Producer and engineer Eddie Kramer boasts one of the most impressive résumés in rock, having worked with everyone from the Rolling Stones to Led Zeppelin to Kiss. But to many, it’s his work with Jimi Hendrix, beginning with his engineering on the 1967 debut album Are You Experienced, that still tops his list of credits.

Veteran music journalist Harvey Kubernik, author of the 2021 book Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child, has conducted several interviews with Kramer over the past 25 years, initially published in edited versions in the now-defunct U.K. music weekly Melody Maker and THC Expose magazine, as well as several periodicals, including Record Collector News magazine and HITS magazine, but never exhibited online. Many of the dialogues subsequently appeared in severely truncated form in Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child.

With the arrival of a recent, previously unreleased live Hendrix collection—Los Angeles Forum, April 26, 1969—, Best Classic Bands presents excerpts from some of those interviews.

Eddie Kramer Remembers Jimi Hendrix

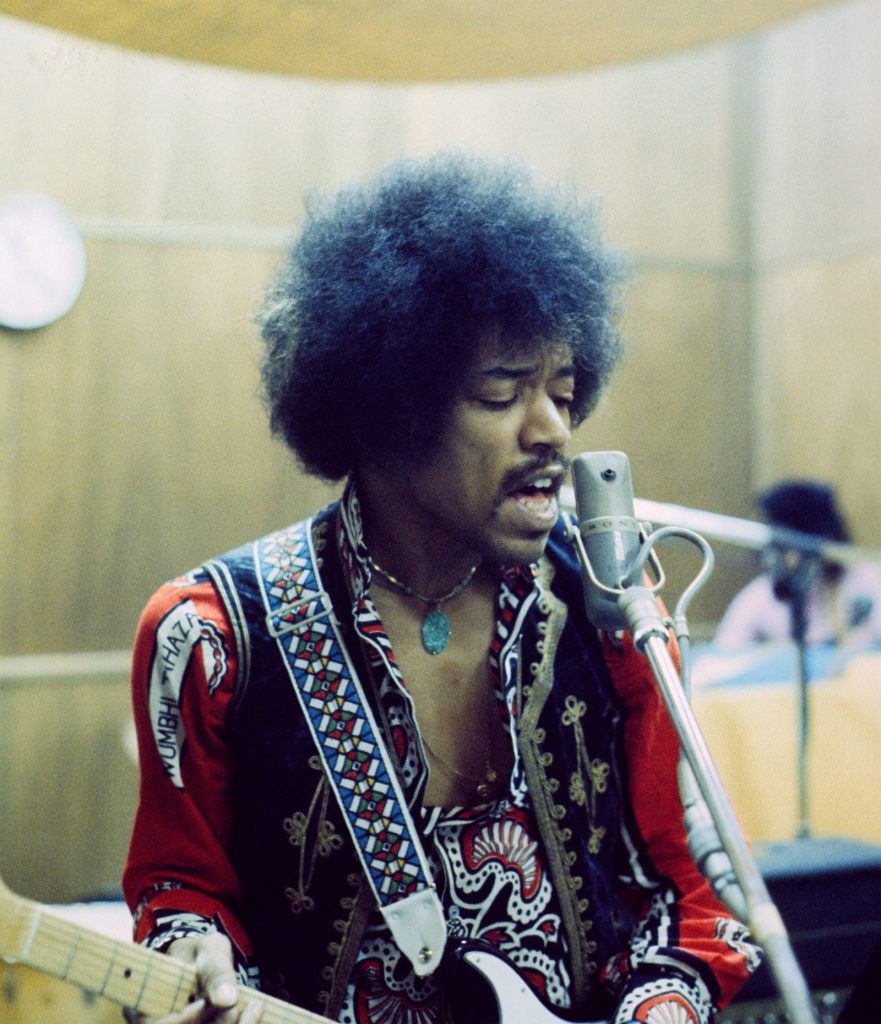

I was very fortunate to work with James Marshall Hendrix. He changed my life and many other people’s lives. He was the greatest. It was, obviously, a very intense four-year period. I started with Jimi in January of 1967. I wasn’t there for everything, unfortunately, but I was there for the majority. I always ended up mixing everything of Jimi that was recorded live, including Band of Gypsys. He was fascinated with the recording process, whether it was live or in the studio. His fascination and interest was very deep. We worked very closely together and when it came time to mix any live material we would sit together and work on it if we could.

