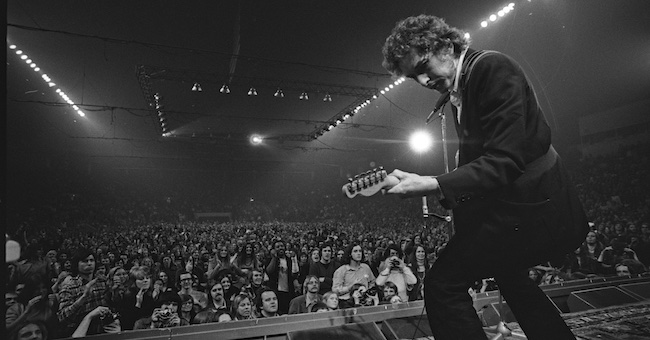

When Bob Dylan and The Band took the Chicago Stadium stage on January 3, 1974, they were greeted by the roar of a sold-out audience exulting at what sounded for many like a Second Coming. Three Chicago shows kicked off an ambitious 40-concert tour, a 21-city trek that ended seven years of relative seclusion after Dylan’s July 29, 1966, motorcycle accident near his Woodstock home. His convalescence abruptly halted the trajectory of his career at a creative peak, punctuated by the release a month earlier of Blonde on Blonde, the magisterial double album that found the ”thin…wild mercury sound” he had been seeking since embracing rock firepower.

When Bob Dylan and The Band took the Chicago Stadium stage on January 3, 1974, they were greeted by the roar of a sold-out audience exulting at what sounded for many like a Second Coming. Three Chicago shows kicked off an ambitious 40-concert tour, a 21-city trek that ended seven years of relative seclusion after Dylan’s July 29, 1966, motorcycle accident near his Woodstock home. His convalescence abruptly halted the trajectory of his career at a creative peak, punctuated by the release a month earlier of Blonde on Blonde, the magisterial double album that found the ”thin…wild mercury sound” he had been seeking since embracing rock firepower.

His last major tour had concluded earlier that year after weathering backlash from a cohort of his earliest fans, even as he galvanized a new audience, backed by a potent live band recruited from the Hawks, a Canadian/American quintet. In the months after Dylan crashed his Triumph, he had woodshedded with the band in the basement of their Saugerties, N.Y., rental, conjuring a new canon of seemingly ancient ballads, blues and surreal broadsides. Reincarnated as The Band, the former Hawks would spread the rustic vision of the “basement tapes” captured in those sessions, beginning with their epochal 1968 debut, Music from Big Pink.

Dylan’s post-accident studio albums were harder to parse, retreating from the potency of his mid-‘60s electric trilogy to pivot toward austerity. 1967’s John Wesley Harding offered terse fables, 1968’s Nashville Skyline swerved toward mellow country, and 1970’s New Morning split the difference, warmed by domestic contentment. Two wild cards—1970’s head-scratching covers twofer, Self Portrait, and 1973’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid soundtrack—further eclipsed the groundbreaking music forged in 1965 and ’66, rekindled briefly since in two 1971 singles, “Watching the River Flow” and “George Jackson,” the latter also revisiting Dylan’s fervor for protest songs.

Dylan’s stage presence was meanwhile confined to just four concert appearances between 1966 and the ’74 tour. Included were the 1968 Woody Guthrie tribute at Carnegie Hall, the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969, and two 1971 guest slots including George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh in August and The Band’s valedictory four-night stand at New York’s Academy of Music, where he joined them on New Year’s Eve on four songs. Dylan’s low profile contrasted with The Band’s concerts and festival appearances during that period. The Band was on hand for three of those four shows, with Harrison, Ringo Starr and Leon Russell supporting Dylan at the Bangladesh benefit.

By early 1973, Dylan was restless and ready to upend his routine. After a decade based in New York, he loosened ties to manager Albert Grossman and abandoned Woodstock for Malibu. He moved his recording deal west as well, leaving Columbia Records for a new deal with manager-turned-mogul David Geffen’s Asylum Records in West Hollywood, an hour’s drive from Dylan’s new beach digs. Stung by defection, Columbia cobbled together Dylan, an album of studio outtakes from 1970’s Self Portrait without any input from the titular artist.

