A sophomore album that landed short of its goal but dodged an outright slump, Desperado saw the Eagles striving to burnish their hit debut’s success with gravitas, tethering their polished country-rock to a concept album driven by a Wild West narrative. But even before its release to more muted critical and commercial reception, the sequel’s creation masked stress fractures developing between the band, its producer, and its record company, as well as an internal power shift auguring future changes in style and personnel.

A sophomore album that landed short of its goal but dodged an outright slump, Desperado saw the Eagles striving to burnish their hit debut’s success with gravitas, tethering their polished country-rock to a concept album driven by a Wild West narrative. But even before its release to more muted critical and commercial reception, the sequel’s creation masked stress fractures developing between the band, its producer, and its record company, as well as an internal power shift auguring future changes in style and personnel.

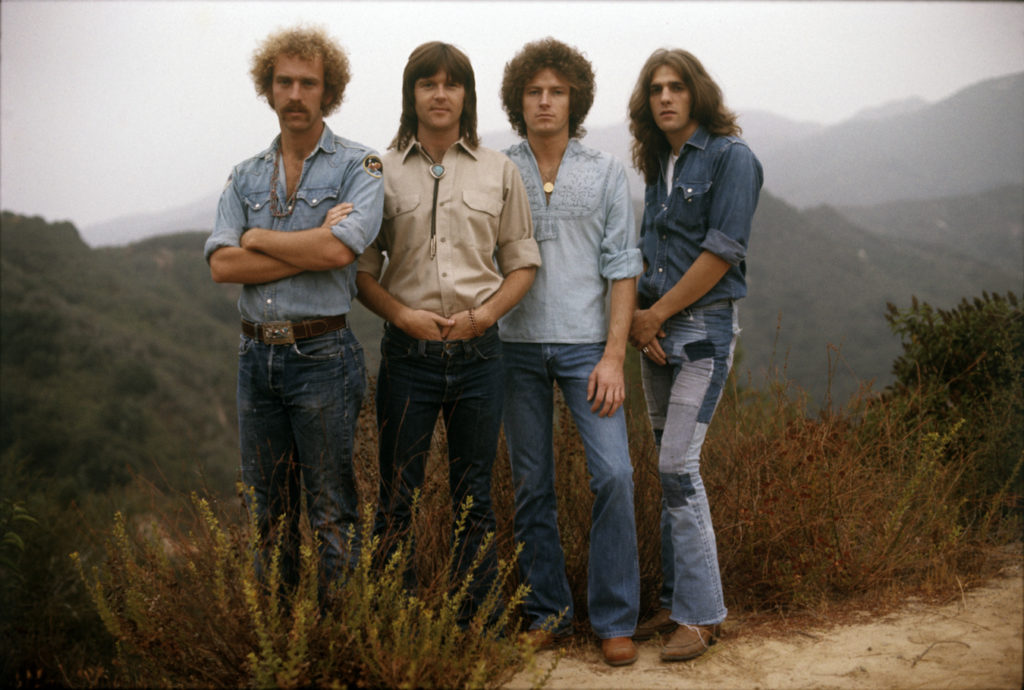

The quartet’s Laurel Canyon cred had been heralded out of the gate. Released in May 1972 a month before their full-length debut, “Take It Easy” was a breezy road song written by Jackson Browne with a lyric assist from Eagles guitarist Glenn Frey, whose laid-back lead vocal was cushioned by sleek harmonies and flecked by Bernie Leadon’s banjo. Multi-instrumentalist Leadon’s bona fides as a Flying Burrito Brother and bassist Randy Meisner’s credits with Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band and Poco reinforced the quartet’s country-rock pedigree, enhanced by their initial collaboration as Linda Ronstadt’s touring band.

That provenance fast-tracked David Geffen’s involvement. Signed to his powerhouse management firm with partner Elliot Roberts, they followed in the platinum footsteps of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young; as one of the first bands signed to Geffen’s boutique Asylum label, Eagles joined a roster built around singer-songwriters including Browne, Tom Waits, Judee Sill, J. D. Souther (Frey’s former partner in Longbranch Pennywhistle) and Ned Doheny, as well as Ronstadt herself.

