Country music’s influence on rock ’n’ roll is nearly as old as rock itself, a dominant gene in rockabilly and vocal touchstone for seminal artists from Elvis to Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers. But for country rock, 1968 was Year Zero—the rise of a school of artists consciously bridging those genres. It’s a testament to the vitality of that equation as well as its accelerating pace that two of the sub-genre’s defining albums would overlap in conception even as the bands creating them buckled under internal strain.

Country music’s influence on rock ’n’ roll is nearly as old as rock itself, a dominant gene in rockabilly and vocal touchstone for seminal artists from Elvis to Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers. But for country rock, 1968 was Year Zero—the rise of a school of artists consciously bridging those genres. It’s a testament to the vitality of that equation as well as its accelerating pace that two of the sub-genre’s defining albums would overlap in conception even as the bands creating them buckled under internal strain.

The Byrds had enjoyed first mover advantage in recording Sweetheart of the Rodeo, spurred on by Gram Parsons, a 21-year-old singer-songwriter whose deep love for Southern country and R&B found a kindred spirit in bassist Chris Hillman and pragmatic support from lead guitarist Roger McGuinn. Country influences were already in the air, not only in originals and covers from the Beatles, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Buffalo Springfield and the Byrds themselves, but also in up and coming artists like Bobbie Gentry and Linda Ronstadt.

Yet, even before Sweetheart hit stores in late August, Parsons had bolted from the band on the eve of South African dates and veered into a bromance with Keith Richards that injected the Rolling Stones with country influences while fanning Parsons’ own dreams of rock glory. After hanging out in London with Richards, Parsons returned to Los Angeles in early August weighing his next move.

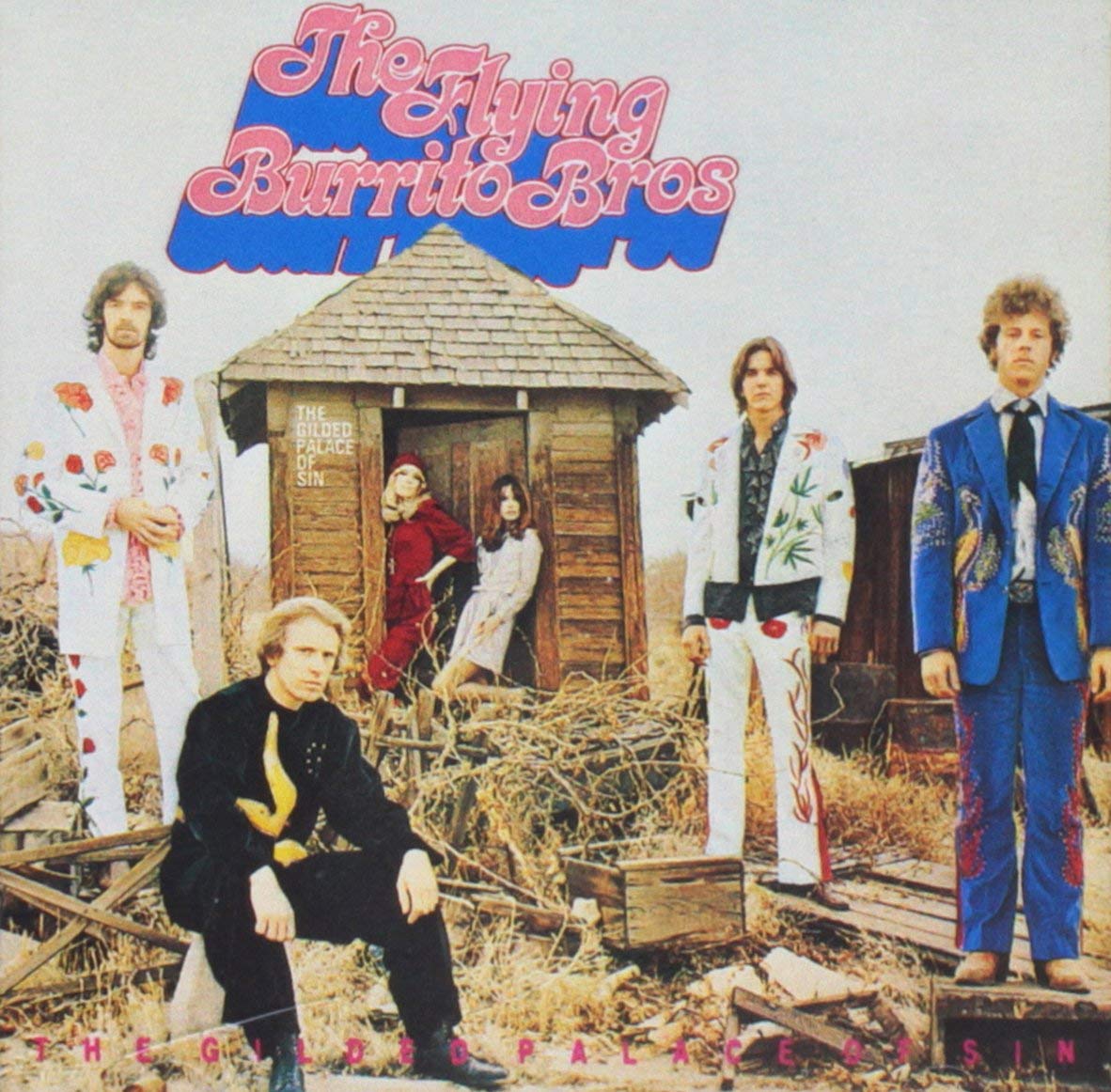

Meanwhile, Chris Hillman had flown the Byrds’ coop after increasing tensions with management. Despite an earlier falling out with Parsons, Hillman reconciled with the Florida-born, Georgia-raised musician. The erstwhile combatants once more bonded over music and even became roommates, writing the bulk of what would become the original material on the debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, for the Flying Burrito Brothers. Chris Ethridge was recruited as bassist, freeing Hillman to play guitar and mandolin, and the duo tapped Sneaky Pete Kleinow on pedal steel guitar.

