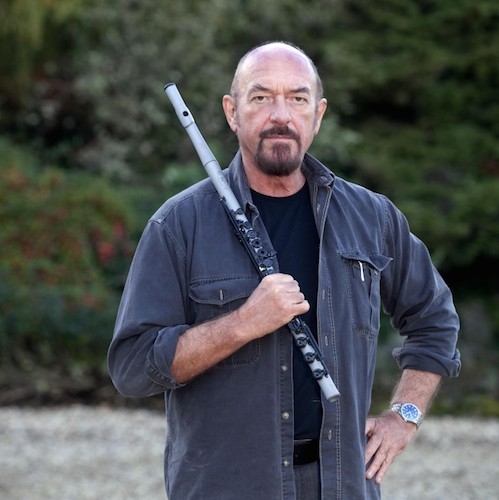

“No way to slow down,” chants Ian Anderson at the close of “Locomotive Breath,” the penultimate song in what was billed as Jethro Tull: The Rock Opera, not, notably, the band. That sentiment was apt for the now-balding, but still spry, flute-slinging, leg-lifting founder of the British rockers named after the 18th century agriculturalist who is also the putative subject of the 20-song, two-act set, combining selections from his catalog with four new songs, which address his ongoing concerns about global warming, GMOs and the future of small farming.

While 130 miles away at Desert Trip, classic rock icons Paul McCartney and Neil Young were entertaining 75,000 fans for “Oldchella,” Anderson and his cohorts—at the ornate, historic Pantages in the heart of Hollywood—with the help of an on-screen narrative (and several “virtual” singers), were wowing a packed house on October 15, 2016, of 2,000 paying upwards of $200 a pop for orchestra seats.

The cognoscenti has not been kind to Anderson nor Tull over the years—not only are they rarely heard as candidates for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction (not surprising, given the nominating committee’s pronounced anti-prog bias), the band’s still excoriated for being awarded the inaugural Grammy for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance in 1988, when Crest of a Knave was inexplicably tapped over the likes of Metallica, AC/DC, Iggy Pop and Jane’s Addiction.

Related: Jethro Tull wins first metal Grammy, 1989

Still, Jethro Tull holds a special place in my own rock narrative—their December 1969 headlining show at the Fillmore East over Fat Mattress (fronted by Jimi Hendrix Experience bassist Noel Redding) and a then-unknown power trio from Flint, Michigan, by the name of Grand Funk Railroad, was my very first rock concert as a high school senior (not counting the Four Seasons swiveling onstage at the Westbury Music Fair). To this day, thousands of shows later, it remains one of the loudest I’ve ever heard.

For a period of four years—from 1969’s breakthrough sophomore album Stand Up, through Benefit, Aqualung, Thick as a Brick, Living in the Past and culminating with 1973’s Passion Play—Jethro Tull emerged not only as one of the most popular rock bands in the world, but also tackled, in a trilogy of “concept” albums, some of Anderson’s pet themes, such as homelessness (Aqualung), England’s class society (Thick as a Brick) and organized religion (Passion Play) with both satirical bite and contrary conservatism. In addition, the band’s place in rock history includes an appearance at the fabled taping of the 1968 Rock and Roll Circus alongside the Stones, John Lennon, Eric Clapton and the Who, with Tony Iommi as their guitarist, no less (take that those who scoff at Tull’s metal bona fides).

These days, like all aging rockers, in his own much-maligned words—“too old to rock ’n’ roll, too young to die”—Ian Anderson, born August 10, 1947, is trying to figure out how best to straddle the line between nostalgia and relevance. His own answer is a multi-media presentation that indulges his love of musical theatre with a way to re-contextualize (and rework lyrically in some cases) his back catalog, including the hits (“Aqualung,” “Songs from the Wood,” “Living in the Past,” “A New Day Yesterday,” “Locomotive Breath”), some more obscure numbers (Songs from the Wood’s “Jack-in-the-Green,” Heavy Horses’ “Weathercock,” Living in the Past’s “Cheap Day Return”) and several new tunes which help push the narrative along.

Watch a medley of songs from the performance

Slyly employing the Jethro Tull brand without using any of its musicians, Anderson’s accompaniment includes guitarist Florian Opahle, whose wah-wah blues riffs (especially the indelible ones that fuel “Aqualung” and “Locomotive Breath”) affirm the new group’s hard rock/metal credentials along with drummer Scott Hammond, keyboardist John O’Hara and bassist David Goodier (the latter two both sporting roles in the movie to which the group plays along).

