In 1978, Ian Hunter, the former Mott the Hoople frontman, was living in New York City, licking his wounds after the critical and commercial drubbing his last two albums had taken: All American Alien Boy had stalled at #177 on the Billboard album chart, and his American label Columbia refused to even release the Roy Thomas Baker-produced followup Overnight Angels, which sold decently in Australia and nowhere else (Hunter himself later called it “a mistake”).

In 1978, Ian Hunter, the former Mott the Hoople frontman, was living in New York City, licking his wounds after the critical and commercial drubbing his last two albums had taken: All American Alien Boy had stalled at #177 on the Billboard album chart, and his American label Columbia refused to even release the Roy Thomas Baker-produced followup Overnight Angels, which sold decently in Australia and nowhere else (Hunter himself later called it “a mistake”).

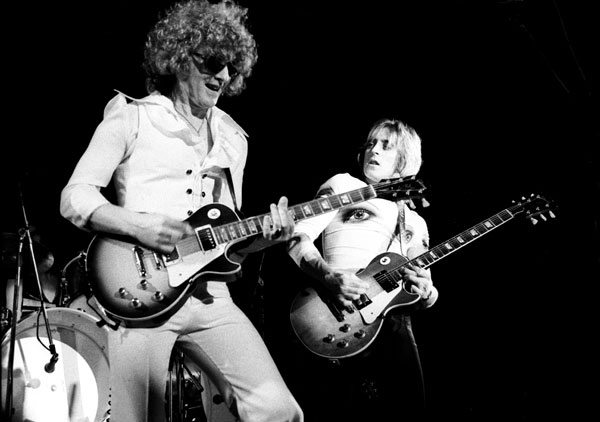

His first solo album, Ian Hunter, a collaboration with guitarist Mick Ronson, had launched his post-Mott career in high style in 1975 and he’d failed to follow up that success. As he told journalist Kris Needs about his 1978 crisis, “I was real scared because I hadn’t got any material. That’s my only weapon, so to speak, so there’s no point in running around fucking record companies because if I got a deal I couldn’t do anything. So I thought, there’s two things I wanted to do—get better on piano, for some strange reason, and then I wanted to write songs. So that’s what I did. The only thing that ever stops me going nuts is writing a song. It’s kind of my therapy.”

Hunter and Ronson had tried to form new musical partnerships with Felix Pappalardi and Corky Laing from the band Mountain, and jammed with ex-Velvet Underground member John Cale, without either getting out of the workshop stage. Then Hunter became aware that unlike many ’70s stars, he wasn’t being excoriated or called a “dinosaur” by the punk rockers who’d taken over the charts in his native U.K., but in fact was being cited as a positive influence by the Clash, Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks and others. Hooking up with original Sex Pistols bassist Glen Matlock, Hunter recorded some developing songs with him, including “Bastard,” “Wild East” and “Standing In My Light,” at the punk-friendly Wessex Sound studios in London. (The drummer was Clive Bunker, formerly of Jethro Tull, who was now playing sessions with the likes of Generation X.)

When that configuration also didn’t work out, Hunter grabbed an opportunity proffered by his manager to start over in New York City, where three E Street Band members (pianist Roy Bittan, drummer Max Weinberg and bassist Gary Tallent) were available. Hunter now had a fistful of fresh songs, Chrysalis Records as a new home, the Boss’ rhythm section, and Ronson as enthusiastic sidekick once again.

