When Eric Burdon and the Animals took the stage at the Monterey International Pop Festival on the evening of June 16, 1967—following Johnny Rivers and preceding Simon and Garfunkel—they were a vastly different group than most in the audience remembered.

When Eric Burdon and the Animals took the stage at the Monterey International Pop Festival on the evening of June 16, 1967—following Johnny Rivers and preceding Simon and Garfunkel—they were a vastly different group than most in the audience remembered.

The Animals had come to American listeners via the British Invasion of 1964, climbing to #1 that summer with their intense, blues-informed rendition of “The House of the Rising Sun,” a song with roots at least a century old and a subject that didn’t often find its way to the top of the pop charts: the ruin of a “poor boy” via drinking, gambling and spending too much time around the “house” of the title, generally understood to be a brothel. Versions had been waxed previously by Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Nina Simone and even Andy Griffith (yes, that Andy Griffith) but the Newcastle quintet featuring singer Eric Burdon, keyboardist Alan Price, guitarist Hilton Valentine, bassist Chas Chandler and drummer John Steel was the first to put it into a rock framework, creating a smash hit in the process.

Over the next couple of years the Animals would continue to pump out rock classics—“Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” “It’s My Life,” “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and others—but by early 1966 they’d already fallen apart, with Burdon going to work on a solo album and Chandler discovering a wild American guitarist named Jimi Hendrix, whose management he would take on.

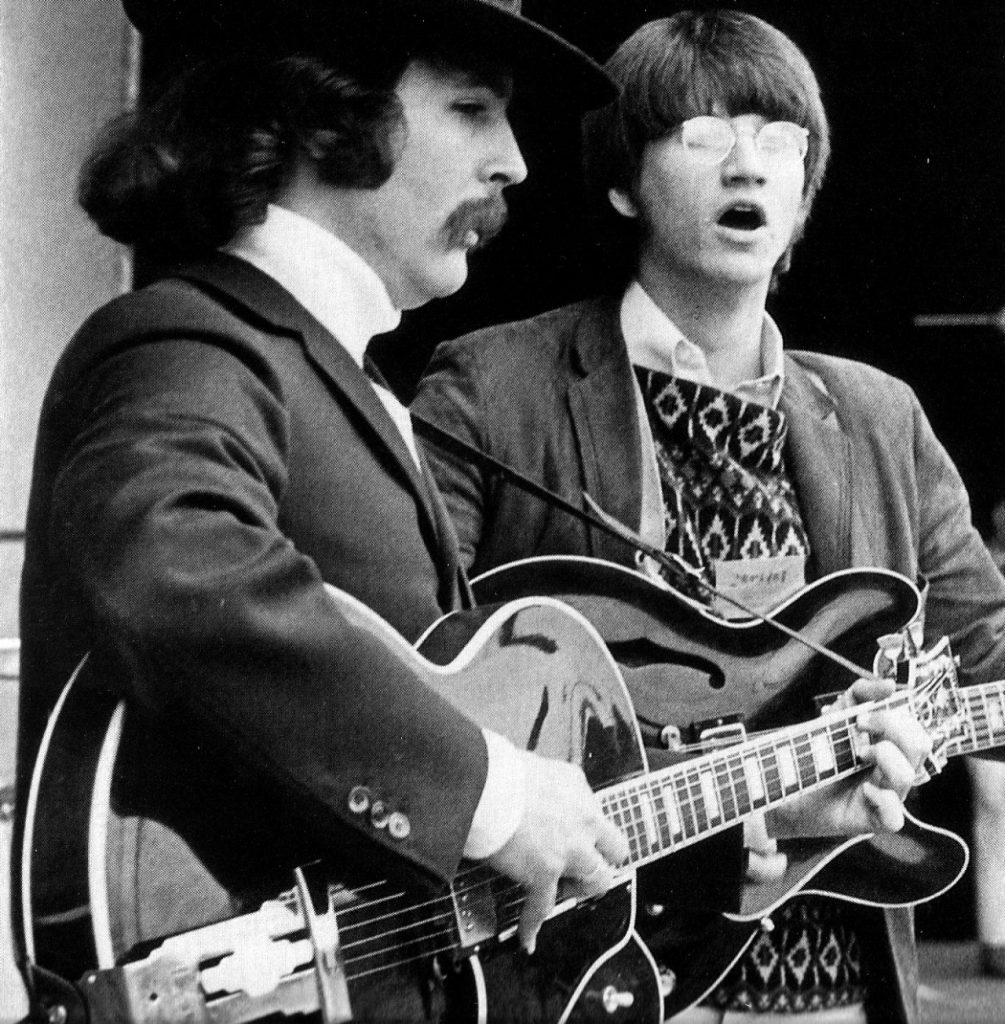

Burdon didn’t let the split impede his creativity though. By that fall he’d already put together a new band, this time taking the top billing: Eric Burdon and the Animals featured John Weider (guitar/violin/bass), Vic Briggs (guitar/piano), Danny McCulloch (bass), Barry Jenkins (drums) and, of course, Burdon up front as vocalist. By the fall they’d already notched their first top 10 single under the new rubric, “See See Rider,” with “Help Me Girl” and “When I Was Young” landing in the top 20 right behind it.

