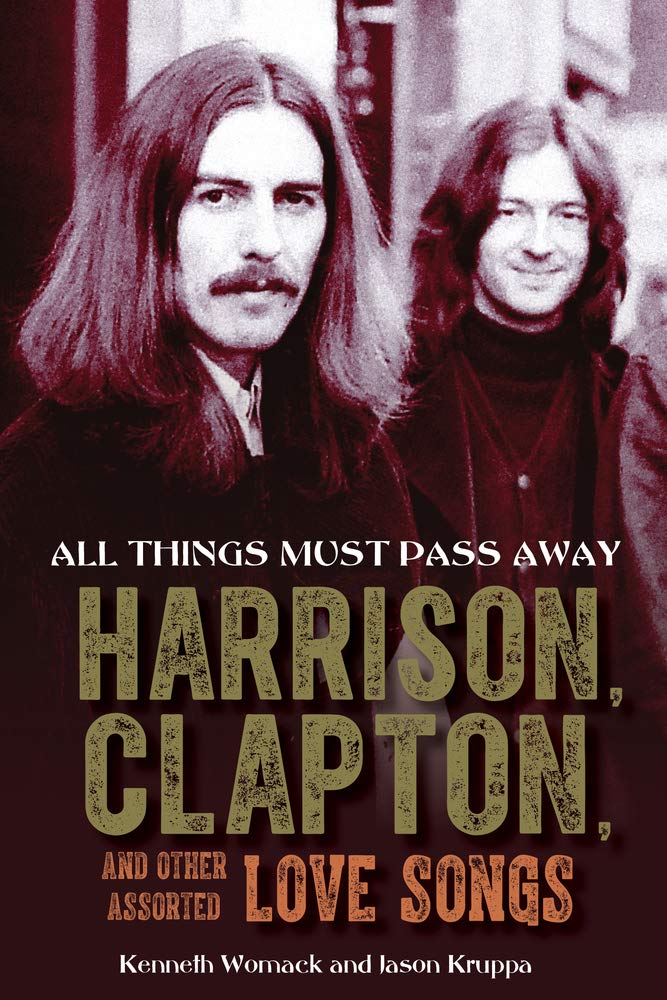

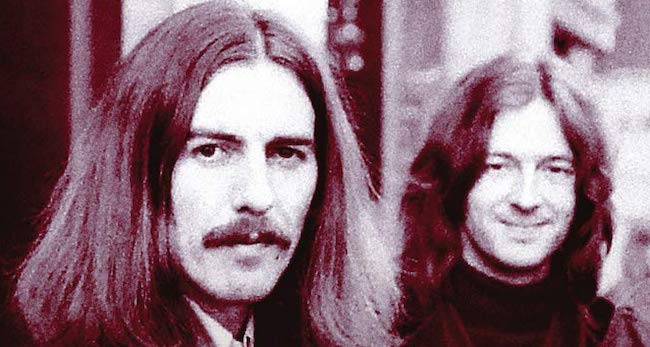

George Harrison and Eric Clapton are the subject of a 2021 book, All Things Must Pass Away: Harrison, Clapton, and Other Assorted Love Songs, about their legendary and tumultuous friendship that shaped not only their respective lives and careers but the shifting face of rock music itself in the early 1970s. The title, from renowned Beatles expert Ken Womack and music historian Jason Kruppa, arrived July 20 via Chicago Review Press.

George Harrison and Eric Clapton are the subject of a 2021 book, All Things Must Pass Away: Harrison, Clapton, and Other Assorted Love Songs, about their legendary and tumultuous friendship that shaped not only their respective lives and careers but the shifting face of rock music itself in the early 1970s. The title, from renowned Beatles expert Ken Womack and music historian Jason Kruppa, arrived July 20 via Chicago Review Press.

Best Classic Bands interviewed the authors and got some eye-opening revelations about the two star musicians’ chemistry, Derek and the Dominos’ participation on All Things Must Pass, and the continued “travesty” of a key missing credit.