Related: Read our Longbranch Pennywhistle Album Rewind

Geffen personally lobbied producer Glyn Johns, the British engineer who had leveraged sessions with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and numerous other U.K. artists to produce The Who and Steve Miller Band, among other clients. Johns initially passed but relented after Geffen’s persistence drew him to a rehearsal where the quartet’s vocal blend caught his ear: “There it was, the sound,” he would later recall in his memoir, Sound Man. “Extraordinary blend of voices, wonderful harmony sound, just stunning.” Johns had the band join him at London’s cutting-edge Olympic Studios to record in February 1972.

The band’s overlapping skill sets suggested a democratic partnership, as did songwriting credits. Frey, Leadon and Meisner contributed three songs each, including co-writes with other band members, Browne, and ex-Byrd Gene Clark, rounded out by a second Browne song and Jack Tempchin’s eventual Eagles evergreen, “Peaceful Easy Feeling.” Asylum’s aggressive push helped secure two top 20 single hits and propelled the LP to #22 on the album chart, adding commercial success to generally positive critical reviews.

Yet even as they completed their first tour, the band’s rookies, Glenn Frey and Don Henley, forged a bond that would begin to tilt the power dynamic. Success as lead vocalists on the album’s single hits reinforced alpha personalities and emboldened their ambitions to step up as writers. While Johns heard the band’s strengths as their lush vocal blend and their take on pioneering work by Rick Nelson, the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Poco, Detroit- born Frey and Texan Henley wanted to rock harder. Frey and Henley also had the closest ties to Asylum’s bunkhouse of signed singer-songwriters, which would directly influence Desperado’s conceptual ambitions.

Frey would trace the project’s cowboy cosplay to a jam session with Henley, Jackson Browne and J. D. Souther when they tossed around anti-heroes as the hook for a concept album. It was Browne, excited by the new duo’s first song, who pointed them toward the outlaw theme. With a maiden co-write in “Desperado,” Browne bolstered the tweak by showing them a book on gunfighters he’d received as a birthday gift from Ned Doheny.

Among its subjects were Oklahomans Bill Dalton and Bill Doolin, whose Doolin-Dalton gang was one of several tagged the Wild Bunch. Together, the four songwriters stitched together an opening song that would serve as the album’s narrative spine for their loosely inspired fable: “Doolin-Dalton” sets the stage for a climactic gunfight between its doomed outlaws, sung by Frey and Henley, and the lawmen closing in on them, leaning into grim wordplay on the chorus as they watch “duelin’…Doolin-Dalton” meet their fate.