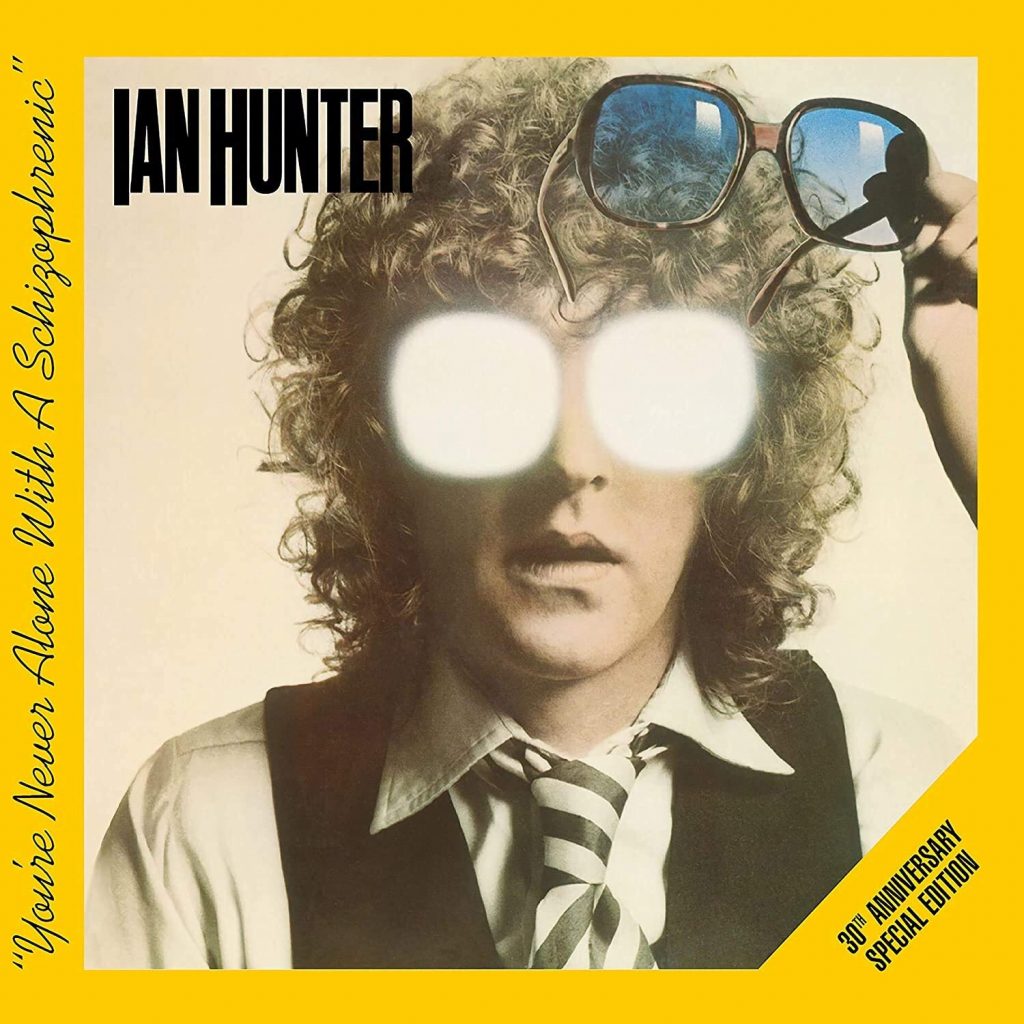

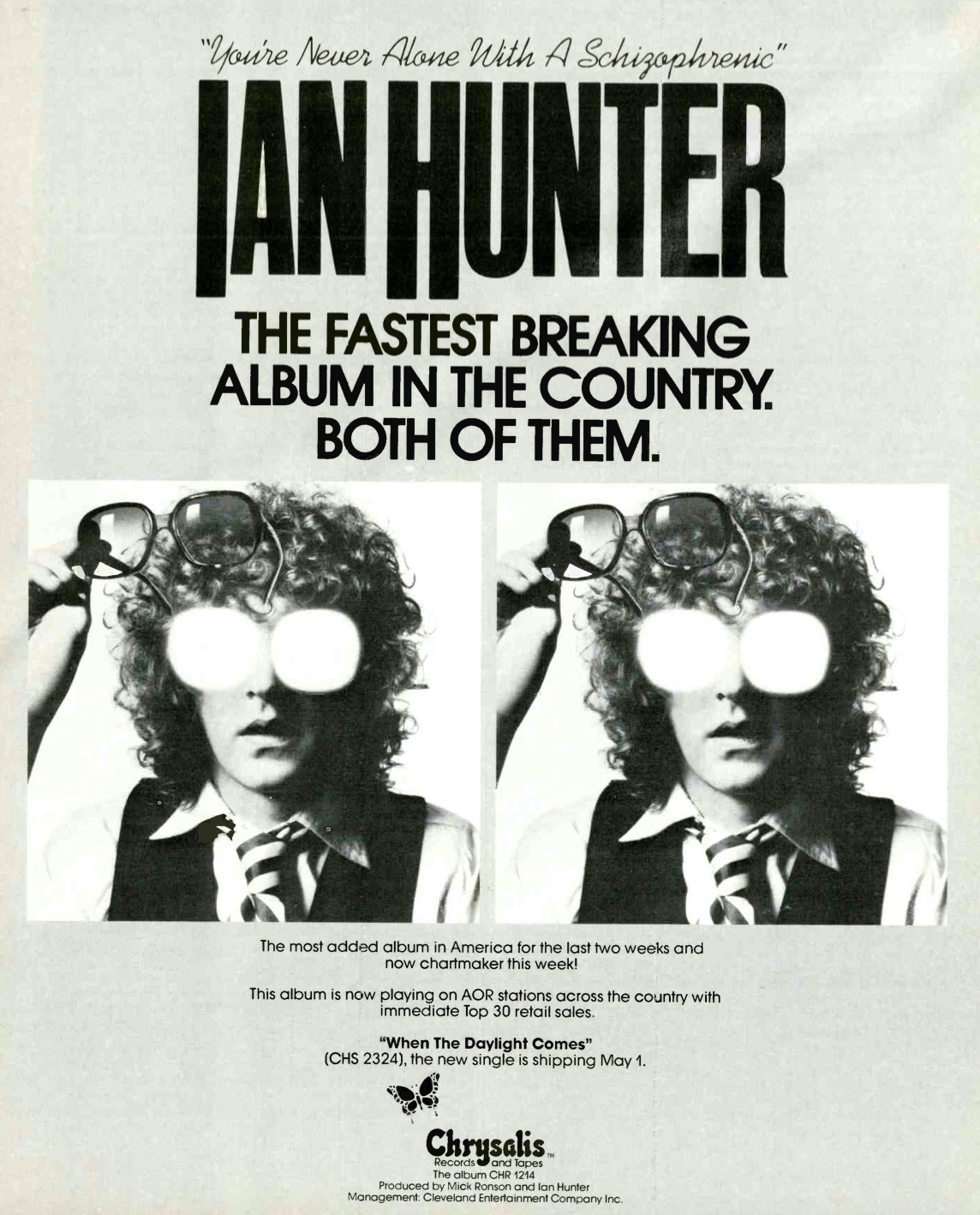

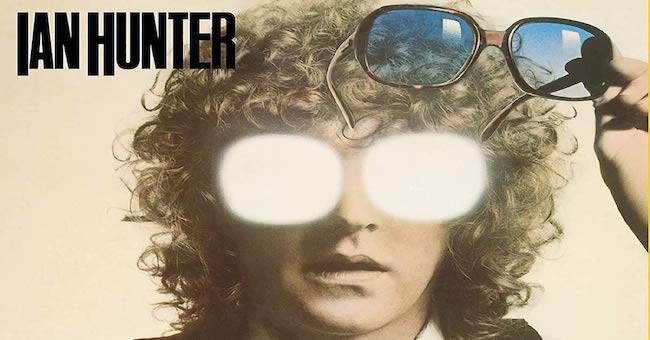

In the winter of 1978-79, sessions for an album tentatively titled The Outsider got underway at the Power Station in Manhattan, with engineer Bob Clearmountain. This time, Hunter and company delivered the goods; by the time it was released in 1979 the album title replicated a public bathroom scrawl Ronson spotted, You’re Never Alone With a Schizophrenic. It was medically inaccurate (for starters, schizophrenics don’t have multiple personality disorder), but as a don’t-take-this-too-seriously rock ’n’ roll title, it was perfect.

The LP begins with “Just Another Night,” which in a perfect world would have done better than #68 on Billboard’s Hot 100 when released as a single. The lyrics humorously tell the tale of Hunter’s stay in an Indianapolis jail cell during Mott the Hoople’s 1973 tour: “All the reefer madness put a poor kid in jail.” (Hunter’s book about life on the road, Diary of a Rock ‘N’ Roll Star, was published in June 1974 and is highly recommended.) A driving rocker that shows Hunter’s devotion to Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and the Rolling Stones, “Just Another Night” showcases the E Street guys, and background vocals from Ellen Foley, Rory Dodd and Blue Öyster Cult’s Eric Bloom to echo Hunter’s shouts.

