Toward the end of the 1960s, popular music broadened its borders, as artists experimented with expansive approaches that ranged from the portentous to the absurd. The Beatles were in the midst of a remarkable progression into ever-headier territory, and paved the way toward meshing complicated arrangements with grand orchestration when they shifted focus to studio work with 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The richness of their ideas in that period outlined concepts that became foundations for entirely new approaches, not least among them the music of their English countrymen the Electric Light Orchestra, who leapt from a springboard of inspiration into a singular body of work.

Toward the end of the 1960s, popular music broadened its borders, as artists experimented with expansive approaches that ranged from the portentous to the absurd. The Beatles were in the midst of a remarkable progression into ever-headier territory, and paved the way toward meshing complicated arrangements with grand orchestration when they shifted focus to studio work with 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The richness of their ideas in that period outlined concepts that became foundations for entirely new approaches, not least among them the music of their English countrymen the Electric Light Orchestra, who leapt from a springboard of inspiration into a singular body of work.

By 1973, after three years, as many albums and some commercial headway, Electric Light Orchestra (who had just done away with the article preceding its name for its latest record, and would usually be dubbed ELO for short) remained a work in progress. On the Third Day was the band’s first without founder (and driver of its initial vision from his days spearheading the rock/classical fusion act The Move) Roy Wood, leaving co-founder Jeff Lynne clearly in charge of the group’s creative output. Its lineup saw multiple changes in its early years, but there clearly was something there, with a U.K. top 10 emerging from each of its first two albums (“10538 Overture” and a blustery interpretation of “Roll Over Beethoven” that also marked the band’s first appearance on the U.S. singles charts, peaking at #42) before its most recent yielded the U.K. #12, U.S. #53 “Showdown.”

Related: In this interview with ELO’s Bev Bevan, he explains the band’s evolution from The Move