Related: Our review of a 2021 Eagles concert

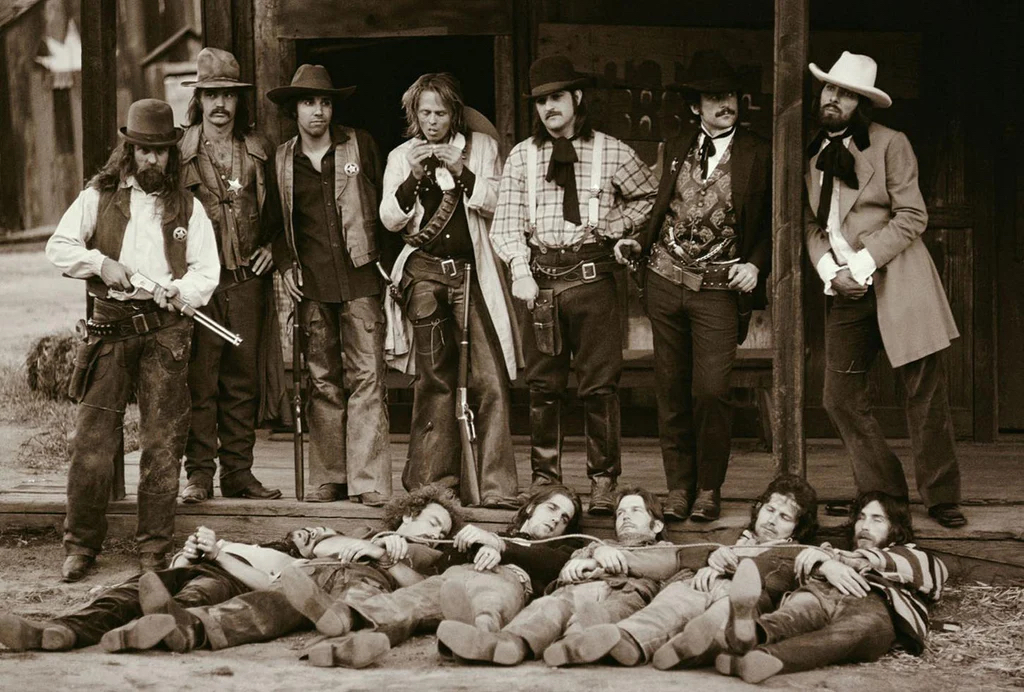

A strummed acoustic guitar answered by a forlorn harmonica figure opens the track, its foreboding reminiscent of Ennio Morricone’s scores for Sergio Leone’s hard-boiled westerns as Henley recounts the saga with a macho fatalism familiar to Leone and Sam Peckinpah fans. “Doolin-Dalton” will reappear as an instrumental interlude, then in a reprise that ends the album, with its central parallel between gun-toting outlaws and guitar-toting rockers underlined by the lure of “easy money and faithless women” and visualized on the album’s back cover.

