No other group in rock and roll history has done whimsy, wonder and understanding like the Kinks. They are sagacious masters of the personalized miniature, providers of maximum insights on the back of knowing where to look and how to see.

No other group in rock and roll history has done whimsy, wonder and understanding like the Kinks. They are sagacious masters of the personalized miniature, providers of maximum insights on the back of knowing where to look and how to see.

Their best recordings have a knack for being both esoteric—as if they couldn’t have been produced by anyone else—and of feeling familiar, like one has come home again after the long trip away. They suggest the comfortable fug of the room with the fireplace on the cold night, the storm raging outside, while fostering awareness—and appreciation—of the individualized room within one’s own breast.

Nor do any musical artists better epitomize British eccentricity, as extolled by George Orwell in his essay “The English People,” than these would-be hillbillies of Muswell, abettors and upholders of personal identity. They are strange, but also no more so than any of us when we set aside affectation, pretense and what we presume is expectation, and are most ourselves.

If anyone could mount a village green preservation society capable of withstanding the homogenized devolution and disintegration of the world outside the window, it was going to be the Kinks. They have been both rock and roll’s first protectors of the sacred realm of the individual, and the band that one feels would emerge from amidst the fallen rubble and rising dust as proof of having succeeded in the vital job.

The people who love The Kinks love them much. One is unlikely to be “kind of” into them. With that love comes gratitude. The Kinks didn’t just make music in their 1960s prime that could stand alongside the finest offerings from contemporaries like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, the Who and Bob Dylan. Their timeless—and outside-of-time—work resonates as if it has interceded on our behalf against needless forces bent on inducing maximum chaos, so that we may be upheld in pursuit of greater purpose and at least a few of us will make the most of the opportunity.

One experiences their triptych of late 1960s masterpieces—Something Else, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, and Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire)—and has the sense of stakes. If the Kinks didn’t stand for what the Kinks stand for, we’d all be in trouble.

Within the enclave—the mew, the cul-de-sac, the shady lane, the family dynamic, the sibling relationship—there are worlds, just as there is nowhere else that we come to better understand the ways of the world at large and its people, from every here to every there, than those realms within realms. Master the corner, and you may come to know the room.

The art of the Kinks is this idea put into musical practice, and it’s why their depictions of that which should no more be termed small than an ocean described as dry conveys greater meaning than anyone else’s big, bigger, biggest. Ray Davies knew the value of being and perceiving this way. Which is also why the Kinks have the value that they do.

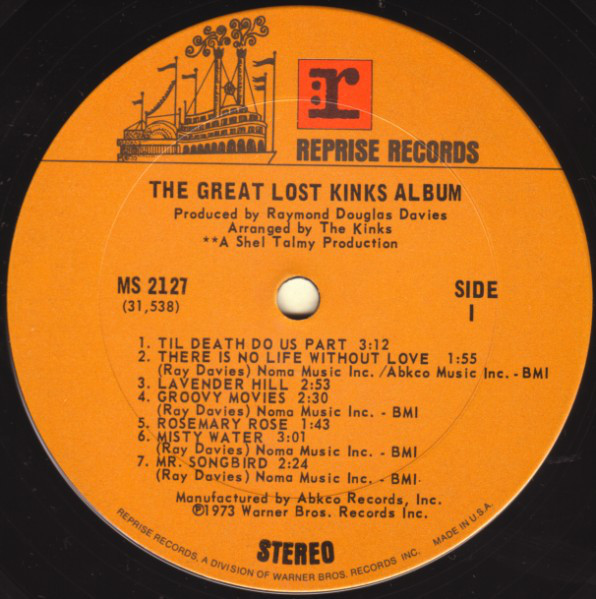

The subject of a different form of value was a sticky one for the Kinks and their former label, Reprise, in the early 1970s. The Kinks had been with Reprise for seven years when Davies elected to have the band sign with RCA, being disappointed with their Reprise contract.

During that same year, Reprise passed on issuing the Kinks’ Percy, the soundtrack to the film of the same name, concluding it was no fit for the American market. Even a Kinks masterpiece of masterpieces like “Waterloo Sunset” simply worked better in Essex than Idaho, for theirs was an indelibly British art, as much so as Wodehouse or Elgar.

Things are different when we’re talking the riff-ragers like “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night,” or even the boozy laconism of “Sunny Afternoon,” but it was no dice on Percy as far as Reprise was concerned, meaning the Kinks owed their old label a final record.