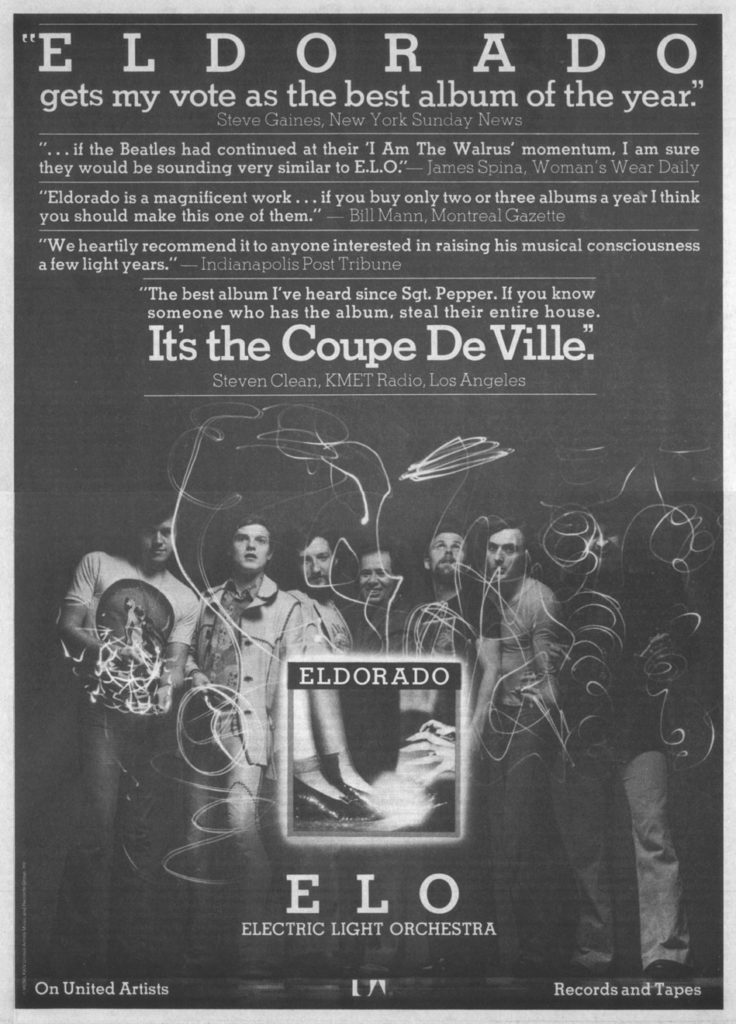

For ELO’s fourth record, Lynne made an important refinement. Where preceding records had built orchestral sections with overdubs, Lynne opted to live up to the band’s name when he hired Louis Clark as string arranger and utilized a full orchestra in the group’s recordings. That approach paid immediate dividends with Eldorado, the ambitious September 1974 release that enhanced the group’s popularity worldwide and refined an approach that would bear fruit for years to come.

For ELO’s fourth record, Lynne made an important refinement. Where preceding records had built orchestral sections with overdubs, Lynne opted to live up to the band’s name when he hired Louis Clark as string arranger and utilized a full orchestra in the group’s recordings. That approach paid immediate dividends with Eldorado, the ambitious September 1974 release that enhanced the group’s popularity worldwide and refined an approach that would bear fruit for years to come.

Although the use of a full orchestra meant there was less assembly required, Eldorado quickly established that ELO’s meticulous musical structuring was not going anywhere. The album-opening “Eldorado Overture” is a triumph of organization, in which a slow, airy shimmer builds to a dramatic scene-set.

Listen to “Eldorado Overture”

Peter Forbes-Robertson delivers a just-overdone spoken-word introduction that ends with his voice bouncing between channels, opening a gateway through which an array of plump strings and timpani ascend before giving way to a string-bed sprint draped with cymbal crashes that highlights the 30-person orchestra’s robustness.

Tied together thematically as an everyday-guy narrator’s dreams, Eldorado is a concept record sonically as much as it is thematically; as much as its dreamer’s musings form a thread, the record derives greater unity from its extensive sonic connective tissue. “Eldorado Overture” flows seamlessly into a landmark of production balance, the mellow “Can’t Get It Out of My Head.” Paced by Bev Bevan’s soft drum rattle and light cymbal taps, Moog swatches from Lynne and Richard Tandy, rich orchestration atop which the cellos of Michael Edwards and Hugh McDowell float, and a well of vocals (from a full chorus also employed in album sessions), it yields density without disorder in a generally straightforward, sweet-hooked pop-rock ballad.

Listen to “Can’t Get it Out of My Head”

As the album’s first single that November, it didn’t make the U.K. charts, but internationally it was a different story. It climbed as high as #9 on the Billboard singles chart, easily the band’s biggest stateside hit to that point, and one of seven times in the next decade an ELO single would reach the top 10 in the U.S.

For all the grandeur of Eldorado’s design, it is less an example of prog-rock than kitchen-sink pop, where disparate high-concept pieces are sewn together painstakingly into a design in which what they’re saying frequently matters less than how they are saying it. Ostensibly an antiwar song framed as the story of a reticent Middle Ages military hero, in “Boy Blue” the real point is in the atmosphere, from an opening brass fanfare that dissolves into a fluttery Minimoog interlude with slowed vocals haunting the background.

Listen to “Boy Blue”

Bassist Mike de Albuquerque makes an appearance in the song, which would prove his last with the group when he left during recording. Lynne’s treated vocals coalesce nicely with Tandy’s in the refrain, nestled into a whole that is thick yet airy, and shows itself as the work of musicians who carefully consumed latter-day Beatles records and turned their concepts into something else entirely.

“Laredo Tornado” relies on guitars more than most ELO numbers, opening as full-bore rock with grinding electric dressing, and then developing into a simmering churn with gritty Moog slipping into the listener’s right ear.

Full-bodied as it may be, at its heart it is a pop song with cello flourishes. The tune that follows, the Robin Hood fantasy “Poor Boy (The Greenwood),” is built around a skillful balancing act, with the orchestra and chorus providing sturdy atmosphere and a sense of formality to accentuate the chugging pace and curious turns of an ever-changing sonic tapestry.

