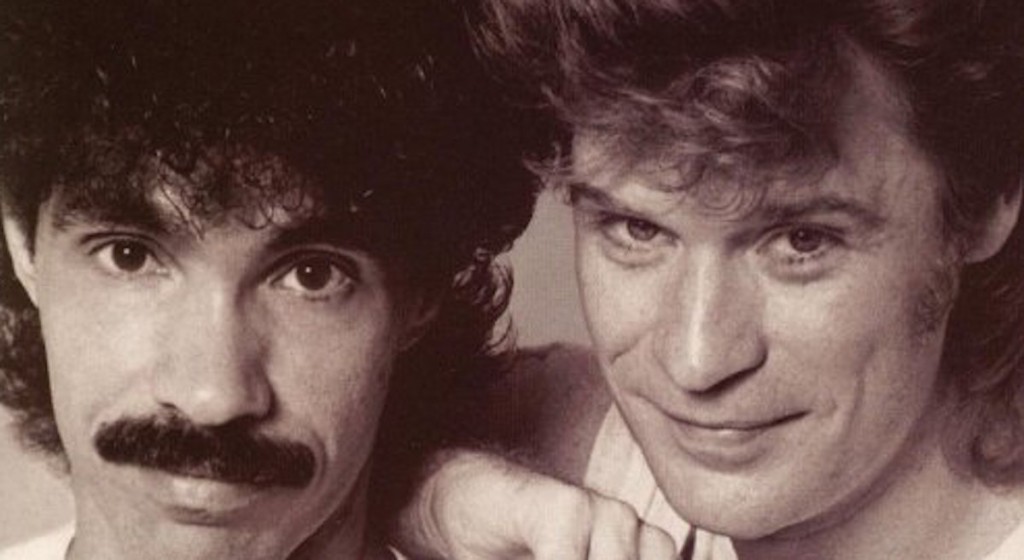

After their debut album Whole Oats failed to get much notice in 1972, the duo of Daryl Hall and John Oates moved to New York City from Philadelphia, where they’d struggled since 1968 to get traction for their music careers during and after studies at Temple University. In NYC, they could continue to work with the esteemed Atlantic Records in-house producer/arranger Arif Mardin. In addition, their old friend Christopher Bond played guitar, synthesizer and mellotron on the new sessions at Advantage Sound Studios and Atlantic’s own recording facilities, and contributed a lot of ideas, earning a credit as “production assistant” on the album eventually called Abandoned Luncheonette.

After their debut album Whole Oats failed to get much notice in 1972, the duo of Daryl Hall and John Oates moved to New York City from Philadelphia, where they’d struggled since 1968 to get traction for their music careers during and after studies at Temple University. In NYC, they could continue to work with the esteemed Atlantic Records in-house producer/arranger Arif Mardin. In addition, their old friend Christopher Bond played guitar, synthesizer and mellotron on the new sessions at Advantage Sound Studios and Atlantic’s own recording facilities, and contributed a lot of ideas, earning a credit as “production assistant” on the album eventually called Abandoned Luncheonette.

“We figured Christopher would be the right person to bring it all together,” Hall told Melody Maker in 1976, “because he knew us and knew what we were trying to do. We just tried to consolidate what we thought were our strong points and establish a sound that people could recognize. Up until that point we had a very schizoid identity.” Moving cautiously away from the folk base of Whole Oats, Hall & Oates concentrated on emphasizing their solid soul/R&B chops on their sophomore album. They had worked separately with the Philly producers/songwriters Thom Bell, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, and backed up visiting Motown acts at the Uptown Theatre and Adelphi Ballroom, working with their bands the Temptones (Hall) and the Masters (Oates). Before committing to develop an act with Oates, Hall was also part of Gulliver, a group with Tim Moore that released an Elektra album in 1970.

