It’s November 1971, and Elton John is everywhere. Three of his albums have appeared in U.S. record stores within the current calendar year, and as the year winds down, another arrives. Madman Across the Water is the boldest of the lot, seeking to be all things to all listeners as a display of confidence rather than overreach.

It’s November 1971, and Elton John is everywhere. Three of his albums have appeared in U.S. record stores within the current calendar year, and as the year winds down, another arrives. Madman Across the Water is the boldest of the lot, seeking to be all things to all listeners as a display of confidence rather than overreach.

John’s eponymous second album (and stateside debut) was a substantial success a year earlier, followed in Europe by the country-leaning—and less commercial—Tumbleweed Connection, which would not reach the Atlantic’s west side for several months.

The soundtrack Friends fulfilled a pre-breakthrough commitment and soon disappeared, and the live set 11-17-70 tried to grab a piece of the action bootleggers were getting with copies of the show’s initial radio broadcast. Three records, but none offering a real follow-through on his initial commercial success. Easy as it might be to justify in that context, a fourth album was a lot to ask the marketplace to digest, let alone support.

Madman reset what had become a scattershot career path. Packed with personality and infectious melodic energy, it expanded the variety and ambition of John’s material with complicated, bravura compositions unlike what anyone else offered, establishing the singular sonic identity that would become a trademark Elton John calling card for years to come.

Madman takes no chances with the listener’s affections; it isn’t two bars old when its first irresistible moment arrives, in the fluid piano trickle that lays the groundwork for “Tiny Dancer.” Welcoming and airy, it is a seminal pop contrivance, and the album’s greatest achievement. Gus Dudgeon’s production (with an arrangement by Paul Buckmaster) tastefully mixes the homespun with the formal, initially combining pop and country in a manner decades ahead of its time. The string section that emerges near the three-minute mark adds to that mix as it propels the song’s hook, a potent complement to the ascending drama of John’s piano line, and the final building block of an ingenious, gorgeous sonic assembly. The song fully defines John’s vocal prowess: lively, full of character and naturally theatrical, but not in a way that overpowers any moment. Levelheaded or outlandish, he is always convincing.

Watch the official video created for “Tiny Dancer” in 2017

Enticing as its structure may be, its stature owes at least as much to lyricist Bernie Taupin. One of the best pieces ever written about life inside the music industry, it seamlessly combines romance and everyday charm. Full of details John sells with brio, it captures life on the road more evocatively in just over six minutes than Almost Famous did in a full-length film. “Tiny Dancer” represents the best of the John-Taupin partnership: lyrics built for enthusiastic delivery, and a performance that knocks them into the cheap seats. John is dynamite, Taupin his all-important fuse.