Listen to “Laredo Tornado”

The tune, which would reappear as a B-side for “Telephone Line” in 1977, swells and builds to a driving, definitive finish that marks a notable break in the album’s sequence, and on an album of otherwise continuous motion sticks out like a sore thumb today, a reminder that it served to cap a vinyl side in the original album-based design.

Listen to “Poor Boy”

Side two opens with “Mister Kingdom,” whose debt to the Beatles might be just a little too pronounced, close as it comes to the melody and character of “Across the Universe.”

Listen to “Mister Kingdom”

Tandy’s Wurlitzer piano trickles across its gusty, rambling atmospherics, as Lynne’s matter-of-fact singing nestles atop the symphonic flourishes that color its spacey pulsation. It throbs to a close, and then turns on a dime to a formal interlude at the head of “Nobody’s Child,” which soon transforms again into a slinky blues.

Listen to “Nobody’s Child”

Responding to a hearty rhythmic chant of, “painted lady,” Lynne coolly infuses character into the lyrics alongside a deliberate piano bounce. Along the way come swaths of horns, decorative strings and an amusingly arch chorus moan within a spacious churn, coloring a song that keeps changing direction while always moving forward.

“Nobody’s Child” never really finishes its business, as it crashes abruptly into the throwback rock chug of “Illusions in G Major,” a lively romp akin to what one might have expected had Chuck Berry worked in a spaceship.

Listen to “Illusions in G Major”

With insistent layered vocals that would always be part of ELO’s signature sound, its horn-draped propulsion makes for an ebullient, rollicking cross-pollination of past and future that lands in the present in a timeless manner.

The thematic journey concludes with the silky title track, a strong example of an ELO song that is more than the sum of its parts.

Listen to the album’s title track

Lynne’s vocal is earnest while matching the song’s easygoing dreamy elegance to keep its storytelling grounded despite its more elaborate flourishes, combining technology and refined personality in a carefully manicured, purely digestible array. When it gives way to the “Eldorado Finale,” it marks a big finish earned at the end of a journey, a trip across the breadth of ELO’s sonic palette with all the parts tossed carefully into a large stew.

Listen: And finally, “Eldorado Finale”

Eldorado climbed as high as #16 on the U.S. album chart, and the band made the most of the door it opened, reeling off four straight albums that reached #8 or higher. First among them was 1975’s Face the Music, which would boil down Eldorado’s orchestral ambitions into an even more chart-friendly approach, exemplified by the worldwide hit “Evil Woman.” The road to that success was charted from the lessons of Eldorado, where, with Lynne leading the way as its producer and primary songwriter, ELO moved past the uncertainties of its early years and took listeners on a journey into the future.

Watch ELO performing live on The Midnight Special in 1974

7 Comments

Thanks for the wonderful article. For historical accuracy, Roy Wood left the band after recording the first album, 1971’s Electric Light Orchestra, also known as No Answer in the U.S. ELO was Jeff Lynne’s baby from the second album, 1973’s Electric Light Orchestra II.

Matt… Although Roy Wood isn’t credited on the ELO II LP – I just double-checked my own vinyl copy – our understanding is that he did perform on a few of its tracks.

Yes, Roy may have provided an instrumental assist on ELO II (thanks Roy), but starting with the same album, ELO was Jeff’s baby “creatively” as he wrote all songs (minus Rollover) and exclusively produced. One could imagine what ELO II might have sounded like if Roy was still a creative partner. The point is that the creative shift did not start with On The Third Day.

Anyway, it’s a minor quibble. Thanks for giving Eldorado some deserved love. It’s quite a musical accomplishment.

Roy contributed instrumentally to two songs in the second album, the two “Boogies.”

Sure would have been nice to see/hear the musical excerpts. You didn’t bother uploading them to Canada. Again. Bet you will not publish this comment – again. So disappointing. I love your newsletter otherwise.

Sorry to hear that, Lucy. BCB can’t control what countries YT allows clips to be seen/heard. For studio recordings, BCB goes out of its way to use the artists’ and labels’ official uploads.

Mik Kaminski also contributed violin to the album “Eldorado”.