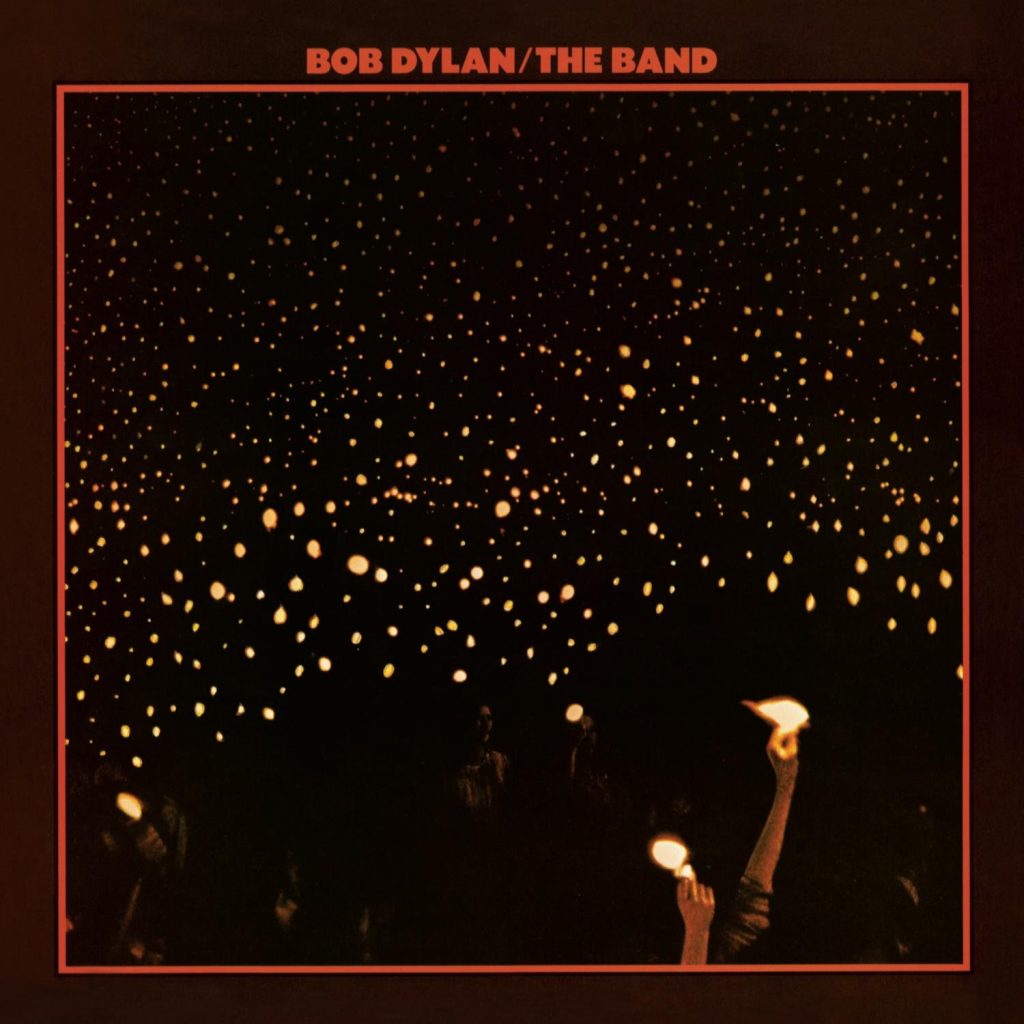

Any stain left by Columbia’s retaliatory LP was overshadowed by the unveiling of a double-barreled master plan hatched by Dylan and The Band’s Robbie Robertson in league with Geffen and concert promoter Bill Graham, highlighting the Dylan/Band collaboration on a new studio album, his Asylum debut, coinciding with a high-profile national tour. Over the summer, Robertson had followed Dylan west, with the rest of The Band joining them by fall, ready to get to work.

“Initially, the idea was that Bob was gonna do 10 or 12 dates,” Graham would later recall. “But everyone urged him to do more, because no one had really seen him in so long.” After identifying which markets would prove the best bets, Graham returned with a map and his proposal for 40 shows, “and God bless him, he said yes to everyone.” The six musicians left the details to Graham and began rehearsing daily at a Jewish boys’ camp in the Malibu mountains, working through as many as 80 songs over the course of several weeks.