Although the blues was still at the core of the new Animals’ music, Burdon—like most of his British brethren in the Beatles, Stones, Yardbirds, Who, etc.—was moving in other directions, experimenting with broader musical ideas and lyrics that conformed more closely to the flower-power ethos of the era than anything Sonny Boy Williamson or Muddy Waters might have penned. Burdon, in fact, left England and settled in California, so it made sense for the group to grab a slot at the big festival being organized in the coastal town by entrepreneur Lou Adler, the Mamas and the Papas’ John Phillips and others.

At Monterey, the group’s four-song set surely surprised anyone expecting the same band that had arrived three years earlier. Eric Burdon and the Animals opened with “San Franciscan Nights,” a winsome new ballad that extolled the virtues of the unfolding Summer of Love scene up north, with lyrics like, “Strobe lights beam create dreams, walls move, minds do too, on a warm San Franciscan night.” That was followed by two songs, “Gin House Blues,” an old jazz/blues tune that had been recorded for the band’s Animalization album in 1966, and “Hey Gyp,” a cover of a Donovan song from their Animalism album later that year.

For their finale, the new lineup pulled out all the stops, transforming the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black” into a steamy, spooky, violin-powered lysergic hoedown, complete with liquid light show, stoned Burdon rap and chaotic crescendo that served its purpose of redefining Eric Burdon for the new aesthetic. At seven-and-a-half minutes, it was one of many highlights of the Monterey Pop documentary that followed the year after the festival.

Watch Eric Burdon and the Animals perform “Paint it Black” at Monterey

Related: 10 killer performances from Monterey ’67

The Monterey Pop Festival had a massive effect on Burdon. In the months after the experience, he and the group got together and crafted a song that pondered the larger significance of the event while also name-checking several of the artists that made it so special. Credited to all five musicians in the band, and produced by the great Tom Wilson (Dylan, Zappa, Simon and Garfunkel), “Monterey” was released in the U.S. on MGM Records in November 1967 and began its climb to #15 nationally.

A driving, blues-based rocker with a fierce, persistent bass line, it begins with a recap of what had happened at the Monterey County Fairgrounds that June, with lyrics telling of “young gods” smiling upon the crowd, flowers being given away, children dancing night and day and religion “being born.”

But where the song gets really interesting is in the second verse, as Burdon recalls several of the artists whose appearances at the show helped make it a cultural landmark we still celebrate half a century later:

“The Byrds and the Airplane did fly

Oh, Ravi Shankar’s music made me cry

The Who exploded into fire and light

Hugh Masekela’s music was black as night

The Grateful Dead blew everybody’s mind

Jimi Hendrix, baby, believe me,

set the world on fire, yeah”

As Burdon sings, the band does its best to approximate the sound of each artist being cited, a sitar-like electric guitar punctuating the Shankar mention (which, by the way, Burdon audibly mispronounces as “Shanknar”), a power chord blast and feedback for the Who, a snippet of snaky psychedelic guitar for the Dead, a blast of trumpet for Masekela, etc.

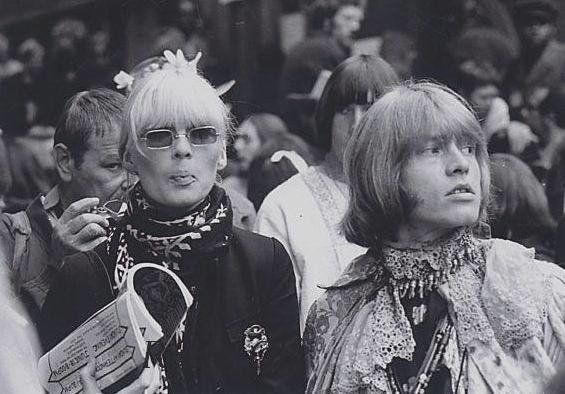

For verse three, there’s one last name-drop, “His Majesty, Prince Jones,” referring to Brian Jones of the Stones. The Rolling Stones did not play Monterey, but Jones, a virtual peacock in his regal finery, moved among the audience (and can be seen briefly in the D.A. Pennebaker documentary), just another hippie enjoying the music and the company and whatever else came his way. From there Burdon and the group reiterate the song’s main theme:

“Three days of understanding, of moving with one another

Even the cops grooved with us

Do you believe me, yeah

Down in Monterey, down in Monterey”

It ends with a recap and a message:

“Ten thousand electric guitars were groovin’ real loud, yeah

You want to find the truth in life?

Don’t pass music by

And you know I would not lie, no, I would not lie

Down in Monterey…”

Then, borrowing a line from the Byrds’ “Renaissance Fair,” Burdon muses, “I think that maybe I’m dreaming,” as “Monterey” winds down.

“Monterey,” like the Joni Mitchell composition “Woodstock” that would follow a couple of years later (and become a hit via Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young), didn’t tell the whole story. But it gave enough of a glimpse into a moment that came to define these artists’ era—and that of the generation that lived through it, whether they were fortunate enough to be at the events or just enjoyed them vicariously via records and films.