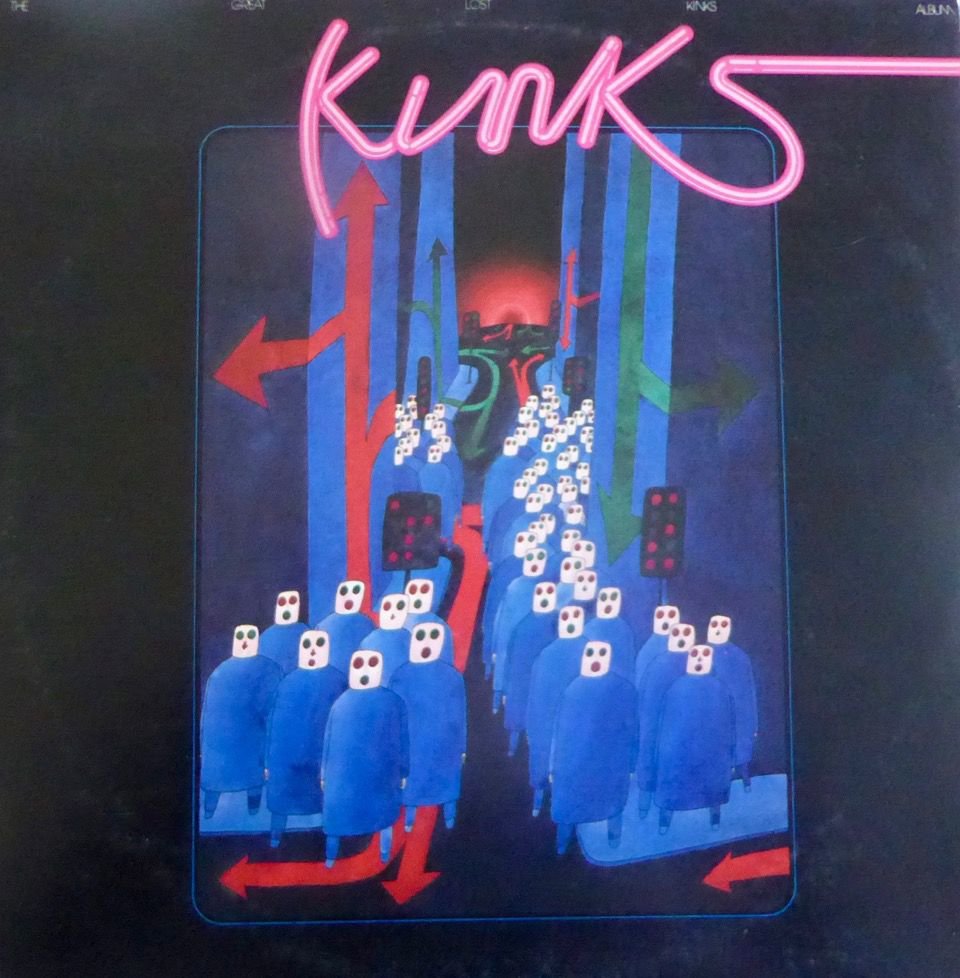

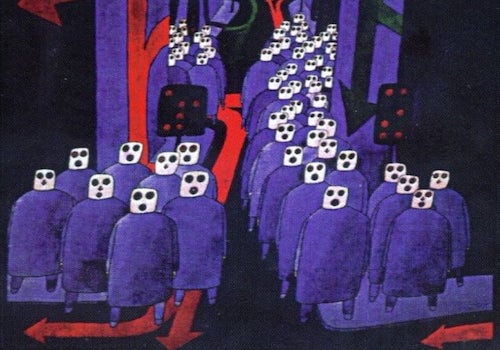

Which takes us to what became the loftily—though cheekily—titled, The Great Lost Kinks Album, one of those tucked-away joys of rock and roll that few people know about, due to being long out of print, and a lot more ought to.

Which takes us to what became the loftily—though cheekily—titled, The Great Lost Kinks Album, one of those tucked-away joys of rock and roll that few people know about, due to being long out of print, and a lot more ought to.

Were one to say that a sizable portion of the material on The Great Lost Kinks Album comes from the sessions for The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, then anyone familiar with that record would doubtless be primed for delight. Such a collection is going to have to be something special.

Few rock composers have had a three-album run like Ray Davies did across the aforesaid late-1960s trinity. He had mastered incisive whimsy: pointed—and sometimes finger-pointing—songs with altruistic warmth, and it’s what made him unique.