The regimen also included 10 new Dylan songs earmarked for the studio. Heading to Village Records in West Los Angeles, they cut the set over six days in early November, with Dylan titling the set Planet Waves in honor of Saturn’s departure from his astrological chart—an exit he credited with “unblocking” his energies. Plans for his first live album were already baked into the ’74 career plan, with four cities targeted for recording, including New York, Seattle, Oakland and Los Angeles, where they would finish the circuit with three shows at the L.A. Forum.

As the tour launched, Dylan and The Band road-tested their sets, tweaking song choices and sequences. By the time they reached L.A., only “Forever Young” survived from Planet Waves, and while they continued to make room for some of Dylan’s deeper cuts, The Band’s sets had also been pared to the best-known material from their first three albums. In assembling tracks for the album, Dylan and Robertson wound up taking all but one selection from the final three shows in Los Angeles on February 13 and 14.

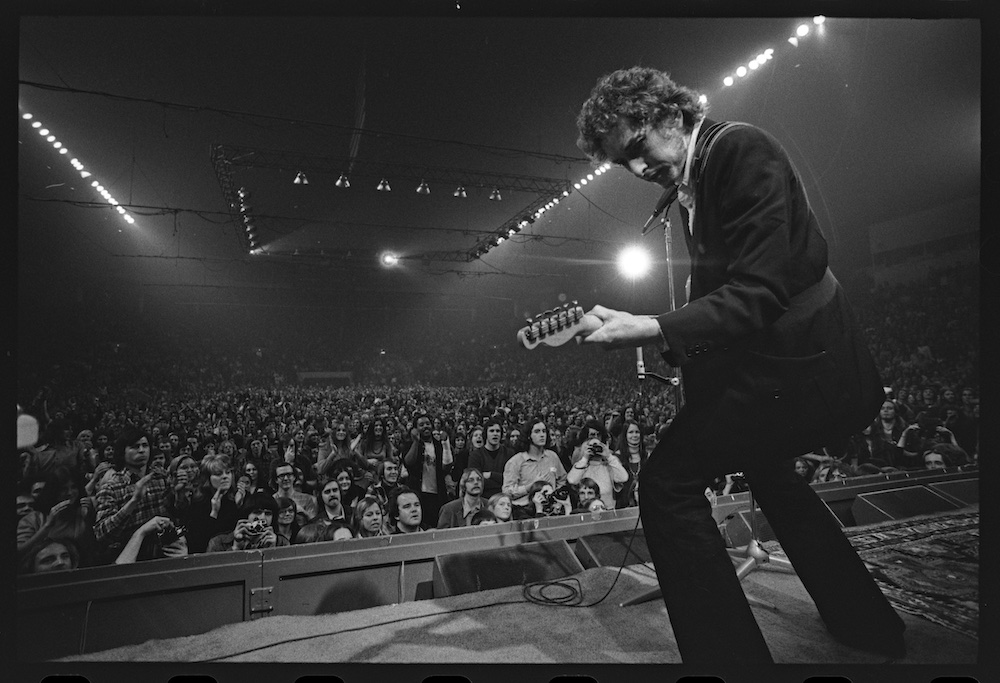

As reconstructed on Before the Flood, the tour kicks off with “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine),” one of Blonde on Blonde’s uptempo rockers, further toughened by The Band’s full-throttled arrangement, laced with Robertson’s stinging guitar solos and the galloping thrust of Levon Helm’s drums and Rick Danko’s bounding electric bass. Dylan matched their fury with a seething, half-bellowed vocal, equal parts scorn and delight as he discarded Nashville Skyline’s mellow croon to restore the rough edges of his earlier work.

The barnstorming momentum unleashed on the opener reflects how the six musicians had adapted to the tour’s cavernous venues and typically unforgiving acoustics. The Band’s nearly telepathic ensemble cohesion survives while their harder attack blunts the more nuanced playing heard on their 1972 live album, Rock of Ages, but Dylan’s aggressive vocals offset that trade-off. On “Lay Lady Lay,” he replaces the studio version’s come-hither languor with notable heat against Robertson’s sinewy solos and rhythm playing.

The combined group overhauls “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” recasting its studio approximation of a drunken Salvation Army band as a sleek, lively blues shuffle. Robertson gleefully tosses off crackling, voluble solos, Garth Hudson dials up a thicker, funkier texture on organ, and Richard Manuel adds gospel piano flourishes as Dylan grins his way through its surreal lyrics.