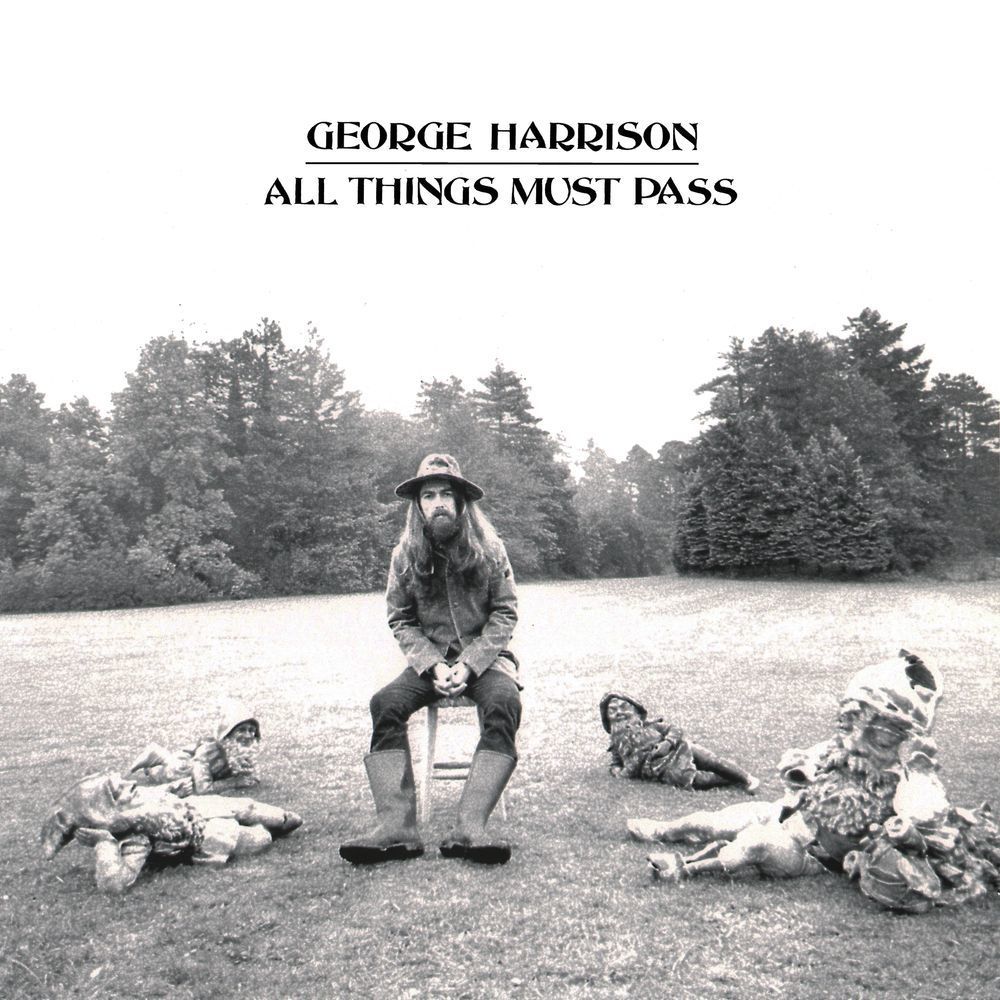

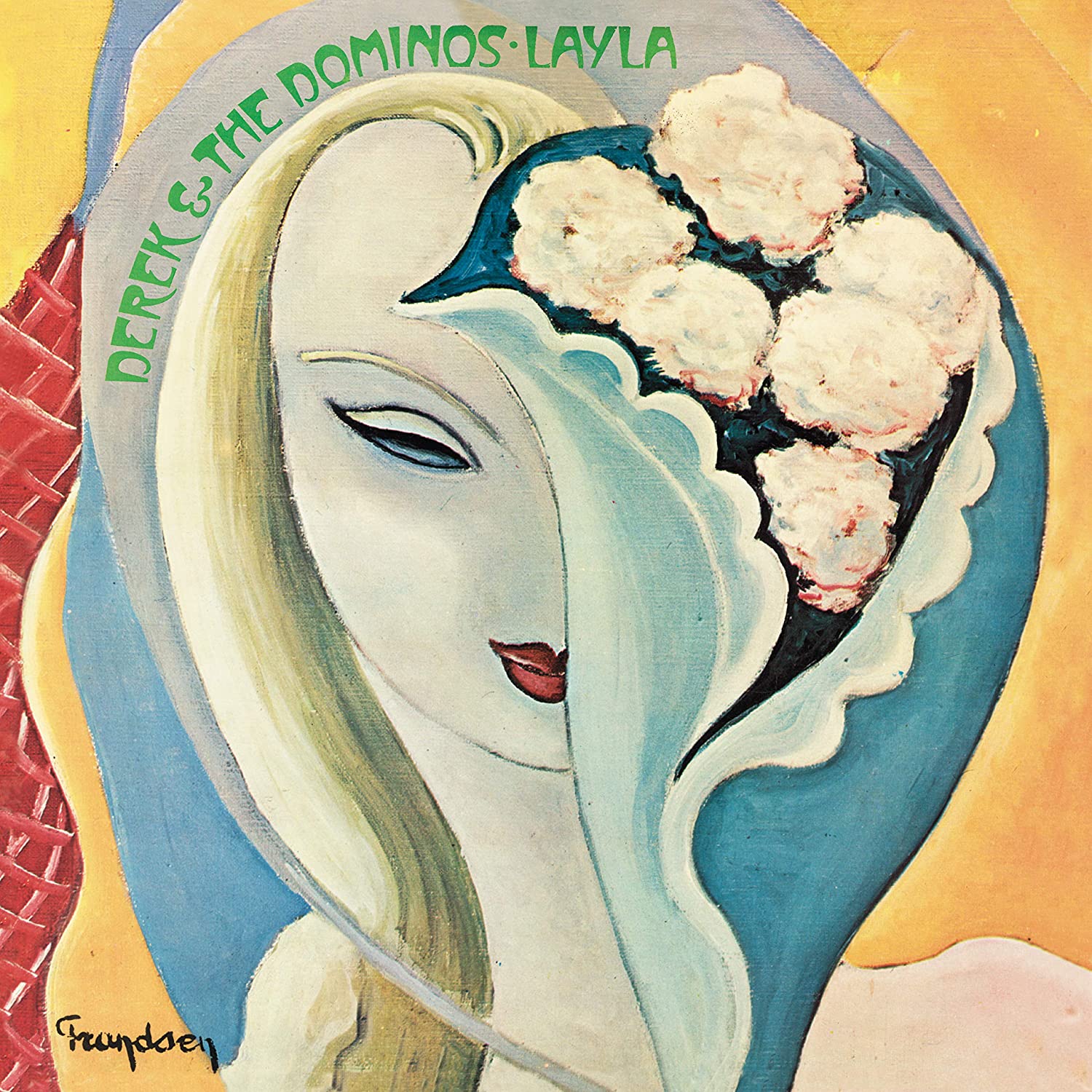

The book explores the legends’ musical and personal collaboration, friendship, and rivalry. Close attention is devoted to the climax of their shared musicianship—the November 1970 releases of Harrison’s emancipatory statement in the wake of the Beatles, All Things Must Pass, and Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, Clapton’s impassioned reimagining of his art via Derek and the Dominos.

Authors Womack and Kruppa examine these two iconic albums, and unearth new perspectives on Harrison and Clapton. Drawing on a mountain of archival material and featuring new research and new interviews with key participants, including drummer Alan White, bassist/Beatle confidant Klaus Voormann, Alan Parsons, and Chris Thomas, All Things Must Pass Away sweeps aside the myths in favor of a richly detailed exploration of these two remarkable albums and the men who made them.

How do you address George’s mindset with regard to the “rejection” of so much of his material by Lennon and McCartney?

Jason Kruppa: This is a complex subject. George admitted that his initial attempts at songwriting weren’t very successful, and the rejection of his songs early on forced him to work harder. As he practiced his craft, his world view was developing and he began to put more of his personal preoccupations into his writing. Beginning in late 1965, his songs improved dramatically, and John was certainly helpful and supportive around this time. However, George gradually became aware that some of his songs simply weren’t a good fit for the Beatles, and he mentioned in March 1970 that, “It was always a matter of trying to do the song you thought they’d understand quickest, or the song you could get onto the tape the quickest.” Listening to the Get Back tapes reveals that “All Things Must Pass” was one such song, where the Beatles rehearsed it repeatedly but it didn’t click with them, leading George to abandon it for the moment. He was also up against the Lennon-McCartney songwriting behemoth, which set the bar very high indeed and didn’t entirely allow for George’s perspective. Paul’s blunt comment at an Apple meeting in September 1969 that he didn’t think George’s songs had been good enough (prior to Abbey Road) put a fine point on his feelings about the matter, and John could be equally dismissive. Even with “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun” under his belt, George had internalized a Beatle Second Class mentality, and he consequently harbored certain insecurities about his songwriting as he headed into sessions for his own album. So he was on a hot streak from 1968-1970, writing all these songs, but then when it came time to record, he was at first unsure of which songs to do and would be surprised when the musicians responded sympathetically.

How did you sort through the personnel involved with ATMP? Were you able to uncover any new sources? Any major revelations that you can share with our readers? Is Lennon on any of it?

