on to say that there are vast differences in the beliefs, customs and practices that are tenets of the two religions. Rastafari, which developed in the 1930s in Jamaica, for example, is based on a belief that the then-emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, was a “living god,” a prophet referred to as Jah. No faith based in Israel came close to echoing that belief.

The relationship between religious philosophies fostered in Israel and Rastafarianism are best studied in another place. Our concern right now is why Desmond Dekker named his song “Israelites,” and that perhaps shall remain a mystery, although some have speculated that Dekker and Kong used the word to equate the struggling subject of the song with that of God’s “chosen people” of Israel.

The lyrics don’t exactly give much of a hint—that is, if you can make them out. We’ve been trying for several decades and finally decided to look them up. We were surprised—but not that surprised—to find out that we’ve had much of the song wrong all these years. We were also not very surprised to learn that some websites that display song lyrics show conflicting words for “Israelites.” We gave a few close listens to try to figure out what Mr. Dekker and his Aces are actually singing.

The song—which is performed in a rocksteady or ska rhythm that hinted at the reggae style that would emerge from Jamaica a few years later—starts with a simple declaration

“Get up in the morning, slaving for bread, sir, so that every mouth can be fed.”

So far, so good—we knew that one.

After that comes the tag line, “Poor me, Israelites.” The Aces then echo each verse sung by Dekker with those three words, all the way to the end of the song.

OK, we missed that. We always thought he was simply saying, “Oh, oh, the Israelites.” His version makes more sense. This is why we’re writing articles about songwriters instead of writing songs.

Dekker then repeats the exact same opening lyrics before moving on to the next verse:

“My wife and my kids, they packed up and leave me/Darling, she said, I was yours to be seen,” or, according to other lyric sites, “yours to receive.” Either way, she’s outta there.

Related: Looking back at the music of 1969

Not even close to what we thought he was singing. Maybe that’s because, other than “to be seen,” or “to receive,” we had none of it right. And what exactly does “I was yours to be seen” mean, anyway (if that is indeed what he’s singing)?

Now the story is unfolding in a way that we can kind of understand. The singer is being dumped for being too poor. It’s a status that’s formed the basis of many a song, in every genre, throughout history.

Carry on, Desmond. Tell us what happens next.

“Shirt them a-tear up, trousers a-gone/I don’t want to end up like Bonnie and Clyde.”

OK, we always knew that he didn’t want to end up like Bonnie and Clyde. That line is pretty legible. Who would want to end up like a couple of wild, dead gangsters? That is not a good way to end up. He’s telling us he doesn’t want to have to resort to crime and get filled with lead; that’s understandable.

But the first part? What’s up with the torn shirt and missing pants? We’re back in head-scratching mode here. Did she tear his shirt up and steal his pants? Or is he saying that he’s now so poor that he’s going around half-naked? This guy is in pretty sorry shape.

Continue, please:

“After a storm there must be a calm/They catch me in the farm, you sound your alarm.”

Huh? The first bit about a storm—never knew that. But after that? It gets even more perplexing. What farm? Who’s talking about a farm? Why is he on a farm now? No one was asking about a farm. At least we kinda knew that last line about sounding the alarm.

We should remind you, by the way, that every one of these little mini-verses is still ending with “Poor me Israelites.” He’s really pounding that one home.

Related: Admit it, you don’t know the lyrics to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Green River” either

Following the alarm, the entire song goes back to square one for a second round, complete with fleeing wife and kids, trousers, alarms and poor Israelites. There’s one short aside, which Dekker tucks in toward the very end: “I wonder who I’m working for.”

And with that, “Israelites” is yours to be seen (or received)…

The recording, as we noted, went on to become an international smash, and Desmond Dekker—who would become a U.K. resident in 1969, the year of “Israelites”—would enjoy a long career. Or perhaps he would only enjoy it until 1984, when he declared bankruptcy. He died of a heart attack in 2006, at his home in London.

Among his fans was one Paul McCartney, who, in 1968, wrote a new song called “Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da” for the Beatles, in the ska style. The song’s opening line, “Desmond has a barrow in the marketplace,” was a tribute to—you guessed it, the man whose “007 (Shanty Town)” had been a big hit in the U.K. even before “Israelites.” (It would be featured on the soundtrack to the 1972 film The Harder They Come, which introduced many to reggae music.)