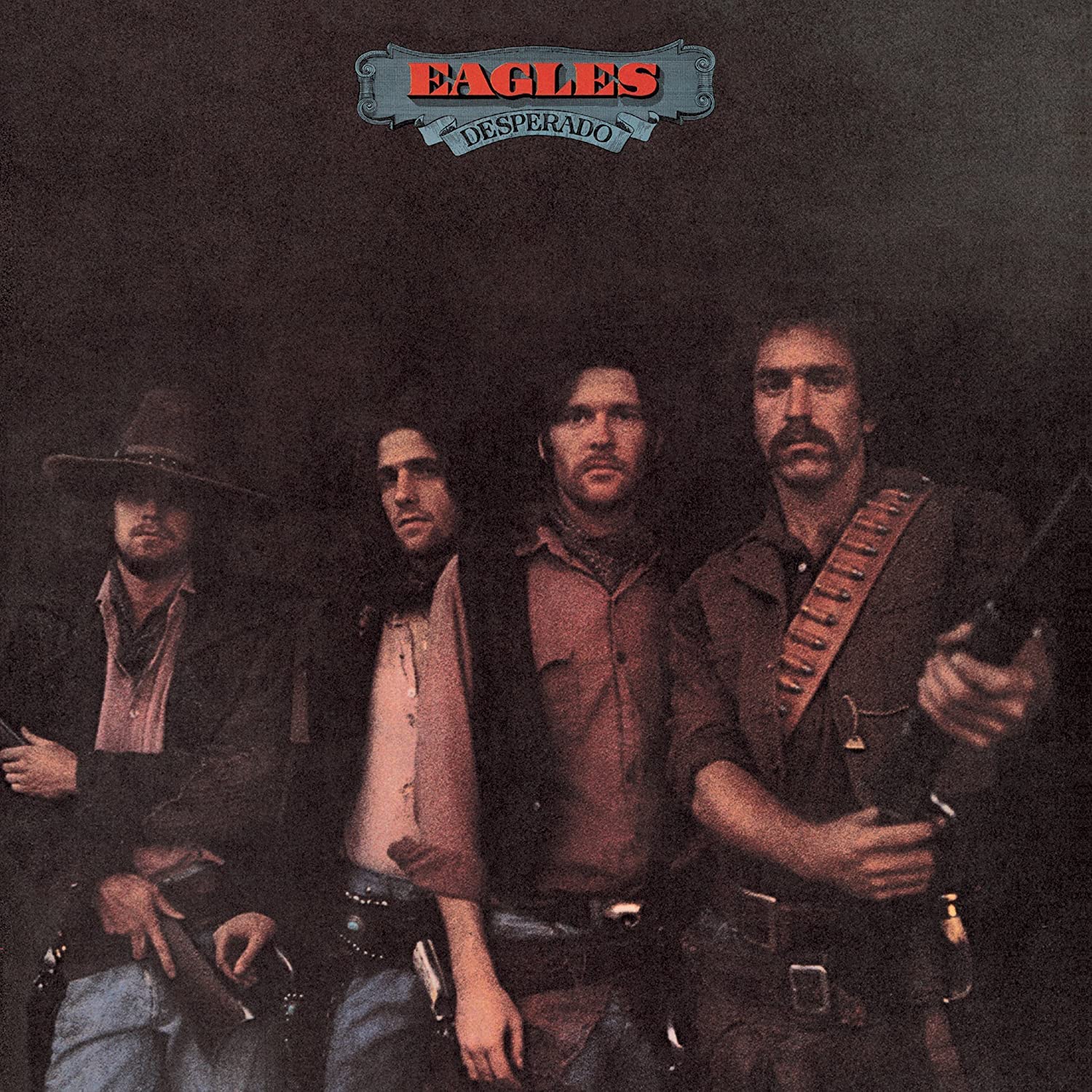

Staged at the old Paramount Ranch, a film set standing in Malibu Canyon, Henry Diltz’s sepia-tinged image depicts the four band members flanked by Browne and Souther as slain gang members lying at the feet of a posse enacted by management, road crew and producer Johns. The four Eagles left no doubt about the paradigm with their cover portrait in character, sporting gun belts, bandoliers, pistols and Leadon’s carbine.

[Henry Diltz’s iconic photos are available for purchase at the Morrison Hotel Gallery, which he co-founded.]

The rocker-as-outlaw premise is carried over with varying degrees of focus by game contributions from Leadon and Meisner. Leadon’s “Twenty-One” is a deep cut that has weathered well, thanks to his cheerful vocal and a lively arrangement showcasing his skill on both Dobro and banjo. The lyrics are an anthem to youth itself, bursting with naïve confidence, “young, fast as I can be” and carefree: “I can’t give the reason why, I should ever wanna die.” Leadon’s multi-instrumental prowess and the arrangement’s bluegrass accents qualify the track as the album’s most straightforward nod to country.

Meisner, meanwhile, dutifully fleshes out a gunslinger’s backstory in “A Certain Kind of Fool,” tracing the transformation of “a poor boy, raised in a small family” as he finds power in the feel of a gun “so shiny and smooth in his hand”—a passage to becoming “a certain kind of fool who likes to hear the sound of his own name.”

Where Leadon and Meisner were seasoned team players, the band’s two alpha members were willing to stray further from their own organizing concept. Frey’s eagerness to inject a harder rock thrust to the band is given free rein on “Out of Control,” which sets aside the acoustic instruments and billowing vocal harmonies to flex squalling electric guitars and Henley’s pummeling drumming. Apart from its exhortation to “saddle up, boys, we’re gonna ride into town,” the track, written by Frey and Henley with road manager Tom Nixon, relaxes sagebrush and six-shooter imagery to offer a celebratory call to party that touched on one of Frey’s bones of contention with Glyn Johns. The producer had enforced a ban on drugs and drink during the sessions, a discipline at which Frey had balked while they were tracking at London’s Island Studios.

Frey and Henley ventured even further from Desperado’s organizing theme with “Tequila Sunrise,” one of their earliest collaborations, which taps into a wry romanticism that would become a signature. As they would in subsequent songs written together, as well as with frequent collaborator J. D. Souther, they alternated between romantic poles of devotion and betrayal, the latter plumbed here as Frey laments the heartbreak of “another lonely boy in town” pining for a woman “out runnin’ around.” The song would be issued as a single concurrent with the album’s release, foreshadowing its disappointing sales after peaking at #64, far below the debut album’s seven-inch issues.

Watch Eagles perform “Tequila Sunrise” live

The album’s title song (and trigger for Browne’s Wild West suggestion) was the product of the duo’s first writing session in Henley’s Laurel Canyon home after returning from London to record the debut album, building on the fragments of a song he had started writing years before. Henley would later recall that Frey “leapt right on it—filled in the blanks and brought structure.” Jackson Browne would cite the song as pivotal to the album’s evolution from a broader canvass of antiheroes to its final western outlaw theme; in crafting “Doolin-Dalton,” Browne, Frey, Henley and Souther” would echo the “queen of diamonds” poker metaphor set forth in “Desperado.”