“Wild East” is another tongue-in-cheek complaint, but in a more abstract vein: “Now some cynic from the methadone clinic/He keeps bothering me/He writes all my lyrics backwards on diapers/And hangs them from the local trees.” Saxophonists George Young (tenor) and Lew Delgatto (baritone), who’d worked in organist Jimmy McGriff’s band, wail along with a track that contains some doo-wop whispers and synthetic percussion. Like just about every track on the album, each sonic nook and cranny is filled with activity in a dense “wall of sound”—nothing “subtle” on display here.

“Cleveland Rocks” begins with the voice of disc jockey “Moondog” Alan Freed and a beeping synthesizer before Ronson’s slashing chords, multiple pumping keyboards, Weinberg’s masterful smashing and Hunter’s enthusiastic, aggressive vocal take center stage. Eventually Ronson—or Hunter?—lays down some piercing single notes as the track builds further into a joyful noise. Hunter, who’d previously recorded the song as “England Rocks,” told his biographer Campbell Devine that he always had a soft spot for the American Midwest industrial towns that supported Mott the Hoople: “People used to make fun of Cleveland, it was ‘uncool.’ I didn’t see it that way. There’s a lot of heart in Cleveland.” The song became more famous when it was recorded by Seattle band the Presidents Of The United States of America and used as the theme for the popular sitcom The Drew Carey Show.

Related: A cover of “Cleveland Rocks” was used for a popular TV sitcom

The ballad “Ships” is a lament centered around Hunter’s relationship to his father: “It seems you and I are like strangers a wide ways apart/As we drift on through time.” Hunter had to be encouraged to finish the song, which had been around for five years and depends too much on the tired cliché “ships passing in the night.” Despite the song’s flaws, he gives it a committed performance, and hits some impressive high notes, surrounded by a celestial chorus, a synthesizer approximating a harp, and other frills. Hunter was pleasantly surprised when Barry Manilow took his own version of “Ships” to #9 in Billboard in 1979.

Ronson sings much of the final track on side one, “When the Daylight Comes.” According to Hunter, Ronson was partial to the tune while Hunter himself never really liked it, thinking he’d aimed for a commercial hit too obviously. Hunter was having a chat with a visiting Bruce Springsteen when it was time to record the vocal, and telling Ronson he was busy, dared Ronson to do it himself if he was so keen on it. Eventually, Hunter did add his own vocal part, but the recording remains a bit of a damp squib.

“Life After Death” is another piano-driven, straight-ahead rocker, and launches the second LP side with a solid winner. Hunter wonders about reincarnation, and whether another shot at living from a different starting point would be interesting: “Do you stop, take another roller coaster ride/Do I beg, steal, cheat or lie?” In a torrent of words he lays out one of his funniest couplets, “Is it any wonder, I feel just a bit under/I hear choirs filled with Fenders say return to sender.” The last minute is a careening mash-up of interesting ideas, with prog-rock touches in the arrangement and vocal.

Listen to a live version performed a few months after the album was released

The next three songs are generally regarded as among Hunter’s best, and the heart of the album, but they are all slower and more dependent on mood. As Hunter told Needs, he had more range as a songwriter than he was given credit for: “I’ve always had this problem where I was considered a rocker, as the frontman with a rock band. I never considered myself that way. I always considered myself a singer-songwriter, even when I was with Mott. I always used to have grave difficulty saying ‘we’; it was always ‘me.’”

“Standing In My Light” is a thinly veiled attack on the former Ronson, Hunter and David Bowie manager Tony DeFries. “I’ve always had a hard time with managers,” Hunter told Campbell Devine. “They want consistency and money. I think consistency is boring and my money should be mine. Never the twain shall meet!” The lyrics attempt some sort of reconciliation amid the kiss-off at the end: “I wish you luck on your very last chance/Because I know you blew it at the song and dance/You froze my feelings but that’s alright/And you’re standing in my light.” That Hunter constructed such a sumptuous, soaring melody for the song is a small miracle, given how much anger he was holding.