Reprise released The Great Lost Kinks Album in 1973. It featured 14 mostly unreleased cuts spanning 1966-1970. Numbering among the released material was the 1966 B-side, “I’m Not Like Everybody Else,” cantering with punk swagger but with a fundamental, balancing Socratic centeredness; an assertion of the undiminishable specificity of the self—and Orwell’s quintessential Englishman—that could only come from the likes of Davies in rock and roll.

The Animals had an earlier variant with “It’s My Life,” but whereas the Animals excelled at assertion, Davies’ songs were devotional acts of cognizance, with the outward distribution of that knowledge in following. John Fogerty may have played in a traveling band, but Ray Davies wrote songs of utility for a band that seemed to want to help you, whether that was to see, to be or both.

Davies’ thematic staple during these years was that through understanding comes growth, and the idea couldn’t fail to manifest itself in his songs of this period. Knowing or sensing this, a listener wanted more, wherever more came from.

Back in the here and now of 1973, as the Kinks became increasingly theatrical and devoted to artifice—not a Davies songwriting strength—the deep-canon nuggets of Great Lost must have seemed in need of a village green preservation society themselves. One pined for days that were no more; but at least the music proved eternal.

Brother Dave Davies co-wrote “There Is No Life Without Love” and was the sole author of “This Man He Weeps Tonight.” His was always a strange compositional case. He wrote strikingly; Something Else has a different timbre without his “Death of a Clown.” But it’s not as if anyone would wish for less Ray Davies material. So: something had to give, and that meant the inclusion of stirring songs from brother Dave.

As we see on Great Lost, Dave had a version of his brother’s gift for observation and nuance, and for couching what amounted to human-centric takeaways in instantly memorable melodies. For most guitarists, riffs are wholly rhythmic things, but Dave Davies—and “This Man He Weeps Tonight” is a perfect example—treated them as exercises in melody. They were less about the power of the thing than the lilt of it.

Even one of those proto-punk blasts like “I Need You” had a certain melodic through-line that one could imagine being more lightly transposed to, say, harpsichord. That number isn’t included here, but Dave Davies’ guitar dapplings and colorations are always in evidence. Ray was the writer in the Kinks, but Dave did the painting.

Packages of displaced or unreleased songs were the norm in the first half of the 1970s. The Rolling Stones issued the checkered Metamorphosis, while the Who brought out the more successful Odds and Sods.

Bands and their labels—more so the latter than the former—were punching back against the bootleggers who were themselves performing a significant service for people who took rock and roll seriously, though no one but those same people held that viewpoint, and certainly not any corporate suits losing out on potential sales.

What makes The Great Lost Kinks Album different than these other round-ups of scattered songs is how it holds together. Not only is it a viable album, it’s a viable late 1960s Kinks album, which is akin to saying something is a viable early 1970s Led Zeppelin album or a viable mid-1960s Beach Boys album.

Ray Davies’ opening “Til Death Do Us Part” is a song that’s completely at home with itself. It’s in no hurry, puts on no airs and lets its melody and the admissions of its protagonist do the talking. There’s a music hall aspect—though not in the preening style Davies came to obsess over in the 1970s—but it’s in a droll vein; less on the nose and more in the area of the cheek.

People don’t talk about Davies as a superior singer, which is fine, but we’d be amiss to make light of just how thoroughly he sings life into his characters, and how thoroughly he allows them to sing their lives through him.

As album openers go, you’d be challenged to find one more ingratiating than “Til Death Do Us Part,” and we’re talking a band that excelled with providing irresistible openers, as “David Watts,” “The Village Green Preservation Society” and “Victoria” attest.

The Kinks had a hard and a soft side, even as Ray Davies was consistent as a writer of narratives in song form. Or, if not narratives, vignettes of what it means to be human, in assorted forms.

The hard side came to an end with 1966’s Face to Face. After that, Dave Davies’ guitar mellowed (though he still returned to the jagged edge when necessary), his lines turning to a warm, slightly burnt bronze in the autumn sun for the rest of the glory phase.

There’s no guitar solo, of course, on “Waterloo Sunset,” but what Dave Davies creates tonally through his instrument makes for some of the most inspiring playing—inspiring in how one then goes out and decides to see the world with greater depth and clarity than before. Things just look differently after you hear the softer-sounding version of the Kinks.

Ray Davies’ songs slot into this category on The Great Lost Kinks Album. “Mr. Songbird” has a bonhomous skiffle feel. It’s a campfire singalong, but one for the early morning, when the birds are out and possibility abounds.