Eagles’ ties to Geffen and Asylum extended beyond Browne and Souther, with Linda Ronstadt bringing added exposure through her cover of the title song and singer-songwriter David Blue contributing “Outlaw Man,” a four-square rocker which fit snugly with the concept in lyric content. Born David Cohen, Blue was a veteran of the Greenwich Village folk music scene of the early ’60s who had recorded for Elektra and Reprise before signing with Asylum, a Bleecker Street denizen now welcomed by the habitués of the Troubadour’s bar in West Hollywood. The song provided a ready-made second single.

As their partnership coalesced, Frey and Henley began exerting their influence both inside and outside the Eagles, increasingly chafing at their key business ties. As their record company chief, David Geffen had offset his initial value as a manager by countermanding some of the band’s fiscal and creative demands, killing a foldout poster for an already lavish gatefold debut album jacket, then capping the recording budget for Desperado at a still robust $75,000 after the debut’s lofty price tag of $125,000. Grumbling continued as they headed out to tour behind the second album, unhappy with the album’s disappointing sales and radio performance, while the rock press was divided this time out.

Desperado, released on April 17, 1973, would be the last Asylum album distributed through Atlantic. Asylum’s merger with Elektra Records that October pulled David Geffen’s focus further to the label side as he stepped up to manage an enterprise that had expanded dramatically in staff, artist roster and stylistic diversity. The Asylum roster that Geffen had once vowed would never outgrow his sauna room or diverge from its clique of singer-songwriters would be given preferential treatment under Geffen’s two-year tenure, to the dismay of orphaned Elektra acts, a bias lost on the Eagles, who recognized the conflict of interest that had been festering for artists signed to both Geffen-Roberts and Asylum Records.

As they began work on the next album, Frey and Henley consolidated their leadership and broke off their relationship with Johns, scrapping all but two tracks—among them the band’s first #1 single, “The Best of My Love.” Having become familiar with America’s country-rock vanguard while working with the Stones and encountering a genre pathfinder named Gram Parsons, the English engineer and producer was more committed to the style than Frey and Henley, for whom Eagles’ initial country-rock was more a marriage of convenience than a matter of conviction.

Regrouping back in L.A., Eagles would complete On the Border, accelerating their turn toward higher-octane rock with the addition a new lead guitarist, Don Felder, while jolting David Geffen in both his roles by their defection to a new manager, a shrewd and aggressive fireplug who had joined Geffen-Roberts, assessed the Eagles’ checkered ties to Geffen and left the company, taking the band with him. From that point forward, Irving Azoff guided the group on its steady ascent to ever greater success, rewarding Asylum with one of its biggest moneymakers while perfecting the science of squeaky-wheel manager-label relations.

Eagles would never completely abandon country elements in their music, which survived in Frey and Henley’s gentler romantic ballads, but their profile as country-rock exemplars would become secondary to the platinum ambitions carrying them from their scuffling days at the Troubadour and the Palomino to headlining stadiums. By the time they fractured in 1980, disbanding for 14 years, their stature as one of the ’70s’ definitive mainstream rock outfits was secured.

Watch the band perform “Desperado” live

The Eagles’ catalog, including Desperado, as well as a 2024 collection, To The Limit, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

3 Comments

Great artistic and “market” analysis. The Eagles’ Poco lineage was handy, shallow and short lived despite the additional of Timothy B. Schmit. Thanks!

Great review and information about what for me is my absolute favorite concept album in all of Rock & Roll. I can remember watching an interview with Don Henley when he turned away from the idea that the Desperado album was a concept album and I thought at the time, who is he kidding? Well, by design or not, every song ties in with the western theme, outlaws, loneliness, and loss. To combine that many great songs together in one album is beyond remarkable and I honestly do not have a favorite. I just play the entire album when I am in the mood for some great music and some classic lyrics. Desperado is an album for the ages.

I have always wondered why no one turned “Desperado” into a film or even a Broadway show. The songs are certainly there, and there’s a story narrative as well. Come on, Hollywood and Broadway: how about it?