Hunter describes “Bastard” as “a true love song…it never runs smooth. It’s a truthful love song as opposed to all the dreck.” The longest track on the LP, it benefits from razor-like guitars, ferocious bass and drums from Tallent and Weinberg, and multiple keyboards from Bittan and guest John Cale on piano and ARP synthesizer. Hunter spits out the words, excoriating a woman in terms that show the distance between 1978 and 2021 standards: “You twist me ’til I’m lame, then you spin the coin again/You’re such a bastard/You’re so naturally perverse, you ain’t even gotta rehearse/You’re such a bastard/Fly like a witch, without running in some pitch/Why don’t you break the switch that takes me over.”

“The Outsider,” an epic, cinematic, country-flavored tune that isn’t far from Springsteen, Ennio Morricone or the Dylan of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” finishes the album with a flourish. At 4:00, Ronson lays down some of his most impressive guitar work. The lyrics are evocative and dead serious: “Just killed a man in a town called Nightfall/Damned if I can remember it all/My hand it was shaking but his talk it was tall/I paid for the funeral crew/And it seems like I’ll never reach Mexico/They’re heading me off every place that I go.”

Released on March 27, 1979, You’re Never Alone With a Schizophrenic rose to #35 on the Billboard album list during the 24 weeks it charted, and got significant airplay on FM radio. “Schizophrenic was the best solo album I ever did but was panned by the English rock critics because I was a U.S. resident—very small minded,” recalled Hunter when the album was reissued as an expanded double-CD in 2009. “The only problem was that it didn’t have a hit single!”

The Hunter-Ronson tour did good business, and the team produced sessions for Ellen Foley, David Werner and Genya Ravan during this period as well. Ronson succumbed to liver cancer in 1993 at the age of 46, shortly after rejoining Hunter for the YUI Orta album, credited as the Hunter Ronson Band, and producing Morrissey’s Your Arsenal.

Ian Hunter is still very much alive and kicking, issuing excellent albums and touring, doing a series of Mott the Hoople reunion shows in 2013, celebrating his 80th birthday with his Rant Band during a four-night stand at City Winery in New York in 2019, and helping Def Leppard celebrate their Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction that year too, playing “All the Young Dudes.”

Related: Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott on Ian Hunter

The Covid pandemic and a case of tinnitus have kept him off the road recently, but he’s made it clear quitting is not on his mind: “I always had this fantasy about being a Jerry Lee Lewis when I got older. It’s a circle, it keeps on going, but you got to be careful what you do. You’ve got to deliver now and again, otherwise that’s all you’ve got. Then you’re fucked!”

Bonus Video: Listen to a live version of “Cleveland Rocks” from 1979

Hunter’s recordings including Schizophrenic and his two most recent albums, featuring an all-star cast, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

7 Comments

Thank you, Ian! And thanks for this excellent article, Mark!

Good article on two very underrated musicians (Ian Hunter and Mick Ronson).

Killer album I loved in high school. Saw him open for Kinks in Detroit on that tour. Dirty Laundry from early 90s also brilliant!

I was there too! Really went to see Ian/Mick but The Kinks were great too!

I bought this album at a Revco drug store in Marion, Indiana in the fall of ’81 for .25 cents. This was my first exposure to Ian. I fell in love with the first play. I then bought everything I could find by Ian or Mott–wonderful songs, wonderful memories.

Always in the first few rows during the MTH and solo tours in either Boston or Cleveland. Hunter personified the disgruntled rock star. Meeting the demands of touring with consistently good shows. Taking the creative endeavor of the songsmith and reproducing the electro-mechanical process with success in front of his adoring fans. Just like any artist he had his highs and lows creatively. Many tunes have withstood the test of time. He certainly didn’t help his career by alienating the people associated with him in the biz. But that is part of his legitimacy. Still out there on the road when he can be with his wife Trudi at his side. Mr. Hunter (Patterson) is an enduring and endearing artist that has made his mark in the R&R genre of music.

And I just heard a new song on Sirius/XM’s Deep Tracks a couple of weeks ago that was credited to Ian, Brian May, and Joe Elliott of Def Leppard. And Ian still sounds pretty good.