Anderson has set his song cycle to a cleverly portrayed story of a ticking time bomb warning about climate change and its effect on the world’s food supply, updating the tale of Jethro Tull to the near future, where the title character wrestles with his legacy as a small farmer developing the bio-fueled technology required to create new produce sources. Syncing up to on-screen singing performances by Ryan O’Donnell and Icelandic violinist/vocalist Unnur Birna Bjornsdottir—along with serving as on-screen narrator—Anderson solves the problem of a wavering, if distinctive, singing voice, and gets to show the full range of his flute-playing pyrotechnics, even pulling out the famed, one-legged “Stand” at the conclusion of “Aqualung” and the set-closing Bach homage, “Bouree.”

Related: BCB’s interview with Ian Anderson

Purists may quibble with the approach—my overly critical companion referred to the fresh-faced O’Donnell’s earnest West End crooning as “listening to Harry Potter sing Jethro Tull”—but for the most part the interaction between live and filmed is seamless. At one point, aptly during “Living in the Past,” Anderson indulges in a breathless flute duet with his younger self on-screen, as does guitarist Opahle, without missing a beat, or riff.

And while the message gets a bit muddled, it is clear that Anderson is telling his own story, as much as the fictional Tull, about going against his parents’ wishes and pursuing a life in the arts, and it is also clear that what the crowd has come to hear is his distinctive playing, those trills on flute the equivalent of a guitarist bending blues notes, made aptly clear in the duets between Ian and Opahle on “Back to the Family” and Anderson’s own harp solo in Stand Up’s rousing “A New Day Yesterday.” He latter makes clear what one of the songs played over the PA during intermission suggested: Ian Anderson does for the flute in a rock ’n’ roll context what Little Walter did for the harmonica.

In the end, Jethro Tull: A Rock Opera makes several things clear. Starting out as a blues band before guitarist Mick Abrahams split to form Blodwyn Pig, Anderson and Tull still touch on those early British R&B roots, even as their groundbreaking move to the more earthy, English pastoral tones of Stand Up prefigured everything from Traffic’s John Barleycorn Must Die to the Decemberists, Mumford and Sons and countless others. Based on those influences alone—not to mention two of the most indelible guitar riffs in history in “Aqualung” and “Locomotive Breath”—Jethro Tull deserves to at least be in the discussion for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Even if neither the band, nor its namesake, still exist. For now, though, Ian Anderson keeps this train a-rolling full steam ahead. He’s not “Living in the Past,’ he’s headed for the future.

Watch Ian Anderson perform “Aqualung” in The Rock Opera, Luxembourg, 2016

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up For the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

- Los Lobos: The Wolf is More Than Surviving - 01/29/2022

- Ian Anderson Celebrates The Real Jethro Tull - 08/10/2021

- Has the Golden Age of the Rock Bio/Memoir Already Peaked? - 10/13/2020

2 Comments

Remember going to the successive Jethro Tull concerts at Cobo Hall in Detroit. As with many of the big bands, the concerts back then coincided with the bands new albums. Tull’s concerts always were a very cinematic experience incorporating visual and special effects.

One concert I remember Anderson was in mid song when you heard a phone ring and he crossed to the keyboard where he picked up a phone receiver and talked (no cell phones back then) it was all a part of the stage play. Concerts were much more fun in the 60’s, 70’s and early ‘80’s, then everything changed!

Jethro Tull’s multi-genre contributions to “Rock” music’s catalogue are undeniable. It’s a waste of breath to continue complaining about the band’s omission to the HOF, as that organization is an obvious joke, and shown itself to be, sadly, but undeniably worthless. That said, as much of a fan as I am of Tull, which makes one automatically a fan of Ian Anderson, I feel a lot of ambivalence about Anderson, for as much of a true musical genius as he is, and as much as his creative music has also become part of my DNA, I have strong feelings about the way he’s summarily cast past members of Jethro Tull aside, against their wishes, especially Martin Barre, who’s been a loyal and essential foil to Anderson, as well as the band’s beating heart, as his whole life’s work. Articles about Anderson dating from the beginning of the band have clearly painted Anderson as a control freak. And as long as Tull’s band members could handle it, one had to write off this aspect of Anderson as a not so pleasant part of his genius, as well as a bottom line reason why Jethro Tull was so compellingly tight as a live band. But in that same breath, something should be said for the incredible musicality the members of Jethro Tull have given in (one would have to assume) unquestioning loyalty to Anderson over the years, only to be cast aside when the puppeteer decided that he wanted new blood. All that aside, this broadway type stage production looks astounding.