Watch the official music video for “007 (Shanty Town)”

Speaking of which, if you think the lyrics of “Israelites” are difficult to discern, you don’t even want to know about “007.”

Watch Desmond Dekker perform “Israelites” live in 1990

Dekker died on May 25, 2006, in London, U.K. He was just 64.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

6 Comments

Excellent, as usual. May I tell you that I have been friends with The Slickers since 1973 when I was a school teacher in Jamaica. Hylton Beckford is alive and well and we have a great new “album” in the can with guests Liberty DeVitto, Julio Fernandez, Richie Canatta, and Andy Falco (on his old Tele on two cuts). As he is getting ready to celebrate his 75th birthday in November, we have some summer concerts lined up in Keene Valley, NY, in the heart of the Adirondacks in September. His song, Johnny Too Bad, came in at #19(!) on the Apple TV+ documentary “1971: The Year Music Changed Everything”. Sure would be great to get him some recognition as everyone from Garcia to Capaldi to Taj Mahal to John Martyn to Jimmy Cliff, Bunny Wailer and every garage band ever covers this song. It is the reggae “Louie Louie” as everyone knows the song but few know the Kingsmen.

I lived in Victoria BC for a few years after a life spent in Los Angeles and New York. It’s close to my native home and clearly a beautiful city but I was scheming to get back to the states and to a place that never sleeps, much less falls asleep in a chair after a cup of tea the way Victoria does. I’d taken to Desmond Dekker after watching Drugstore Cowboy, a hypnotic film partly thanks to its use of Dekker’s Israelites in the soundtrack. Weekends with nothing to do saw me rolling around the outskirts of town in a lid-free FJ-40 and Dekker on the aftermarket stereo. like a drug but not as helpful. At least twice while stopped for a light I was asked by pedestrians what music I was playing. Later, on a very lucky work-funded stay in Paris on the cheap, I brought Desmond of course and because my accommodation was a co-house-sitting gig in partnership with an adorable French illustrator, another fan of the man was won. I left the disc behind along with a pile of dirty dishes. Just kidding. I left the music.

Dekker couldn’t fix Victoria for me, though. Until he did. Danged if the son of the gun didn’t finally get a chance to tour in North America. He’d been banned because of a pot bust or the like. He hit Seattle and was kind enough to take a day of annoyingly slow travel to reach his ailing fan in BC. He played a very small club but he and his band and his dancing boy filled it up to 100 times its physical size. I thank pour almighty planner for letting someone pencil that one in. It was a boost if not a rocket. I found a way to slither back to the states not too long after that. Good memories began to accumulate again and even Victoria falls on that good side of the divide when I venture to think about it. The second best act that made the trip was Jonathan Richman. He is always on, near as I can tell, but he was on, up, and everywhere that night. “Of course he needs you. He’s a musician. ” I guess none of us had ever heard that one, but he tells it fairly often. Canadians were falling down, Jo-Jo was happy and I lived another day.

Desmond Dekker left to meet God, I bet. I bet he was summoned. That’s a pleasing thought but consequently we don’t get any refills of his magic. I’m going to offer an artist that I think some of those feeling post-DD emptiness can use to fill it. This fellow has a quirky story and a unique sound. I read about him some place and had a hunch he was right up my alley. Indeed, I got a lot of play out of my first William Onyeabor purchase. I brought it to an art class to play while we were drawing, at the invitation of the teacher. My fellow students didn’t pay much mind but our teacher, a woman who came from Japan to study in the 1960s and ended up marrying and staying really took to it. I gave her the CD I had burned it onto and made another copy for my car later. Poor me.

Good article! I think the “they catch me in the farm, you sound your alarm” line is referring to a marijuana farm. Rastas smoked weed during meditation and prayer despite it being illegal in Jamaica. It’s one of the reasons they were ostracized in Jamaican society

I’m fairly certain that the wife’s line is:

“Darling” she said, “I was the last to receive.”

That actually makes sense within the context of the song as well!

I could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure the wife says the following:

“Darling,” she said, “I was the last to receive.”

This certainly makes sense within the context of the other lyrics.

Me ears are a-light . . .