JK: After years of mostly just working with the three other Beatles in the studio, George essentially had an open door policy for musicians on his own album and would pull people in on short notice — Alan Parsons said he went to a couple of sessions and anytime a musician would show up, George would tell them to “find a guitar and join in.” Unfortunately, because no record was kept at each session of who played on what, it may be impossible to ever make a definitive personnel list, but by assembling a timeline of who was where, and cross-referencing interviews and a variety of other sources, we were able to determine a few things for certain. Maybe the most surprising discovery was that Derek and the Dominos, who were long assumed to have been the “house band” for the entire album, really only appear as a group for about a week and a half. (John Lennon was in Los Angeles undergoing Primal Therapy from April to September and so wasn’t in the country while George was working on the album.)

JK: After years of mostly just working with the three other Beatles in the studio, George essentially had an open door policy for musicians on his own album and would pull people in on short notice — Alan Parsons said he went to a couple of sessions and anytime a musician would show up, George would tell them to “find a guitar and join in.” Unfortunately, because no record was kept at each session of who played on what, it may be impossible to ever make a definitive personnel list, but by assembling a timeline of who was where, and cross-referencing interviews and a variety of other sources, we were able to determine a few things for certain. Maybe the most surprising discovery was that Derek and the Dominos, who were long assumed to have been the “house band” for the entire album, really only appear as a group for about a week and a half. (John Lennon was in Los Angeles undergoing Primal Therapy from April to September and so wasn’t in the country while George was working on the album.)

I’ve always enjoyed the album’s third disc, Apple Jam. Who doesn’t want to hear these great players improvising? Any tales you can share about these sessions?

JK: Those jams came out of Derek and the Dominos really tapping into the great energy they had found together. They jammed endlessly at Clapton’s home, and while they were very productive at George’s sessions, they couldn’t help but bring that energy with them. Ironically, on “Out of the Blue,” which has this really great dynamic give and take throughout, Klaus Voormann said he is the one playing guitar (“a little Gretsch guitar” that George had given him), and that Clapton isn’t even on the track!

Are there one or two musicians who sort of take over as musical director?

JK: George was fully in control of developing the arrangements in the studio, while Phil Spector would largely manage things from the control room, but this isn’t to say there wasn’t a lot of collaboration. Spector employed his Wall of Sound technique of doubling and tripling keyboard and guitar parts on some songs, while on others — particularly the more country-flavored tracks — George would decide the players needed to achieve the effect he wanted. Overall, though, George would allow arrangements to develop organically once he had taught everybody the song, but he was ultimately making the call on what he liked or disliked for each recording.

What do you think the sales/chart expectations were for the album when it was getting ready for release? Any thoughts on what was expected of “My Sweet Lord” as a single? (Record World called it a “double-sided smash” in its Nov. 28 review and I see that the song reached #1 in an unheard-of four weeks.)

JK: George was uncertain of the quality of the finished album, mainly because he was so close to it after working on it for so many months. Allan Steckler, Creative Director at Apple, told him it was “the most amazing album I’ve ever heard,” to which George responded with surprise and skepticism. He initially resisted releasing “My Sweet Lord,” ostensibly due to concerns that the single would take away from sales of the album, but he may also still have been worried that people would reject the song because of its spiritual message. Spector said he pushed him to release it as a single because he knew it was a hit. So while George seems to have been unsure, the people around him knew how good both the album and that song were.

Any thoughts on the album’s timing vis a vis the Plastic Ono Band album? Jealousies?

JK: After the album was finished, George recalled that John stopped by Friar Park (George’s estate in Henley) once when George wasn’t home, and when he saw the album cover said disparaging things about it to a mutual friend who was staying there: “He must be fucking mad, putting three records out. And look at the picture on the front. He looks like an asthmatic Leon Russell.” Even though George had been happily received when he popped into a session for Plastic Ono Band on October 9 to wish John a happy birthday, he characterized John’s comments by saying, “There was a lot of negativity going down.” John, of course, was often in a delicate emotional state, but there was also a senior Beatle/older brother dynamic at play here, so it may not have been jealousy as much as it was John in his very brutal way simply dismissing anything that didn’t suit his interests. This is similar to how Paul had said George’s songs weren’t good enough to merit equal space on a Beatles album until Abbey Road — through their lenses, these statements were irrefutable truths.

How do you address George and Eric’s calendar during the period that the book covers? Besides Clapton’s work on ATMP, any anecdotes that you can share of the two recording and performing together during this time?