Davies’ subjects were often people in leafy environments; nature is present, only not at the fore, which makes “Mr. Songbird” different. The lens of observation is instead trained on the simple bird who is perhaps not so simple, and has his daily tasks—and daily music-making activities—to take care of as we do, r the song’s author does.

Davies himself didn’t think much of The Great Lost Kinks Album, regarding it as a contractual afterthought at worst, and an accidental record with a few redeeming touches at best.

One might liken it, though, to the Kinks’ version of the Beach Boys’ Wild Honey. We hear time and again about the heavy-lifters, the “official” all-time albums—a Something Else, a Pet Sounds—but there are many days when The Great Lost Kinks Album can hit its own special sweet spot. Unforced pleasure, incidental delight. It’s less a change of pace than a face one is glad to see again, even if it’s just been a day or two.

You’re never not pleased when you meet up with this album again. You hang out with it, it hangs out with you, and you sing along or whistle. The record gets in your head and stays there, an unobtrusive presence that shades the world at large a little bit differently. It’s a corner of the room worth spending some time in, window ajar, sounds from the lane coming to join you.

Watch Ray Davies sing “I’m Not Like Everybody Else” on Austin City Limits in 2006

Related: A look at two other ’70s Kinks masterpieces

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

9 Comments

Hi Colin,

I’m thankful for reading your article.

You nicely pointed out what sets the Davies brothers apart.

I’m into theatre and music, so for me their work is multiinspirational (next song to be recorded with honourable mention).

Greetings from Split, Croatia!

Alen Čelić

http://www.newgondoliers.eu

Thanks for this great review and for the context and references with other releases of that time. Mr. Fleming is obviously a big fan. Had never heard of this one, but more Kinks is always a good thing.

Hello. Just wanted to say that you very eloquently described the Kinks in a way that only a true Fan could appreciate. I very rarely leave compliments so your article was special. Thank you.

From one who was there , this album was hardly a cuddlefest between Ray Davies and Reprise Records , lovingly “curating” Rays sadly negleected unheard material . It was more or less a bootleg of songs whos publishing was in limbo ( a few of the songs dont even have publishing info on the cover or record ) . It , like Kinks Kronikles , was released as punishment for leaving the label . Great Lost was released straight to the 99 cent bins . 50 years later i have still never seen a standard issue without a hole or a cut . To be clear , Reprise illegally and completely unauthorized released half finished unpublished tracks and the record was under injunction upon release . I wouldnt ask Ray Davies about this one if i were you . By the way – i love the record . it would have been a solid disc 2 had there been a proper super deluxe of the Lola / Percy era .

Neither Dave nor Ray will ever die. Neither will give the other satisfaction for outliving the other.

I actually bought this on the strength of the Kinks name (no nocks or cuts!), not realizing at age 14 that this was Reprise’s stab-in-the-back release of Kinks material after they’d nixed the Percy album. No wonder Dave and Ray wanted to end that horrible business relationship. Yet, an album of Kinks’ rejects and toss-offs holds its own against anyone else’s lead albums of the time.

Miss you guys and would love to see just one more appearance together, but I’m not holding my breath ~

Someone who understands!

The Kinks are the ultimate in “acquired taste” as far as classic rock ‘n’ roll is concerned. They stubbornly went their own way, eschewing all the latest fads and trends. They were so out of time and out of kilter in the psychedelic late 60’s. They were grounded, real, ‘normal’ in a world gone mad, and not embarrassed at all by it.

Now, their late 60s stuff (apart from the SOUND QUALITY compared to the Beatles) holds up better than just about anything from that time. I think that is the main reason that some much of their stuff is being “discovered” by a new generation of music lovers, 57 years removed from the start of the “golden age.”

After decades of searching, I finally found an affordable copy of this gem–one without a cut-out clip?! This is a great review of a lost classic.

I bought this album in 1973 and instantly loved it – the kinks have 700 songs in their catalog and hundreds of them are just as good as their hits – another cd that gets NO attention is the bootleg from 1980 – 10 or so songs for a play in San Diego called 80 days which is incredible – ray sang all the songs to show the actors how he wanted them to sing each song…so that includes the women parts – to this day I love pictures in the sand and living room light.

Neither Dave nor Ray will ever die. Neither will give the other satisfaction for outliving the other.

Miss you guys and would love to see just one more appearance together, but I’m not holding my breath ~