Related: Hendrix in his Greenwich Village days

There was this amazing dynamic all rolled up into one human being, an amazing purity and presence. Whenever Jimi walked into a room, you had to turn your head, because you felt you were in the presence of something quite unusual. And he had this way of commanding attention without commanding attention. His demeanor was so shy and self-effacing. He just sat there in a corner but people were attracted to him. It’s like magnetism. You have that aspect, the shy, wonderful, soft-spoken human being who, at the turn of a switch, as soon as he got on stage, became this otherworldly being who could unleash gobs of power and lighting bolts at you. I think that’s one aspect.

Then you dive into all the other aspects, which, of course include the music, this synergy, or synthesis if you will, of all of the bits and pieces of information that had flooded his brain. His sponge-like brain would take everything in, with no filtering, and probably would sit there for a day or two or three or a month or a year or whatever, and out of it would come a song. It’s a unique thing

When you look back at how he first started to write songs, with [early manager] Chas Chandler’s encouragement, he absorbed so much. And, the surprising thing is that the music is so pure and so flamboyant and descriptive; it conjures up imagery that I feel very few rock artists have come close to: the passion and the emotion and the bareness of it. Listen to “Voodoo Child,” for God’s sake!

I’m always learning stuff about Jimi: the backstage stuff, the behind-the-scenes stuff. The documentaries just fill in the gaps. It’s fascinating: Hendrix and his music, the songs, the lyrics, the playing, the sound, the sheer impact of him as an individual will last forever.

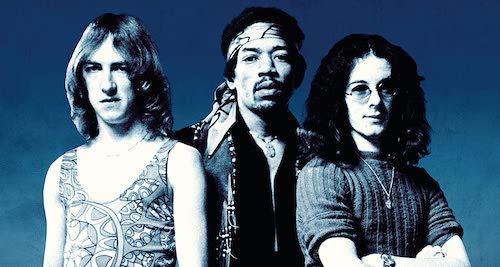

Kramer on Hendrix’s Band Members

I think [bassist] Noel [Redding] has been much maligned. His playing and his understanding of what it took to support Jimi was remarkable. We all know about their personality differences, and there were plenty. But musically, I think Noel is very underrated and did a tremendous job. Mitch Mitchell, being the ex-jazz drummer, was the perfect foil for Jimi. I don’t think any other drummer kept up with him. One can make a case for Buddy Miles being the best fatback drummer, which he was, able to keep a tremendously steady beat, which he did, ridiculously, but Mitch was the little known genius who just sort of fiddled around the kit and did the most spectacular thing that would spark Jimi’s imagination. He was able to stay with Jimi and always land on the downbeat, even though he would do the most outrageous fills. You’d think, “There’s no way in hell he’s gonna land on 1,” but he did.

Kramer on the Band of Gypsys Album

I didn’t record it. I did all the mixing subsequently. After the four shows, the pressure was on us to deliver the record. I seem to remember Jimi and I started sifting and mixing the multi-track recordings at Juggy Sound in New York. January 1970. Imagine Jimi and I sitting at the board when we mixed. He knew what he wanted and cherry-picked what songs he wanted. And then we assembled it and started mixing.

During the mixing, there is one moment I will always remember because it points to what happens afterwards. Jimi is listening and here goes Buddy [Miles], launching into one of his long vocal jams, if you will, scatting and doing his thing. Jimi puts his head in his hands, his hat dipped down, and he’s on the console, and I could hear him say, “Aw…I wish Buddy would shut the fuck up.” And it points to what happened later, because we all know the Band of Gypsys is short-lived.

It served its purpose. It had dramatic impact, of course, for many years to come. It’s part of Jimi’s arsenal of great songs, great performances, very R&B-based, very funky. It showed the new shift. It showed the direction he was going in. And then he re-forms the Experience but with a “newly minted Mitch Mitchell.” And I say that in quotes because Mitch has obviously been seriously looking at the shift and he has adopted and adapted some of Buddy Miles’ technique.