Related: Our interview with the five original members of the Animals

Bonus—Here is some interesting trivia about the artists named in the second verse:

The Byrds: Monterey proved to be the beginning of the end for David Crosby’s involvement in the L.A. band. Tensions between the guitarist/singer and other members were already heating up when Crosby used the festival as a soapbox to espouse upon his theories about the JFK assassination and the benefits of LSD, among other topics. In October, Byrds leader Roger McGuinn fired Crosby, who had also sat in with Buffalo Springfield at Monterey, in place of the absent Neil Young. He and that band’s Stephen Stills would find each other again in a year or so.

Jefferson Airplane: If you watch the Airplane’s segment of the film Monterey Pop, you hear the gorgeous ballad “Today” from their recently released album Surrealistic Pillow. You see Grace Slick’s mouth moving throughout but you hear only the band’s lead male vocalist, Marty Balin—he is never seen throughout the song. What happened? “It was a dumb problem,” filmmaker Pennebaker told this writer. “We didn’t know until we sent the film up [to be processed] that there was no microphone on her. And the only lighting was not on him, but on her. We thought we could get by on psychedelic.” What did Balin think of it? “I was really hurt,” he told me. “I was young and I was like, ‘Awww, I sing the song and I don’t even get to be seen.’”

Ravi Shankar—The Indian classical sitarist was revered by the young rock crowd for his association with George Harrison and for bringing an Indian music influence into rock overall. At Monterey, he was given an entire block of time to himself, on the afternoon of June 18. Shankar enjoyed the experience of playing to the young Americans. “Monterey was something which I liked because it was still new, fresh,” he told NPR. “In spite of the drugs and everything, when these young girls and boys, they showed these two fingers like that, like a V, and said peace and love and offered you a flower, there was some innocence. There was some beauty, which touched me so much.”

The Who: Although they’d received some airplay in America and had performed in New York and done a handful of other gigs in the States, Monterey broke them wide open in this country. Prior to the band’s appearance, the Who’s Pete Townshend was well aware that another relatively unknown act, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, also engaged in theatrical faux-violence onstage, and was worried about having to follow the American guitarist. It came down to a coin toss and the Who went on first, Townshend famously smashing his guitar to bits. Separating them from Hendrix was the Grateful Dead, whose Jerry Garcia was reportedly disgusted by both acts for destroying perfectly good instruments.

Hugh Masekela—The South African trumpeter was the only jazz artist booked to play the Monterey Pop Festival. (The site of the festival has also been used for the annual Monterey Jazz Festival since 1958.) Masekela was not unknown to the rock crowd: The Byrds, just a few months earlier, had featured his solo on their hit single “So You Want to Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star.” A year after Monterey Pop, Masekela would have a #1 single of his own in the U.S., “Grazing in the Grass.”

The Grateful Dead—Although still relatively unknown outside of San Francisco in June 1967, the reputation of the Grateful Dead was starting to spread quickly among the rock cognoscenti. The largely improvisational band was said to be—along with the Airplane and a few others—the personification of the new freedoms exhibited by the Bay Area’s rockers in the psychedelic ballrooms up north. The thing is, the Dead, and all of the San Francisco bands, were initially reluctant to play Monterey, distrusting the L.A.-based organizers and seeing the festival as a commercialization of the music. They refused to sign a release to have their performance included in the now-iconic documentary. True fame would continue to evade them for a few more years.

Jimi Hendrix—What can be said about Hendrix at Monterey that hasn’t been said already? The flamboyant freakishness, the burning of the guitar, that look on the audience’s faces as they try to comprehend what they are witnessing. What most folks don’t know is that the guitar that Hendrix torched at Monterey, squirting lighter fluid on it and then flicking a match, was not the guitar he used for most of his set. Just before his stunt, Hendrix swapped out one black Fender Stratocaster, his favorite at the time, for a similar model that had already been repaired. The burned-out guitar was sold at auction in 2012; the one it replaced is up for auction on June 17, one day short of the 50th anniversary of his Monterey career breakthrough.

Watch the video for Eric Burdon and the Animals’ “Monterey”

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

5 Comments

I guess Eric was not so impressed by Janis when he wrote the song Monterey.

Really enjoyed that article, Jeff. I didn’t think there was that much to still be leaned about the festival, but you revealed so many more interesting facts. I especially enjoyed the breakouts about each band/performer that played there. I had not heard about Hendrix’s guitar switch before. He ended up playing so many different guitars in the relatively short period of his performing career, that it never occurred to me that he actually had a favorite guitar.

geez, jeff… i thought i was good with lyrics, but i thought he said “prince george”, which always puzzed me.. dammit! ya got me AGAIN!

Eric Burdon & the Animals were a classic group. Too bad they didn’t make more albums together or even reunite down the road. They had some classic songs, “Year of the Guru,” “Sky Pilot,” A Girl Named Sandoz,” and “When I Was Young” are just a few classics. One of my favorite psychedelic bands of all time.

I thought Eric did a dead-on Jimi when he was yelling “Monterey!”