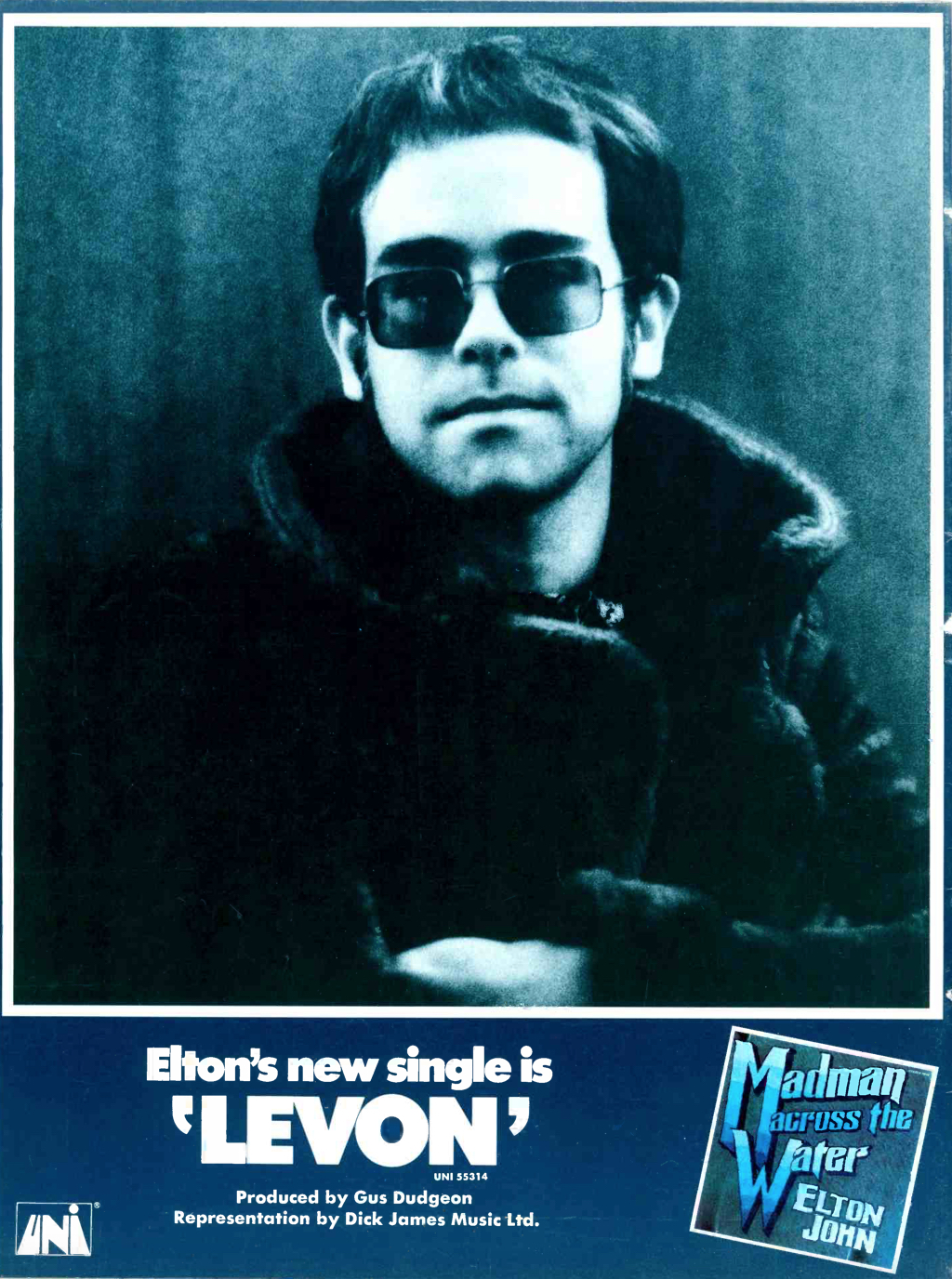

Despite its more fanciful nature, “Levon” shares similar qualities, starting with an inviting piano opening that heralds a rich melodic backdrop. John rides a grand, swelling chorus hook to its peak, still telling a story even when he’s shouting. The song would be a catchy, conventional rock number were its close powered by a guitar solo, but strings make for a more robust set piece, adding gravity and drama.

Related: “Levon”… How the song came to be

Anyone can cover “Tiny Dancer”—the composition possesses a universal appeal any competent vocalist can wrangle with appropriate conviction. “Levon,” on the other hand, is signature work. Offbeat and more than a little peculiar, the story of a balloon salesman and the son who wants out of their shared life requires someone who can handle the surreal with conviction, a quality John possesses in spades. Any cover is more echo than interpretation; everybody can tell that this is his song.

The earnest “Razor Face” seems straightforward enough, alloying electric guitar with a guest organ turn by Rick Wakeman to form a rock backbone, but it’s a restless piece. Toward its end, an unheralded accordion lands front and center for an extended solo, trading licks with an electric guitar through the playout. It’s an odd sort of sonic urgency, more like noodling than cohesive design.