Kramer on Hendrix’s Performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival

I got to work on the entire Monterey movie (The Complete Monterey Pop Festival/The Criterion Collection). One of the advantages of modern technology is that you can fix things that you were not able to fix many years ago. It’s so sophisticated now that you can actually remove serious crackles, bangs and pops. We were able to use the one Otis Redding track that had never been mixed correctly before, and the whole thing sounded so much better when it came time for Jimi’s stuff at Monterey. There was a serious bad noise that had nothing to do with the music and I could get rid of it without affecting the music. So that whole experience was a challenging one but an interesting one.

But what was cool was to see all those 1967 tapes from Monterey all stacked up in the control room. You realize the enormity of the music that was just before you: the Mamas and the Papas, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar. Monterey is about that wonderful historical moment, not only for Jimi Hendrix but also for Janis Joplin, who was essentially discovered there. The way I think of Monterey was that this was [Hendrix’s] premiere shot. He knew this was his one opportunity to make a big splash and he did. At Monterey, he was in the mindset that he had to seriously kick everybody’s butt: “I am going to pull out every stop I have learned,” with the sweeping of the hand up and down the neck, between the legs, behind the back. All that stuff was absolutely executed with a fire, passion and urgency that comes across in the movie. You can tell that he is saying to the world. “Look. I’m here. I’m Jimi Hendrix. And I’m gonna kick your ass. And you better take note of me.” Look at the way he is dressed. Look at the way he is talking to the audience. He’s so up and part of it. It is the most stunning performance. It is fantastic. It will live on.

Listen to “I Don’t Live Today” from the 2022 release Los Angeles Forum, April 26, 1969

1 Comment

I gotta say these is the most interesting first-person accounts about Jimi that I’ve ever read. And it doesn’t surprise me that it come from Eddie Kramer. As perhaps the only living gatekeeper to what happened behind the scenes during Hendrix’s tumultuous and too-short career, this is exactly what Kramer should be doing, in acting as a curator of sorts to this amazing pioneer’s legacy. So much is written about Hendrix’s guitar playing, his performances, his flamboyancy. etc… But beyond all the superficial physical aspects of his fame, his real genius was, as Kramer points out, in his mind. And this was expressed nowhere better than through the sonic mastery of his actual Hendrix-released recordings. No one will ever argue about Jimi’s masterful guitar playing. But it was what he thought to play and in the way he created symphonic musical labyrinths with his guitar part in making ground-breaking sounds that sets him apart from any other “guitar player” on the planet, then or now. I know many will disagree with me, but, in my opinion, that’s why Hendrix’s live stuff is so one-dimensional, and somewhat boring, as it’s pretty much limited to the physical, instead of mind-blowing imagination, where he just used the guitar, and its electronics, as tools to express his amazing musical visions which he could never really do justice to live.

I was also thrilled to read someone give the credit they so richly deserve to Mitch Mitchell (such an interesting perspective on Mitch’s change in styles to accommodate Jimi’s musical evolutions), and particularly to Noel Redding, who, for some reason, has always seemed to have been cast as either the bad band member, or of no particular consequence. Meaning no disrespect to Billy Cox, who gets more than his deserved share of limelight and credit in Hendrix’s legacy, but Cox’s straight ahead bass lines (which worked for what Jimi was doing with him at the time) couldn’t touch the amazing and innovative bass parts (not to mention his signature backup vocal sounds) that Redding played on the three core Hendrix studio LPs. I doubt there was anyone who could have backed Hendrix better. Redding and Mitchell were integral musical components of the Experience — not just some anonymous backup musicians whom anyone could have been.

I’ve been pretty critical of Eddie Kramer on these pages, in any previous article relating to Hendrix, and deservedly so. For while he may not have owned the rights to every piece of tape that Jimi may have farted on, he has been actively complicit with Hendrix’s sister in pirating Jimi’s legacy and releasing rehearsal and song-writing recordings that Jimi never intended the public to hear as “new Hendrix releases.” The even more maddening aspect of this is that Kramer’s very participation gives the release of this material a sort of authenticity, or stamp of Hendrix approval, if you will, which based on any reports of Hendrix’s reputed perfectionism, to which Kramer was a first-person witness, Hendrix would never have allowed these types of work in progress recordings to be heard by the public. While Janie Hendrix’s greed has betrayed the legacy of a brother that she was too young to even know, in my view, Kramer active participation makes him Jimi’s more personal Judas, who sold him out for forty pieces of silver. It’s heartening that he can still remember who Jimi actually was (since he claims Jimi changed his life and all), and the greatness that was The Experience.