Mardin could see in Hall & Oates what he’d nurtured in the Young Rascals, a “white soul” aesthetic that could incorporate classical and even progressive-rock touches. “I didn’t feel the music was a powerful enough live vehicle to express how I felt when I was on stage,” Hall remembers about the Whole Oats period. “So we subtly started changing to fit that image of ourselves…I was always the kind of person to talk to myself. That’s basically how I work out my problems. That’s what I do in my music, I talk to myself.”

For the most part, aside from handling all the lead vocals, Hall plays keyboards and Oates guitars on Abandoned Luncheonette. Mardin brought in a raft of superb session musicians, including drummer Bernard Purdie, saxophonist Joe Farrell and bassist Steve Gelfand, to build tracks.

“When The Morning Comes” leads off the LP, with Hall singing his own composition in an impressive blend of tenor and falsetto voices. There’s a complex backing vocal arrangement, and the interplay of Hall’s mandolin and Oates’ acoustic guitar shows their folk stylings are still within reach. Percussion from Ralph McDonald, Farrell’s oboe and Bond’s mellotron are all carefully laid in as the melancholy lyrics reel out a sad story: “I went downtown to see my lady/She stood me up and I stood there waiting/It’ll be all right/When the morning comes.”

Oates takes lead on his own “Had I Known You Better Then,” and again his slightly rougher voice is arranged to weave in and out of Hall’s in support. The folksiness of acoustic guitars is still prominent. At the 2:30 mark Hall & Oates begin to interact in the soulful, loosely improvisatory manner that characterizes their newly emerging style, like two playful Marvin Gayes. Mardin’s subtle string arrangement, Gelfand’s chunky bass and Rick Marotta’s drumming stand out.

As solid as the openers are, “Las Vegas Turnaround (The Stewardess Song)” is the first truly outstanding cut on the LP. Written by Oates, it’s presented as a dual lead vocal, and the singing throughout is infused with joy. Musically, it at first sounds like a homage to Tommy James and the Shondells’ “Crystal Blue Persuasion,” with congas from Pancho Morales and light guitar chords. but it asserts its own quirky self quickly. By the time Farrell’s sax enters, we’ve got a Steely Dan-worthy blend of melodic, lyrical and instrumental elements going. The bridge section, with Oates almost scatting before an excited Hall enters, is especially impressive. Pat Rebillot’s organ part and Gordon Edwards’ bass are also praiseworthy. (And, yes, the Sara reference is to Hall’s girlfriend, later namechecked in the smash “Sara Smile.”)

The now-classic “She’s Gone” is next. The intriguing atmosphere is set before the first vocals enter at 50 seconds in, with Hall’s electric piano, Bond and Oates on keening electric guitars, Gelfand’s bass and the colors of Purdie and McDonald all doing their best. Hall & Oates, who co-wrote the tune, sing the opening lines “Everybody’s high on consolation/Everybody’s trying to tell me what is right for me” as a matched pair. This is where the reliable hit-making duo of the 1980s emerges from that “schizoid” world Hall hoped to transcend.

Mardin and Bond construct such a compelling musical backdrop you can hear Hall & Oates rise to the occasion with the intensity and focus of their singing. Farrell contributes a barn-burning sax solo; listen to the contrast with the smooth vocals as they re-enter, and that impetuous little string section swoop Mardin flies in. A full orchestra blossoms, guitars wail, and above all the singers dominate the last minute.

Related: Hall & Oates’ triumphant 2016 return to Madison Square Garden

As Oates told Sounds’ Ian Birch, the duo always sought to combine head and heart in their songcraft: “Like making a very, very personal statement but yet saying it in a way that a lot of people can relate it to themselves. That’s the secret of a good lyric. It’s that universal intimacy. I think that’s what we achieved with ‘She’s Gone.’”

Released as a single several months after Abandoned Luncheonette came out in November 1973, “She’s Gone” limped to #60 on Billboard’s Hot 100 pop chart. The R&B family band Tavares cut a version that made it to #1 on the Rhythm & Blues chart in late 1974; Hall & Oates had to wait for a re-release of their original in 1976 to finally get their just desserts, when it ascended to #7 on Billboard’s pop listing. By then, they’d already left Atlantic for RCA Records and scored big with “Sara Smile.” Radio stations were more than willing to give “She’s Gone” another chance.

