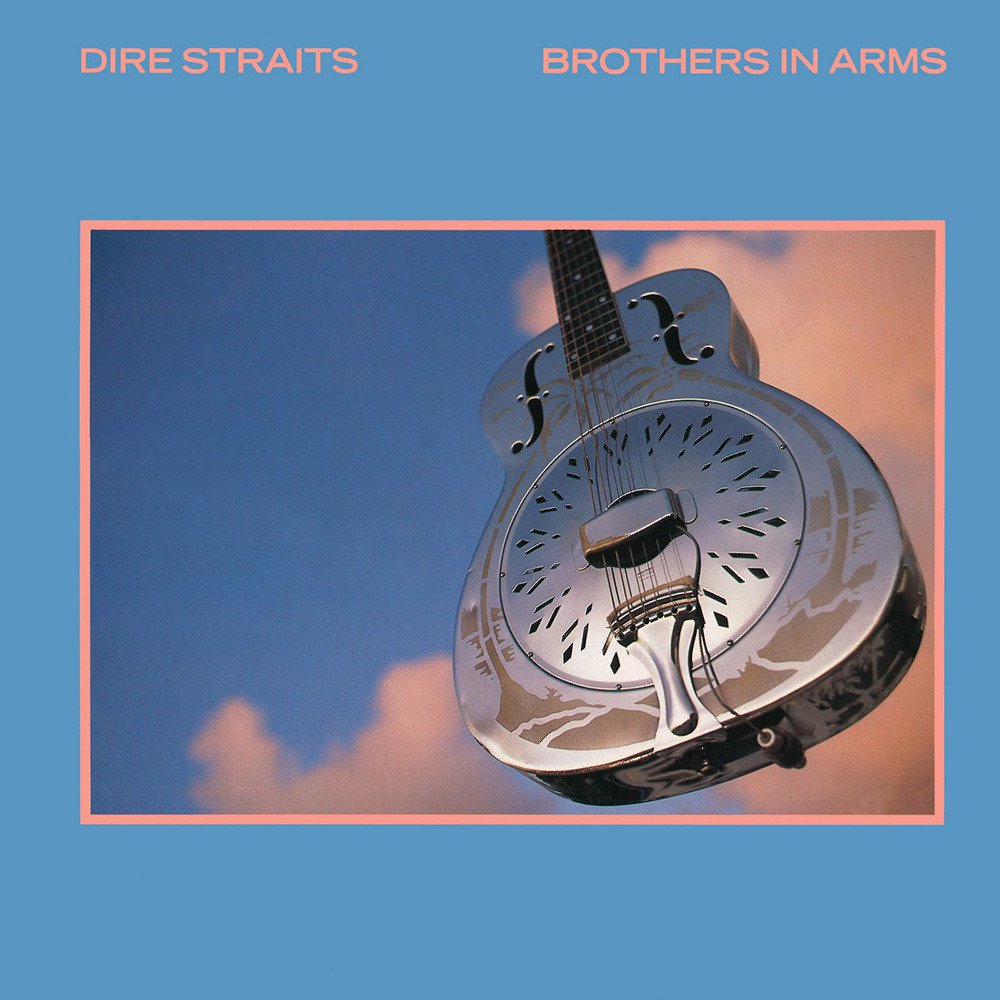

With their fifth album, Brothers in Arms, Dire Straits vaulted from platinum respectability to the commercial ionosphere—album chart bragging rights in more than a dozen countries, multiple-platinum sales that would cast a long shadow over British pop culture and new notoriety as music video darlings. Catalyzing that global conquest were new wrinkles in media and recording technology that partially eclipsed their musicianship after the set’s release on May 17, 1985. Key to extending their reach was a groundbreaking music video that teased MTV’s kingmaking clout just before the service crossed the Atlantic with the splash of Live Aid’s July benefit concert, which included the band among its headliners.

With their fifth album, Brothers in Arms, Dire Straits vaulted from platinum respectability to the commercial ionosphere—album chart bragging rights in more than a dozen countries, multiple-platinum sales that would cast a long shadow over British pop culture and new notoriety as music video darlings. Catalyzing that global conquest were new wrinkles in media and recording technology that partially eclipsed their musicianship after the set’s release on May 17, 1985. Key to extending their reach was a groundbreaking music video that teased MTV’s kingmaking clout just before the service crossed the Atlantic with the splash of Live Aid’s July benefit concert, which included the band among its headliners.

Equally pivotal was Straits singer, songwriter and producer Mark Knopfler’s embrace of digital tech, recording on multi-track digital machines and releasing an expanded version of the album on compact disc two years after the format’s rollout. The band’s U.K. label, Vertigo, was tied to Philips, the Dutch multinational conglomerate that shared development of the shiny optical discs with Sony. Brothers in Arms brought Philips a showcase for CDs, casting Dire Straits as poster boys for the new format and unwittingly inviting critical backlash when Philips’ substantial advertising and promotion tarred them in some critics’ view as corporate shills.