The A-side closes with the title track, which nearly exceeds its boundaries. Its synthesizer-fattened design is something of a sonic yard sale, but orderly—not so much cluttered as intentionally overloaded. Almost too subtle to fit in, yet still decorative, is acoustic guitar gilding provided by Davey Johnstone, appearing on his first project with John in what would become a long and fruitful collaboration.

The set’s longest song, “Indian Sunset,” would be a more difficult sale today: a first-person narrative of a Native American staring down the end of his time. Forged with blustery sincerity and a touch of clunky imagery, there is nevertheless richness to its theatrical contemplations, fueling a social consciousness exercise appropriate to its time.

Related: Elton’s 11-17-70 was a signpost of things to come

“Holiday Inn” is a considerably less effective look at life on the road than “Tiny Dancer,” an odd lament of banality despite nice touches. Johnstone’s fluttering mandolin adorns a robust, string-trimmed sway, and John’s effusive handling of the chorus is engaging in spite of itself, but the result is a mere bauble.

The misery and escalating drama packed into “Rotten Peaches,” on the other hand, is John’s wheelhouse, and he sells it with aplomb, ladling personality onto lyrics with persistent vocal accents that make his readings sound soulful—or at least personal. Flavorful and expansive, it contains the best hallmarks of his method.

Half a century later, it’s easy to forget a time before Elton John was embedded in popular culture and large pieces of his life were an open book. When Madman was released on November 5, 1971, John had not yet come out (first as bisexual, later as gay), so a key undercurrent of “All the Nasties” went undetected. Critics, particularly in England, had been rough on John, and he responded with a song that was a mixture of self-pity and defiance, wondering at its outset, “If it came to pass/That they should ask/What would I tell them.” At that point, no one knew. The song is defined by intensity; an amalgamation of a gospel invocation with an operatic choir swells toward the end, but never escapes melancholy.

In its wake, the stripped-down album closer “Goodbye” sounds lonely and lost. Likely unknown to John at the time, it also served as a wistful send-off to a method he had employed to that point in his career. With his next album, John would move toward band-driven recordings created outside of traditional studios, helping to narrow the gap between his studio and stage dynamics. Nevertheless, the language with which Madman was filled would rear its head frequently, with expanded vocabulary, in years to come. It would prove the first in a lengthy string of classic albums, a building block of a golden era in one of popular music’s great careers.

6 Comments

This is probably my second favorite EJ album, being nosed-out everso slightly by “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. Both these albums fall into that magical ’70-’77 time period that defines, more than any other time, John’s career. “Madman” was my first exposure to EJ, and came, not from the “Madman” album itself, but from one of those “hits of the day”, multi-artist, records put out by a company named K-Tel. This particular album featured, as one of the assembled hits, “Levon”. I think it was my brother’s record, that I, as a very curious 11 yr. old, “narrowed” when he was away one day.

Just as Lennon-McCartney had the production of George Martin, John-Taupin had Gus Dudgeon. In addition, the John and Taupin team had another very important ingredient in their mix. Paul Buckmaster. He was responsible for the string arrangements that were such a vital, almost signature part of mix. This was particularly important on John’s earlier albums that were made during that magical time period of 1970-1977. The four person team (John, Taupin, Dudgeon, and Buckmaster) were a very formidable presence in the music industry.

This probably does not make it into my Top 5 EJ best album list but I think it’s due for another listen based on your review. Tumbleweed Connection still stands as #1 for me and Madman never had as much depth to me. I remember it being about 2 songs plus the title track. Will have to revisit.

If “Levon” is a tough song to cover, the title track “Madman Across the Water” must be even more forbidding. Yet Brandi Carlile has done so, and amazingly aced it. Check it out here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVOstw9eKdE

To discuss the track “Madman Across The Water” without making mention of Chris Spedding’s lead guitar work is a truly glaring omission. The understated, yet immensely dark and powerful lead lines the English guitar legend provides throughout the song are one of the major ingredients that bring it to life.

Not only is it mentioned, there’s video for it. Look again.

And the title track is not mentioned ?