When the British quartet Humble Pie picked their name, it was one way of humorously lowering the expectations of the U.K. music press and public, who, without hearing a note, had already anointed them a “supergroup” with a bright future ahead. In the 1960s, the raspy-voiced singer and songwriter Steve Marriott and guitarist-vocalist Peter Frampton had enjoyed considerable pop success as two of the “ace faces” of the Mod bands Small Faces and the Herd, and bassist Greg Ridley had been with the highly-respected progressive-rock group Spooky Tooth. Only the 17-year-old phenom on drums, Jerry Shirley, was relatively untested beyond his work with the Marriott-approved Apostolic Intervention, who had one single issued in 1967 before splitting.

When the British quartet Humble Pie picked their name, it was one way of humorously lowering the expectations of the U.K. music press and public, who, without hearing a note, had already anointed them a “supergroup” with a bright future ahead. In the 1960s, the raspy-voiced singer and songwriter Steve Marriott and guitarist-vocalist Peter Frampton had enjoyed considerable pop success as two of the “ace faces” of the Mod bands Small Faces and the Herd, and bassist Greg Ridley had been with the highly-respected progressive-rock group Spooky Tooth. Only the 17-year-old phenom on drums, Jerry Shirley, was relatively untested beyond his work with the Marriott-approved Apostolic Intervention, who had one single issued in 1967 before splitting.

After failing to convince his bandmates to let Frampton join Small Faces, Marriott formed Humble Pie with him in 1969. As Safe As Yesterday Is and Town And Country, two poor-selling LPs on Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate label that explored a number of musical styles, came out that year. But when Immediate went belly-up, Humble Pie dedicated themselves to a more focused hard-rock sound, signing to the American label A&M. Their eponymous debut in 1970 didn’t chart in the U.S., and the follow-up Rock On, produced at London’s Olympic Studios by Glyn Johns, was issued in March 1971 and peaked at #118 on Billboard’s album chart. This was a band with a lot of talent and not much to show for it.

Some American audiences did take notice of their developing “heavy” live act as Humble Pie played Detroit, Philadelphia, Grand Rapids, Buffalo, etc., in 1969-70, on bills with the Moody Blues, Mountain, Grand Funk Railroad and the James Gang. But when they opened for the Grateful Dead at the Fillmore West in San Francisco in December 1969, they were clearly out of their element. Critical response could be hostile. The Los Angeles Times’ John Mendelssohn, an admirer of Marriott’s voice and songwriting with Small Faces, panned Humble Pie’s 1969 debut at the Whisky A Go Go, writing, “The group seems very nearly obsessed with living down the talentless-teenybop image it wrongly suspects American audiences have of it…Toward this end it attempts to dazzle the listener with its instrumental proficiency, which it displays in doses of more than 20 minutes. It succeeds only in boring one senseless.”

As Rock On underperformed commercially, the band took drastic action under the guidance of new manager Dee Anthony and heavyweight booking agent Frank Barsalona; they moved to New York City, played as many shows as they could, and bet their careers on a live album, attempting to duplicate what Anthony had done for Joe Cocker when he recorded the Mad Dogs And Englishmen tour the previous year. It worked for Humble Pie too, when the double-LP Performance Rockin’ The Fillmore came out in November 1971 and became their first gold album.

Marriott told New Musical Express, “If we had stayed in England we would have broken up, because all it did was sap our confidence, and all America does is build up our confidence. We’ve realized that we’re a good band, not a flash in the pan supergroup.”