The initial wave of skepticism leveled at the album was most pointed at home, where the British rock press griped about the band’s stadium-scaled firepower and prodigious technical prowess – virtues that were vices to critics rallying behind punk’s rougher DIY edges as badges of authenticity, augmented by sniping over Knopfler’s affection for “Americana” (as one U.K. pundit summarized Knopfler’s affection for American blues, country and early rock ’n’ roll, little dreaming the term would arise as a 21st century genre, one with which Knopfler’s later music would indeed resonate).

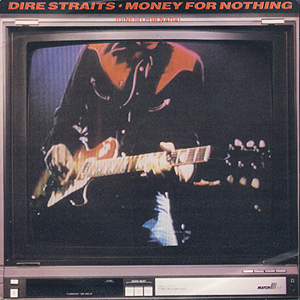

The focal point for the album’s divisive impact and a key driver behind its success was “Money for Nothing,” which rode its MTV namecheck to a commercial bonanza via its music video. With its blue-collar protagonists toiling to install microwaves and hump appliances while rock “yo-yo’s” reaped fortunes “play[ing] the guitar on MTV,” the song wasn’t Knopfler’s first to allude to class issues, but its just-in-time arrival as the channel reached an inflection point buried that subtext beneath its videogame-inspired 3D animation.

Knopfler had inserted the platform’s slogan, “I want my MTV,” echoing the Police hit, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” with a vocal cameo from Sting himself. The lead Police man was windsurfing on Montserrat while Dire Straits was recording at George Martin’s AIR Studios compound and joined them for dinner. When they previewed the track for him, Sting raved at the concept and readily added his part, singing harmony on the verse and choruses and chanting the MTV mantra as both intro and extended coda. (It was his music publisher, Virgin, that heard the track and demanded Knopfler award a royalty and writing credit, much to Sting’s embarrassment.)

The track also owed a sonic debt to ZZ Top. Knopfler, a guitar hero with a sinuous Stratocaster touch, wanted to lean toward the brawny, serrated tone Top’s Billy Gibbons unleashed on his Les Paul, experimenting with his own Gibson when co-producer and engineer Neil Dorfsman was adjusting microphones and caught the desired buzzsaw edge heard on the finished track.

The decision to record on Sony’s new 24-track digital system stemmed from Knopfler’s ongoing quest for pristine recordings, enabling the band to have the project join the short list of albums recorded, mastered and replicated in the digital domain for release on compact disc. Less than three years after its release, the format was being touted for its sonic superiority and longer playing times, exploited by Knopfler and Dorfsman with longer edits on four of the five tracks on the LP’s first side, extending the running time by nearly 10 minutes.

That meant nearly two more minutes of the already generous eight-minute “Money for Nothing” LP edit, following a longer version of the album’s opening track, “So Far Away,” a languid ballad released as the first single. Heard back-to-back with the analog cut, the longer edit offers no revelations, just a longer coda. Its wry declaration of romantic devotion laced with circumstantial frustration signaled the band’s shift toward a broader pop style relying less on Knopfler’s guitar chops and more on the expanded ensemble’s spacious soundscape and spare synth and guitar accents.

That meant nearly two more minutes of the already generous eight-minute “Money for Nothing” LP edit, following a longer version of the album’s opening track, “So Far Away,” a languid ballad released as the first single. Heard back-to-back with the analog cut, the longer edit offers no revelations, just a longer coda. Its wry declaration of romantic devotion laced with circumstantial frustration signaled the band’s shift toward a broader pop style relying less on Knopfler’s guitar chops and more on the expanded ensemble’s spacious soundscape and spare synth and guitar accents.

Now a sextet with two keyboard players, the band could reach beyond the original quartet’s lean guitar attack with both traditional analog keys in Alan Clark’s piano and Hammond B-3 organ, and nearly infinite digital synth textures from Clark and Guy Fletcher, armed with Yamaha’s new DX-1, several Roland machines and a Synclavier. Clark had already opened the door to those textures on the previous Straits album, 1982’s Love Over Gold, and his atmospheric work on Knopfler’s first soundtrack, 1983’s Local Hero. Between them, Clark and Fletcher were decorating Knopfler’s songs with both broad strokes and delicate effects, with their axe-slinging leader paring back his own guitar heroics to provide a larger canvas.