The one track pulled from earlier on the tour arrives in “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” recorded on January 30 at Madison Square Garden, energized by the sextet’s chemistry. The signature interplay between Robertson’s tremolo-spiked guitar accents and Garth Hudson’s keyboards underlines Dylan’s urgent lead vocal, with raw but righteous backing vocals from his bandmates adding further uplift.

The album’s sequence honors the concerts’ format, starting with an opening set with the full ensemble, followed by a set by The Band and a solo acoustic set from Dylan. Unlike Dylan, benefiting from his first official live record, the erstwhile Hawks face the unenviable task of competing with Rock of Ages, a set both musically and technically superior. Engineer Phil Ramone’s return for the Dylan dates couldn’t solve the rougher acoustics of the Garden or the Forum, while The Band’s ’74 takes on the same material betray wear and tear on their lead vocals since their Academy of Music stand.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Rock of Ages

One new Robertson song is proffered in “Endless Highway,” a road anthem taken at a nervous canter. Both pacing and lyrics mark the track as a companion to “Stage Fright” in its Sisyphean vision of a singer’s pilgrimage, a link reinforced by Danko’s querulous lead vocal on both songs, with the newer song’s weariness hinting at its author’s struggle with writer’s block at that point in the group’s lifespan.

Dylan’s solo segment rewarded his early fans with a compact set of unvarnished acoustic takes, including “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” and its darker cousin, “Just Like a Woman,” while giving both audience and his five Band mates a breather. For the album, the acoustic set was condensed further to just those two songs plus “It’s All Right Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

On record, the Dylan and Band concert builds toward its finale with a smart balancing act between adventure and nostalgia. The ghost of Jimi Hendrix presides over “All Along the Watchtower,” which embraces the firepower the late guitar wizard had harnessed in his thundering 1968 version without attempting to mimic his style; Robertson’s own indelible touch personalizes the Tour ’74 rendition.

From there, the six musicians draw a bead on Dylan’s legacy with hot-wired performances of “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Like a Rolling Stone,” his maximalist anthem, before climaxing with an emphatic electric reboot of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Dylan’s first signature song.

With its arena scale and emphasis on crowd-pleasers, Tour ’74 basked in its sense of occasion, setting up Before the Flood as the capstone to the strategy devised to restore Dylan’s prominence at the forefront of rock. The tour itself spanned just six weeks, with the live set mixed, mastered and released three months later. Both the tour and its album enjoyed critical rapture at the time, with Robert Christgau and Greil Marcus leading the parade of writers hailing the album as one of the greatest live sets ever. Planet Waves had already given Dylan his first album chart-topper, albeit briefly, with preorders earning gold album stature, yet subsequent sales only nudged the set to 600,000 copies. For Dylan, those numbers were a disappointment when contrasted with the tour’s massive box office draw and unfulfilled ticket demand. Platinum certification for the live set couldn’t offset his frustration.

He might also have harbored second thoughts about Geffen’s self-promotion around the Dylan signing: Having founded Asylum with a deep bench of singer-songwriters, Geffen flagged that success and Asylum’s graduation from boutique to major through its merger with Elektra Records by loading the deck for his January ’74 release schedule, dropping Planet Waves alongside Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark and Carly Simon’s Hotcakes. Overseas, Geffen had licensed Dylan’s releases to Island Records and its various distributors, a likely handicap after his prior reach through CBS International’s global network. Dissatisfied with how his Asylum releases fared, Dylan exited the deal and returned to Columbia with Blood on the Tracks, recorded that September and released in January 1975.

Over the half-century since, the critical luster for Dylan’s first live album has slightly dimmed, with the artist himself among its most dismissive critics. “I think I was playing a role on that tour,” he later told writer Cameron Crowe. “I was playing Bob Dylan and The Band was playing The Band. It was all sort of mindless.”

Beginning with his next tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue, Dylan evolved from crowd-pleaser to shapeshifting showman on long concert marches marked by experimentation and bold-faced collaborations. In hindsight, they ranged from triumphs to travesties, but his emphasis on live performance has inspired the unofficial Never-Ending Tour meme. His live discography has swelled with over a dozen major live albums, a massive multi-disc boxed set of the complete 1966 tour and extensive live coverage in his sprawling Bootleg Series. The Band’s work on Before the Flood has also paled against their substantial live catalog, bookended by Rock of Ages and the gala cinematic farewell of The Last Waltz concert gala in 1976.

Watch a rare (albeit rough quality), fan-made video from the 1974 St. Louis show

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024