The chance to snag a new band with two Byrds quickly drew competing bids from Warner Bros. and A&M Records, with A&M winning the battle. In contrast to the sessions for Sweetheart, shepherded by a seasoned producer and crack session players, the Burritos entered the studio with a big advance, a lot of ideas, a fledgling co-producer who was no match for the strong-willed Parsons and Hillman, and no drummer. The Burritos would share producer credits with A&M’s Larry Marks and engineer Henry Lewy, reflecting a more chaotic studio environment that would find them going through drummers nearly as rapidly as Spinal Tap.

Listen to “Christine’s Tune”

Gram Parsons had envisioned the Flying Burrito Brothers as “his” band, but The Gilded Palace of Sin, released in early February of ’69, underscores the partnership between Parsons and Hillman, who co-wrote six of the album’s eight originals. The opening track, “Christine’s Tune,” finds them sharing lead vocals and driving acoustic rhythm guitars, with harmonies built on classic thirds that harken back to the Louvin Brothers, the Everlys and other high, lonesome harmony singers. An overly ripe bassline evidently designed to emphasize rock power loses its edge to muddiness, but Sneaky Pete’s pedal steel commands center stage with an aggressive, fuzz-toned attack and his own unorthodox tunings.

Related: Our Album Rewind of the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo

A stop-motion animator and special effects craftsman, Kleinow provides a potent departure from the more traditional steel parts heard on Sweetheart, leaning here into the rock side of the sub-genre’s equation. Kleinow unleashes that power elsewhere on Gilded Palace while proving his skill with more traditional accents on the ballads, starting with “Sin City,” a country waltz that trades in the sin and salvation polarity central to Parsons’ vision for an amalgam of country, rhythm ’n’ blues and rock.

Its synthesis of country soundscape with urban modernism strikes an apocalyptic tone. “On the thirty-first floor, a gold-plated door won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain,” the duo sings in a prophesy that warns “this old earthquake’s gonna leave me in the poor house.” They could be singing about L.A. or Las Vegas; heard today, it’s hard not to envision the gilded escalators in Trump Tower.

The R&B component in Parsons’ “cosmic” Southern synthesis leads him back to Memphis, source for Sweetheart’s countrified R&B cover (“You Don’t Miss Your Water”). this time yielding two superb ballads sharing lyrics from Dan Penn. “Do Right Woman,” written with Chips Moman, was a sensuous Aretha Franklin cut demanding equal sexual satisfaction from her man, a contract that survives its gender flip as another gliding country waltz.

Instead of changing the mood or their compass bearings, the Burritos follow with the darker sexual torment of “Dark End of the Street,” a Penn collaboration with Spooner Oldham. Parsons dominates the vocals with an audible anguish over a locked battle between passion and guilt for two lovers “hiding in shadows where we don’t belong,” resigned to the inevitability of discovery and shame in a tableau of illicit love familiar in both country and soul tropes.

For two self-referential album tracks, Parsons wrote with Chris Ethridge. “Hot Burrito #1” is another soulful ballad that dispenses with any hint of sexual guilt to remind an ex-lover that “I’m the one who showed you how/To do the things you’re doing now” in frank sexual metaphors. With “Hot Burrito #2,” Ethridge grounds the track in a strutting bassline as Parsons rants about a lover’s quarrel with an eyebrow-raising opening “Yes, you loved me and you sold all my clothes.” If the lyrics verge on incoherence, the track itself is a lively standout.

Elsewhere, Parsons and Hillman nod to the tension between their music’s Southern roots and their countercultural instincts. On “My Uncle,” Hillman takes the lead on vocals and mandolin as a young American pondering the draft who’s “heading for the nearest northern border” against a fleet bluegrass backdrop. And on the closing “Hippie Boy,” Hillman reverses roles for a poker-faced, spoken word sermon as a redneck whose encounter with a hippie brings something like peace, love, understanding and the sage advice to “never carry more than you can eat.”

With the album completed, the Burritos recruited a third Byrd, drummer Michael Clarke, but chaotic behavior sabotaged supporting tour dates as they burned through the label’s advance, missing a crucial New York date. The Gilded Palace of Sin stalled at #164 on the Billboard 200 chart, considerably worse than Sweetheart’s disappointing tally months earlier. The addition of Bernie Leadon would strengthen them musically, but Gram Parsons was already restless. He would leave “his” band after the Burritos completed a scattershot follow-up, Burrito Deluxe. The band’s recordings are available to purchase here.

Bonus video: Watch the Burritos perform “Hot Burrito #1” live on TV

Parsons died on September 19, 1973. He was just 26 years old.

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024