The first side of the original LP concludes with the tender “I’m Just a Kid (Don’t Make Me Feel Like a Man),” written and sung by Oates. It’s an unusually structured song, with several sudden shifts in tone and tempo. Bond’s mellotron and Hall’s electric piano blend subtly with acoustic guitars from Oates and Jerry Ricks. In 2020, talking to American Songwriter, Hall called the album’s first side “magic,” and found no faults in it.

Hall was less complimentary about the second side of Abandoned Luncheonette, which he said relied too much on Bond’s obsession with the Beatles: “If I could change anything, I’d just get rid of all that crap and let the songs be the songs.” The LP’s title track, written and sung by Hall, kicks things off with another ambitious, multi-part song that moves through many changes, and definitely shows some influence from the Beatles and Beach Boys. There are harp glissandos, a gritty tenor sax solo, a bumping bass part from Edwards and background vocals that strongly involve Bond. The lyrics are surreal, with characters “sipping imaginary cola and drawing faces in the tabletop dust.”

The potent mandolin-acoustic guitar combo returns for “Lady Rain,” which also benefits from some haunting electric guitar supplied by Hugh McCracken and John Blair’s surprising electric violin, shrieking over a cello-heavy string arrangement. Hall & Oates wrote the song together and sing it with authority.

Thanks to Purdie and Gelfand, it’s also the funkiest track on the album. “Laughing Boy” is next. After a short mellotron intro, the writer Hall takes over, playing acoustic piano and putting down a passionate vocal that recalls his future collaborator Todd Rundgren. Marvin Stamm on flugelhorn contributes beautifully to a track that’s the least adorned on the set, but packs a punch.

The seven-minute “Everytime I Look at You” concludes the album, starting with more funk and several impressive guitar parts from Bond and Oates, which come to dominate the whole track. But Hall, his voice heavily processed, spends most of his time shouting in an unattractive, shrill way. Around five minutes in, Mardin and Bond reach for an epic, dramatic ending with a vocal chorus, before the track strangely yields to banjo and fiddle, as a hoedown commences until the final fade. Perhaps this is the most obvious track that Hall felt Bond blew up out of proportion, but his dismissal of the entire side two is surely off base.

Hall & Oates followed Abandoned Luncheonette with their last for Atlantic, War Babies, a radical shift toward hard rock and prog experimentation, produced by Rundgren and featuring members of his band Utopia. It bombed.

Abandoned Luncheonette took 29 years to achieve sales of a million copies, never getting higher than #33 on Billboard’s album chart even when “She’s Gone” was a hit the second time around. A hastily issued “best of the Atlantic years” titled No Goodbyes was issued in 1977 once RCA established the duo as one of their best-selling acts; it included the Abandoned Luncheonette rejects “It’s Uncanny,” “I Want To Know You For a Long Time” and “Love You Like a Brother.”

Hall & Oates were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014, with the admiring drummer/producer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson singing part of “She’s Gone” at the ceremony, saying, “Hall & Oates can cure any known ailment.” As one of history’s best-selling music duos, they’ve sold over 40 million albums and achieved six Billboard #1s out of their 33 charting singles, including “Rich Girl,” “Kiss on My List” and “Maneater.”

For over 50 years, Daryl Hall and John Oates have sustained solo careers and other collaborative projects as well as touring together, but in 2023 they were estranged, and some of their financial disputes went public. When Hall appeared on Bill Maher’s podcast he stressed Oates was his “business partner” rather than his “creative partner,” insisting, “We’ve always been very separate and that’s a really important thing for me.” But for millions of fans around the world, that ampersand in between their names is permanent.

Watch Hall & Oates perform “She’s Gone” live in 1976

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

1 Comment

It’s too bad that there’s “friction” between Hall & Oates. Part of that comes from Daryl committing the songwriter’s cardinal sin of selling his copyrights too cheap.