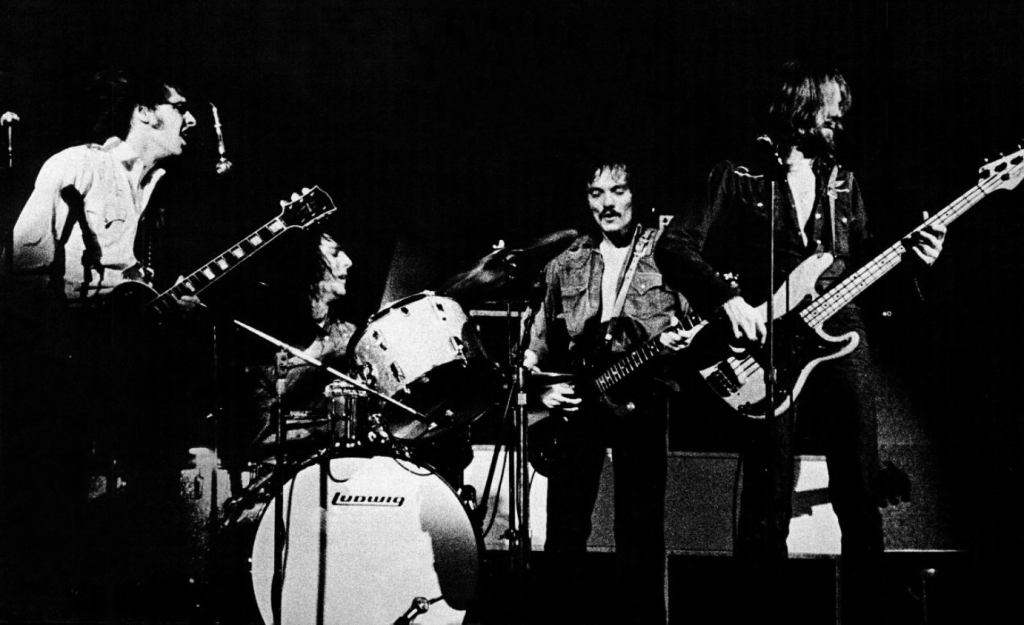

With the support of empresario Bill Graham, Humble Pie appeared at the Fillmore East on March 19-20 and April 5-6, then set up the FEDCO mobile studio, with engineers Eddie Kramer and Dave Palmer on hand, to record all four nearly identical shows on May 28 and 29, when they shared the bill with Fanny and Lee Michaels. (Graham later said he estimated 70 percent of the crowd had come to see Humble Pie, even though they weren’t headlining.) The Rock On standout “Stone Cold Fever” was only played once, at the early show on May 29, but it made the final cut for the new album, along with six other performances of blues songs by Dr. John, Ida Cox, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon and two associated with Ray Charles, “Hallelujah I Love Her So” and “I Don’t Need No Doctor.”

Related: A 1983 interview with Steve Marriott

Remembering the Fillmore East days, Jerry Shirley recalls, “The audiences were great, but they were tough to win over—you certainly had to prove your onions. You had to show them that you knew how to boogie, that you knew how to play very well. And as soon as you did that, they were with you for life.”

A four-minute edit of the Ashford-Simpson-Armstead-penned “I Don’t Need No Doctor,” from the late show on May 28, was issued as a single and made it to #73 in Billboard, but it was FM radio rather than AM that helped make the album a smash. Speaking about the single, released in advance of the album, Marriott told U.K. journalist Richard Green, “It’s the most honest picture we can paint at the moment. It’s not a contrived studio thing, it’s live. If you dig that, you’ll dig the album because that’s the way we are now. We couldn’t stop the audience singing at one point, it was fantastic—several thousand people singing their heads off for one song!”

As detailed in the liner notes to the 2013 Omnivore Recordings boxed set of the complete Fillmore East recordings, the original mixes done by the band were rejected by Anthony because they didn’t include enough of the crowd noise. Eddie Kramer subsequently remixed the multi-tracks, heightening the in-room excitement level to everyone’s satisfaction, and a classic live album was born.

“Four Day Creep,” substantially re-written from Ida Cox’s 1927 recording “’Fore Day Creep,” leads off. A blistering show opener that keeps Marriott in reserve for dramatic effect (“We knew we were going to hear Steve go through the roof with his verse; we were always waiting for that moment,” Frampton later explained), it’s got a lead guitar riff to die for (with Marriott no slouch on second guitar), and lays out the modus operandi for the whole set, i.e., go all-out and have fun doing it. Ridley, Frampton and Marriott can all sing blues-rock with authority, and throughout the album they trade off very effectively.

Marriott whips up the crowd for “I’m Ready” like a country preacher, before Shirley bangs out the ferocious beat and the band enters, with Frampton co-commanding. Again, the group takes a starting point—Muddy Waters’ 1964 recording—and reimagines the music to Willie Dixon’s words. As Frampton described it in the Omnivore box liner notes, “I’ve gone back and listened to the original, and our version is nothing like it. It’s like buying a house for the location, then tearing it down and building it back up from scratch—it looks completely different.” By the four-minute mark, the band is wailing like Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and the Who in a Cuisinart, heavy metal meets the blues.