Kenneth Womack: What is truly remarkable for both musicians is how incredibly busy they are during this period. Their stories offer a powerful narrative about drive and ambition, about realizing one’s talent and living in the moment. Eric’s work on ATMP is, in many ways, George’s secret weapon. Eric could always be counted on for a smooth guitar lead or slick rhythm backup. Their chemistry was apparent during the ATMP sessions, helped no doubt by their shared stint with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends.

By year’s end, ATMP was at #1 while Layla was pretty quiet. Much has been written about the somewhat tepid initial response to the latter. What do you point to for the reason(s)? Too soon after Clapton’s solo debut? Was the name of the band confusing?

KW: The confusion over the name Derek and the Dominos certainly didn’t help matters. Clapton’s handlers spent a great deal of time and energy trying to make his participation clear, including the famous “Derek Is Eric” buttons. Unlike ATMP, Layla didn’t have a clear hit-making single in its arsenal. This was a particular issue, given how competitive and crowded the rock charts were during this period.

KW: The confusion over the name Derek and the Dominos certainly didn’t help matters. Clapton’s handlers spent a great deal of time and energy trying to make his participation clear, including the famous “Derek Is Eric” buttons. Unlike ATMP, Layla didn’t have a clear hit-making single in its arsenal. This was a particular issue, given how competitive and crowded the rock charts were during this period.

Can you share a thought about Duane Allman’s involvement?

KW: Whereas Eric afforded George with a go-to musician during the early days of ATMP, Allman proved to be Clapton’s secret weapon in Miami, the missing element in terms of the Dominos’ sound. His guitar work, even 50 years later, is a wonder to behold.

How about Rita Coolidge’s possible contribution to the title track?

KW: Rita Coolidge’s omission as a songwriter on “Layla” is a travesty. Her melody formed the basis for the famous “Piano Exit,” which Jim Gordon purloined in the studio as the coda for “Layla.” This is an issue that Clapton could still correct on future releases of the song. It has been substantiated in several different quarters at this point. Outside of the arresting guitar riff for the title track, the piano melody has undoubtedly drawn thousands upon thousands of listeners to buy the album over the years. They’re both moments of high rock poignancy. Ironically, the introductory guitar riff in “Layla,” as with the “Piano Exit,” is also the result of theft—in this case, Duane lifted it from Albert King’s “As the Years Go Passing By.”

All Things Must Pass will receive an expanded, remastered edition for its belated 50th anniversary on Aug. 6, 2021. On Nov. 13, 2020, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs was reissued as a 4-LP vinyl box set and 2-CD edition for its 50th anniversary. The title, originally released on November 9, 1970, has been expanded to include bonus material not previously available on vinyl.

Womack is the author of the 2023 biography Living the Beatles Legend: The Untold Story of Mal Evans, Maximum Volume and Sound Pictures, the two-volume biography of George Martin, as well as Solid State: The Story of Abbey Road and the End of the Beatles and John Lennon, 1980: The Last Days in the Life. He is the host of the Everything Fab Four podcast. He delivers some 50 invited Beatles talks a year to audiences across the U.S.

Kruppa is a music historian and creator of the Producing the Beatles podcast.

Related: Listings for 100s of classic rock tours

- Waddy Wachtel on Touring With Stevie Nicks - 05/26/2024

- The ‘Lucky 13’ Number One Albums of 1968 - 05/25/2024

- Waddy Wachtel on Playing With Keith Richards, Linda, and More - 05/24/2024

5 Comments

I always heard that George’s early work was always rejected by Paul and John because they always sounded like other peoples songs. Ironically, even though “My Sweet Lord” was a hit, George was sued for plagiarism by the writers of “He’s So Fine”.

That was Ringo

Did Jesse Davis contribute as much as he seemed to on these recordings? He is present on videos of Concert for Bagladesh. He has always been one of my all time favorite underrated guitar players. Too bad he remains an overlooked side note. I think that he had no trouble standing with the best. Maybe not as a writer but certainly as a player.

No mention of Bobby Whitlock who was on nearly every song and there throughout the making of All Things must Pass,, don’t know why he is overlooked his organ, piano and voice all through the record. What a shame no mention.

The book is a terrific look into both guitarists and their recordings in 1970.

The story of Clapton as a boy finding a magazine on the street, and the aftermath, is a hoot. Not so much for young Eric. But you can imagine a teenage Austin Powers being influenced mightily.