The sonic modernism afforded by the band’s digital keyboards didn’t erase Knopfler’s affection for earlier styles, as underlined by “Walk of Life,” a brisk shuffle originally intended as a non-album B-side but added to the album at manager Ed Bicknell’s insistence. The track’s indelible synth figure reaches for nostalgia in a reedy, calliope tone closer to an old-school Farfisa as Knopfler sings the praises of Johnny, a busker playing venerable rock ’n’ roll and blues songs associated with Ray Charles, Gene Vincent and other ’50s stars. Its affection for then forgotten musical chestnuts suggested a thematic cousin to “Sultans of Swing,” Dire Straits’ career-launching first single, while extending the upbeat nostalgia the band explored two years earlier on “Twisting by the Pool,” released as an EP.

In addition to the basic tracks cut on Montserrat, Knopfler looked to his widening cohort of jazz and first-call studio musicians encountered since recording Making Movies in New York at the Power Station five years earlier. Local Hero drew him to both traditional British folk music and contemporary jazz leading his writing further afield from earlier material. Had he kept “Private Dancer” for Love Over Gold, critics and fans might have better grasped Mark Knopfler’s pop instincts. (As it stood, the song was far more consequential, a massive “win-win” as the title hit for Tina Turner’s 1983 comeback.)

For Brothers in Arms, Knopfler’s New York guests included drummer Omar Hakim, brought in to replace Terry Williams, the Welsh veteran whose brawny timekeeping had paced Man, Love Sculpture and Rockpile before replacing original drummer Pick Withers. Knopfler opted to furlough Williams in favor of Hakim’s pinpoint percussion on all but the fusillade of drum rolls Williams detonates in the intro to “Money for Nothing.”

New York City’s shadow is longest on “Your Latest Trick,” a moody, after-hours meditation on romantic betrayal given wry noir atmosphere through the interplay of the Brecker brothers, Randy and Michael, on trumpet and tenor sax, respectively, against urban grit and erotic gameplay sketched by Knopfler’s lyrics, its title flexing a double entendre. Knopfler unspools secondary electric guitar figures, but it’s the horn work that elevates the piece even as it steps further away from Dire Straits’ six-string foundations, underlined by extended CD edit.

In either format, Dire Straits frontloads the album with hits while showcasing stylistic expansion. The cynical romanticism of “Your Latest Trick” is succeeded by the hushed “Why Worry,” a tranquil ballad rendered with the tenderness of a lullaby. A latticework of finger-picked acoustic and electric guitars, skeletal percussion and glowing synth motifs cast a sonic balm, the fourth and final of the extended cuts.

With the remaining tracks, Knopfler took a somber left turn on a sequence of antiwar songs. A Latin trumpet fanfare leads into “Ride Across the River,” a battle cry pitting a partisan warrior against a hardened mercenary who “[doesn’t] give a damn who the killing’s for,” the first of three war-torn military ballads. “The Man’s Too Strong” follows as the remorseful confession of “an aging drummer boy” now facing accusations as a war criminal. The penultimate song, “One World,” stumbles, a tangential blues that sketches the “same old news” of failed social harmony.

Related: The story behind “Sultans of Swing”

Knopfler rebounds on the title song, an elegy for fallen comrades inspired by the Falkland Islands War, waged over 10 weeks in 1982 when Argentina seized disputed South Atlantic territory from a small British garrison. Knopfler’s lament echoes traditional folk influences he had explored on Local Hero that would deepen on subsequent soundtracks and solo albums. As the endpoint for the album, “Brothers in Arms” is beautiful, spare and somber, sharing the hush but not the comfort of “Why Worry” as it mourns a pointless war while saluting its dead.

The song would become a familiar concert finale while the titular album would become the first compact disc to rack up platinum sales on its own with the overall tally of 30 million units making it one of the biggest-selling British albums in history, spawning singles with five of its nine tracks and securing Dire Straits’ lofty perch as a stadium-friendly band. Its high-tech bona fides established Brothers in Arms as a benchmark for compact disc’s touted virtues, later sustained by bespoke LP editions restoring the longer CD edits, as well as surround-sound reboots for high-end fans well into the present day.

For Mark Knopfler, the album was as much a trial as a triumph as its success bred ever larger venues and longer tours, evidently feeding his appetite for solo escapes. He would follow his country passions with the Notting Hillbillies a year later, followed by a guitar fan’s dream date with Nashville legend Chet Atkins on 1990’s Neck and Neck, before delivering Dire Straits’ final album, On Every Street, a year later. Knopfler walked away from Dire Straits and their platinum brand quietly, embarking on a solo career in 1996 that has since outrun his old band in duration and output over 27 years and a combined discography of 22 albums.

Bonus Video: Dire Straits and Sting perform “Money for Nothing” at Live Aid 1985

Watch: Mark Knopfler and Chet Atkins perform “Why Worry” with the Everly Brothers as guest vocalists and Michael McDonald on piano

Dire Straits’ recordings, including a live collection, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024