“Stone Cold Fever,” the original credited to all four members, is driven by Marriott’s razor-blades-in-the-throat vocal and his doubling of Frampton’s main riff, a slower cousin to Jimmy Page’s “Communication Breakdown” theme. Midway through, the band vamps while Marriott improvises a soulful break in the style of his hero Solomon Burke, before another massive guitar riff appears, with Shirley and Ridley pumping alongside, solid and no-frills playing.

At over 23 minutes, “I Walk on Gilded Splinters” (from the last of the four shows) takes up an entire side of the original LP set, and represents Humble Pie’s versatility and ability to play with dramatic dynamics in a psychedelic-adjacent mode. Mac Rebennack (professionally known as Dr. John) featured the spell-casting tune on his Atco label debut in 1968, and it almost immediately became a go-to for acts seeking a skeleton for no-holds-barred improvisation or just a spooky, funky showcase. Johnny Jenkins recorded it with Duane Allman, and Cher did a version too, before Humble Pie added it to their set. Marriott shows off his harmonica skills, Frampton assays a variety of tones and moods, and at the 16-minute mark, Shirley and Ridley begin to give things a decidedly Cream-like bent in support. Whether this represents Humble Pie at their most indulgent you’ll have to decide, but the Fillmore crowd is definitely on their side.

The last three tracks are from May 28’s magnificent second set, although they’re presented out of order. The 15-minute “Rollin’ Stone” fills another LP side; in performance it came between the two Ray Charles-inspired numbers. Marriott screams, moans and testifies about being “strung out” and in a fantastical love affair, and the audience yells back encouragement, taking the whole thing a long, long way from Muddy Waters’ original. No stranger to overindulgence in drink and drugs, Marriott brings the whole force of his over-the-top personality to lead the audience in an almost unhinged call-and-response. As Shirley says in the boxed set liner notes, “We would take it from a roaring lion to a quiet mouse, and it had that great raucous ending, which Greg and I loved playing.” Frampton, referencing Jeff Beck, Carlos Santana, B.B. King and other greats, nonetheless manages to sound like himself too.

A ramshackle but entertaining “Hallelujah I Love Her So,” with all three vocalists enjoying the loose atmosphere, is followed by a slamming “I Don’t Need No Doctor” to finish the album on a high point, even after all the previous peaks. “I don’t need no doctor/’Cause I know what’s ailing me/I’ve been too long away from my baby/I’m coming down with a misery” is the blues-based premise. Ray Charles’ 1966 single is reconfigured and pumped-up majestically. Frampton and Marriott trade solos, and the Shirley/Ridley combo has some of their most potent moments. You can practically feel the sweat dripping off the ceiling and see Marriott prowl the stage as he affirms he’s “had a good time” along with the audience, before Humble Pie hand the exhausted patrons over to Lee Michaels, who might have been quaking at the prospect of following such an onslaught.

On July 8, 1971, Humble Pie opened for Grand Funk Railroad at Shea Stadium—a show that sold out faster than the Beatles’ appearance there—but by the time Performance Rockin’ The Fillmore hit record shops, Frampton had quit, replaced by Clem Clempson for the next successful phase of Humble Pie’s career. There were more gold records, and headlining tours, to come.

For the full, sad tale of Humble Pie’s leader, Simon Spence’s All Or Nothing: The Authorized Story of Steve Marriott is a must-read. Marriott died at the age of 44, perishing in a house fire set by his lit cigarette when he passed out in bed. Frampton of course went on to superstardom with his own live album Frampton Comes Alive in 1976, and is still semi-active. Ridley passed away from complications of pneumonia in 2003; Shirley turned 71 in 2023, always willing to recount his days as part of one of the most rockin’ ensembles ever.

Bonus Video: Watch Humble Pie perform “Rollin’ Stone” live in 1971

Related: 10 great Live at the Fillmore albums

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

2 Comments

One of the best Live albums of the 70’s! Vastly under rated.

I remember my older brother bringing this lp home and playing it whether he was alone or had pals over and it was a staple at every get together, car ride and tape player we heard around town. It certainly dazzled whenever it was on and has truly held up over the years as a great album set to listen to for pretty much any activity you’d like to enjoy a great dose of solid rock music. Great story! Thanks for stirring up the memories this lp brought back!